Published online Nov 27, 2024. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v16.i11.3584

Revised: September 5, 2024

Accepted: September 25, 2024

Published online: November 27, 2024

Processing time: 190 Days and 0 Hours

Blue rubber blister nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a congenital, rare disease characterized by venous malformations of the skin and internal organs, affecting all systems throughout the body. The pathogenesis is unknown. There is no con

An 18-year-old man with early onset of BRBNS in early childhood is reported. He presented with recurrent melena and underwent malformed phlebectomy and partial jejunectomy and ileal resection. The patient had melena before and after surgery. After active treatment, the patient's gastrointestinal bleeding improved. This was a case of atypical BRBNS with severe gastrointestinal bleeding and severe joint fusion, which should be differentiated from other serious joint lesions and provide clinicians with better understanding of this rare disease.

This case of critical BRBNS with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, DIC and severe joint fusion provides further understanding of this rare disease.

Core Tip: Blue rubber blister nevus syndrome is a rare disease. The mechanism of the disease is not fully understood. Lack of awareness among clinicians leads to delays in diagnosis and treatment. This severe case had a long course of illness and difficult diagnosis and treatment. The patient was treated with surgery because the gastrointestinal bleeding did not resolve after medication, repeated intervention and other treatments. The patient had severe joint fusion and was unable to walk, which seriously affected his quality of life. Clinicians should pay attention to the differential diagnosis of rare diseases while learning about them, so as to avoid misdiagnosis and missed diagnosis.

- Citation: Wang WJ, Chen PL, Shao HZ. Blue rubber blister nevus syndrome: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2024; 16(11): 3584-3589

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v16/i11/3584.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v16.i11.3584

Blue rubber blister nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a disease characterized by multiple widespread venous malformations. The most common symptom is venous malformations of the skin and internal organs. Cutaneous angiomas are bluish or purple, soft, rubbery, nipple-like nodules with wrinkled and hyperhidrotic surfaces[1]. Cutaneous angiomas are usually diagnosed in infancy or childhood, with only 4% of reported cases diagnosed in adulthood. After the skin, the gas

An 18-year-old man was admitted to the hemangioma department with the main complaint of multiple blue-purple cutaneous nevus for 18 years, intermittent melena for 4 years and repeat black stools for 2 weeks.

The patient was born with multiple blue angiomas on the buttocks and back, which gradually enlarged with age, covering the chest, back and limbs. These angiomas were bluish or purple, soft, rubbery, nipple-like nodules and were not treated. Eight years ago, the patient often felt pain when walking. However, no treatment was given because there were no positive signs such as fractures. Six years ago, he could not straighten his legs or even get out of bed and went to several hospitals without a clear diagnosis. Four years ago, the patient started developing blood in his stools, and underwent genetic testing in Shanghai East Hospital, which revealed the TEK gene mutation. BRBNS was confirmed. He was given hemostatic drugs, blood transfusion, oral sirolimus treatment, and injected with absolute ethanol > 10 times for cutaneous angiomas. Two weeks ago, he was admitted to the above hospital due to recurrent melena. Capsule endoscopy showed multiple jejunal venous malformations and active bleeding. The patient was given hemostatic drug application, blood transfusion and oral sirolimus again. However, the gastrointestinal bleeding did not stop and he was transferred to our hospital.

The patient had impaired joint mobility for 6 years and took sirolimus irregularly for 4 years. He was injected with absolute ethanol > 10 times for cutaneous angiomas 4 years ago and underwent capsule endoscopy 2 week ago.

The patient denied any family history of cutaneous angiomas or gastrointestinal bleeding.

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: (1) On admission: Body temperature, 36.3 °C; blood pressure, 110/70 mmHg; heart rate, 80 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 19 breaths/minute; and (2) On admission to the intensive care unit (ICU): Body temperature, 36.8 °C; blood pressure, 137/81 mmHg (plasma and cryoprecipitate were transfused daily before the ICU); heart rate, 75 beats/minute; respiratory rate, 15 breaths/minute. The patient had multiple blue-purple, cutaneous nevi all over the body (Figure 1). The left upper limb was hypertrophic, deformed with palpable phleboliths under the skin (Figure 1A). The left elbow and bilateral knee joints had limited extension (Figure 1A and B). The maximum extension of the left elbow and both knee joints was 60°and 160°, respectively. The patient was not able to walk.

Table 1 shows coagulation parameters at the time of admission, during hospitalization, and at discharge.

| Hb (110-160 g/L) | Plt (100-300 109/L) | FBG (1.8-3.5 g/L) | FDP (0-5 g/mL) | DD (0-0.55 g/mL) | APTT (22-35 seconds) | PT (9-14 seconds) | TT (14-21 seconds) | |

| At admission | 58 | 114 | 0.52 | 222.03 | 69.12 | 30.6 | 16.2 | 26.4 |

| H/L | 38 | 48 | 1.08 | 506.16 | 144.50 | 23.3 | 13.0 | 18.0 |

| At discharge | 41 | 52 | 1.08 | 188.40 | 66.54 | 31.4 | 13.0 | 18.0 |

Capsule endoscopy at the other hospital revealed multiple venous malformations and active small intestinal bleeding (Supplementary Figure 1).

The patient's previous peripheral blood gene test showed a missense mutation in the TEK gene on chromosome 9, with a mutation site NM_000459: Exon17: C.C2740T: p.Leu914Phe, and a variation of 0.62%.

(1) BRBNS; (2) Gastrointestinal bleeding; (3) Severe anemia; and (4) Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

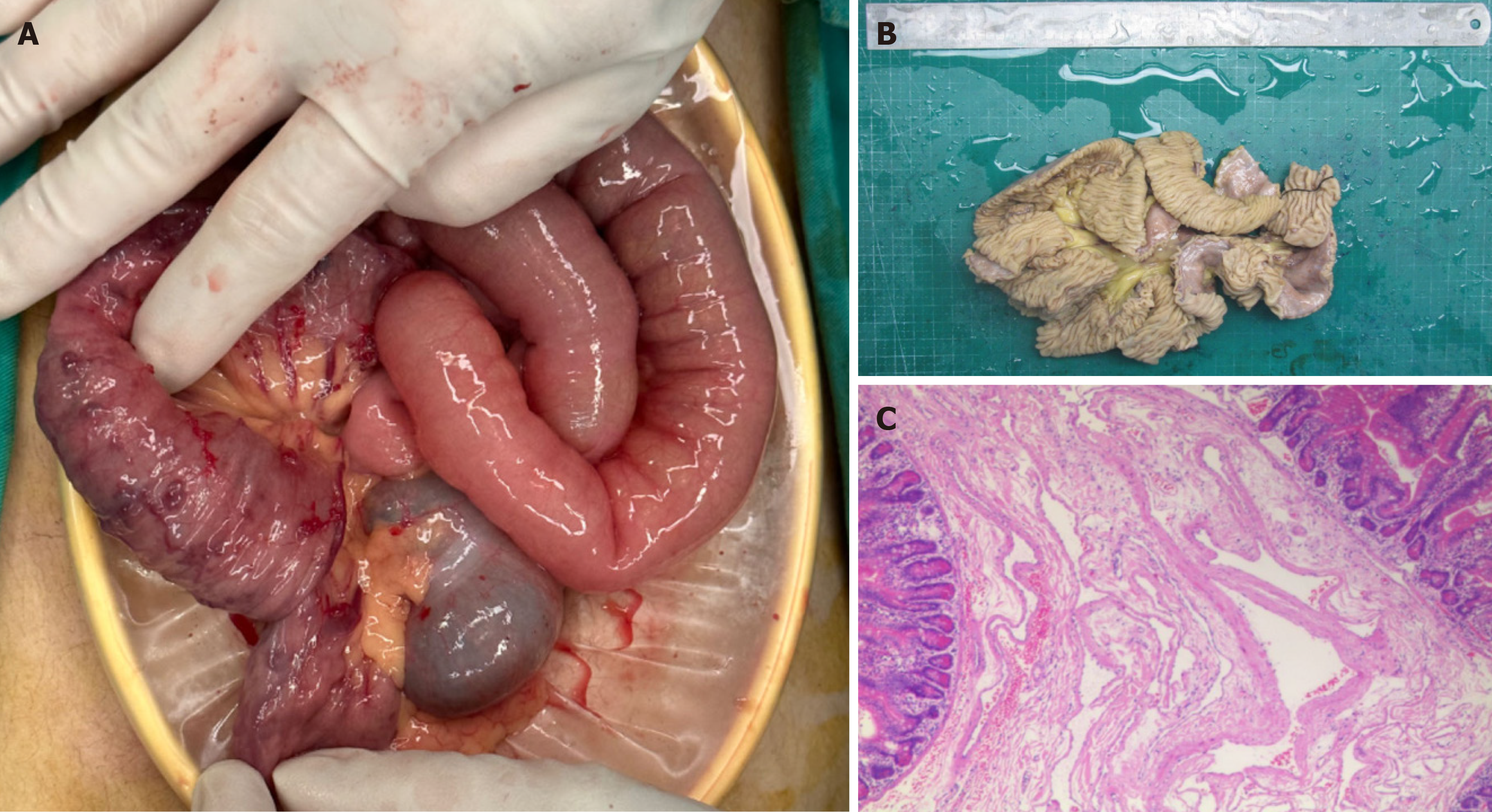

Capsule endoscopy revealed multiple venous malformations and active bleeding in the small intestine (Supplementary Figure 1). The patient was recommended for gastrointestinal surgery due to active bleeding, low fibrinogen level, high risk of bleeding during bowel preparation, and potential gastrointestinal perforation due to endoscopic venous he

From day 2 to 4 in the ICU, 2-5 L/day of bloody stools were released. In addition to component blood transfusion, the patient was given thrombin 2 U/day before surgery, which was boosted to 6 U/day after admission to the ICU, along with vitamin K 10 mg twice daily, tranexamic acid 0.5 g once daily, and fibrinogen concentrate 4-8 g daily. During the patient's 17-day hospital stay, the patient was given almost daily transfusions of red blood cells and cryoprecipitate. Hemoglobin, fibrinogen and fibrinogen degradation products fluctuated at 38-70 g/L, 0.30-1.08 g/L, and 129.77-506.16 mg/mL, respectively (Table 1).

The drainage fluid of the abdominal drainage tube changed from bloody to pale yellow on day 3 in the ICU (post

This patient developed in infancy systemic cutaneous nevi as the first manifestation, and then movement disorders, joint fusion and severe gastrointestinal bleeding. The patient's condition did not alleviate significantly after oral treatment with several drugs and anhydrous ethanol injections. This was a critical case of BRBNS with life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding and joint fusion different from previously reported cases.

BRBNS is characterized by multiple blue-purple nodules or masses on the skin and gastrointestinal tract, and can affect different organs. The lungs, bronchi, urinary tract, brain, liver, spleen or heart can be involved. Gastrointestinal bleeding[6] leads to hematemesis, melena, iron deficiency anemia, and even life-threatening hemorrhagic shock. Small bowel lesions[7] can lead to intussusception and intestinal obstruction, brain lesions[8] can lead to cerebral infarction, vertebral lesions can lead to spinal cord compression, and bronchial lesions[9] can lead to chronic cough. This patient mainly presented with gastrointestinal symptoms such as bleeding and movement disorder due to joint fusion. Clinical differential diagnosis with familial hemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler Weber-Rendu disease), angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry’s disease), dyschondroplasia with hemangiomas (Maffucci’s syndrome), multiple glomangiomas and Kaposi’s sarcoma may be difficult[1]. In particular, this case should be distinguished from Maffucci's syndrome, which is a clinical syndrome with a tendency to malignant transformation due to somatic mutations leading to mesodermal dysplasia, mainly characterized by multiple chondroma and hemangioma[10]. Maffucci's syndrome has mostly bilateral invol

The patient had the typical skin and gastrointestinal lesions of BRBNS, a positive gene report and no family history. During the long medical treatment, the patient was given sirolimus tablets orally, and the systemic nodular lesions and gastrointestinal bleeding were not in remission. Gastrointestinal bleeding and severe anemia persisted after oral hemostatic drugs, repeated transfusions of blood products and cutaneous vascular embolization. The patient had severe hypofibrinogenemia at admission. Despite the administration of a large number of blood components (red blood cells, plasma, and cryoprecipitate) before and during surgery, the patient still had severe gastrointestinal bleeding after surgery, which may be related to secondary DIC induced by combination of primary disease and surgery. Anastomotic hemorrhage cannot be completely ruled out, because the patient refused CT scanning. However, combined with the complete resection of the vascular lesions, and clear abdominal drainage, we considered anastomotic bleeding to be unlikely. After positive treatment with hemostatic drugs, antifibrinolytic drugs, massive red blood cell transfusions to alleviate anemia, cryoprecipitate (24 U/day) and plasma to replenish coagulation factors, and target oriented transfusion of fibrinogen concentrate (4-8 g/day), the bleeding was significantly reduced. Thromboelastography showed that there was no abnormality in the activity of coagulation factors at admission and discharge. Coagulation dysfunction was mainly caused by severe fibrinogen deficiency. Careful perioperative management and close monitoring are necessary when the coagulopathy caused by the primary disease increases the risk of perioperative bleeding, but nonsurgical treatment cannot stop the bleeding.

It is important to note that this case differs from previous ones. Firstly, the patient had severe joint fusion of the left elbow and both knees, which was not seen previously. Secondly, extraintestinal vascular lesions differed from previously reported BRBNS with a single, clumpy dilated irregular vascular lumen. In this case, the lesion involved the whole thickness of the intestinal wall from the mucosal to the serosal layer, and the venous malformation was not a solitary, isolated hemangioma. Thirdly, the patient's previous oral administration of sirolimus and iron did not alleviate bleeding and anemia. All the above indicate that this may be an atypical case of BRBNS, or that there were comorbidities that we have not yet identified. Although the gastrointestinal bleeding of the patient was temporarily stopped, joint fusion persisted, and long-term prognosis and quality of life were poor.

We report a case of critical BRBNS with gastrointestinal hemorrhage, DIC and severe joint fusion, which provides clinicians with further understanding of this rare disease.

We would like to thank Shanghai Dongfang Hospital for providing the gastroscopy report of the patient.

| 1. | Palleschi GM, Torchia D, Fabbri P. Blue rubber-bleb nevus syndrome: report of a case associated with osteoid osteomas. J Dermatol. 2005;32:589-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kozai L, Nishimura Y. Clinical characteristics of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome in adults: systematic scoping review. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:1108-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rimondi A, Sorge A, Murino A, Nandi N, Scaramella L, Vecchi M, Tontini GE, Elli L. Treatment options for gastrointestinal bleeding blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: Systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2024;36:162-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Laube R, Rickard M, Lee AU. Gastrointestinal: Small intestinal blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36:2637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Soblet J, Kangas J, Nätynki M, Mendola A, Helaers R, Uebelhoer M, Kaakinen M, Cordisco M, Dompmartin A, Enjolras O, Holden S, Irvine AD, Kangesu L, Léauté-Labrèze C, Lanoel A, Lokmic Z, Maas S, McAleer MA, Penington A, Rieu P, Syed S, van der Vleuten C, Watson R, Fishman SJ, Mulliken JB, Eklund L, Limaye N, Boon LM, Vikkula M. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus (BRBN) Syndrome Is Caused by Somatic TEK (TIE2) Mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:207-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dwivedi M, Misra SP. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome causing upper GI hemorrhage: a novel management approach and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:943-946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jin XL, Wang ZH, Xiao XB, Huang LS, Zhao XY. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:17254-17259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park CO, Park J, Chung KY. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome with central nervous system involvement. J Dermatol. 2006;33:649-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gilbey LK, Girod CE. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: endobronchial involvement presenting as chronic cough. Chest. 2003;124:760-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | El Abiad JM, Robbins SM, Cohen B, Levin AS, Valle DL, Morris CD, de Macena Sobreira NL. Natural history of Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome: Patient survey and review of clinical literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182:1093-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cai Y, Wang R, Chen XM, Zhao YF, Sun ZJ, Zhao JH. Maffucci syndrome with the spindle cell hemangiomas in the mucosa of the lower lip: a rare case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2013;40:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hakim S, Desai T, Cappell MS. Esophageal hemangiomatosis with chest CT revealing a fine, curvilinear, calcified thrombus within the esophagus simulating acute esophageal fishbone impaction: first reported endoscopic photograph of GI manifestations in Maffucci syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1293-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |