Published online Aug 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1751

Peer-review started: February 16, 2023

First decision: April 27, 2023

Revised: May 22, 2023

Accepted: June 13, 2023

Article in press: June 13, 2023

Published online: August 27, 2023

Processing time: 189 Days and 23.1 Hours

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is typically treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). However, recurrence may occur after ESD, requiring survei

To examine the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of EGC survivors following ESD regarding gastric cancer recurrence.

This cross-sectional study was conducted between June 1, 2022 and October 1, 2022 in Zhejiang, China. A total of 400 EGC survivors who underwent ESD at the Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine participated in this study. A self-administered questionnaire was developed to assess KAP monitoring gastric cancer after ESD.

The average scores for KAP were 3.34, 23.76, and 5.75 out of 5, 30, and 11, respectively. Pearson correlation analysis revealed positive and significant correlations between knowledge and attitude, knowledge and practice, and attitude and practice (r = 0.405, 0.511, and 0.458, respectively; all P < 0.001). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that knowledge, attitude, 13-24 mo since the last ESD (vs ≤ 12 mo since the last ESD), and ≥ 25 mo since the last ESD (vs ≤ 12 mo since the last ESD) were independent predictors of proactive practice (odds ratio = 1.916, 1.253, 3.296, and 5.768, respectively, all P < 0.0001).

EGC survivors showed inadequate knowledge, positive attitude, and poor practices in monitoring recurrences after ESD. Adequate knowledge, positive attitude, and a longer time since the last ESD were associated with practice.

Core Tip: This is the first study to examine the knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding monitoring of gastric cancer recurrence after endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). Participants’ average knowledge, attitude, and practice scores indicated inadequate knowledge, good attitude, and poor practice. Significant and positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitude, knowledge and practice, and attitude and practice. Sufficient knowledge, a positive attitude, and at least 12 mo since the last ESD were independent predictors for correct practice. The lack of knowledge and insufficient practice in monitoring cancer recurrence may explain the 89.2% of pathologically confirmed early tumors after ESD.

- Citation: Yang XY, Wang C, Hong YP, Zhu TT, Qian LJ, Hu YB, Teng LH, Ding J. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of monitoring early gastric cancer after endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(8): 1751-1760

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i8/1751.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i8.1751

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer deaths globally[1]. In China, gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with more than 500000 new cases expected in 2022[2]. Early gastric cancer (EGC) refers to cancers located in the mucosa or submucosa of the stomach regardless of local lymph node metastasis, with a better prognosis than advanced gastric cancer[3].

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is considered the first-line treatment for EGC regardless of its size or ulceration[4]. When compared to gastrectomy, ESD provides faster recovery, lower costs, and superior quality of life for patients with EGC. However, non-curative resection can occur after ESD and is strongly associated with the incidence of local recurrence resulting from incomplete resection, undifferentiated histology, a tumor-positive resection margin, lymphovascular invasion, or a depth of invasion greater than one-third of the submucosa[5]. In the 5 years following ESD, there is a cumulative incidence of 11.9% of local recurrences[6]. EGC survivors following ESD have a higher recurrence rate compared with those following gastrectomy[7]. A clinical application of the expanded criteria for ESD further increases the local recurrence rate of EGC[8,9]. Since early detection of recurrence improves survival for patients with gastric cancer[10,11], monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer after ESD is essential in patients as part of a surveillance strategy. However, little is known if patients understand the importance and how to monitor the recurrence of gastric cancer after ESD.

This is the first study to assess knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) regarding monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer among EGC survivors after ESD in Zhejiang, China. We evaluated the KAP related to gastric cancer recurrence, reexamination, and follow-up. Furthermore, we examined sociodemographic factors associated with the practice of monitoring gastric cancer recurrence. The results may help medical practitioners improve the KAP of patients with EGC after ESD and facilitate early detection of gastric cancer recurrence.

This cross-sectional study survey was conducted at the Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine between June 1, 2022 and October 1, 2022. The design phase started in June, focusing on feasibility and ethical considerations. Participants were recruited in July. Data collection and questionnaire surveys began in August. We conducted individual follow-ups and communicated with patients via phone calls. A total of 400 EGC survivors following ESD were recruited by phone. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jinhua Hospital [Approval No. (2022) Lunshendi (211)]. All participants provided informed consent. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients underwent ESD for EGC at Jinhua Hospital; (2) Pathology after ESD revealed high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia, intramucosal carcinoma, or submucosal invasion < 500 µm; and (3) Participants were willing to take part in this study. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients were unable to complete the questionnaire survey due to their inability to write or psychological diseases; and (2) Patients who underwent further gastric surgery.

The questionnaire was self-designed based on previous studies[12,13] and contained 40 questions in four categories in Chinese, including personal information (18 questions), knowledge (5 questions), attitude (6 questions), and practice (11 questions). The knowledge category scored 0-5 points, with 1 point awarded for each correct answer and 0 points for each wrong or unclear answer. The attitude category scored 6-30 points, with 5 points for a positive attitude and 1 point for a negative attitude. The practice category scores ranged from 0-11. Answers of “yes” were given 1 point, whereas answers of “no” were given 0 points. Cronbach’s α of the questionnaire was 0.841. Patients were recruited by telephone calls from the hospital. Patients who agreed to participate in this study were surveyed when they came to the hospital for follow-up. After the questionnaire survey was completed, investigators assessed the completeness, internal continuity, and rationality of the questionnaire. In cases where the questionnaire was incomplete, we contacted the patient by phone and, if necessary, assisted their family in answering it. Twenty-five patients did not come for follow-up. A cut-off point of at least 70% was used to categorize good knowledge, positive attitude, and good practice[14].

Due to the lack of relevant literature, the sample size was calculated based on an anticipated proportion of 50% of ECG survivors engaging in monitoring EGC, with a 95% confidence level and a 5% margin of error[15,16]. As a result, we determined that a sample size of 384 was required.

Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If conforming to the normal distribution, they were expressed as mean ± SD and compared between two groups using the Student’s t-test. If not conforming to the normal distribution, they were expressed as medians (ranges) and compared between two groups using the Mann-Whitney U-test. As for continuous variables among three or more groups, they were compared using the analysis of variance (a normal distribution with equal variance) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (skew distribution or unequal variance). Correlations were tested using Spearman’s test. Categorical variables were expressed as n (%). The influencing factors of proactive practice (categorized according to at least 70%) were explored using multivariate logistic regression. Variables with P < 0.05 were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Two-sided P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The data were analyzed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

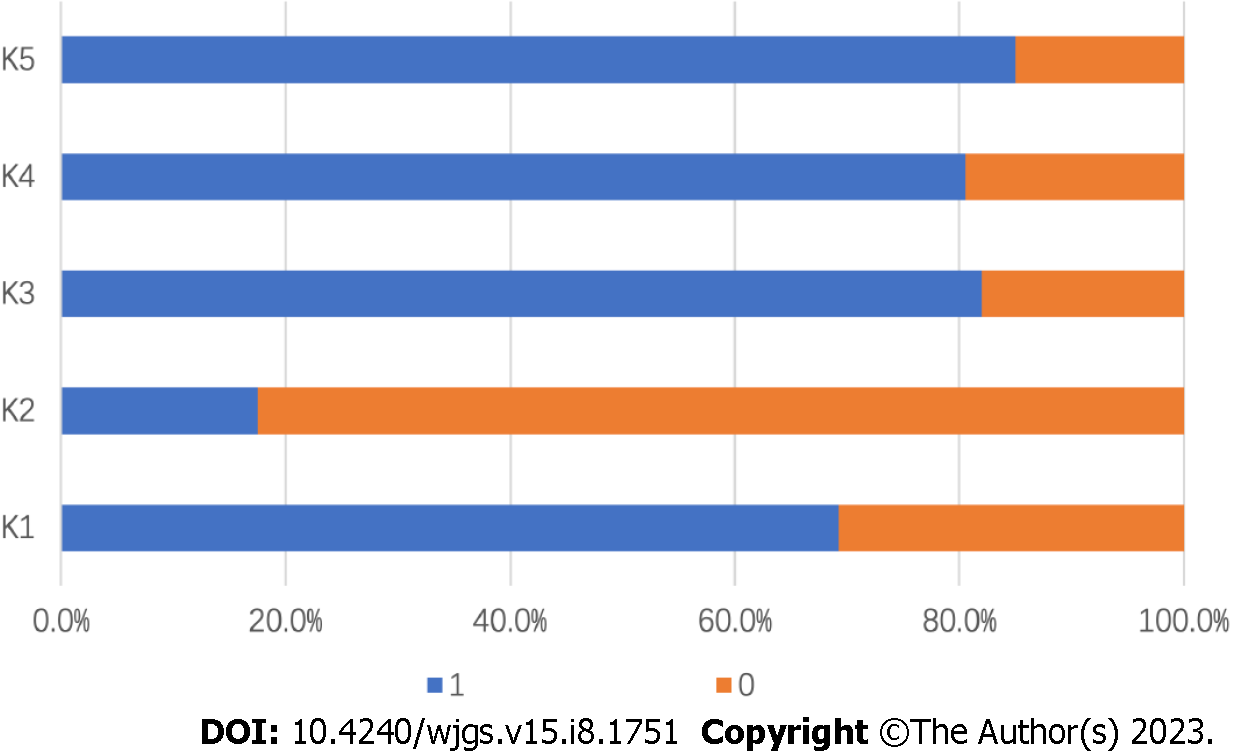

The KAP scores were 3.34 ± 1.42 (66.8%), 23.76 ± 2.81 (79.2%), and 5.75 ± 2.35 (52.3%), respectively (Table 1). Knowledge scores were significantly higher for participants from urban areas, with higher education levels, with professional or technical occupations, with higher family incomes, with a longer time since the last ESD, and without smoking or alcohol use history (all P < 0.05). The participants with a longer time since the last ESD and without alcohol drinking had significantly more positive attitudes regarding monitoring gastric cancer after ESD (both P < 0.01). Compared to their counterparts, patients with medical insurance, with a longer time since their last ESD, and who did not smoke or drink alcohol were more likely to practice well in monitoring cancer recurrence after ESD (all P < 0.05). The distribution of knowledge scores showed that over 80.0% of patients were aware that follow-up, reexamination, and cessation of smoking and drinking alcohol following ESD are necessary, while less than 20.0% knew that gastric cancer will relapse after ESD (Figure 1). In the attitude assessment, 66.3% of participants believed that reexamination after ESD is not necessary, and none wanted to undergo regular follow-ups after ESD (Table 2). According to the practice assessment (Table 3), over 80.0% of patients followed a low-salt diet, stopped drinking alcohol, and took dietary supplements or Traditional Chinese Medicine after ESD. A surprising 96.5% of patients gained or lost more than 5 kg after ESD, with only 18.0% of them exercising regularly.

| Characteristic | Number of participants | Knowledge score | Attitude score | Practice score | |||

| mean ± SD | P | mean ± SD | P | mean ± SD | P | ||

| Total | 400 | 3.34 ± 1.42 | 23.76 ± 2.81 | 5.75 ± 2.35 | |||

| Sex | 0.266 | 0.517 | 0.537 | ||||

| Male | 192 | 3.26 ± 1.46 | 23.86 ± 3.04 | 5.83 ± 2.46 | |||

| Female | 208 | 3.42 ± 1.38 | 23.68 ± 2.58 | 5.68 ± 2.25 | |||

| Age in yr | 0.063 | 0.930 | 0.689 | ||||

| ≤ 40 | 35 | 3.57 ± 1.12 | 23.83 ± 2.47 | 5.31 ± 1.94 | |||

| 41-50 | 56 | 3.57 ± 1.28 | 23.88 ± 2.34 | 5.73 ± 2.39 | |||

| 51-60 | 117 | 3.49 ± 1.36 | 23.62 ± 2.72 | 5.75 ± 2.45 | |||

| > 60 | 192 | 3.15 ± 1.52 | 23.81 ± 3.05 | 5.84 ± 2.35 | |||

| Residency | 0.001 | 0.425 | 0.510 | ||||

| Rural areas | 333 | 3.25 ± 1.46 | 23.71 ± 2.88 | 5.72 ± 2.34 | |||

| Urban areas | 67 | 3.79 ± 1.10 | 24.01 ± 2.40 | 5.93 ± 2.40 | |||

| Education | 0.001 | 0.418 | 0.737 | ||||

| Junior middle school or lower | 297 | 3.20 ± 1.48 | 23.66 ± 2.90 | 5.72 ± 2.33 | |||

| Senior middle school/technical secondary school | 55 | 3.71 ± 1.13 | 24.04 ± 2.50 | 5.69 ± 2.27 | |||

| Junior college/college or higher | 48 | 3.81 ± 1.10 | 24.13 ± 2.59 | 6.00 ± 2.59 | |||

| Occupation | 0.000 | 0.512 | 0.407 | ||||

| General staff or relevant personnel | 77 | 3.70 ± 1.15 | 23.95 ± 2.45 | 5.92 ± 2.45 | |||

| Professional and technical staff | 10 | 4.50 ± 0.53 | 24.60 ± 2.95 | 6.80 ± 2.97 | |||

| Others | 313 | 3.22 ± 1.47 | 23.69 ± 2.89 | 5.68 ± 2.30 | |||

| Medical insurance | 0.125 | 0.128 | 0.013 | ||||

| Yes | 384 | 3.32 ± 1.43 | 23.72 ± 2.69 | 5.69 ± 2.35 | |||

| No | 16 | 3.88 ± 1.03 | 24.81 ± 5.01 | 7.19 ± 2.07 | |||

| Family income in Yuan | 0.002 | 0.116 | 0.977 | ||||

| < 2000 | 51 | 2.92 ± 1.59 | 23.12 ± 2.30 | 5.69 ± 2.08 | |||

| 2000-5000 | 247 | 3.29 ± 1.47 | 23.89 ± 2.91 | 5.77 ± 2.37 | |||

| > 5000 | 102 | 3.69 ± 1.09 | 23.79 ± 2.79 | 5.75 ± 2.45 | |||

| The time since last ESD in mo | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | ||||

| ≤ 12 | 193 | 3.10 ± 1.41 | 23.17 ± 2.86 | 4.92 ± 1.92 | |||

| 13-24 | 121 | 3.40 ± 1.44 | 24.24 ± 2.72 | 6.13 ± 2.53 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 86 | 3.80 ± 1.28 | 24.44 ± 2.56 | 7.09 ± 2.24 | |||

| Family history | 0.215 | 0.479 | 0.639 | ||||

| Yes | 19 | 3.74 ± 1.05 | 24.21 ± 2.72 | 6.00 ± 1.97 | |||

| No | 381 | 3.32 ± 1.43 | 23.74 ± 2.82 | 5.74 ± 2.37 | |||

| Infection with Helicobacter pylori in the past or present | 0.984 | 0.295 | 0.886 | ||||

| Yes | 59 | 3.34 ± 1.17 | 24.12 ± 2.34 | 5.71 ± 2.11 | |||

| No/unclear | 341 | 3.34 ± 1.46 | 23.70 ± 2.89 | 5.76 ± 2.39 | |||

| Smoking history | 0.000 | 0.181 | 0.053 | ||||

| Yes | 53 | 2.53 ± 1.67 | 23.28 ± 2.57 | 5.17 ± 2.35 | |||

| No | 347 | 3.47 ± 1.34 | 23.84 ± 2.84 | 5.84 ± 2.34 | |||

| Drinking alcohol | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 2.57 ± 1.53 | 22.71 ± 3.04 | 4.71 ± 2.16 | |||

| No | 330 | 3.51 ± 1.34 | 23.99 ± 2.71 | 5.97 ± 2.33 | |||

| Pathological confirmation of early tumors after ESD | 0.033 | 0.611 | 0.031 | ||||

| Yes | 357 | 3.39 ± 1.40 | 23.79 ± 2.82 | 5.84 ± 2.33 | |||

| No/not detected | 43 | 2.91 ± 1.49 | 23.56 ± 2.80 | 5.02 ± 2.41 | |||

| Questions | Strongly agree | Agree | Fair | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

| 1. I am afraid of gastric cancer | 0 | 0 | 28 (7.0) | 219 (54.8) | 153 (38.3) |

| 2. I am satisfied with the endoscopic submucosal dissection | 0 | 0 | 27 (6.8) | 213 (53.3) | 160 (40.0) |

| 3. Despite receiving endoscopic submucosal dissection, I am still terrified of gastric cancer | 0 | 0 | 27 (6.8) | 220 (55.0) | 153 (38.3) |

| 4. I am terrified of gastric cancer recurrence | 0 | 0 | 27 (6.8) | 217 (54.3) | 156 (39.0) |

| 5. I do not believe reexamination is necessary after endoscopic submucosal dissection | 19 (4.8) | 265 (66.3) | 69 (17.3) | 47 (11.8) | 0 |

| 6. I am willing to undergo regular reexaminations and follow-ups according to the doctor’s advice | 0 | 0 | 98 (24.5) | 185 (46.3) | 117 (29.3) |

| Questions | No | Yes |

| 1. Do you have regular follow-up appointments in the Gastroenterology Outpatient Department after surgery? | 161 (40.3) | 239 (59.8) |

| 2. Do you follow a low-salt diet after surgery? | 66 (16.5) | 334 (83.5) |

| 3. Did you stop drinking alcohol after surgery? | 63 (15.8) | 337 (84.3) |

| 4. Did you have Helicobacter pylori reexamination after surgery, such as a C-urea breath test? | 309 (77.3) | 91 (22.8) |

| 5. Do you undergo regular gastroscopy reexaminations after surgery (3 mo, 6 mo, 9 mo, and 12 mo after surgery, then one gastroscopy every year afterward)? | 234 (58.5) | 166 (41.5) |

| 6. Do you undergo yearly reexaminations by abdominal and chest CT scans after surgery? | 286 (71.5) | 114 (28.5) |

| 7. Do you undergo yearly reexaminations of blood tumor biomarkers after surgery? | 275 (68.8) | 125 (31.3) |

| 8. Do you regularly exercise after surgery? | 328 (82.0) | 72 (18.0) |

| 9. Did you have significant body weight changes after surgery (more than 5 kilograms increased or decreased)? | 14 (3.5) | 386 (96.5) |

| 10. Has your sleep status improved since the surgery? | 296 (74.0) | 104 (26.0) |

| 11. Do you use dietary supplements or Traditional Chinese Medicine after surgery? | 67 (16.8) | 333 (83.3) |

Table 4 shows significant positive correlations between knowledge-attitude, knowledge-practice, and attitude-practice, with correlation coefficients of 0.405, 0.511, and 0.458, respectively (all P < 0.0001). The multivariate analysis further revealed that knowledge scores [odds ratio (OR) = 1.916; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.424-2.578; P < 0.001], attitude scores (OR = 1.253; 95%CI: 1.124-1.396; P < 0.001), and the duration since the last ESD of 13-24 mo (vs ≤ 12 mo since the last ESD; OR = 3.296; 95%CI: 1.761-6.172; P < 0.001) and ≥ 25 mo (vs ≤ 12 mo since the last ESD; OR = 5.768; 95%CI: 2.963-11.226; P < 0.001) were independent predictors of proactive practice (Table 5).

| Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | |

| Knowledge | 1.000 | - | - |

| Attitude | 0.405 (P < 0.001) | 1.000 | - |

| Practice | 0.511 (P < 0.001) | 0.458 (P < 0.001) | 1 |

| Factors | Univariate logistic regression | Multivariate logistic regression | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Knowledge score | 2.528 (1.893-3.375) | < 0.001 | 1.916 (1.424-2.578) | < 0.001 |

| Attitude score | 1.395 (1.260-1.545) | < 0.001 | 1.253 (1.124-1.396) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| M | Reference | - | ||

| F | 0.943 (0.606-1.466) | 0.794 | ||

| Age in yr | ||||

| ≤ 40 | Reference | - | ||

| 41-50 | 2.289 (0.807-6.495) | 0.119 | ||

| 51-60 | 1.820 (0.691-4.793) | 0.226 | ||

| > 60 | 1.795 (0.705-4.752) | 0.220 | ||

| Registered residence | ||||

| Rural area | Reference | - | ||

| Urban area | 1.085 (0.605-1.946) | 0.784 | ||

| Educational level | ||||

| Junior middle school or lower | Reference | - | ||

| Senior middle school/technical secondary school | 0.840 (0.428-1.645) | 0.611 | ||

| Junior college/college or higher | 1.233 (0.636-2.390) | 0.535 | ||

| Occupation | ||||

| General staff or relevant personnel | Reference | - | ||

| Professional and technical staff | 1.472 (0.380-5.701) | 0.576 | ||

| Others | 0.758 (0.440-1.308) | 0.320 | ||

| Medical insurance | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | ||

| No | 1.659 (0.588-4.680) | 0.339 | ||

| Family income in Yuan | ||||

| < 2000 | Reference | - | ||

| 2000-5000 | 1.066 (0.535-2.125) | 0.856 | ||

| > 5000 | 1.161 (0.542-2.490) | 0.701 | ||

| The time since last ESD in mo | ||||

| ≤ 12 | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| 13-24 | 3.788 (2.130-6.736) | < 0.001 | 3.296(1.761-6.172) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 25 | 7.743 (4.220-14.208) | < 0.001 | 5.768(2.963-11.226) | < 0.001 |

| Family history | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | ||

| No | 1.370 (0.365-2.952) | 0.945 | ||

| Infection with Helicobacter pylori in the past or present | ||||

| Yes | 0.652 (0.331-1.282) | 0.215 | ||

| No/unclear | Reference | - | ||

| Smoking history | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | ||

| No | 1.952 (0.918-4.148) | 0.082 | ||

| Alcohol drinking | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| No | 2.534 (1.246-5.154) | 0.010 | 1.160 (0.500-2.691) | 0.729 |

| Pathological confirmation of early tumors after ESD | ||||

| Yes | Reference | - | ||

| No/not detected | 0.493 (0.212-1.144) | 0.099 | ||

This is the first study to examine KAP regarding monitoring of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD. In terms of monitoring gastric cancer recurrences after ESD, participants’ average KAP scores indicated inadequate knowledge, good attitude, and poor practice. Significant and positive correlations were found between knowledge and attitude, knowledge and practice, and attitude and practice. Sufficient knowledge, a positive attitude, and at least 12 mo since the last ESD were independent predictors for correct practice. The lack of knowledge and insufficient practice in monitoring cancer recurrence may explain 89.2% (43/400) of pathologically confirmed early tumors after ESD.

In our study, KAP scores were significantly higher among patients with a longer time since ESD, indicating that these patients have more time to gain knowledge and improve their attitude and practice related to monitoring cancer recurrences. Cancer survivors with higher education and higher income were more likely to have the screening for second cancer or cancer recurrence[13]. In our study, in addition to the duration since the last ESD, residency, education, occupation, family income, and history of smoking or alcohol use were significantly associated with knowledge about monitoring cancer recurrences. Over 80% of the participants agreed that reexamination, follow-up, and quitting smoking and alcohol drinking are necessary after ESD. Surprisingly, less than 20% of participants correctly answered the question regarding the possibility of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD. Insufficient knowledge about cancer relapse may delay early detection of cancer recurrence, even if awareness may induce psychological stress that contributes to cancer incidence and progression[17]. Therefore, increasing awareness of cancer recurrence among EGC survivors is vital.

For patients with EGC after curative ESD, annual or biannual surveillance esophagogastroduodenoscopy and abdominal computed tomography are recommended for at least 5 years[18]. In spite of the fact that the majority of the participants were within 2 years of their last ESD, only 28.5% had yearly reexaminations by abdominal and chest computed tomography scans. It was interesting to note that over 80% of patients were aware of follow-up, reexamination, and cessation of smoking and drinking alcohol following an ESD. This paradox indicates that monitoring EGC recurrences after ESD requires putting knowledge into practice.

Despite the overall unsatisfactory practice score, we noticed some highlights. After ESD, 83.5% of the participants followed a low-salt diet, and 84.3% of the participants quit smoking and drinking alcohol. These actions may reduce the risk of recurrence of gastric cancer since high salt intake, heavy smoking, and combined smoking and alcohol exposure are associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer[19,20].

We noticed that higher knowledge and attitude scores were generally accompanied by increased practice scores. Pearson correlation analysis showed that knowledge-attitude, knowledge-practice, and attitude-practice were positively correlated, consistent with similar studies[21,22]. Moreover, multivariate linear regression analysis revealed that knowledge, attitude, and duration since the last ESD were independent predictors of practice. Therefore, providing patients with more time and improving their knowledge is a potentially effective way to promote practice in monitoring gastric cancer recurrence after ESD.

The discrepancy between a positive attitude, inadequate knowledge, and poor practice can be attributed to several factors. First, there may be a lack of awareness and education about the specific details and importance of post-ESD care. While participants may have positive attitudes based on a general understanding that monitoring is necessary, they lack in-depth knowledge about the specific actions required for effective monitoring and preventing cancer recurrence. Second, misconceptions or misunderstandings about post-ESD care may contribute to the disparity. Participants may hold positive attitudes but have incorrect beliefs or assumptions about the necessity of certain practices or the risks involved. Third, limited access to educational materials, healthcare professionals, and facilities providing post-ESD care, especially among participants from rural areas or lower socioeconomic backgrounds, can contribute to inadequate knowledge and poor practice. Furthermore, ineffective communication and a lack of clear instructions from healthcare providers can hinder the translation of positive attitudes into practical actions. Addressing these factors requires comprehensive efforts to facilitate the translation of positive attitudes into informed knowledge and effective practices.

The KAP concerning the monitoring of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD holds significant clinical implications. Primarily, it identifies patient understanding, attitudes, and behavioral gaps that can be addressed to enhance patient outcomes and decrease recurrence rates. Furthermore, understanding the KAP of patients allows for a more personalized approach to patient education and intervention strategies, helping to bridge the gap between positive attitudes and effective practices, especially in areas like follow-up schedules and lifestyle adjustments. Lastly, studying KAP has essential implications for resource allocation and healthcare policy, as it underlines areas of need such as patient education, access to healthcare services, and efficient communication between healthcare providers and patients.

In this study, data were collected by self-reporting, which might be less reliable than medical records and laboratory measurements due to self-reporting bias. In addition, as this study was conducted in Zhejiang, China, the results do not reflect the KAP of monitoring cancer recurrence globally. To better understand the KAP of monitoring gastric cancer recurrence around the world, more studies in more areas with larger sample sizes are needed.

In this study, the KAP of monitoring gastric cancer recurrences after ESD was assessed for the first time in EGC survivors following ESD. Participants showed a positive attitude toward monitoring gastric cancer recurrence after ESD, but more efforts are needed to improve their knowledge and practice.

Gastric cancer is a prevalent and deadly form of cancer worldwide, particularly in China, where it ranks as the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Early gastric cancer (EGC) refers to tumors located in the mucosa or submucosa of the stomach, and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is the recommended treatment. However, non-curative resection can occur, leading to an increased risk of local recurrence. Therefore, monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer after ESD is crucial for early detection and improved survival.

Although monitoring gastric cancer recurrence is important, little is known about the knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of EGC survivors regarding this issue. Understanding the KAP of patients can help healthcare practitioners develop strategies to improve monitoring practices and promote early detection of recurrence.

To assess the KAP of EGC survivors after ESD regarding monitoring the recurrence of gastric cancer. Specifically, the study aimed to evaluate KAP related to gastric cancer recurrence, reexamination, and follow-up. Additionally, the study aimed to identify sociodemographic factors associated with monitoring practices.

This cross-sectional study was conducted at a hospital in Zhejiang, China and involved 400 EGC survivors who underwent ESD. Participants completed a self-designed questionnaire consisting of 40 questions divided into four categories: Personal information and KAP. The questionnaire scores were calculated and analyzed using statistical methods, including t-tests, χ2 tests, and logistic regression analysis.

The study found that participants had moderate levels of knowledge, positive attitudes, and moderate levels of practice regarding monitoring gastric cancer recurrence. Knowledge scores were higher among participants from urban areas, with higher education levels, professional occupations, higher family incomes, longer time since the last ESD, and without smoking or alcohol use history. Participants with a longer time since their last ESD and without alcohol consumption had more positive attitudes. Factors associated with good monitoring practices included having medical insurance, longer time since the last ESD, and not smoking or drinking alcohol.

The study highlights the need to improve the knowledge and monitoring practices of EGC survivors after ESD. Educational interventions and targeted strategies should focus on enhancing patient understanding of the importance of monitoring gastric cancer recurrence and promoting regular reexamination and follow-up. Improving knowledge and attitudes can positively influence monitoring practices and contribute to early detection of gastric cancer recurrence.

Future research should focus on developing effective educational programs and interventions to improve patient knowledge and awareness of gastric cancer recurrence after ESD.

| 1. | Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 3325] [Article Influence: 554.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 2. | Xia C, Dong X, Li H, Cao M, Sun D, He S, Yang F, Yan X, Zhang S, Li N, Chen W. Cancer statistics in China and United States, 2022: profiles, trends, and determinants. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:584-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1790] [Cited by in RCA: 2515] [Article Influence: 628.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Kim GH. Systematic Endoscopic Approach to Early Gastric Cancer in Clinical Practice. Gut Liver. 2021;15:811-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Qian M, Sheng Y, Wu M, Wang S, Zhang K. Comparison between Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection and Surgery in Patients with Early Gastric Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim TK, Kim GH, Park DY, Lee BE, Jeon TY, Kim DH, Jo HJ, Song GA. Risk factors for local recurrence in patients with positive lateral resection margins after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2891-2898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sekiguchi M, Suzuki H, Oda I, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Kushima R, Saito Y. Risk of recurrent gastric cancer after endoscopic resection with a positive lateral margin. Endoscopy. 2014;46:273-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abdelfatah MM, Barakat M, Ahmad D, Ibrahim M, Ahmed Y, Kurdi Y, Grimm IS, Othman MO. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery in early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;31:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Probst A, Schneider A, Schaller T, Anthuber M, Ebigbo A, Messmann H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: are expanded resection criteria safe for Western patients? Endoscopy. 2017;49:855-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Choi MK, Kim GH, Park DY, Song GA, Kim DU, Ryu DY, Lee BE, Cheong JH, Cho M. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a single-center experience. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4250-4258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park JS, Choe EA, Park S, Nam CM, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Lee S, Kim HS, Jung M, Chung HC, Rha SY. Detection of asymptomatic recurrence improves survival of gastric cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2021;10:3249-3260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fujiya K, Tokunaga M, Makuuchi R, Nishiwaki N, Omori H, Takagi W, Hirata F, Hikage M, Tanizawa Y, Bando E, Kawamura T, Terashima M. Early detection of nonperitoneal recurrence may contribute to survival benefit after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2017;20:141-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shin DW, Baik YJ, Kim YW, Oh JH, Chung KW, Kim SW, Lee WC, Yun YH, Cho J. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice on second primary cancer screening among cancer survivors: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:74-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang Y, Soon YY, Ngo LP, Dina Ee YH, Tai BC, Wong HC, Lee SC. A Cross-sectional Study of Knowledge, Attitude and Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening among Cancer Survivors. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019;20:1817-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee F, Suryohusodo AA. Knowledge, attitude, and practice assessment toward COVID-19 among communities in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:957630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Serdar CC, Cihan M, Yücel D, Serdar MA. Sample size, power and effect size revisited: simplified and practical approaches in pre-clinical, clinical and laboratory studies. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2021;31:010502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 785] [Article Influence: 157.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thirunavukkarasu A, Al-Hazmi AH, Dar UF, Alruwaili AM, Alsharari SD, Alazmi FA, Alruwaili SF, Alarjan AM. Knowledge, attitude and practice towards bio-medical waste management among healthcare workers: a northern Saudi study. PeerJ. 2022;10:e13773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oh HM, Son CG. The Risk of Psychological Stress on Cancer Recurrence: A Systematic Review. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Min BH, Kim ER, Kim KM, Park CK, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim JJ. Surveillance strategy based on the incidence and patterns of recurrence after curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2015;47:784-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wu X, Chen L, Cheng J, Qian J, Fang Z, Wu J. Effect of Dietary Salt Intake on Risk of Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Nutrients. 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sjödahl K, Lu Y, Nilsen TI, Ye W, Hveem K, Vatten L, Lagergren J. Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to risk of gastric cancer: a population-based, prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:128-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | ul Haq N, Hassali MA, Shafie AA, Saleem F, Farooqui M, Haseeb A, Aljadhey H. A cross-sectional assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice among Hepatitis-B patients in Quetta, Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hamza MS, Badary OA, Elmazar MM. Cross-Sectional Study on Awareness and Knowledge of COVID-19 Among Senior pharmacy Students. J Community Health. 2021;46:139-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Elshimi E, Egypt; Marano L, Italy; Mohamed SY, Egypt; Prabahar K, Saudi Arabia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zhang XD