Published online Mar 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i3.408

Peer-review started: November 25, 2022

First decision: January 23, 2023

Revised: January 27, 2023

Accepted: March 3, 2023

Article in press: March 3, 2023

Published online: March 27, 2023

Processing time: 121 Days and 22.1 Hours

Acute esophageal mucosal lesions (AEMLs) are an underrecognized and largely unexplored disease. Endoscopic findings are similar, and a higher percentage of AEML could be misdiagnosed as reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade D (RE-D). These diseases could have different pathologies and require different treatments.

To compare AEML and RE-D to confirm that the two diseases are different from each other and to clarify the clinical features of AEML.

We selected emergency endoscopic cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with circumferential esophageal mucosal injury and classified them into AEML and RE-D groups according to the mucosal injury’s shape on the oral side. We examined patient background, blood sampling data, comorbidities at onset, endoscopic characteristics, and outcomes in each group.

Among the emergency cases, the AEML and RE-D groups had 105 (3.1%) and 48 (1.4%) cases, respectively. Multiple variables exhibited significantly different results, indicating that these two diseases are distinct. The clinical features of AEML consisted of more comorbidities [risk ratio (RR): 3.10; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.68–5.71; P < 0.001] and less endoscopic hemostasis compared with RE-D (RR: 0.25; 95%CI: 0.10–0.63; P < 0.001). Mortality during hospitalization was higher in the AEML group (RR: 3.43; 95%CI: 0.82–14.40; P = 0.094), and stenosis developed only in the AEML group.

AEML and RE-D were clearly distinct diseases with different clinical features. AEML may be more common than assumed, and the potential for its presence should be taken into account in cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with comorbidities.

Core Tip: The pathogenesis of acute esophageal mucosal lesion (AEML) is uncertain and is frequently misdiagnosed as reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade D (RE-D). Therefore, we compared the clinical features of AEML and RE-D using a single-center retrospective study. These esophageal diseases were distinguished based on the oral shape of the esophageal mucosal injury. Our results suggest AEML cases may be more prevalent than previously thought, as twice as many AEML cases were observed than RE-D cases. We found clear differences between these diseases and recommend that AEML is considered in cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Citation: Ichita C, Sasaki A, Shimizu S. Clinical features of acute esophageal mucosal lesions and reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade D: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(3): 408-419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i3/408.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i3.408

Acute esophageal mucosal lesion (AEML) is proposed in Japan and other Asian countries as a disease concept that unites black and non-black esophagus[1]. The proportion of black esophagus is quite rare, accounting for 0.2% and 3% in upper and emergency endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, respectively[2,3]. A severe case of AEML is considered a black esophagus[4]. AEML is observed mainly in older males with severe comorbidities presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding[5-7]. Circulatory insufficiency and gastric acid reflux have been suggested as factors associated with AEML[6-8]. However, the actual pathogenesis of AEML remains uncertain, and the disease has many indistinct aspects, including its clinical characteristics.

The endoscopic features of AEML include circumferential diffuse mucosal injury of the lower esophagus and sharp changes at the squamocolumnar junction[5]. This finding is similar to reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade D (RE-D). Consequently, AEML is frequently misdiagnosed as RE-D. Although reports have compared AEML with reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade C (RE-C) and RE-D[1], no studies have compared AEML with RE-D.

Therefore, this study aimed to clarify that AEML and RE-D are different diseases and to investigate the clinical features of AEML by comparing them with those of RE-D, which is a relatively established disease concept. Furthermore, since only a few studies have investigated the necessity for endoscopic hemostasis and outcomes such as stenosis development and in-hospital mortality, we also examined subjects with these outcomes.

This was a single-center, retrospective study.

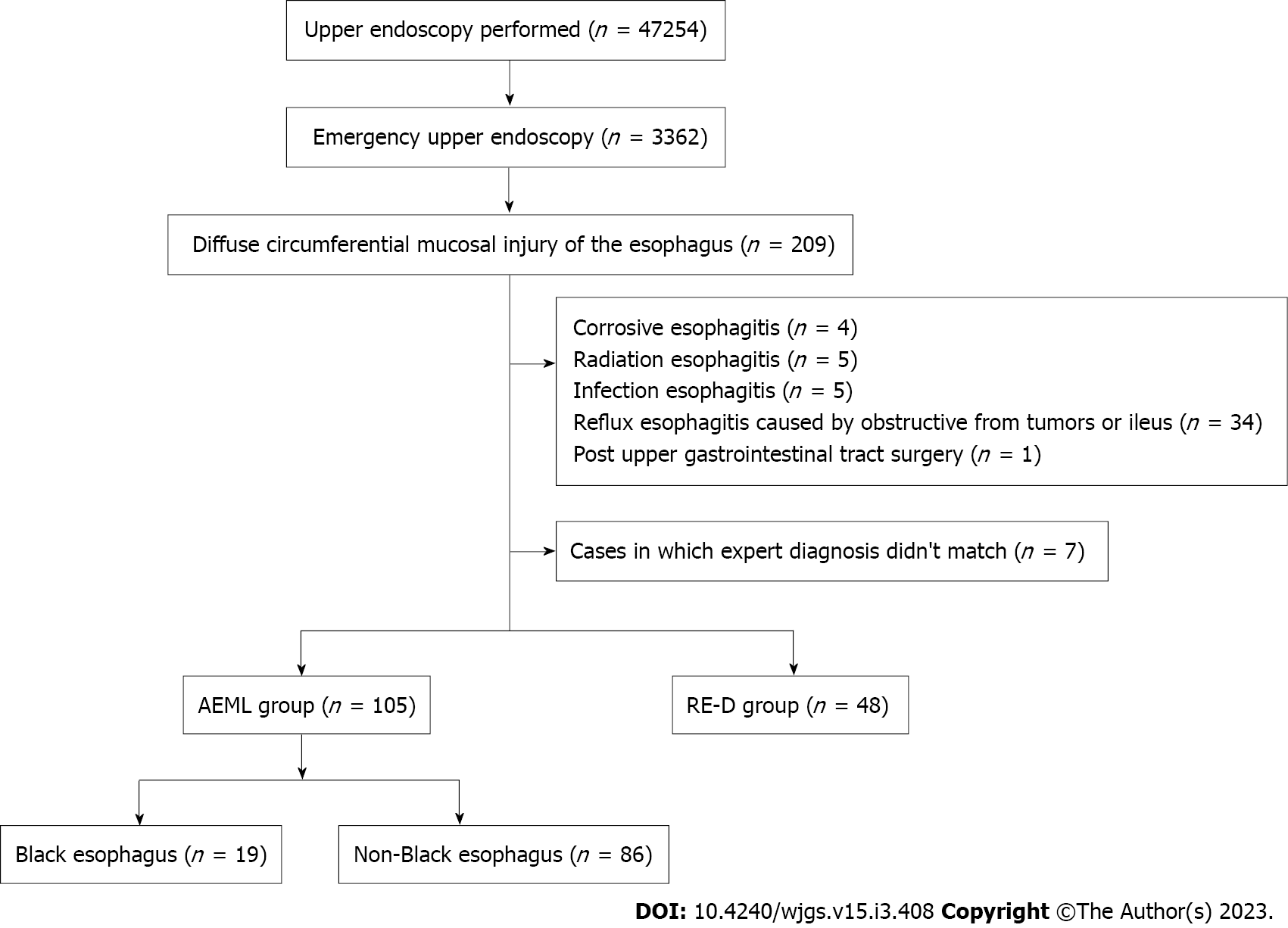

We assessed the medical records of all patients who underwent emergency upper endoscopy at Shonan Kamakura General Hospital in Kanagawa, Japan, between October 2016 and May 2022. Emergency upper endoscopy was defined as endoscopy performed within 24 h of the request. We included patients with diffuse circumferential mucosal injury of the esophagus and excluded patients with corrosive esophagitis, radiation esophagitis, infectious esophagitis, eosinophilic esophagitis, esophageal pemphigoid, and systemic sclerosis. We also excluded obstructive symptoms caused by tumors or ileus or post-upper gastrointestinal tract surgery.

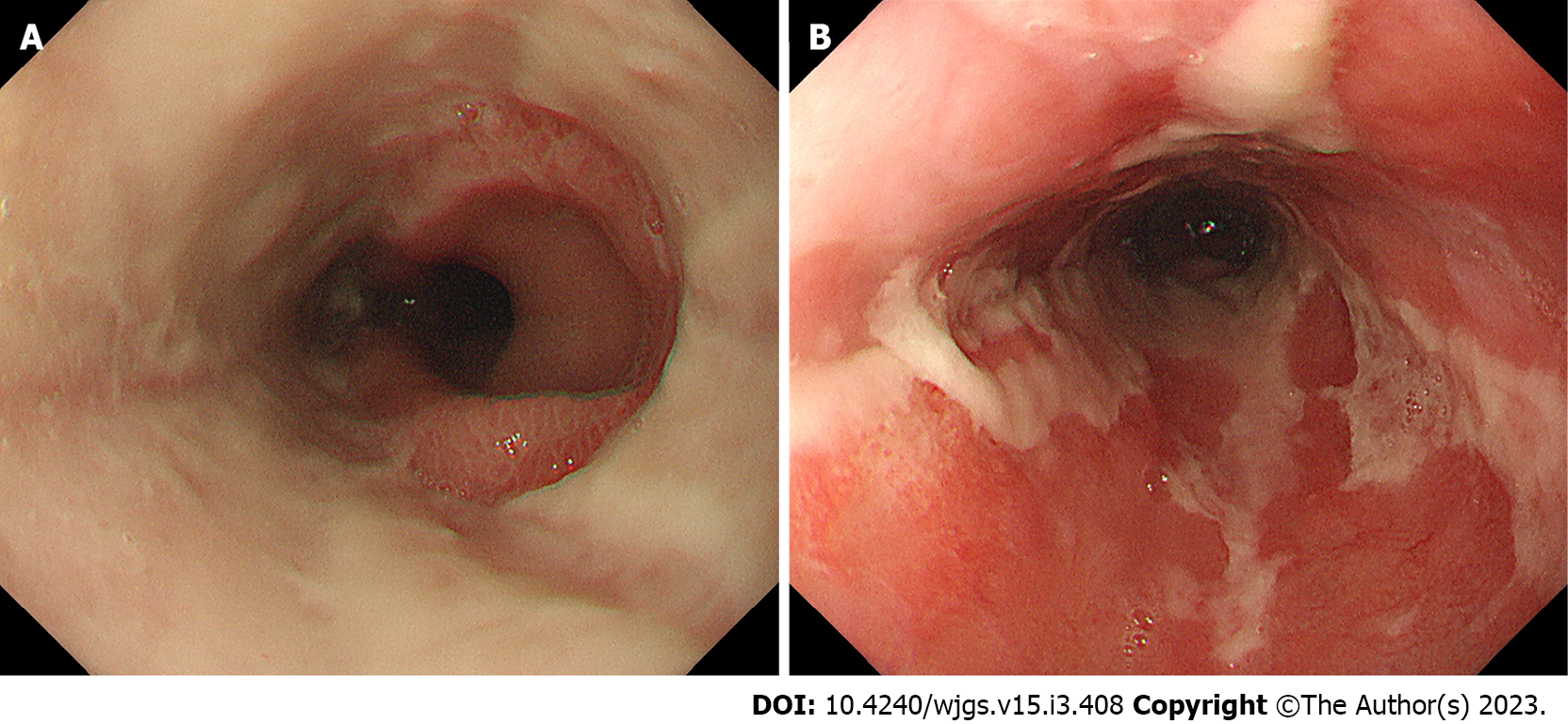

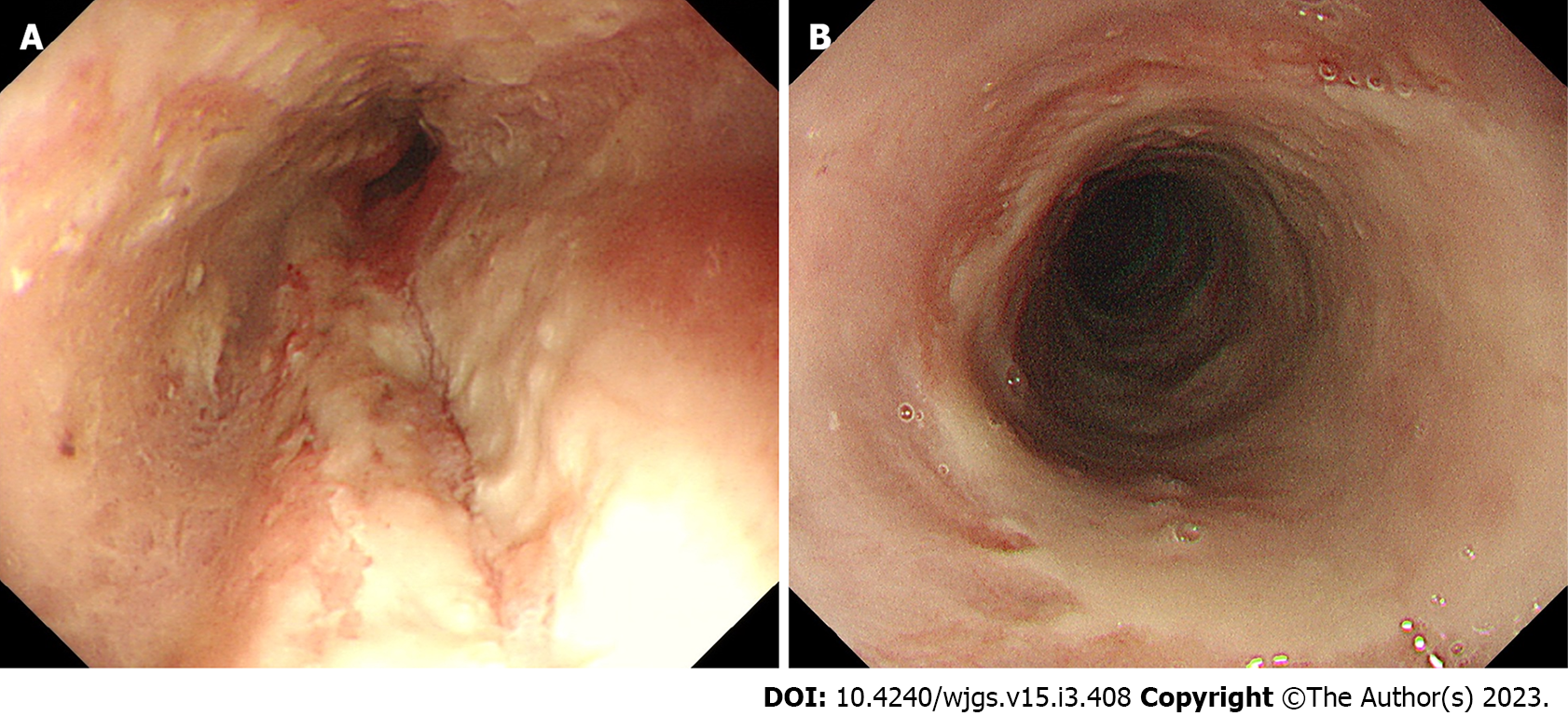

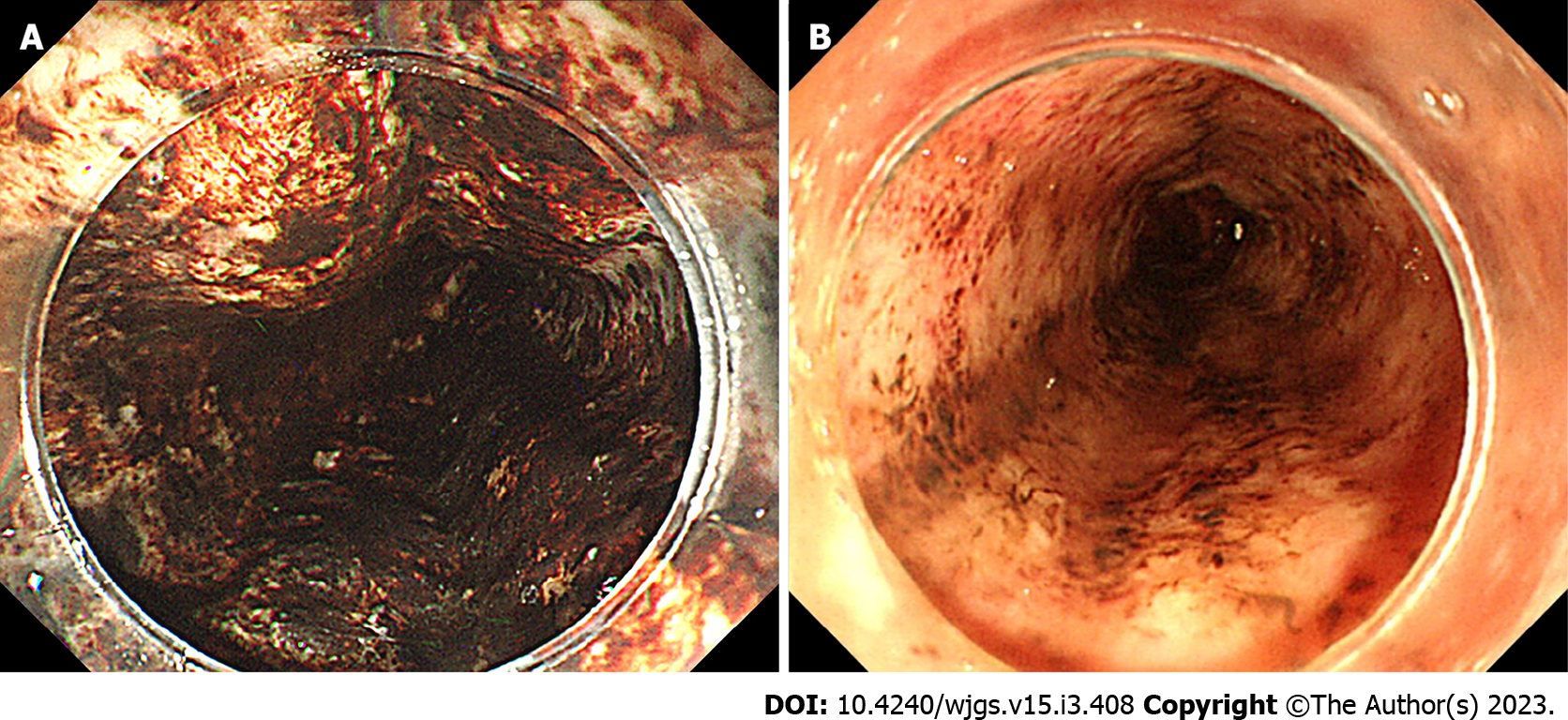

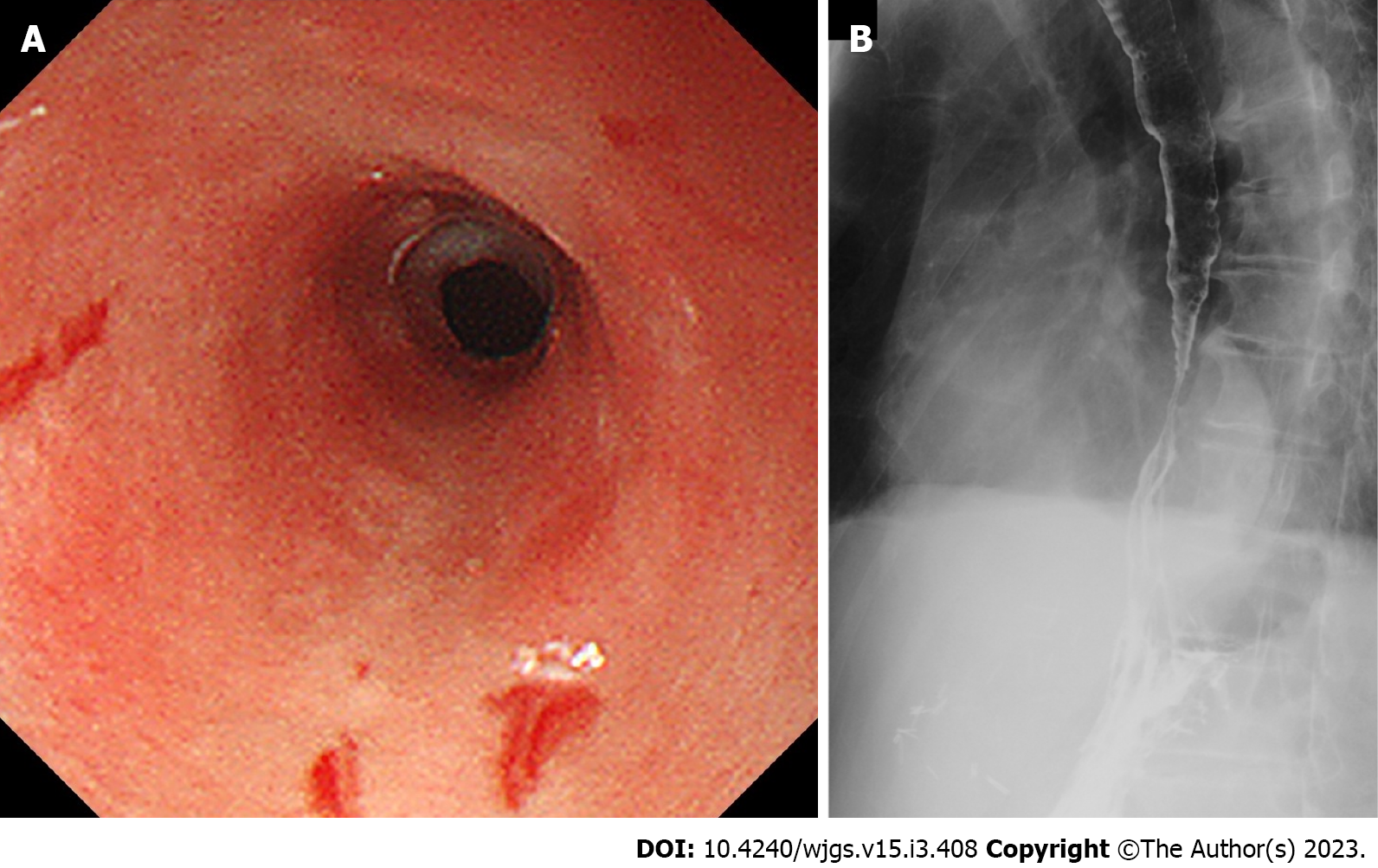

We categorized the patients into groups based on the esophageal mucosal injury’s shape on the oral side[1]. The RE-D group was defined as esophageal mucosal injuries that tapered off radially toward the oral side (Figure 1). In contrast, the AEML group was defined as esophageal mucosal injuries untapered radially toward the oral side and extended circumferentially (Figure 2). In the AEML group, black esophagus was defined as black esophageal mucosa appearing circumferentially (Figure 3A). We diagnosed black esophagus if a small amount of the black component was discovered (Figure 3B). However, the mucosa that did not meet this definition was considered non-black esophagus. These endoscopic findings were confirmed by two expert endoscopists (CI and AS), who were assigned to each group if their diagnoses were both consistent. Cases that did not match the two endoscopists’ diagnoses were excluded from this study. If multiple upper endoscopies were performed on the same patient, only the first episode of the most severe disease was used for analysis.

We did not set the case number in this study since the prevalence of AEML remains uncertain.

We compared the following factors between these two groups: Age, sex, chief complaint (hematemesis, black vomit, and black stool), presence of shock vitality, underlying conditions (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, liver cirrhosis, and previous malignancy), medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), antithrombotic drugs, steroids, antibiotics, and acid inhibitors, comorbidities at onset, blood sampling data (white blood cell, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin, blood glucose, and lactate), endoscopic findings (need for hemostasis, esophageal hiatal hernia, gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and atrophic gastritis), and other outcomes (presence of stenosis post-onset and mortality during hospitalization).

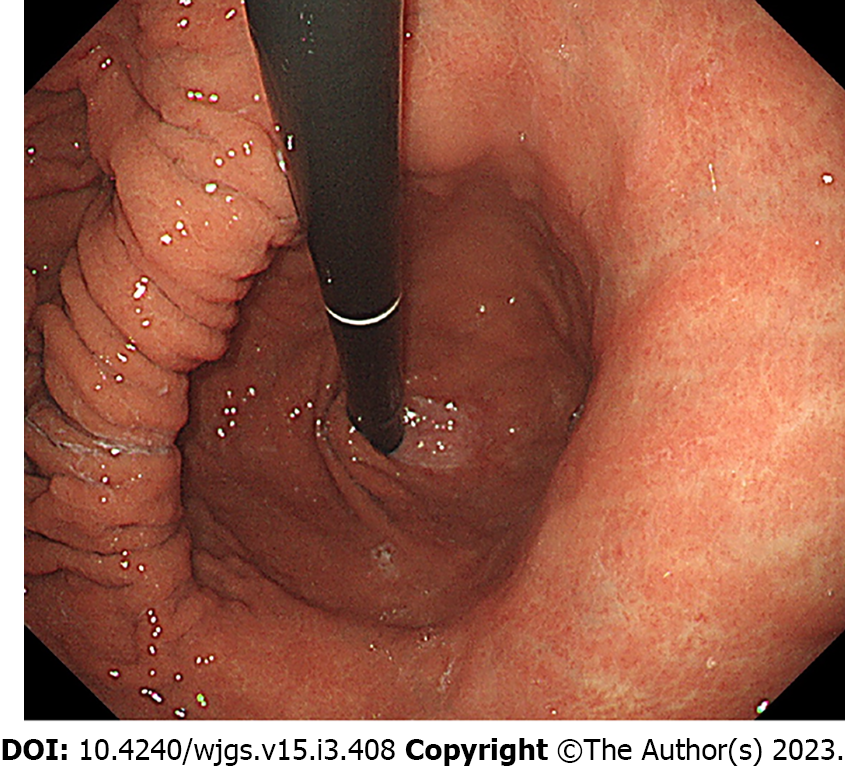

Shock vitality was defined as a shock index of > 1 at the time of presentation[9,10]. Blood sampling data were collected at the time of admission. Previous malignancy was defined as a previous diagnosis of malignant disease, regardless of the degree of progression, and those currently inactive. Acid inhibitors included proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), histamine H2-receptor antagonists, and potassium-competitive acid blockers. Comorbidities at onset indicated diseases that were simultaneously observed when the patient presented with an episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and treatment for malignancy was defined as a non-surgical treatment for malignancy, such as chemotherapy. Prerenal failure was defined as a creatinine level of > 1.5 mg/dL and fractional excretion of sodium of < 1% or urea nitrogen of < 35%[11]. Esophageal hiatal hernia was defined as an indirect finding of an esophageal hiatus widened by two or more scopes in the retroflex view (Figure 4)[12]. Atrophic gastritis, where a mucosal change was caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, was diagnosed by the vascular pattern associated with loss of gastric mucosal glands and loss of folds[13,14]. Patients with esophageal stenosis were considered to have stenosis when it was difficult to pass the upper endoscope (GIF-H260 or GIF-H290Z; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) within 6 mo.

Parametric and non-parametric continuous values were reported using mean ± standard deviation and median and interquartile ranges, respectively. Categorical variables are reported using numbers and percentages. Continuous and categorical values were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test and Fisher’s exact test, respectively. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Risk ratios (RRs), including 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and effect sizes (r) were calculated for binary and continuous outcomes, respectively[15]. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR version 1.55[16], which is a package for R statistical software (https://www.r-project.org/). Specifically, it is a modified version of the R commander designed to add statistical functions that are frequently used in biostatistics. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Sayuri Shimizu from the Department of Health Data Science, Yokohama City University.

Upper endoscopies were performed in 47254 cases, of which 3362 (7.1%) were emergency upper endoscopies. Of the emergency upper endoscopies, diffuse circumferential mucosal injury of the esophagus occurred in 209 cases (6.2%). Forty-nine cases were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. The expert endoscopists did not match the diagnosis in seven cases. The patients were classified into the AEML (n = 105) and RE-D (n = 48) groups. Among all upper endoscopic cases, AEML and RE-D accounted for 0.2% and 0.1%, respectively, whereas among all emergency upper endoscopic cases, AEML and RE-D accounted for 3.1% and 1.4%, respectively. In the AEML group, black and non-black esophagus accounted for 19 (18%) and 86 (82%) cases, respectively (Figure 5). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. AEML was more common in a younger age group (AEML group vs RE-D group; median 75.0 years vs 87.0 years; P < 0.001) and in male patients (58.1% vs 27.1%; RR: 2.15; 95%CI: 1.31–3.51; P < 0.001). Although no significant differences were observed regarding main complaints or the presence of shock vitality (27.6% vs 16.7%; RR: 1.66; 95%CI: 0.82–3.35; P = 0.16), patients with AEML were significantly more likely to have an underlying condition of diabetes mellitus (22.1% vs 8.3%; RR: 2.63; 95%CI: 0.96–7.18; P = 0.043) and previous malignancy (28.6% vs 10.4%; RR: 2.74; 95%CI: 1.13–6.63; P = 0.013). No significant difference was found in the type of medication administered. The blood sampling data showed significant differences in all collected items except for albumin levels (Table 2).

| Parameter | AEML (n = 105) | RE-D (n = 48) | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Black esophagus (n = 19) | Non-black esophagus (n = 86) | ||||

| Age in yr, median (IQR) | 75.0 (65.0–85.0) | 87.0 (78.0–91.3) | 0.34 | < 0.001 | |

| 83.0 (71.5–86.0) | 75.0 (65.0–84.0) | ||||

| Male | 61 (58.1) | 13 (27.1) | 2.15 (1.31–3.51) | < 0.001 | |

| 11 (57.9) | 50 (58.1) | ||||

| Chief complaint | 0.713 | ||||

| Hematemesis | 30 (28.3) | 16 (33.3) | |||

| 6 (31.6) | 24 (27.9) | ||||

| Black vomiting | 65 (61.0) | 26 (54.2) | |||

| 10 (52.6) | 54 (62.8) | ||||

| Black stools | 11 (10.5) | 6 (12.5) | |||

| 3 (15.8) | 8 (9.3) | ||||

| Presence of shock vitality | 29 (27.6) | 8 (16.7) | 1.66 (0.82–3.35) | 0.16 | |

| 6 (31.6) | 23 (26.7) | ||||

| Underlying conditions | |||||

| Hypertension | 49 (46.7) | 23 (47.9) | 0.97 (0.68–1.39) | 1 | |

| 13 (68.4) | 36 (41.9) | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 23 (22.1) | 4 (8.3) | 2.63 (0.96–7.18) | 0.043 | |

| 4 (21.1) | 19 (22.4) | ||||

| Chronic kidney disease | 19 (18.3) | 7 (14.6) | 1.24 (0.56–2.75) | 0.649 | |

| 5 (26.3) | 14 (16.5) | ||||

| Coronary artery disease | 13 (12.4) | 1 (2.1) | 5.94 (0.8–44.14) | 0.065 | |

| 3 (15.8) | 10 (11.6) | ||||

| Liver cirrhosis | 3 (2.9) | 2 (4.2) | 0.69 (0.12–3.97) | 0.649 | |

| 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.5) | ||||

| Previous malignancy | 30 (28.6) | 5 (10.4) | 2.74 (1.13–6.63) | 0.013 | |

| 7 (36.8) | 23 (26.7) | ||||

| Medications | |||||

| NSAIDs | 13 (12.4) | 2 (4.2) | 2.97 (0.70–12.66) | 0.148 | |

| 3 (15.8) | 10 (11.6) | ||||

| Antithrombotic | 28 (26.7) | 17 (35.4) | 0.75 (0.46–1.24) | 0.339 | |

| 3 (15.8) | 25 (29.1) | ||||

| Steroids | 4 (3.8) | 1 (2.1) | 1.83 (0.21–15.93) | 1 | |

| 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.7) | ||||

| Antibiotics | 8 (7.6) | 1 (2.1) | 3.66 (0.47–28.4) | 0.274 | |

| 2 (10.5) | 6 (7.0) | ||||

| Acid blockers | 42 (40.4) | 15 (31.2) | 1.28 (0.79–2.07) | 0.368 | |

| 10 (52.6) | 32 (37.6) | ||||

| Parameter | AEML (n = 105) | RE-D (n = 48) | Effect size, r | P value | |

| Black esophagus (n = 19) | Non-black esophagus (n = 86) | ||||

| White blood cell in μL, median (IQR) | 11650 (8300–14700) | 8700 (6750–10925) | 0.26 | < 0.001 | |

| 13100 (8750–16700) | 11200 (8225–14500) | ||||

| Hemoglobin in g/dL, (mean ± SD) | 10.70 (3.47) | 9.45 (2.81) | 0.2 | 0.026 | |

| 10.53 (3.58) | 10.78 (3.46) | ||||

| Albumin in g/dL, (mean ± SD) | 3.11 (0.97) | 3.00 (0.74) | 0.06 | 0.483 | |

| 2.91 (1.14) | 3.15 (0.93) | ||||

| BUN in mg/dL, median (IQR) | 36.60 (20.50–62.40) | 28.05 (16.90–37.92) | 0.21 | 0.009 | |

| 35.10 (18.95– 67.85) | 39.20 (20.65–61.90) | ||||

| Creatinine in mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.10 (0.87– 2.32) | 0.80 (0.63–0.94) | 0.37 | < 0.001 | |

| 1.34 (0.90–2.63) | 1.09 (0.84–2.10) | ||||

| Glucose in mg/dL, median (IQR) | 141 (110–196) | 124.00 (99.00–147.00) | 0.20 | 0.015 | |

| 137 (106–172) | 145 (111–203) | ||||

| CRP in mg/dL, median (IQR) | 1.59 (0.35–5.22) | 0.45 (0.23–1.93) | 0.24 | 0.003 | |

| 1.37 (0.31–4.68) | 1.64 (0.38–5.48) | ||||

| Lactate in mmol/L, median (IQR) | 3.18 (1.96–5.14) | 1.81 (1.38–2.38) | 0.40 | < 0.001 | |

| 3.45 (2.76–6.31) | 3.02 (1.94–4.75) | ||||

The AEML group had significantly more comorbidities at admission (57.5% vs 18.8%; RR: 3.10; 95%CI: 1.68–5.71; P < 0.001), with infection being the leading cause (21.7% vs 10.4%), followed by treatment for malignancy (8.5% vs 0%), prerenal failure (7.5% vs 2.1%), and after surgery (6.6% vs 2.1%) (Table 3).

| AEML (n = 105) | RE-D (n = 48) | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Black esophagus (n = 19) | Non-black esophagus (n = 86) | ||||

| Comorbidities | 61 (57.5) | 9 (18.8) | 3.10 (1.68–5.71) | < 0.001 | |

| Infection | 23 (21.7) | 5 (10.4) | |||

| 3 (15.8) | 20 (23.0) | ||||

| Treatment for malignancy | 9 (8.5) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 4 (21.1) | 5 (5.7) | ||||

| Prerenal failure | 8 (7.5) | 1 (2.1) | |||

| 1 (5.3) | 7 (8.0) | ||||

| After surgery | 7 (6.6) | 1 (2.1) | |||

| 1 (5.3) | 6 (6.9) | ||||

| Stroke | 4 (3.8) | 1 (2.1) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.6) | ||||

| Alcoholic ketoacidosis | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.6) | ||||

| Diabetic ketoacidosis/Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Pulmonary embolism | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Duodenal ulcer | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Liver disease | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

| Heart failure | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.1) | |||

| 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||||

The need for endoscopic hemostasis and endoscopic findings is shown in Table 4. RE-D showed more cases requiring endoscopic hemostasis (5.7% vs 22.9%; RR: 0.25; 95%CI: 0.10–0.63; P = 0.004). Esophageal hiatal hernias were significantly more frequent in the RE-D group (74.8% vs 97.9%; RR: 0.76; 95%CI: 0.68–0.86; P < 0.001). However, the percentage of atrophic gastritis was not significantly different (36.8% vs 31.2%; RR: 1.19; 95%CI: 0.73–1.94; P = 0.586), but gastric ulcers (29.2% vs 2.1%; RR: 14.17; 95%CI: 1.99–100.79; P < 0.001) and duodenal ulcers (19.8% vs 6.2%; RR: 3.20; 95%CI: 1.00–10.21; P = 0.033) were more significantly common in the AEML group.

| AEML (n = 105) | RE-D (n = 48) | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Black esophagus (n = 19) | Non-black esophagus (n = 86) | ||||

| Need of endoscopic hemostasis | 6 (5.7) | 11 (22.9) | 0.25 (0.10–0.63) | 0.004 | |

| 0 (0.0) | 6 (7.0) | ||||

| Hiatus hernia | 77/103 (74.8) | 46/47 (97.9) | 0.76 (0.68–0.86) | < 0.001 | |

| 14/18 (77.8) | 64/85 (74.4) | ||||

| Gastric atrophy | 39 (36.8) | 15 (31.2) | 1.19 (0.73–1.94) | 0.586 | |

| 5 (26.3) | 34 (39.1) | ||||

| Gastric ulcer | 31 (29.2) | 1 (2.1) | 14.17 (1.99–100.79) | < 0.001 | |

| 8 (42.1) | 23 (26.4) | ||||

| Duodenal ulcer | 21 (19.8) | 3 (6.2) | 3.20 (1.00–10.21) | 0.033 | |

| 5 (26.3) | 16 (18.4) | ||||

The outcomes for each group are shown in Table 5. Mortality during hospitalization tended to be higher in the AEML group (14.2% vs 4.2%; RR: 3.43; 95%CI: 0.82–14.40; P = 0.094), and esophageal stenosis was not significantly different (3.8% vs 0%; P = 0.309). However, esophageal stenosis occurred only in the AEML group, specifically in those with non-black esophagus (0% in black esophagus vs 4.7% in non-black esophagus). Esophageal stenosis developed at an average onset of 27 d. Furthermore, endoscopic dilatation was performed in two cases, while central venous nutrition was performed in two other cases (Figure 6).

| AEML (n = 106) | RE-D (n = 48) | Risk ratio (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Black esophagus (n = 19) | Non-black esophagus (n = 87) | ||||

| Mortality during hospitalization | 15 (14.2) | 2 (4.2) | 3.43 (0.82–14.40) | 0.094 | |

| 5 (26.3) | 10 (11.5) | ||||

| Esophageal stenosis | 4 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.309 | ||

| 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.6) | ||||

This study aimed to investigate whether AEML and RE-D are different diseases by distinguishing the two esophageal diseases according to the oral shape of the esophageal mucosal injury. Here, approximately twice as many AEML cases were observed than RE-D cases. Multiple variables in this study exhibited significantly different results, indicating that the two diseases may be attributed to different pathologies. The AEML group was significantly less likely to require endoscopic hemostasis. Although no significant differences were detected, mortality during hospitalization was higher in the AEML group than in the RE-D group. Stenosis was observed in three cases, only in the AEML group.

This study is similar to previous research that compared AEML with RE-C and D regarding patient background, endoscopic findings, and blood sampling data[1]; however, several differences were observed. The AEML group was younger, had more comorbidities at onset, more patients with diabetes mellitus or previous malignancy as an underlying condition, and less need for endoscopic hemostasis. Mortality during hospitalization was also at a high percentage, although not significantly different.

Diabetes mellitus and previous malignancy history were highly prevalent in the AEML group because they were associated with comorbidities, such as increased susceptibility to infection[17]. Comorbidities deteriorate the general condition, resulting in microcirculatory disturbances. Although gastric acid reflux and impaired peripheral circulation were considered possible etiologies of AEML[1,5-7], this study’s results, which included blood sampling data, strongly suggested an association with impaired peripheral circulation. The possible cause of the higher mortality observed in the AEML group may also be related to the high prevalence of comorbidities. Additionally, the RE-D group had more elderly patients because more older women with kyphosis tend to have reflux esophagitis[18-21]. Elderly age is reportedly to be a high-risk factor for bleeding with reflux esophagitis[22], which may be associated with the need for endoscopic hemostasis.

Notably, this is the largest study to investigate the characteristics of AEML. In contrast to previous research, our study included only emergency cases presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and used RE-D, which is an appropriate comparator for AEML. This study indicates that the incidence of AEML is higher than that of RE-D, suggesting that many AEML cases could be misdiagnosed as RE-D.

Although esophageal mucosal injury in AEML improves relatively quickly with the treatment of comorbidities, RE-D, which is caused by chronic gastric acid reflux, requires long-term acid-blocker therapy. Therefore, differentiating AEML from RE-D can prevent the unnecessary administration of acid blockers[1]. Although a stenosis risk of approximately 3.4% has been reported in reflux esophagitis cases[22], this study confirms that stenosis also develops in AEML cases. Several reports have shown that stenosis develops in black esophagus[23-25] and that black esophagus has a higher prevalence of stenosis than non-black esophagus[4]. However, this study indicated that stenosis could also develop in non-black esophagus. Stenosis was observed after approximately 1-mo; therefore, appropriate endoscopic follow-up is necessary even for non-black esophagus.

This study had some limitations. First, it was an observational study, and some of the possible information related to the outcomes, such as the duration of PPI administration and the history of treatment of varices with endoscopic variceal ligation, was not fully obtained. However, this is the largest study of AEML, adopting the more idealistic RE-D as a comparison. As a result, it may be possible to evaluate outcomes that could not be obtained in previous studies, such as the occurrence of stenosis. Second, the differences between AEML and RE-D in terms of endoscopic findings are not yet definitive. Although the present study was based on a previous report, further investigation is warranted.

In conclusion, AEML and RE-D were clearly distinct diseases with different clinical features. AEML develops about twice as frequently as RE-D and may be a more familiar disease. Therefore, the possibility of AEML should be considered in cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with comorbidities.

Recently, the concept of acute esophageal mucosal lesions (AEML), which encompasses both Black Esophagus and its milder variant, has been proposed, particularly in the Asian region.

The clinical manifestations of AEML remain inadequately understood and have been misdiagnosed as reflux esophagitis Los Angeles classification grade D (RE-D).

This study aimed to differentiate AEML from RE-D and to elucidate the clinical features of AEML.

We selected emergency endoscopic cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding characterized by circumferential esophageal mucosal injury and classified them into AEML and RE-D groups based on the shape of mucosal injury observed on the oral side. We subsequently examined patient demographics, blood sampling data, comorbidities at onset, endoscopic characteristics, and outcomes in each group.

Among the emergency cases, the incidence of AEML and RE-D were 3.1% and 1.4%, respectively. A comparison of multiple variables revealed significant differences, suggesting that these two conditions are distinct. The clinical features of AEML were characterized by a higher prevalence of comorbidities [risk ratio (RR): 3.10; P < 0.001] and a lower rate of endoscopic hemostasis compared with RE-D (RR: 0.25; P < 0.001). Additionally, in-hospital mortality was higher in the AEML group (RR: 3.43; P = 0.094), and stenosis was observed exclusively in the AEML group.

AEML and RE-D were clearly distinct diseases with different clinical features. AEML may be more prevalent than previously thought, and the potential for its presence should be taken into account in cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding accompanied by comorbidities.

In the future, we aim to conduct studies on a larger sample size across multiple institutions.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Gastroenterology Medicine Center, the Emergency Department, the General internal medicine department, and the Surgery Department of Shonan Kamakura General Hospital, who were involved in the patient care.

| 1. | Sakata Y, Tsuruoka N, Shimoda R, Yamamoto K, Akutagawa T, Sakata N, Iwakiri R, Fujimoto K. Comparison of Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Acute Esophageal Mucosal Lesion and those with Severe Reflux Esophagitis. Digestion. 2019;99:275-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:493-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Augusto F, Fernandes V, Cremers MI, Oliveira AP, Lobato C, Alves AL, Pinho C, de Freitas J. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy. 2004;36:411-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tatsumi R, Ohta T, Matsubara Y, Yoshizaki K, Sakamoto J, Sato R, Amizuka H, Kimura K, Furukawa S, Maemoto H, Orii F, Ashida T, Serikawa S. Examination of the severity of subtypes of acute esophageal mucosal lesion. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2014;56:3775-3785. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Tsumura T, Maruo T, Tsuji K, Osaki Y, Tomono N. Twelve cases of acute esophageal mucosal lesion. Dig Endosc. 2006;18:199-205. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ihara Y, Hizawa K, Fujita K, Matsuno Y, Sakuma T, Esaki M, Iida M. [Clinical features and pathophysiology of acute esophageal mucosal lesion]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2016;113:642-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kawauchi H, Ohta T, Matsubara Y, Yoshizaki K, Sakamoto J, Amitsuka H, Kimura K, Maemoto A, Orii F, Ashida T. [Clinicopathological study of acute esophageal mucosal lesion]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2013;110:1249-1257. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, Gualtieri N, Robilotti JG. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:29-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Allgöwer M, Burri C. ["Shock index"]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1967;92:1947-1950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koch E, Lovett S, Nghiem T, Riggs RA, Rech MA. Shock index in the emergency department: utility and limitations. Open Access Emerg Med. 2019;11:179-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pépin MN, Bouchard J, Legault L, Ethier J. Diagnostic performance of fractional excretion of urea and fractional excretion of sodium in the evaluations of patients with acute kidney injury with or without diuretic treatment. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:566-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ, Aye RW, Mercer CD, Low DE, Pope CE 2nd. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:541-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 2008;1:87-97. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 778] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 14. | Redéen S, Petersson F, Jönsson KA, Borch K. Relationship of gastroscopic features to histological findings in gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in a general population sample. Endoscopy. 2003;35:946-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Durlak JA. How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:917-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 821] [Cited by in RCA: 849] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software 'EZR' for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9275] [Cited by in RCA: 14471] [Article Influence: 1113.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, Shyr Y, Rubinstein SM, Rivera DR, Shete S, Hsu CY, Desai A, de Lima Lopes G Jr, Grivas P, Painter CA, Peters S, Thompson MA, Bakouny Z, Batist G, Bekaii-Saab T, Bilen MA, Bouganim N, Larroya MB, Castellano D, Del Prete SA, Doroshow DB, Egan PC, Elkrief A, Farmakiotis D, Flora D, Galsky MD, Glover MJ, Griffiths EA, Gulati AP, Gupta S, Hafez N, Halfdanarson TR, Hawley JE, Hsu E, Kasi A, Khaki AR, Lemmon CA, Lewis C, Logan B, Masters T, McKay RR, Mesa RA, Morgans AK, Mulcahy MF, Panagiotou OA, Peddi P, Pennell NA, Reynolds K, Rosen LR, Rosovsky R, Salazar M, Schmidt A, Shah SA, Shaya JA, Steinharter J, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Subbiah S, Vinh DC, Wehbe FH, Weissmann LB, Wu JT, Wulff-Burchfield E, Xie Z, Yeh A, Yu PP, Zhou AY, Zubiri L, Mishra S, Lyman GH, Rini BI, Warner JL; COVID-19 and Cancer Consortium. Clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1907-1918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1195] [Cited by in RCA: 1304] [Article Influence: 217.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hosogane N, Watanabe K, Yagi M, Kaneko S, Toyama Y, Matsumoto M. Scoliosis is a Risk Factor for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Adult Spinal Deformity. Clin Spine Surg. 2017;30:E480-E484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fujimoto K. Review article: prevalence and epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 8:5-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shimazu T, Matsui T, Furukawa K, Oshige K, Mitsuyasu T, Kiyomizu A, Ueki T, Yao T. A prospective study of the prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease and confounding factors. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:866-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Furukawa N, Iwakiri R, Koyama T, Okamoto K, Yoshida T, Kashiwagi Y, Ohyama T, Noda T, Sakata H, Fujimoto K. Proportion of reflux esophagitis in 6010 Japanese adults: prospective evaluation by endoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sakaguchi M, Manabe N, Ueki N, Miwa J, Inaba T, Yoshida N, Sakurai K, Nakagawa M, Yamada H, Saito M, Nakada K, Iwakiri K, Joh T, Haruma K. Factors associated with complicated erosive esophagitis: A Japanese multicenter, prospective, cross-sectional study. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:318-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 23. | Kosaka M, Kono Y, Nakagawa M. Gastrointestinal: Acute esophageal necrosis causing severe esophageal stenosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Barrientos Delgado A, Martínez Tirado MP, Martín-Lagos Maldonado A, Palacios Pérez Á, Casado Caballero FJ. [Extensive esophageal stenosis secondary to acute necrotizing esophagitis]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;38:327-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gómez ÁA, Guerrero D, Hani AC, Cañadas R. [Acute necrotizing esophagitis (black esophagus) with secondary severe stenosis]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2015;35:349-354. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Cicala M, Italy; Zhuang ZH, China S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Fan JR