Published online Oct 27, 2023. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v15.i10.2108

Peer-review started: June 8, 2023

First decision: July 7, 2023

Revised: July 17, 2023

Accepted: August 15, 2023

Article in press: August 15, 2023

Published online: October 27, 2023

Processing time: 140 Days and 20.2 Hours

The total mesorectal excision (TME) approach has been established as the gold standard for the surgical treatment of middle and lower rectal cancer. This approach is widely accepted to minimize the risk of local recurrence and increase the long-term survival rate of patients undergoing surgery. However, stan

Core Tip: Denonvilliers’ fascia, an influential separating and barrier structure surrounding the rectum, is of paramount significance to the quality of life and the protection of pelvic autonomic nerves following surgery for rectal cancer.

- Citation: Chen Z, Zhang XJ, Chang HD, Chen XQ, Liu SS, Wang W, Chen ZH, Ma YB, Wang L. From basic to clinical: Anatomy of Denonvilliers’ fascia and its application in laparoscopic radical resection of rectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023; 15(10): 2108-2114

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v15/i10/2108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v15.i10.2108

Rectal cancer, one of the most common cancers worldwide[1], is currently treated with a complete surgical approach. Heald et al[2,3] proposed that total mesorectal excision (TME) is the gold standard for the surgical treatment of middle and low rectal cancer and that the integrity of mesorectal specimens can be utilized as an essential criterion for evaluating surgical quality and has the function of predicting tumor recurrence.

As reported[2], the most frequent postoperative complications of rectal cancer are urination disorder and sexual dysfunction caused by intraoperative pelvic autonomic nerve (PAN) damage. These two complications have an incidence rate of 30%-60% and 50%-70%, respectively, and severely affect the postoperative quality of life of patients. The precise separation of planes in front of the rectum was not overemphasized in the early surgical description of Heald. Importantly, recent years have witnessed the constant development of TME technology for rectal cancer and the increasing requirements for PAN preservation, which enables the selection of scope of radical resection for rectal cancer and the better preservation of postoperative urinary, reproductive, and defecation functions of patients to become an important issue that must be solved urgently. It has been extensively demonstrated that the removal of Denonvilliers’ fascia (DVF) during TME is a primary contributor to postoperative urogenital dysfunction in patients with rectal cancer[4]. Nonetheless, there is currently a paucity of long-term follow-up results on DVF-preserving TME (iTME), and it is yet to be reported on the results of long-term research on whether DVF preservation affects the long-term survival rate and increased local recurrence rate of patients. At the moment, it is a consensus to free the posterior and lateral anatomical levels of the rectum during TME, that is, freeing along the fascia propria of the rectum. However, the freeing of the anterior rectal wall and DVF-related levels is still debatable[5]. Accordingly, this study explores the anatomy of DVF and its use in surgery in greater detail and analyzes the comprehension of DVF and its preservation or not, thus providing a further reference for the selection of surgical treatment modes for middle and low rectal cancer.

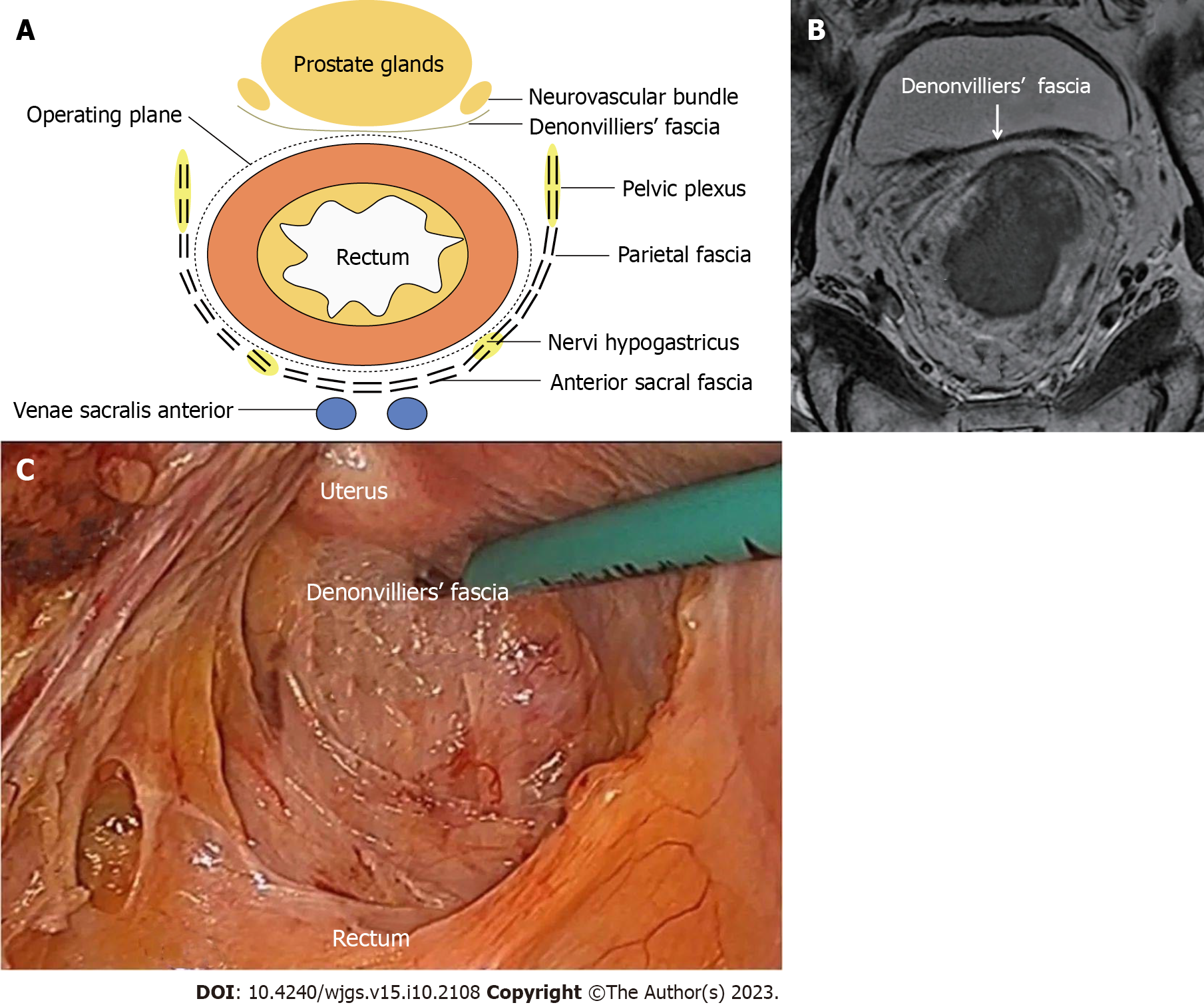

The anatomical position of DVF and its association with adjacent organs are responsible for its critical role in surgery for rectal cancer and influence the choice of surgical plane in front of the rectum during TME. This structure can be understood to some extent through anatomy and embryology (Figure 1A). At present, three basic hypotheses exist for the embryonic origin of DVF, including peritoneal fusion of embryo dead sac, condensation of embryo mesenchyme, and mechanical pressure. According to certain experts[5], DVF is formed through peritoneal fusion. Another opinion[4] holds that DVF formation is not derived from the occurrence of peritoneal fusion or pelvic dead sac of peritoneum. Moreover, DVF is a tension-induced structure, rather than a fascia fusion. DVF formation, whether caused by peritoneal fusion or tension, is the result of fusion or compression, which certainly results in its thickening structure. Under the light microscope, DVF is observed to have a single-layer, double-layer, multi-layer, or composite single-layer structure. Nevertheless, DVF has not been observed to be stratified to the naked eye in practically all individuals, and individual DVF is partially separated into two layers of vacuolated structures. Nonetheless, such individuals may also be particular. This structure has also been corroborated in the studies by Abdelrahman[6] and Wang et al[7].

The DVF structure was first discovered in male cadavers and then accepted by surgeons. However, the structure of DVF in females has not been thoroughly characterized, since physicians seldom find structures identical to DVF in males between the rectum and vagina after surgery. Hence, the presence of DVF in females has been controversial. However, mounting embryological, anatomical, and histological studies show the existence of DVF in females, including the structure of the rectovaginal septum. Despite no agreement on the embryonic origin of DVF, three theories including tension induction, mesenchyme, and peritoneal fusion all support the concept of DVF as a separate structure that neither belongs to the fascia propria of the rectum nor to the urogenital system[8-11]. Frizzell et al[12] observed that DVF fused with the anterior mesorectal fascia in imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging and therefore was difficultly differentiated and that the above two types of fascia exhibited a low-signal shadow of a single-layer linear structure after being reflected between the anterior rectal wall of the rectum and vagina, the seminal vesicle and the prostate, and peritoneum (Figure 1B). Another researcher discovered that intraoperative observations (endorectal ultrasound) were completely consistent with the anatomical course of DVF and that DVF divided the rectum and urogenital organs into posterior prostatic space and anterior rectal space, among which the latter existed objectively as the anatomical plane of separation plane during TME. A histological study[13] revealed that DVF was markedly stratified and varied among individuals, manifesting as a variety of distinct configurations. Retrospective studies of laparoscopic surgery videos[14,15] demonstrated the obvious stratification of DVF (Figure 1C). A prior study[11] unraveled that the original structure of DVF was easily disrupted by intraoperative exploration. In addition, the loose porous tissue between the seminal vesicle and the DVF has been questioned as an artificial structure formed by the drawing tension generated by the surgical procedure[16]. As a result, further multi-center fundamental and clinical studies are warranted to identify whether the anatomical structure of DVF is stratified. Although the embryonic origin of DVF remains undetermined, the differences in the anatomical structure of DVF between males and females are recognized by most experts.

The association of DVF with perirectal fascia and ligaments is barely reported in both domestic and foreign literature at present. Perirectal fascia and ligaments include the fascia propria of the rectum and the perirectal fat, nerves, and blood vessels, the presacral fascia and sacrococcygeal ligament behind the rectum, the DVF in front of the rectum, the rectal ligament on the side of the rectum, and some unclear fascia. Scholars at home and abroad have individually detailed the aforementioned structures in the past. Nevertheless, the relationship among these structures has been rarely described. This issue has been described by Zhang et al[17] in some detail: under peritoneal reflection, the anterior layer of DVF merges to both sides with the presacral fascia behind the rectum, forming the second cyclic structure of the rectum; the posterior layer of DVF directly merges with the rectum to generate the fascia propria of the rectum, constituting the first cyclic structure of the rectum; the pelvic parietal peritoneum and piriformis fascia form the third cyclic structure. The above discussion creatively provides a systematic overview of the overall association of perirectal mesentery. However, additional research on anatomy and histology is still currently necessary to further understand this topic.

DVF is a thin fascial layer that connects the rectum and its mesentery to the posterior wall of the seminal vesicle or prostate of males or the vagina of females, which originates upward from the peritoneal reflection to the prostate apex and the perineal central tendon, with some fibers forming the intramuscular fibers of the anal sphincter. DVF progressively thins to the sides and extends with the posterior pelvic fascia, separating the anterior rectal space into two independent fascia spaces: the anterior rectal space and the posterior prostatic space[18]. The incision is conducted along the Denonvilliers line (the inverted thickening line of the pelvic floor peritoneum, that is, the projection of DVF on the peritoneal surface) from the lowest point of the pelvic floor peritoneum directly into the large anterior rectal space behind DVF. The Denonvilliers line extends laterally as a yellow-white borderline between the mesorectum and the pelvic fascia, which is a crucial anatomical landmark during TME[19]. During the surgery, DVF is closely connected with the seminal vesicle or prostate in males or the posterior wall of vagina in females, with numerous blood vessels in the space, which is difficult to separate during the surgery, particularly for patients who had underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Posteriorly to the rectum, the superior hypogastric plexus and hypogastric nerve of the PAN branch course between the inside (also named the anterior fascia of the hypogastric nerve) and outside of the pelvic fascia. In most individuals, the fascia propria of the rectum exhibits a complete columnar surface contour on the lateral side, from which the smooth interface may be separated. Some nerves and blood vessels course to the fascia propria of the rectum only at the "lateral ligament" position. The neurovascular bundle (NVB) in males is located below the seminal vesicle in the front and travels through DVF tissues via the anterolateral side, whose branches are distributed in the prostate and seminal vesicle[18]. Liang et al[20] investigated the association between autonomic nerves and the prerenal fascia-presacral fascia in 7 cadaveric specimens and 52 patients with rectal cancer who underwent laparoscopic excision and observed that the abdominal aortic plexus, superior hypogastric plexus, hypogastric nerve, and inferior hypogastric were located in the posterolateral side of the presacral fascia-presacral fascia. Histological examination unveiled that nerve fibers were located behind fascia, with some thinner fibers in the fascia. Hence, when the tissues behind the descending mesocolon and mesorectum are separated during the surgery for rectal cancer, the basic skills to protect nerves are as follows: maintaining the integrity of the prerenal fascia-presacral fascia (Gerota fascia) and dissection in the fusion space between it and mesentery. Accordingly, the maintenance of the fascia integrity is the anatomical basis and fundamental strategy for protecting the autonomic nerve in surgery for rectal cancer surgery.

The anterior separation of DVF needs to be performed during the dissection of the anterior rectal space in laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer, which is in accordance with the surgical protocol for rectal cancer optimized by Heald et al[21] and fulfills the standards of TME. Moszkowicz et al[22] proposed that anus-preserving surgery for rectal cancer primarily aims to improve the quality of life of patients and diminish the risk of local tumor recurrence, with the second goal of minimizing nerve damage and preserving organ function. As a result, DVF should not be separated in patients with tumor infiltration in the mesentery if the bottom of the seminal vesicle is not completely exposed but should be separated in front of the DVF. For patients with serious tumor infiltration, a portion of the seminal vesicle (male) or posterior vaginal wall (female) should be excised. Overall, the scope of alternative resection should be selected based on the extent of infiltration and specific location for patients with tumor-infiltrating anterior mesorectum. The resection scope is 1 cm above the peritoneal reflection and down to 0.5 cm from the seminal vesicle (male) or 5 cm below the peritoneal reflection (female) to ensure the integrity of the anterior mesentery. After excision, the anterior lobe of the DVF is shaped in an inverted "U" from both sides to the inner side of the NVB. When invaded by a tumor, the fascia should be separated downward in front of it. If the condition is severe, a portion of the seminal vesicle (male) or the posterior vaginal wall (female) should be excised. After the separation of the anterior and posterior rectal spaces, the lateral rectal space should be separated from the anterosuperior side toward the posteroinferior side, and the sacred plane should be found to ensure complete mesorectum wrapping, which can prevent damage to the pelvic plexus or the NVB. Specifically, the membrane bridge is first incised in an arc 1 cm above the peritoneal reflection and directly to the anterior space of the DVF. A free space is observed in front of the thick anterior lobe of DVF under the magnifying effect of laparoscopy or robot, which is similar to the structure of "hairs of the angel". Then, it is facile to enter the anterior space of DVF through this space. Because of the dense anterior lobe of DVF, it is simple to maintain the integrity of the anterior lobe and mesentery of DVF. Furthermore, the 1 cm of peritoneum on the peritoneal reflection can be used for intraoperative retraction, which facilitates the exposure of the loose connective tissues in the anterior rectal space and the expansion of the surgical operation space and causes difficulty in fogging the laparoscopic mirror. In this way, it is extremely beneficial for pelvic floor operation in male patients with contracted pelvis. The hypogastric nerve, hypogastric nerve plexus, and subabdominal fascia are all covered by the first layer of fascia (DVF) and the anterior abdominal fascia. Importantly, the anterolateral side of this layer is the most key anatomical site. NVB can be found but is not always visible after the anterior lobe of DVF is transected. This phenomenon can be explained by the fact that NVB cannot be found when the incision line is located before the stratification of the anterior lobe of DVF, since NVB is covered by the middle layer of the anterior lobe of DVF after stratification; however, NVB is obviously exposed and has a sponge-like structure when the incision line is located after the stratification of the anterior lobe of DVF because its surface is not covered by membranous tissues. Accordingly, the NVB is not ensured to be undamaged if the surgical plane is selected between the first and second layers at the semi-prostate angle level. The third layer originates from the posterior bladder neck and then courses upward to attach to the second layer while crossing the upper surface of the bladder to form a common layer. This layer is separated by loose connective tissues from the lower bladder fascia and the upper peritoneum. Meanwhile, it receives some NVB branches from both sides, similar to the second layer. Some researchers consider that this layer is the third layer of DVF, not the bladder-related fascia, because it is completely isolated from the bladder that is covered by the adventitia. Additionally, this layer extends upward and connects to the second layer, which is considered one of the mentioned DVF complexes. Furthermore, at 2 and 10 o'clock directions, NVB specifies the location of the second and third layers with a highly complicated neural network, where there was no evident dissociative innervation, thus enabling us to believe that this layer is one of the multi-layer DVF complexes. According to Lu et al[23], the surgery should be performed with an approach above the peritoneal reflection. Next, separation should be conducted in close proximity to the DVF during the surgery. The DVF should be severed near the bottom of the seminal vesicle for male patients and 5 cm below the peritoneal reflection for female patients. The separation is subsequently continued by entering the space between the fascia propria of the rectum and the DVF. This surgery not only maintains the integrity of the local fascia propria of the rectum during excision, but also protects the autonomic nerve and prevents seminal vesicle damage. This surgery method should be widely used in clinical practice since it not only is beneficial for reducing mesangial injury but also elevates the complete rate of anterior mesangial resection. Meanwhile, it is useful for preventing or avoiding bleeding and peripheral nerve injury during pelvic free surgery to understand the interaction between DVF and surrounding tissues. Finding and dissecting DVF and elaborating on the surgical approach and technology for the anterior rectal space provide essential surgical experience in addressing this challenging and critical issue.

Dissection anterior to the DVF is not recommended when the tumor does not invade the fascia propria of the rectum or DVF[24], since the NVB coursing from the tail of the seminal vesicle to the bladder, seminal vesicle, prostate, and urethra in males is easily damaged during this surgery, therefore resulting in the occurrence of postoperative urogenital dysfunction. DVF should be removed when the tumor is located in the anterior wall of the rectum or invades the fascia propria or DVF, the local tumor is at the late stage, or edema and fibrosis changes occur in the focus due to preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy. A prior study[25] demonstrated that DVF was directly connected to the fascia propria anterior to the rectum, contributing to difficulty in its dissection. Hence, the anatomy should be conducted in front of the DVF during the surgery, and attention should be paid to NVB protection when it reaches the anterior side of the mesorectum. The author recommends that the region in front of the DVF and spaces of the seminal vesicle, the vas deferens, and the fascia propria of prostate should be dissected for males with tumors in the anterior rectal wall or a tumor at > T2 stage who receive preoperative neoadjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy. For female patients, the region in the front of the DVF and the space of the fascia of the posterior vaginal wall should be dissected. When it reaches the anterior side of the rectum, the DVF can be cut off and dissected along the fascia propria surface outside the mesentery of the anterior side of the rectum, preserving as much as possible the integrity and continuity of the anatomical plane and preventing fascia plane distortion due to insufficient or excessive traction tension.

Patients are pursuing radical surgery with increasing concern for postoperative prognosis and quality of life as their requirements for postoperative quality of life increase[26]. Previous research[27] revealed that after laparoscopic radical resection for rectal cancer, approximately 70% of patients might develop dysuria, approximately 45%-55% experienced erectile dysfunction, and 40% suffered from ejaculatory dysfunction and that the above adverse outcomes were related to the damage to the rectum, abdominal cavity, and pelvic cavity during the surgery. It has been reported that intraoperative fascia preservation could substantially improve the quality of life of patients after surgery. DVF is a critical pelvic floor fascia that is positioned anterior to the rectum. DVF may be regarded as a part of the mesorectum in the classic radical resection for rectal cancer and must be entirely excised to assure the radical resection of tumors. Meanwhile, DVF has a complex anatomical structure, whose intraoperative preservation elevates the complexity of the surgery. Hence, DVF preservation during radical resection for rectal cancer is now disputed in the clinic. Abroad, some researchers[28] discovered that the excised DVF tissues had many nerve fibers, including NOS-positive nerve fibers associated with erectile function, which were distributed more broadly and not limited to the previously described NVB region. Therefore, even in the "inverted U-shaped" resection of DVF, NVB preservation is futile, as the efferent branch of inferior hypogastric plexus may be injured, then compromising postoperative urine and sexual functions, particularly erectile function[29]. A prior study[30] utilized intraoperative nerve stimulation to identify PANs and unraveled that after DVF excision, nerve stimulation cannot elicit active bladder contraction, objectively validating the intimate association between DVF and PAN. Li et al[31] conducted a retrospective comparison study on the issue of DVF preservation or not in laparoscopic radical resection for low rectal cancer. The use of DVF in laparoscopic radical resection of low rectal cancer not only minimizes the amount of intraoperative bleeding, but also promotes the postoperative recovery of urine and sexual functions in patients and improves their quality of life. In addition, the research by Fang et al[32] exhibited that compared to standardized TME surgery, iTME can successfully minimize the incidence of postoperative urinary and sexual disorders in male patients with low rectal cancer without affecting the short-term radical outcome.

Conclusively, DVF, an influential separating and barrier structure surrounding the rectum, is of paramount significance to the quality of life and the protection of PANs following surgery for rectal cancer. Previously, the PUF-01 multicenter prospective study was performed on the impact of partial and complete preservation of DVF on the postoperative sexual and urinary function of patients with rectal cancer[24], which unraveled that the complete preservation of DVF exerted a protective effect on postoperative urogenital function as compared to the partial resection of DVF during laparoscopic TME. Nevertheless, long-term follow-up data are lacking for postoperative urogenital function in this group of patients both at home and abroad, precluding a more precise and detailed dynamic evaluation. In China, a tentative agreement has been achieved on the surgical treatment of DVF. According to the China Expert Consensus of iTME[4], iTME surgery can deliver short-term overall survival rates comparable to those of traditional TME surgery for male patients with middle and low rectal cancer at preoperative clinical stages of T1-4 (T1-2 for anterior wall tumor), N0-2, and M0 (7th editions of AJCC staging). According to this study, iTME can lower the incidence of postoperative micturition and sexual dysfunction in patients with rectum cancer at T1-4, N0-2, and M0 stages. However, existing evidence only supports individuals with tumors in the rectal anterior wall at T1-2, N0-2, and M0 stages. More importantly, PAN protection in radical resection for rectal cancer is a multi-step process that cannot be achieved by focusing only on a few important elements. As a result, further analysis of the entire pelvic structure is warranted to further optimize the membrane-guided PAN protection technology and maximize the benefits to patients from therapy.

We acknowledge and appreciate our colleagues for their valuable suggestions and funding assistance for this Minireviews.

| 1. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15628] [Article Influence: 2232.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 2. | Heald RJ, Husband EM, Ryall RD. The mesorectum in rectal cancer surgery--the clue to pelvic recurrence? Br J Surg. 1982;69:613-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1985] [Cited by in RCA: 1975] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Heald RJ, Ryall RD. Recurrence and survival after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Lancet. 1986;1:1479-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1867] [Cited by in RCA: 1937] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Minimally Invasive Anatomy Group; Colorectal Cancer Committee of Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Colorectal and Anal Function Surgeons Committee of China Sexology Association. [Chinese consensus on Denonvilliers' fascia preserving total mesorectal excision (iTME) (2021 version)]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2021;24:467-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wang YR. Effects of laparoscopic radical surgery of middle and low rectal cancer at the level of free anterior rectal wall on urination and sexual function in male patients. Gansu Yiyao. 2022;41:338-339+345. |

| 6. | Abdelrahman HGMW. Anatomical identification of transabdomin al TME endline and transanal TME initiation line and observation of perirectal fascial complex and neurovascular bundle. Doctoral thesis, Fujian Medical University, 2020. |

| 7. | Wang Y, Ma GL, Liang XB. Anatomic study of denonvilliers fascia and its application in rectal surgery. Zhongguo Linchuang Jiepouxue Zazhi. 2015;20:534-539. |

| 8. | Wei H, Wei B, Zheng Z. [Should Denonvilliers' fascia be preserved during laparoscopic radical surgery for rectal cancer? Value and feasibility of preserving Denonvilliers' fascia]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2015;18:773-776. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kim JH, Kinugasa Y, Hwang SE, Murakami G, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Cho BH. Denonvilliers' fascia revisited. Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37:187-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fang JF, Wei HB. Controversy and prospect of whether to remove Denonvilliers' fascia in radical rectal cancer. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2018;38:1124-1127. |

| 11. | Huang J, Liu J, Fang J, Zeng Z, Wei B, Chen T, Wei H. Identification of the surgical indication line for the Denonvilliers' fascia and its anatomy in patients with rectal cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2020;40:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Frizzell B, Lovato J, Foster J, Towers A, Lucas J, Able C. Impact of bladder volume on radiation dose to the rectum in the definitive treatment of prostate cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2015;13:288-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang JL, Zheng ZH, Wei HB, Fang JF, Zhang S, Chen YQ. A Comparative Study of Anatomy and Luminal Observation of Rectal Mesentery Structures. Zhongshan Daxue Xuebao Yixue Kexue Ban. 2014;3:407-411. |

| 14. | Muraoka K, Hinata N, Morizane S, Honda M, Sejima T, Murakami G, Tewari AK, Takenaka A. Site-dependent and interindividual variations in Denonvilliers' fascia: a histological study using donated elderly male cadavers. BMC Urol. 2015;15:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Deng XB, Meng WJ, Zhang YC, Jin CW, Yang TH, Wei MM, Shu Y, Wang ZQ, Zhou ZG. Layered structure of Denovilliers fascia in the anterior rectal hiatus and its relationship with prostatic vascular branches. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2013;16:489-493. |

| 16. | Zhu XM, Yu GY, Zheng NX, Liu HM, Gong HF, Lou Z, Zhang W. Review of Denonvilliers' fascia: the controversies and consensuses. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2020;8:343-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhang C, Ding ZH, Li GX, Huang XC, Zhong SZ. Biopsy of perirectal fascia and pelvic autonomic nerves associated with laparoscopic total mesorectal excision. Guangdong Yixue. 2012;16:2407-2410. |

| 18. | Lindsey I, Guy RJ, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ. Anatomy of Denonvilliers' fascia and pelvic nerves, impotence, and implications for the colorectal surgeon. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1288-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wei B, Huang SX, Gu XP, Liu J, Zou JT, Liu XH, Zhou DG, Huang JL, Zheng ZH, Wei HB. A study of the anatomy of the pelvic fascia and its relation to the intrinsic fascia of the rectum. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2021;41:768-773. |

| 20. | Liang ZP, Yang YG, Wu TT, Chen BJ, Zhang C. Fascial anatomy of retroperitoneal autonomic nerves associated with rectal cancer surgery. Zhongguo Linchuang Jiepouxue Zazhi. 2019;2:121-125. |

| 21. | Heald RJ, Moran BJ, Brown G, Daniels IR. Optimal total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer is by dissection in front of Denonvilliers' fascia. Br J Surg. 2004;91:121-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moszkowicz D, Alsaid B, Bessede T, Penna C, Nordlinger B, Benoît G, Peschaud F. Where does pelvic nerve injury occur during rectal surgery for cancer? Colorectal Dis. 2011;13:1326-1334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lu X, Guo JW, Liu XK, Wang YW, Zhao L, Li Y, He DQ, Ma JC, Ma Q, Song AL. Denonvilliers fascial dissection in laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery. Lanzhou Daxue Xuebao Yixue Ban. 2019;45:62-65. |

| 24. | Wei B, Zheng Z, Fang J, Xiao J, Han F, Huang M, Xu Q, Wang X, Hong C, Wang G, Ju Y, Su G, Deng H, Zhang J, Li J, Chen T, Huang Y, Huang J, Liu J, Yang X, Wei H; Chinese Postoperative Urogenital Function (PUF) Research Collaboration Group. Effect of Denonvilliers' Fascia Preservation Versus Resection During Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision on Postoperative Urogenital Function of Male Rectal Cancer Patients: Initial Results of Chinese PUF-01 Randomized Clinical Trial. Ann Surg. 2021;274:e473-e480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Deng Y, Chi P, Lan P, Wang L, Chen W, Cui L, Chen D, Cao J, Wei H, Peng X, Huang Z, Cai G, Zhao R, Xu L, Zhou H, Wei Y, Zhang H, Zheng J, Huang Y, Zhou Z, Cai Y, Kang L, Huang M, Wu X, Peng J, Ren D, Wang J. Neoadjuvant Modified FOLFOX6 With or Without Radiation Versus Fluorouracil Plus Radiation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer: Final Results of the Chinese FOWARC Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:3223-3233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 37.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Persiani R, Biondi A, Pennestrì F, Fico V, De Simone V, Tirelli F, Santullo F, D'Ugo D. Transanal Total Mesorectal Excision vs Laparoscopic Total Mesorectal Excision in the Treatment of Low and Middle Rectal Cancer: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:809-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chi P, Wang XJ. Significance and Technique of Denonvilliers' Fascia Dissection in Robotic and Laparoscopic Total Rectal Mesopexy. Zhongguo Shiyong Waike Zazhi. 2017;6:609-615. |

| 28. | Bertrand MM, Alsaid B, Droupy S, Benoit G, Prudhomme M. Biomechanical origin of the Denonvilliers' fascia. Surg Radiol Anat. 2014;36:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Liu J, Huang P, Liang Q, Yang X, Zheng Z, Wei H. Preservation of Denonvilliers' fascia for nerve-sparing laparoscopic total mesorectal excision: A neuro-histological study. Clin Anat. 2019;32:439-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Fang JF, Wei B, Zheng ZH, Chen TF, Huang Y, Huang JL, Lei PR, Wei HB. Effect of intra-operative autonomic nerve stimulation on pelvic nerve preservation during radical laparoscopic proctectomy. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:O268-O276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li Q, Gao B, Hou HP, Wang J. A controlled study with and without preservation of Denonvilliers' fascia in laparoscopic radical surgery for low rectal cancer. Zhonghua Putong Waike Zazhi. 2021;15:639-642. |

| 32. | Wei HB, Fang JF. [Total mesorectal excision with preservation of Denonvilliers' fascia (iTME) based on membrane anatomy]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;23:666-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Limaiem F, Tunisia; Wei HB, China S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yan JP