Published online Apr 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.341

Peer-review started: November 26, 2021

First decision: January 8, 2022

Revised: January 17, 2022

Accepted: March 27, 2022

Article in press: March 27, 2022

Published online: April 27, 2022

Processing time: 149 Days and 5.1 Hours

Despite being a benign disease, hepatolithiasis has a poor prognosis because of its intractable nature and frequent recurrence. Nonsurgical treatment is associated with high incidences of residual and recurrent stones. Consequently, surgery via hepatic lobectomy or segmental hepatectomy has become the main treatment modality. Clinical management and resolution of complicated hepatolithiasis with bilateral or diffuse intrahepatic stones remain very difficult and challenging. Repeated cholangitis and calculous obstruction may result in secondary biliary cirrhosis, a limiting factor in the treatment of hepatolithiasis.

A 53-year-old woman with a 5-year history of intermittent abdominal pain and fever was admitted to the hepatopancreatobiliary surgery department following worsening symptoms over a 3-d period. Blood tests revealed elevated transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and total bilirubin, as well as anemia. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed dilatation of the intrahepatic, left and right hepatic, common hepatic, and common bile ducts, and multiple short T2 signals in the intrahepatic and common bile ducts. Abdominal computed tomography showed splenomegaly and splenic varices. The diagnosis was bilateral hepatolithiasis and choledocholithiasis with cholangitis. Surgical treatment included hepatectomy of segments II and III, cholangioplasty, left hepaticolithotomy, second biliary duct exploration, choledo

Liver transplantation, rather than hepatectomy, might be a treatment option for complicated bilateral hepatolithiasis with secondary liver cirrhosis.

Core Tip: Treatment of complicated hepatolithiasis with bilateral intrahepatic stones is challenging. In this case of complicated hepatolithiasis with diffuse intrahepatic stones, liver imaging before surgery showed a normal morphology, but nodular and atrophic changes observed during segmental hepatectomy indicated cirrhosis. Preoperatively, the patient’s liver function was Child-Pugh class B, and the presence of splenomegaly indicated decompensated liver cirrhosis. Postoperatively, the patient experienced persisting elevated total bilirubin and worsened coagulation function. The patient ultimately experienced liver failure, respiratory failure, and septicemia resulting from severe biliary infection. Further treatment was discontinued at the family’s request.

- Citation: Fan WJ, Zou XJ. Subacute liver and respiratory failure after segmental hepatectomy for complicated hepatolithiasis with secondary biliary cirrhosis: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(4): 341-351

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i4/341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i4.341

Hepatolithiasis is defined by the presence of gallstones in all bile ducts peripheral to the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts, regardless of the coexistence of gallstones in other parts of the biliary tract[1]. It is prevalent primarily in Southeast Asia and in the southeastern coastal regions of China[2]. Obstruction caused by stones can lead to serious complications, including bile duct inflammation, liver cirrhosis, liver atrophy, or malignant transformation, and these contribute to hepatolithiasis being the most common cause of death among the nonmalignant diseases of the biliary tract[3]. As such, aggressive treatment is needed for all cases.

Although nonsurgical techniques are effective in resolving cholestasis and providing temporary relief (via removal) of stones, they cannot completely clear a sclerotic hepatobiliary system and may predispose the patient to subsequent recurrence. Hepatectomy has become a primary treatment for hepatolithiasis, applied most often to unilobar, particularly left-sided, hepatolithiasis[4]. Despite recent improvements in surgical and nonsurgical management of hepatolithiasis, difficulties remain in the treatment of complicated hepatolithiasis with bilateral stones. Surgery is still the mainstay of the treatment for complex hepatolithiasis cases. However, secondary biliary cirrhosis develops in 6.0%-7.4% of patients, and more than half experience moderate to severe Child-Pugh class B or C liver dysfunction[5]. The secondary biliary cirrhosis itself may further complicate treatment of the underlying hepatolithiasis. Herein, we present a patient with complicated bilateral hepatolithiasis and secondary biliary cirrhosis who failed treatment after undergoing segmental hepatectomy.

On July 30, 2021, a 53-year-old woman presented at the hepatopancreatobiliary surgery department of our hospital, complaining of intermittent abdominal pain with fever that she had experienced for 5 years but which had worsened over the previous 3 d.

The patient reported having developed intermittent abdominal pain with fever 5 years previously, describing the symptoms as having appeared every 2 or 3 mo over that time. She denied nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea during that time. In the immediate 3 d before her admission to our department, her symptoms had worsened, presenting with hyperpyrexia and chills that were accompanied by jaundice.

The patient had undergone a cholecystectomy 8 years prior. She had no history of other chronic diseases.

The patient had no history of smoking or drinking. She denied a history of allergies and her family history was unremarkable.

At admission, the patient’s temperature was 39.0 °C, heart rate was 104 beats per min, respiratory rate was 21 breaths per min, and blood pressure was 117/85 mmHg. She had a yellow coloration to her overall skin and sclera. Abdominal examination revealed tenderness in the right quadrant, without rebound tenderness. Lung and heart examinations were normal.

Blood workup in anticipation of surgical intervention revealed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count (4.01 × 109 cells/L), moderate anemia (hemoglobin of 80.0 g/L; normal range: 115.0-150.0 g/L), hypoproteinemia (25.3 g/L; normal range: 35.0-52.0 g/L), and elevated levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (39 U/L; normal range: ≤ 33 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (141 U/L; normal range: ≤ 32 U/L), total bilirubin (TBIL) (185.4 μmol/L; normal range: ≤ 21 μmol/L), direct bilirubin (DBIL) (146.3 μmol/L; normal range: ≤ 8 μmol/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (162 U/L; normal range: 35-102 U/L), and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) (135 U/L; normal range: 6-42 U/L). The coagulation markers were within normal range [prothrombin time (PT), 13.6 s; normal range: 11.5-14.5 s] and tests for hepatitis B and C were negative. The patient’s Child-Pugh score was 7, indicating class B. Six days after surgery (August 12, 2021), her TBIL reached a peak of 357 μmol/L; her DBIL was 255.5 μmol/L, ALP was 167 U/L, and γ-GT was 47 U/L. Eight days after surgery (August 14, 2021), arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.410, PaO2 of 66.3 mmHg, and PaCO2 of 43.9 mmHg, indicating acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ten days after surgery (August 16, 2021), the WBC count reached a peak of 29.81 × 109/L, with 90.7% of neutrophils, and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (103.7 mg/L; normal range: < 1 mg/L) was detected. Sixteen days after surgery (August 22, 2021), PT reached a peak of 19.5 s; her prothrombin activity (PTA) (normal range: 75.0%-125.0%) was 51%, international normalized ratio (INR) (normal range: 0.80-1.20) was 1.69, and activated partial thromboplastin time was 23.7 s (normal range: 29.0-42.0 s). Autoimmune hepatitis-associated antibody tests were negative for anti-mitochondrial antibody and weakly positive for anti-soluble liver antigen antibody. T-tube drainage fluid was Rivalta (+), with a karyocyte count of 1600 × 106 cells/L and neutrophil percentage of 62%. Twenty-five days after surgery (August 31, 2021), her blood ammonia level peaked, at 70 µmol/L.

Eleven days after surgery (August 17, 2021), the T-tube drainage fluid and subcutaneous drainage fluid cultures tested positive for Enterococcus faecalis and Candida parapsilosis; sputum cultures were also positive for Candida parapsilosis. Eighteen days after surgery (August 24, 2021), cultures of sputum and catheter fluid (sensitive to piperacillin/tazobactam and amikacin) and blood (sensitive to piperacillin/ tazobactam and cefepime) were positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

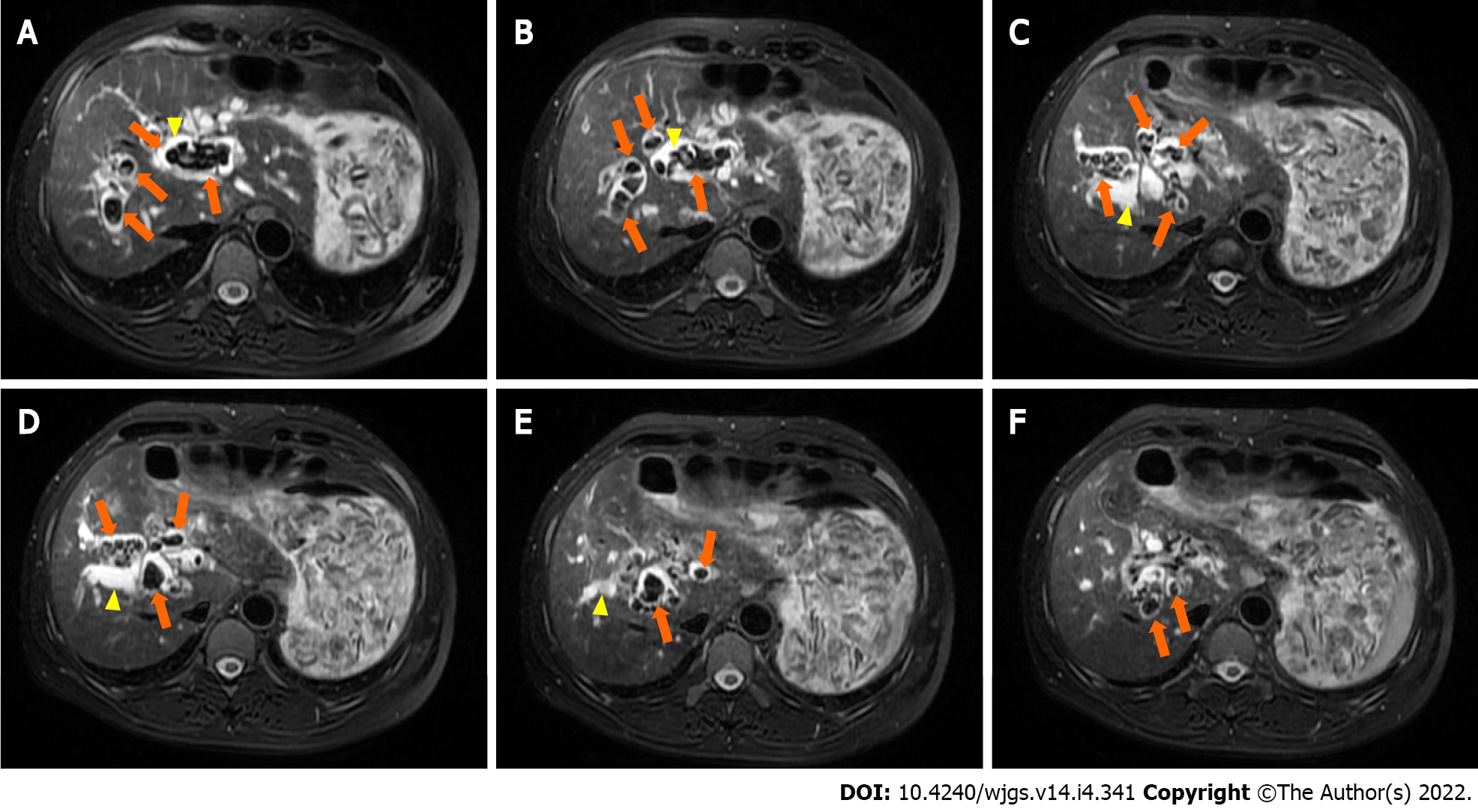

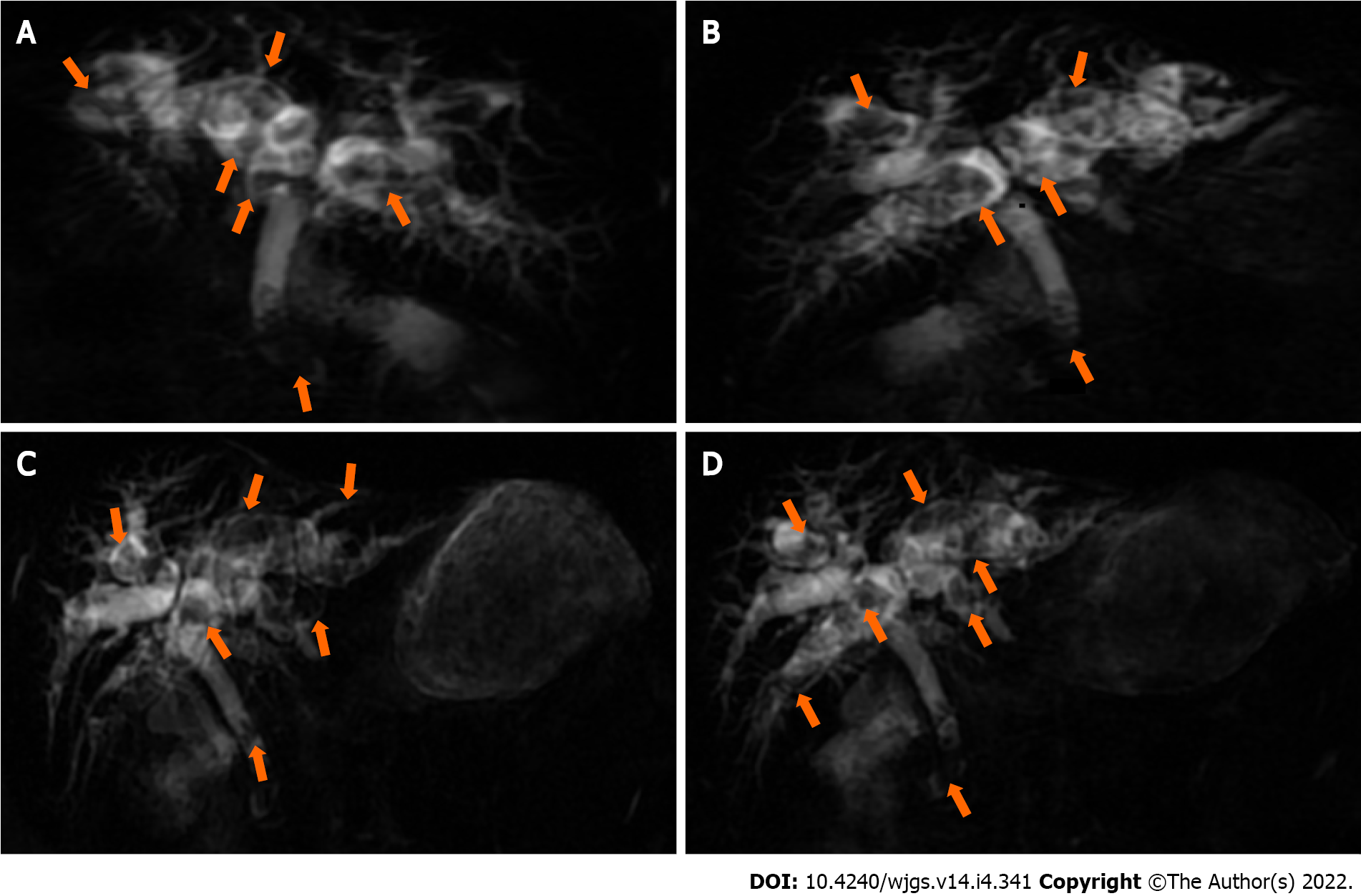

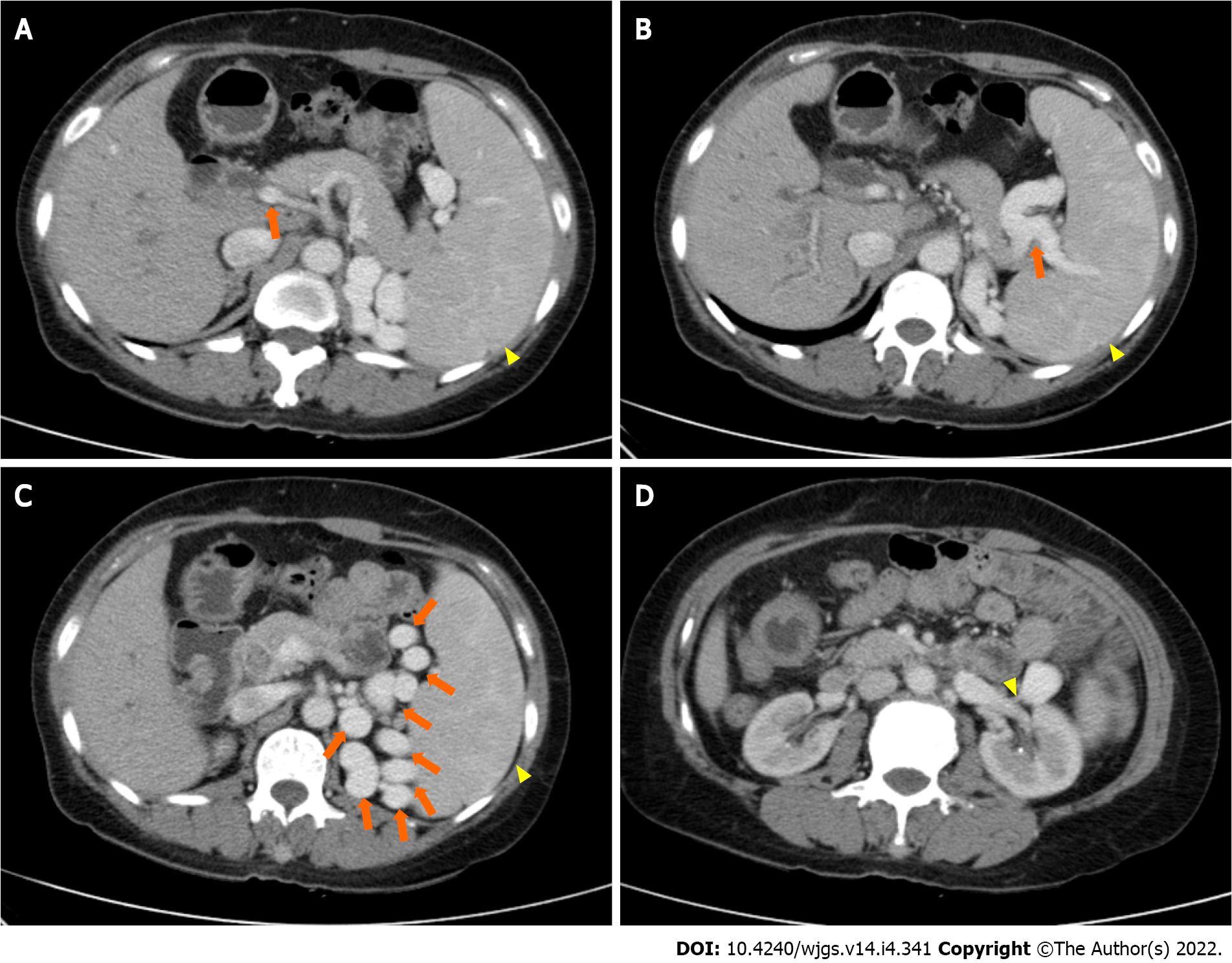

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography in anticipation of surgical intervention showed normal liver volume and left-to-right lobe proportion but splenomegaly and splenic varices. The gallbladder (removed 8 years prior) was absent from the imaging view, and the pancreas appeared normal. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed dilatation of the intrahepatic, left and right hepatic, common hepatic, and common bile ducts, and multiple short T2 signals in the intrahepatic and common bile ducts. Figure 1 shows the intrahepatic duct dilatation and multiple short T2 signals in the intrahepatic duct, which indicated multiple stones. Multiplanar reconstruction also showed multiple short T2 signals in the intrahepatic and common bile ducts (Figure 2). Abdominal and pelvic contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed multiple nodular high-density shadows in the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, with the largest ones up to 8 mm in length. Contrast-enhanced CT also showed intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts dilatation, portal vein narrowing, splenomegaly (Figure 3A), splenic varices (Figure 3B), collateral circulation expansion (Figure 3C), and spontaneous spleno-renal shunting (Figure 3D).

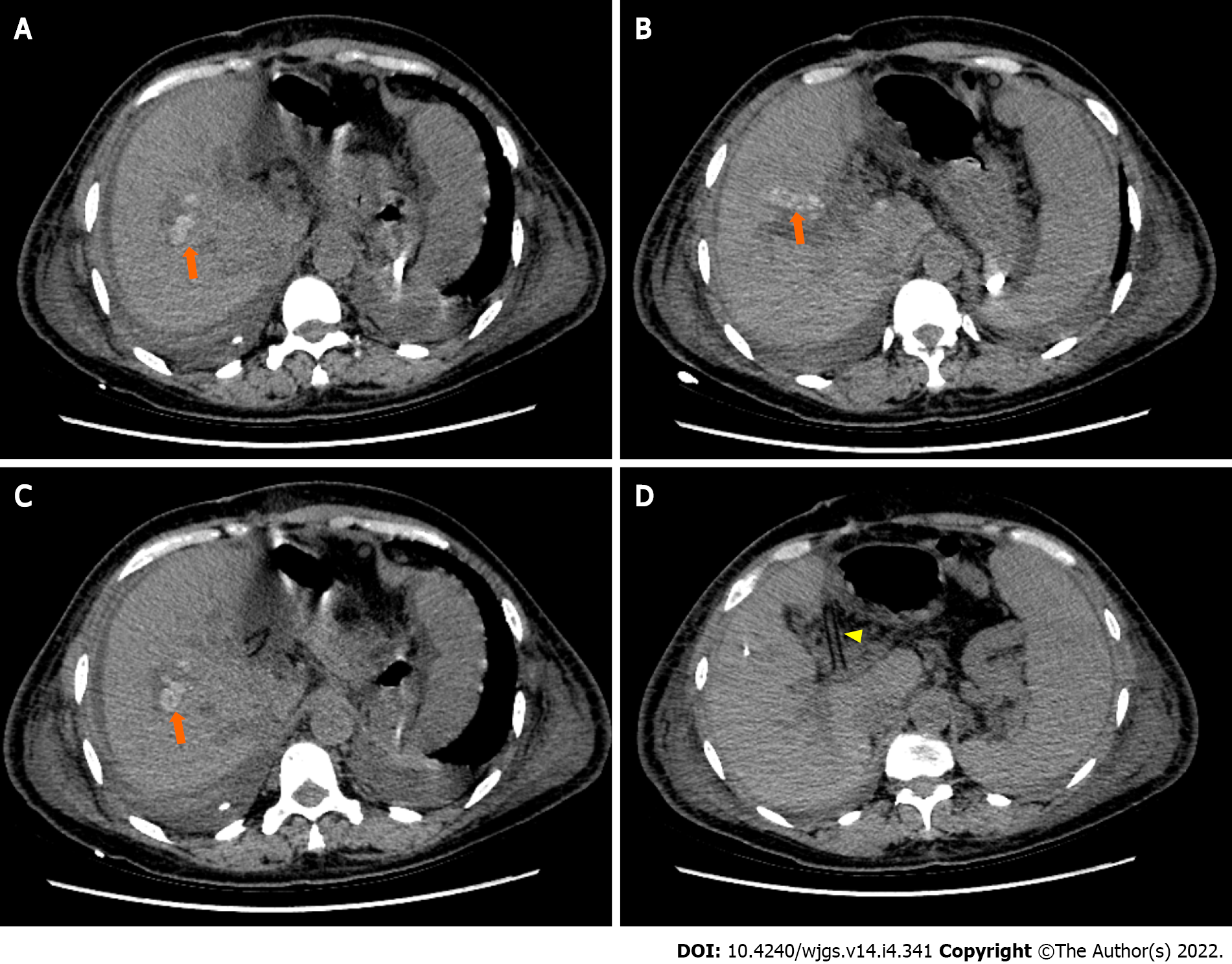

At day 6 postoperatively (August 12, 2021), abdominal CT showed multiple nodular high-density shadows in the right hepatic and common bile ducts with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation (Figure 4). Eight days after surgery (August 14, 2021), a bedside chest X-ray showed bilateral pulmonary diffuse patchy high-density shadows and bilateral pleural effusion, which indicated bilateral pulmonary infection (Figure 5A). Fourteen days after surgery (August 20, 2021), chest CT showed bilateral pulmonary nodular and patchy shadows and left pulmonary atelectasis, indicating pulmonary infection (Figure 5B–D). Pathology findings following evaluation of a 13 cm × 6.5 cm × 5 cm liver specimen included dilatation of multiple intrahepatic ducts, with a maximum diameter of 2 cm and containing multiple, brown stones. Histopathology included intrahepatic duct dilatation with stones and inflammatory cell infiltration of the bile duct walls (Figure 6). Proliferation of fibrous tissue in portal tracts divided the liver parenchyma into irregular regenerative nodules (pseudolobules) that had lost the normal architecture and central veins (Figure 7A–C). Hepatic cords were poorly arranged in foci, with two layers of cells and enlarged cells that included binucleate forms (Figure 7D–F).

The systemic infection is severe, the current anti-infective treatments are effective, and respiratory support therapy should be continued.

The patient’s TBIL has not declined with treatment and the pulmonary infection is severe, indicating a poor prognosis. Sputum, catheter, and blood cultures are positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, indicating hematogenous spread. The catheter should be replaced. If the infection cannot be controlled, fosfomycin can be added. The persisting elevated TBIL is related to surgery, biliary tract infection, and obstruction. Percutaneous transhepatic cholangial drainage may be useful.

The T-tube is open and the current drug treatments should be continued. There is no indication for a second surgery.

Bilateral hepatolithiasis and choledocholithiasis with cholangitis (after partial hepatectomy), subacute liver failure, secondary biliary cirrhosis, splenomegaly, splenic varices, type 1 respiratory failure, severe pneumonia, septicemia (Pseudomonas aeruginosa), abdominal infection, anemia, and hypoproteinemia.

After admission, polyene phosphatidylcholine (465 mg), ademetionine 1,4-butanedisulfonate (1 g), and glycine cysteine sodium chloride (200 mL) were given once a day (QD) as liver-protective therapy. Ceftriaxone sodium and tazobactam sodium (2 g) were given two times a day (BID) for 3 d as anti-infective treatment. On August 6, 2021, hepatectomy of segments II and III, cholangioplasty, left hepaticolithotomy, second biliary duct exploration, choledocholithotomy, T-tube drainage, and accretion lysis were performed. During surgery, stones were palpable in the common bile duct and left lateral lobe of the liver. The liver showed nodular and atrophic changes, which indicated cirrhosis. After surgery, hepatocyte growth-promoting factor (60 μg), acetylcysteine (8 g), and reduced glutathione (1.8 g) were given QD for liver protection. Ambroxol hydrochloride (60 mg) and doxofylline (0.3 g) were given BID to promote expectoration drainage. Imipenem and cilastatin sodium [0.5 g every 8 h (q8h)] and linezolid and glucose [0.6 g every 12 h (q12h)] were given as anti-infective treatment from August 7-10, 2021 and were then switched to meropenem (1 g) and tigecycline (50 mg q8h) from August 11-13, 2021.

On August 10, 2021, the patient developed dyspnea, decreased oxygen saturation, and a continuously increasing level of TBIL. Considering pulmonary infection and liver failure, the patient was transferred to the infectious disease department on August 13, 2021. The anti-infective treatments were changed to meropenem (1 g q8h), teicoplanin (400 mg QD), and voriconazole (0.2 g q12h). On August 14, 2021, the patient developed tachypnea with bilateral moist rales. The arterial PaO2 dropped to 66.3 mmHg and the PaCO2 increased to 43.9 mmHg. Tracheal intubation was performed, and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). A single dose of methylprednisolone (40 mg) was given, and fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed to aspirate sputum. In the ICU, anti-infective treatment included meropenem (1 g q8h) given from August 15-17, 2021, imipenem and cilastatin sodium (0.5 g q8h) given from August 17-22, 2021, piperacillin sodium and tazobactam sodium (4.5 g q6h) given from August 24-28, 2021, amikacin (0.4 g q12h) given from August 24-29, 2021, ceftazidime (1 g q8h) given from August 28 to September 1, 2021, polymyxin B sulfate (75 wu q12h) given from August 29 to September 1, 2021, tigecycline (50 mg q8h) given from August 15 to 23, 2021, vancocin (1000 mg BID) given from August 22 to 30, 2021, voriconazole (0.2 g q12h) given from August 18 to 24, 2021, and micafungin sodium (100 mg QD) given from August 24 to September 1, 2021. Ventilator support was provided, and the patient was given packed red blood cell and fresh frozen plasma transfusions; noradrenaline bitartrate was given to maintain blood pressure.

On August 25, 2021, the patient was successfully extubated and given high flow nasal oxygen. On August 26, 2021, artificial liver support therapy and plasmapheresis were performed. On August 27, 2021, the patient was reintubated because of disturbance of consciousness and decreased oxygen saturation.

Sputum, catheter fluid, and blood cultures were positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The patient’s TBIL continued to increase after surgery and her coagulation function worsened. Her family elected to discontinue treatment because of severe infection, septicemia, and liver and respiratory failure.

Hepatolithiasis is a disease of unknown etiology that seriously impacts patient health and quality of life, with a reported morbidity of 20%–50% in patients who undergo cholecystectomy[6]. Our patient had undergone cholecystectomy 8 years prior to presentation at our department. Since her autoimmune hepatitis-associated antibodies were not sufficiently elevated to support a diagnosis of autoimmune liver disease, we hypothesize that the etiology of her presenting hepatolithiasis may have been related to her history of cholecystectomy.

Complete stone clearance, restoration of normal bile flow, and excision of diseased hepatic parenchyma are the goals of hepatolithiasis treatment. In the last decade, advances in nonsurgical and surgical treatments have resulted in improvement of the management of the disease, but such nonsurgical treatments as percutaneous transhepatic and peroral cholangioscopic lithotripsy are associated with high rates of residual and recurrent stones[7]. Hepatectomy, mainly segmental hepatectomy, is an effective surgical treatment that can remove stones, diseased bile ducts, and damaged hepatic parenchyma[8]. However, hepatectomy is applied most often to cases of unilobar, particularly left-sided, hepatolithiasis[4]. Hepatolithiasis involving two or more lobes is challenging because diffuse intrahepatic stones in bilateral intrahepatic ducts are difficult to clear, strictures may be present in the remaining liver, and calculus extraction may be incomplete. Hepatectomy for bilateral hepatolithiasis is controversial, as patients may not tolerate resection of multiple liver segments. Therefore, bile duct exploration and choledochoscopic lithotomy combined with a reduced hepatectomy were essential. Some studies have reported resection of the dominantly-affected side, followed by postoperative cholangioscopic lithotomy[9]. Right hepatic lobectomy is usually avoided because of the increased risk involved. Our patient was treated with a left-sided segmental hepatectomy, and stones remaining in the right hepatic duct after surgery can be seen in Figure 4. Bilateral hepatolithiasis deserves to be considered as a distinct disease.

Although imaging evaluation showed that the patient’s liver morphology was relatively normal, splenomegaly and splenic varices indirectly indicated portal hypertension. The surgical and pathological findings confirmed secondary biliary cirrhosis. Established liver cirrhosis has been reported in 10%–15% of patients with hepatolithiasis at the initial presentation[10], and secondary biliary cirrhosis has been reported to develop 7 years after the onset of obstruction and 4.5 years after a calculous obstruction[11]. Our patient had intermittent abdominal pain with fever for 5 years and her liver function on admission was Child-Pugh class B (i.e. decompensated liver cirrhosis), which was consistent with the reported prognosis. Patients with secondary biliary cirrhosis may be prone to postoperative sepsis and at increased risk of postprocedural complications. Previous studies have reported that 10%–30% of patients with cirrhosis developed bacterial infections after abdominal surgery[12], which may have been related to impaired immune defense mechanisms of the liver. As the prognosis is better and the feasibility of aggressive management is greater in patients with Child-Pugh class A than class B or C status, we believe that hepatolithiasis should be managed early, before the development of secondary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatolithiasis combined with secondary biliary cirrhosis was frequently found and we have to pay attention and try to prevent the occurrence of hepatic failure after surgery especially in the jaundiced patient.

There are no widely accepted guidelines for treating patients with terminal hepatolithiasis. According to the classification described by Feng et al[13], our patient had Type IIc disease with diffuse stones, biliary cirrhosis, and portal hypertension. Liver transplantation is recommended for such patients[13]. The indications for liver transplantation include end-stage decompensated liver cirrhosis and/or liver failure, compensated cirrhosis or non-cirrhosis in patients with diffusely distributed intrahepatic calculi, and/or multiple hepatobiliary stenoses that cannot be cured by other surgical and nonsurgical procedures[14]. Our patient was suitable for liver transplantation, which has a reported 1-year survival of 100% and 5-year survival of 73%[15]. However, because of the critical shortage of cadaveric livers, grafts are preferentially provided to those with the highest likelihood of death without transplantation. Owing to the limited understanding of patients and doctors about liver transplantation for hepatolithiasis, few patients have received liver transplants[15]. Terminal hepatolithiasis, especially when combined with portal hypertension and previous right upper quadrant surgery, may make the transplantation procedure difficult. Thus, selecting patients for transplantation before they reach end-stage disease is important. However, the imaging before surgery did not show signs of liver cirrhosis and it was until the surgery that surgeons found that the liver showed nodular and atrophic changes indicating cirrhosis. Besides, in China, liver transplantation was mostly for end-stage liver cirrhosis and it was not easy to get access to liver donors since the patient’s general conditions were relatively good compared to patients with end-stage liver cirrhosis. Therefore, the surgeons did not discuss liver transplantation with the patient before surgery.

Surgery failed to rescue our patient. One of the reasons was infection. The patient suffered from abdominal infection derived from bile duct and pulmonary infection, resulting in respiratory failure and septicemia. The primary cause of death after hepatectomy is reported to be uncontrollable septicemia[7], and positive bile cultures have been reported in 83.3% of patients with hepatolithiasis[12], which is higher than the incidence of surgical site infections after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma[12]. Sepsis must thus be effectively controlled before hepatectomy in patients with hepatolithiasis. Another reason for patient death is liver failure. The maximum TBIL of our patient was 10-times higher than the upper limit of normal and her maximum INR was 1.69. The guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure suggest that patients with a TBIL level of more than 10-times normal and a PTA ≤ 40% or an INR ≥ 1.5 can be diagnosed with liver failure[16]. The reasons for liver failure in our patient were related to liver resection and the abnormal function of the remaining liver.

The management of complicated bilateral hepatolithiasis is challenging, and segmental hepatectomy is unable to completely remove all the intrahepatic ductal stones. It is important to effectively control biliary tract infection before surgical procedures. Liver transplantation rather than hepatectomy may be considered as an option in complicated bilateral hepatolithiasis with secondary liver cirrhosis.

| 1. | Liu B, Cao PK, Wang YZ, Wang WJ, Tian SL, Hertzanu Y, Li YL. Modified percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation for patients with refractory hepatolithiasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:3929-3937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kim HJ, Kim JS, Joo MK, Lee BJ, Kim JH, Yeon JE, Park JJ, Byun KS, Bak YT. Hepatolithiasis and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:13418-13431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Cheon YK, Cho YD, Moon JH, Lee JS, Shim CS. Evaluation of long-term results and recurrent factors after operative and nonoperative treatment for hepatolithiasis. Surgery. 2009;146:843-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Nuzzo G, Clemente G, Giovannini I, De Rose AM, Vellone M, Sarno G, Marchi D, Giuliante F. Liver resection for primary intrahepatic stones: a single-center experience. Arch Surg. 2008;143:570-3; discussion 574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | You MS, Lee SH, Kang J, Choi YH, Choi JH, Shin BS, Huh G, Paik WH, Ryu JK, Kim YT, Jang DK, Lee JK. Natural Course and Risk of Cholangiocarcinoma in Patients with Recurrent Pyogenic Cholangitis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Gut Liver. 2019;13:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Catena M, Aldrighetti L, Finazzi R, Arzu G, Arru M, Pulitanò C, Ferla G. Treatment of non-endemic hepatolithiasis in a Western country. The role of hepatic resection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:383-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jan YY, Chen MF, Wang CS, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Chen SC. Surgical treatment of hepatolithiasis: long-term results. Surgery. 1996;120:509-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Qiao O, Hu P, Jin Y. Hepatic lobectomy and segmental resection of liver for hepatolithiasis. West Indian Med J. 2014;63:176-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Uenishi T, Hamba H, Takemura S, Oba K, Ogawa M, Yamamoto T, Tanaka S, Kubo S. Outcomes of hepatic resection for hepatolithiasis. Am J Surg. 2009;198:199-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Strong RW, Chew SP, Wall DR, Fawcett J, Lynch SV. Liver transplantation for hepatolithiasis. Asian J Surg. 2002;25:180-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Scheuer PJ. Biliary disease and cholestasis. In: Scheuer PJ, editor. Liver biopsy interpretation. 4th ed. London: Baillere Tindall, 1988: 40-65. |

| 12. | Uchiyama K, Ueno M, Ozawa S, Kiriyama S, Kawai M, Hirono S, Tani M, Yamaue H. Risk factors for postoperative infectious complications after hepatectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:67-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Feng X, Zheng S, Xia F, Ma K, Wang S, Bie P, Dong J. Classification and management of hepatolithiasis: A high-volume, single-center's experience. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2012;1:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Ali JM, See TC, Wiseman O, Griffiths WJ, Jah A. Salvage of liver transplant with hepatolithiasis by percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic hepatolithotomy. Transpl Int. 2014;27:e126-e128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen ZY, Yan LN, Zeng Y, Wen TF, Li B, Zhao JC, Wang WT, Yang JY, Xu MQ, Ma YK, Wu H. Preliminary experience with indications for liver transplantation for hepatolithiasis. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3517-3522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Liver Failure and Artificial Liver Group Group, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association; Severe Liver Disease and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association; Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association; Severe Liver Disease and Artificial Liver Group, Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. [Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2019;27:18-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kanno H, Japan; Ker CG, Taiwan; Mansilla-Vivar R, Chile S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Fan JR