Published online Dec 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i12.1340

Peer-review started: August 28, 2022

First decision: September 12, 2022

Revised: September 26, 2022

Accepted: November 20, 2022

Article in press: November 20, 2022

Published online: December 27, 2022

Processing time: 120 Days and 17.7 Hours

Bacterial infection is an important cause of cholelithiasis or gallstones and interferes with its treatment. There is no consensus on bile microbial culture profiles in previous studies, and identified microbial spectrum and drug resistance is helpful for targeted preventive and therapeutic drugs in the perioperative period.

To analyze the bile microbial spectrum of patients with cholelithiasis and the drug susceptibility patterns in order to establish an empirical antibiotic treatment for cholelithiasis-associated infection.

A retrospective single-center study was conducted on patients diagnosed with cholelithiasis between May 2013 and December 2018.

This study included 185 patients, of whom 163 (88.1%) were diagnosed with gallstones and 22 (11.9%) were diagnosed with gallstones and common bile duct stones (CBDSs). Bile culture in 38 cases (20.5%) was positive. The presence of CBDSs (OR = 5.4, 95%CI: 1.3-21.9, P = 0.03) and longer operation time (> 80 min) (OR = 4.3, 95%CI: 1.4-13.1, P = 0.01) were identified as independent risk factors for positive bile culture. Gram-negative bacteria were detected in 28 positive bile specimens, and Escherichia coli (E. coli) (19/28) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (5/28) were the most frequently identified species. Gram-positive bacteria were present in 10 specimens. The resistance rate to cephalosporin in E. coli was above 42% and varied across generations. All the isolated E. coli strains were sensitive to carbapenems, with the exception of one imipenem-resistant strain. K. pneumoniae showed a similar resistance spectrum to E. coli. Enterococcus spp. was largely sensitive to glycopeptides and penicillin, except for a few strains of E. faecium.

The presence of common bile duct stones and longer operation time were identified as independent risk factors for positive bile culture in patients with cholelithiasis. The most commonly detected bacterium was E. coli. The combination of β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors prescribed perioperatively appears to be effective against bile pathogens and is recommended. Additionally, regular monitoring of emerging resistance patterns is required in the future.

Core Tip: In this work, we analyzed the microbial spectrum of the bile of cholelithiasis patients, and their drug susceptibility pattern. We found that the presence of common bile duct stones and longer operative duration were independent risk factors for positive bile culture for patients complicated with cholelithiasis. The most commonly detected bacterium was Escherichia coli. In addition, the combination of β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors prescribed perioperatively appears to be effective against bile pathogens secondary to carbapenems or glycopeptides and is recommended, but its resistance should also be noted.

- Citation: Huang XM, Zhang ZJ, Zhang NR, Yu JD, Qian XJ, Zhuo XH, Huang JY, Pan WD, Wan YL. Microbial spectrum and drug resistance of pathogens cultured from gallbladder bile specimens of patients with cholelithiasis: A single-center retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(12): 1340-1349

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i12/1340.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i12.1340

Bacteria can easily enter the biliary system from the duodenum; however, continuous bile secretion in the biliary system prevents their growth and colonization. Despite this, the presence of bacteria in bile has been reported in 9.5%-54.0% of patients with cholelithiasis or gallstones[1-3], and up to 70.2%-78.0% of patients with common bile duct stones (CBDSs)[4,5]. As the presence of bacteria in the biliary tract may increase the risk of postoperative septic complications[6-8], it is essential to identify the risk factors for positive bile culture during cholecystectomy and, accordingly, design a suitable antibiotic prophylaxis regimen[6,8].

The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in the last few decades has led to the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) pathogenic bacteria[9], which have also been isolated from bile specimens[10]. Such MDR microbes reduce the efficacy of empirical drugs[11,12]. Therefore, it is essential to identify the species of pathogenic bacteria found in the bile of cholelithiasis patients, as well as their drug susceptibility profile, in order to develop effective antibiotic regimens for biliary tract infections. To this end, we analyzed the distribution and drug resistance patterns of pathogens isolated from bile samples obtained from patients with cholelithiasis on the basis of bile culture and drug susceptibility test results.

This study included patients with bile culture results who underwent cholecystectomy with or without common bile duct exploration, stone extraction, and T tube drainage between May 2013 and December 2018 at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery at The Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. The indications for surgical treatment were cholelithiasis and its complications. Most patients had presented with right upper abdominal pain or other discomfort at the time of admission. In all the included patients, a gallstone with acute or chronic cholecystitis was preoperatively diagnosed based on abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) imaging and confirmed after cholecystectomy. Each surgical procedure was performed by a professional hepatobiliary surgical team. Access to clinical data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (2022ZSLYEC-352).

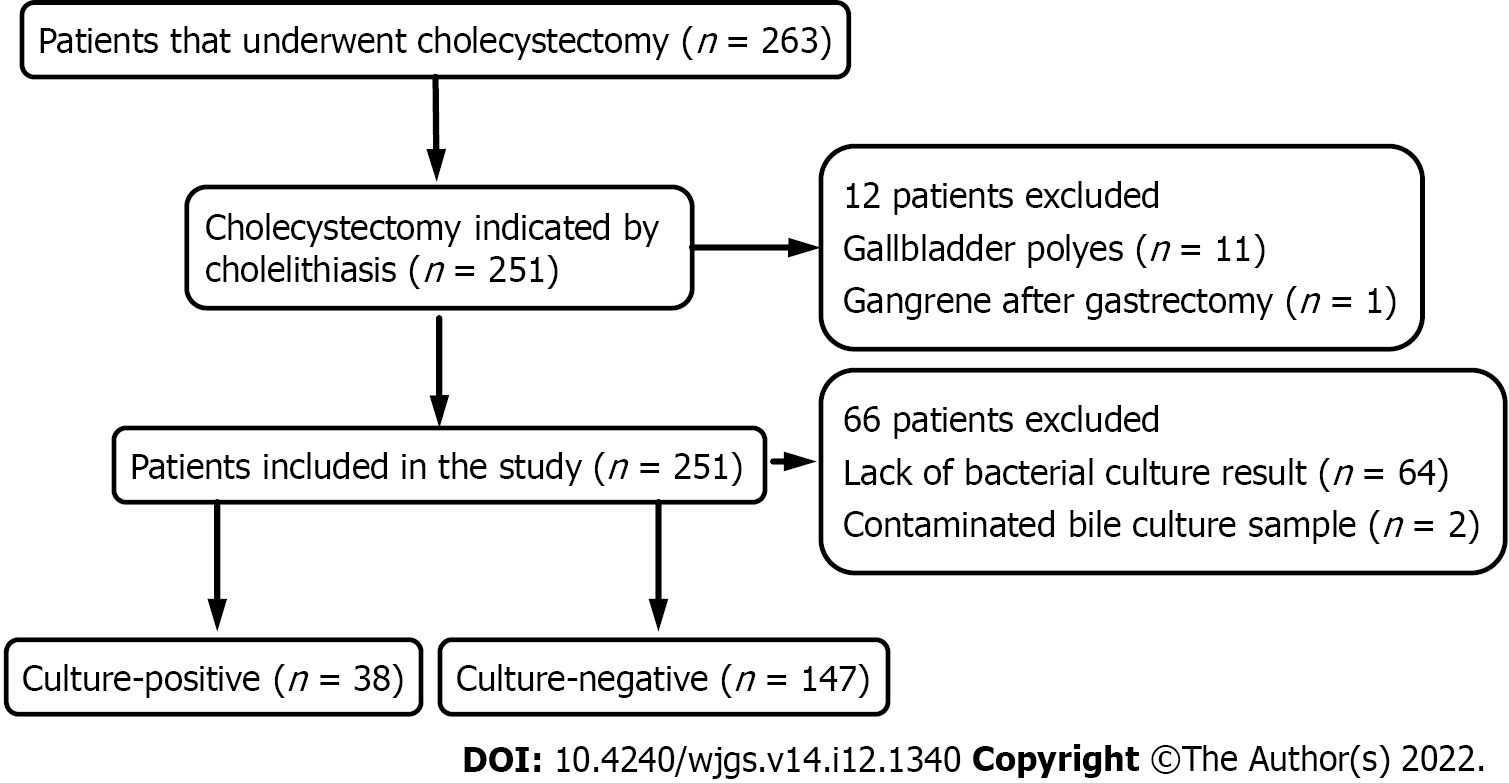

Inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥ 18 years, who underwent cholecystectomy indicated by cholelithiasis and its complications. All included patients had complete clinicopathological and bile culture results. Exclusion criteria were cholecystectomy indicated by other reasons (n = 12), lack of bacterial culture results (n = 64), and contaminated bile culture sample (n = 2). Demographic characteristics, microbial spectrum and drug resistance of pathogens in patients were assessed. A total of 185 patients were included, and the clinicopathological and microbiological data were retrospectively collected from the medical record system. The research flow chart is outlined in Figure 1.

Bile samples (5 µL) were extracted during cholecystectomy and promptly transported in sterile containers to a microbiology laboratory for bacterial culture as per standard protocols. Bacterial identification and drug susceptibility tests were performed using the French Bio-Merieux ATB-Expression Automatic Bacterial Identification and Drug Susceptibility Test instrument. The results were evaluated according to the 2010 recommendations of the American Society for Clinical Laboratory Standardization.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 24.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous variables that followed Gaussian distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, and those with non-normal distribution were expressed as the median with interquartile range. Categorical variables were described using frequencies. Data were compared using the two-tailed student t-test, chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Mann-Whitney U-test, as appropriate. Significant covariates identified by univariate analysis were further analyzed by multivariate logistic regression analysis to determine the independent risk factors for positive bile culture. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Out of a total of 285 patients who underwent cholecystectomy between May 2013 and December 2018, 185 fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in this study. The cohort comprised 80 (43.2%) male and 105 (56.8%) female patients, and their mean age was 54.3 years (SD = 15). Twenty-two patients were diagnosed with gallstones accompanied by CBDSs, and bile cultures were positive for 17 (77.3%) of these patients. In contrast, only 12.9% (21/163) of the patients who did not have CBDSs had bacterial colonization in their bile samples. In addition, 155 (83.8%) patients had right upper abdominal discomfort. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the most common procedure used for removing gallstones, but four patients with calculous cholecystitis underwent open surgery due to severe adhesions. In addition, one patient with CBDSs underwent complete laparoscopic surgery. The median operative time was 80 (59-120) min, and cefotaxime/sulbactam sodium and cefamandole were the main preventive or therapeutic antibiotics used preoperatively. The overall rate of septic complications was 5.4% (10/185), and the incidence of septic complications was similar in the culture-positive and culture-negative patients [4.1% (6/147) vs 10.5% (4/38)]. The detailed demographic characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1, and they show significant differences in age, BMI, presence of CBDSs, previous endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), previous use of antibiotics, presence of multiple stones, open surgery, operation time, and preoperative therapeutic antibiotics. Multivariate logistic regression analysis of these significant variables indicated that the presence of CBDSs (OR = 5.4, 95%CI: 1.8-21.9, P = 0.029) and longer operation time (OR = 4.3, 95%CI: 1.4-13.1, P = 0.01) were independent risk factors for bacterial colonization of bile samples (Table 2).

| Parameter | Total | Culture-negative | Culture-positive | P value |

| Number | 185 | 147 | 38 | - |

| Age (yr; mean ± SD) | 54.3 ± 15.0 | 52.4 ± 14.7 | 61.3 ± 14.2 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2; mean ± SD) | 23.1 ± 3.4 | 23.4 ± 3.2 | 22.1 ± 3.8 | 0.040 |

| Male (%) | 80 (43.2) | 61 (33.0) | 19 (10.3) | 0.346 |

| Combined with CBDS (%) | 22 (11.9) | 5 (2.7) | 17 (9.2) | < 0.001 |

| Right upper abdominal pain (%) | 155 (83.8) | 120 (64.9) | 35 (18.9) | 0.118 |

| Positive Murphy sign (%) | 27 (14.6) | 24 (13.0) | 3 (1.6) | 0.189 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 11 (5.9) | 8 (4.3) | 3 (1.6) | 0.699 |

| Hypertension (%) | 41 (22.2) | 32 (17.3) | 9 (4.9) | 0.800 |

| History of ERCP (%) | 7 (3.7) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (3.2) | < 0.001 |

| Previous intake of antibiotics (%) | 44 (23.8) | 29 (15.7) | 15 (8.1) | 0.011 |

| WBC count (> 10 × 109/L) | 16 (8.6) | 11 (5.9) | 5 (2.7) | 0.267 |

| Multiple stones (%) | 132 (71.3) | 99 (53.5) | 33 (17.8) | 0.018 |

| Max diameter of stone (cm; mean ± SD) | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 0.177 |

| Non-laparoscopic surgery (%) | 41 (22.2) | 19 (10.3) | 22 (11.9) | < 0.001 |

| Operative time (min), median (IQR) | 80 (59-120) | 70 (56.5-93.8) | 124 (95.0-188.8) | < 0.001 |

| Septic complications (%) | 10 (5.4) | 6 (3.2) | 4 (2.2) | 0.125 |

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | P |

| Operation time > 80 min | 4.3 (1.4-13.1) | 0.01 |

| Combined with CBDS | 5.4 (1.3-21.9) | 0.02 |

Of the 38 (20.5%) patients with positive bile culture results, 28 (73.7%) harbored gram-negative bacteria that were predominantly from the family Enterobacteriaceae, including Escherichia coli (19 cases), Klebsiella pneumoniae (5 cases), Enterobacter cloacae (2 cases), Enterobacter aerogenes (1 case), and Enterobacter mirabilis (1 case). Gram-positive bacteria were detected in 10 (26.3%) patient samples and included Enterococcus faecalis (6 cases), Enterococcus faecium (3 cases), and Staphylococcus aureus (1 case) as the predominant species. No fungal species were detected, as shown in Table 3.

| Isolated microbes | Total strains | Frequency |

| Gram-negative | 28 | 73.7% |

| Escherichia coli | 19 | 50.0% |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 5 | 13.2% |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 2 | 5.3% |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | 2.6% |

| Enterobacter mirabilis | 1 | 2.6% |

| Gram-positive | 10 | 26.3% |

| Enterococcus faecalis | 6 | 15.8% |

| Enterococcus faecium | 3 | 7.9% |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 1 | 2.6% |

| Fungus | 0 | 0 |

Based on the antibiotics susceptibility test results, the pathogens were divided into sensitive, intermediate resistant, and resistant groups, and pathogens assigned to the latter two groups were included in the resistance rate analysis. Due to differences in test strips, the results of the susceptibility tests differed across the patients. The resistance rate of E. coli against cephalosporins decreased with more advanced generations, and the rates were 68.4%, 57.9%, 52.6%, and 47.3% for cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, and cefepime, respectively. The resistance rate against ciprofloxacin was similar to that against cefoxitin (42.1%). E. coli also displayed a high level of resistance against broad-spectrum penicillins, that is, 78.9% and 63.2% against ticarcillin and piperacillin, respectively. Furthermore, E. coli exhibited a resistance rate of 83.3% against amoxicillin in 12 of the specimens tested. The combination of piperacillin and the β-lactamase inhibitor tazobactam was effective against E. coli, as it was associated with a low resistance rate of 15.8%. In addition, almost all the isolated bacteria were sensitive to carbapenems, with the exception of one that was resistant to imipenem. K. pneumoniae showed a similar resistance spectrum to E. coli, except that it had lower resistance against amikacin and ciprofloxacin. Enterococcus spp. exhibited a high resistance rate of 88.9% against aminoglycosides (gentamicin and streptomycin), while E. faecalis exhibited 100% sensitivity to glycopeptide. In contrast, several strains of E. faecium were resistant to glycopeptides (1/3) and penicillins (2/3). The results are summarized in Tables 4 and 5. Finally, 24 of the 38 patients harbored MDR strains, with 10 (52.6%) E. coli strains and 1 (20%) K. pneumoniae strain producing extended spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs).

| Enterococcus faecalis (6) | Enterococcus faecium (3) | |||

| Antimicrobial agents | AST | Resistance (%) | AST | Resistance (%) |

| Gentamicin | 1S + 5I | 5 (83.3) | 3I | 3 (100) |

| Streptomycin | 1S + 4I + 1R | 5 (83.3) | 2I + 1R | 3 (100) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 3S + 3I | 3 (50) | 2S + 1R | 1 (33.3) |

| Levofloxacin | 5S + 1I | 1 (16.7) | 2S + 1R | 1 (33.3) |

| Vancomycin | 6S | 0 | 2S + 1I | 1 (33.3) |

| Teicoplanin | 6S | 0 | 3S | 0 |

| Ampicillin | 6S | 0 | 1S + 1I + 1R | 2 (66.7) |

| Penicillin | 6S | 0 | 1S + 2R | 2 (66.7) |

| Quinupristin-dalfopristin | 1S + 5R | 5 (83.3) | 2S + 1I | 1 (33.3) |

| Tetracycline | 3S + 3R | 3 (50) | 2S + 1R | 1 (33.3) |

| Rifampin | 1S + 1I + 4R | 5 (83.3) | 2S + 1R | 1 (33.3) |

| Erythromycin | 4I + 2R | 6 (100) | 1S + 2R | 2 (66.7) |

| Antimicrobial agents | Escherichia coli (n = 19) | Klebsiella pneumoniae (5) | Enterobacter cloacae (2) | Enterobacter aerogenes (1) | Enterobacter mirabilis (1) | ||

| AST | Resistance (%) | AST | Resistance (%) | AST | AST | AST | |

| Amikacin | 16S + 3R | 3 (15.8) | 5S | 0 | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Gentamicin | 12S + 7R | 7 (36.8) | 4S + 1R | 1 (20) | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Amoxicillin | 2S + 10R | - | 5R | 5 (100) | 1R | 1R | - |

| Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | 11S + 3I + 5R | 8 (42.1) | 3S + 1I + 1R | 2 (40) | 1R | 1I | 1S |

| Ticarcillin | 4S + 15R | 15 (78.9) | 5R | 5 (100) | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Ticarcillin/clavulanic acid | 4S + 8R | - | 3S + 1R | - | 1S + 1R | 1S | 1S |

| Piperacillin | 7S + 12R | 12 (63.2) | 1S + 3I + 1R | 4 (80) | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 16S + 3R | 3 (15.8) | 5S | 0 | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Cefazolin-1st | 1S + 5R | - | 1R | - | - | - | 1R |

| Cefoxitin | 11S + 8R | 8 (42.1) | 3S + 2R | 2 (40) | 1R | 1R | 1R |

| Cefuroxime-2nd | 6S + 13R | 13 (68.4) | 2S + 3R | 3 (60) | 2S | 1R | 1S |

| Cefotaxime-3rd | 8S + 1I + 10R | 11 (57.9) | 4S + 1I | 1 (25) | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| Ceftazidime-3rd | 9S + 10R | 10 (52.6) | 4S + 1R | 1 (25) | 2S | 1S | 1R |

| Cefepime-4th | 10S + 1I + 8R | 9 (47.3) | 4S + 1R | 1 (25) | 2S | 1S | 1S |

| ESBLs ( + ) | 10 | 10 (52.6) | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Ciprofloxacin | 11S + 8R | 8 (42.1) | 4S + 1R | 1 (20) | 2S | 1R | 1I |

| Imipenem | 18S + 1R | 1 (5.3) | 5S | 0 | 2S | 1S | 1R |

| Meropenem | 19S | 0 | 5S | 0 | 2S | 1S | 1S |

The gallbladder is a sterile organ, but pathological conditions, such as gallstones, polyps, and tumors, create favorable conditions for bacterial colonization by blocking bile circulation, which results in cholestasis[5,13]. Bacterial colonization can lead to inflammation of the biliary tract and even sepsis in severe cases. The main sources of biliary tract infection are the blood and duodenum[10]. In our study, bacteria were detected in the bile specimens of 20.5% cholelithiasis patients, and Enterobacteriaceae (73.7%; mainly E. coli and K. pneumoniae) and Enterococcus spp. (23.7%; E. faecium and E. faecalis) were the dominant species. Consistent with previous studies, most of the bacteria detected here were endogenous and of intestinal origin[12,14,15]. Unlike other studies, however, we did not detect Pseudomonas aeruginosa or any fungal species[15,16]; this could probably be explained by our limited sample size.

The risk of bacterial invasion of the bile is associated with biliary obstruction, older age (> 70 years), acute cholecystitis, CBDSs, cholangitis, ERCP before cholecystectomy, and dysfunctional gallbladder[8,15,17]. In our study, the presence of CBDSs and longer operation time were identified as independent risk factors for positive bile culture. In the case of positive bile culture, postoperative antibiotic use needs to be adjusted in order to minimize the risk of infection after surgery. Studies have shown a higher incidence of postoperative septic complications in patients with positive bile culture than in those without bile infection[6,8,18], with the overall rates varying from 0.9% to 20.0%[6,8,19]. In contrast to these studies, in the present study, the rate of septic complications was 3.2% in the negative culture group and 2.2% in the positive culture group. This indicates that there was no significant correlation between the presence of bacteria and biliary sepsis. The differences in the findings may be associated with the empirical use of cefotaxime/sulbactam sodium and the smaller sample size in our cohort.

According to the definition of MDR proposed by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control Advisory Forum in 2010, it is described as resistance to one agent of at least three or more classes of antibiotics, but it does not cover intrinsic resistance or resistance against a key antimicrobial agent[9]. In the present study, although the antibiotic sensitivity tests did not include all the relevant antibiotics, the lowest incidence of MDR was 63.2%, which indicates that the rate of MDR is high in pathogens that infect bile. Cephalosporins and quinolones are commonly used to treat biliary tract infections, and the concentration of these drugs increases in bile after their absorption and metabolism[20,21]. However, as a result of the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria, the efficacy of conventional antibacterial drugs has begun to decline[9,10]. In this study, the gram-negative bacteria showed nearly 100% sensitivity to meropenem and imipenem, while 40% of the strains were resistant to cephalosporins and quinolones and over 50% were resistant to second- or third-generation cephalosporins. This high rate of resistance is mainly attributed to the emergence of ESBL-producing bacteria, which accounted for 52.6% of the E. coli strains isolated from our cohort. Therefore, the empirical treatment of biliary infections should take into account ESBL-producing bacteria. Treatment with multiple drug combinations, including β-lactamase inhibitors, has been highly effective against gram-negative bacilli[21-23]. This was confirmed by the high sensitivity of E. coli to piperacillin and tazobactam in the present study; however, E. coli exhibits a fairly high resistance rate against ticarcillin/clavulanic acid or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. Aminoglycosides are also used to treat biliary infections[20], and the resistance rates of E. coli against gentamicin and amikacin were found to be 36.8% and 15.8%, respectively.

MDR Enterococcus spp. has been increasingly detected in recent years, and these species exhibit intrinsic resistance to most cephalosporins and carbapenems[9,24]. The overall prevalence of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus, one of the major nosocomial pathogens worldwide[25], is 5%-20%[25,26]. In this study, Enterococcus spp., especially E. faecalis, were highly sensitive to ampicillin and penicillin. Interestingly, while only 14.7% of E. faecalis strains isolated in Japan are resistant to β-lactam antibiotics, 85.7% of the E. faecium strains are resistant to ampicillin and all strains of both species are resistant to penicillin[26]. In addition, Enterococcus spp. were found to be highly resistant to aminoglycosides and sensitive to teicoplanin, and only one vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus strain was detected in our study. All these results indicate that the antibiotic regimen against biliary infections should be based on both the antibacterial spectrum of the drugs and the resistance patterns. Therefore, clinicians should routinely test bile samples collected during cholecystectomy in order to monitor the pathogenic species and drug susceptibility. This will not only provide a definite guide for postoperative treatment, but also provide data for future empirical use of antimicrobial agents.

This single-center retrospective study is based on data from hospital medical records, and several limitations should be noted. This study is limited by its retrospective design, that is, a heterogeneous population and the possibility of a type II error. In particular, owing to the small number of patients included, further studies are required to validate our findings.

The risk of biliary infection increases in patients with cholelithiasis, and the risk is higher in patients with CBDSs and longer operation time. The dominant pathogens detected in this study were E. coli, K. pneumoniae, E. faecium, and E. faecalis. In addition, the combination of β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors was found to be an effective first-line treatment against bile pathogens. However, we must also be aware of the emergence of resistance to certain types of drugs.

Bacterial infection is an important cause of cholelithiasis or gallstones and interferes with its treatment.

Identified microbial spectrum and drug resistance of pathogens cultured from gallbladder bile specimens is helpful for targeted preventive and therapeutic drugs in the perioperative period.

Investigate the bile microbial spectrum of patients with cholelithiasis and the drug susceptibility patterns in order to establish an empirical antibiotic treatment for cholelithiasis-associated infection.

A retrospective single-center study was conducted on patients diagnosed with cholelithiasis between May 2013 and December 2018.

The presence of common bile duct stones (OR = 5.4, 95%CI: 1.3-21.9, P = 0.03) and longer operation time (> 80 min) (OR = 4.3, 95%CI: 1.4-13.1, P = 0.01) were identified as independent risk factors for positive bile culture. Gram-negative bacteria were detected in 28 positive bile specimens, and Escherichia coli (E. coli) (19/28) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (5/28) were the most frequently identified species. Gram-positive bacteria were present in 10 specimens. All the isolated E. coli strains were sensitive to carbapenems, with the exception of one imipenem-resistant strain. K. pneumoniae showed a similar resistance spectrum to E. coli. Enterococcus spp. was largely sensitive to glycopeptides and penicillin, except for a few strains of E. faecium.

The presence of common bile duct stones and longer operation time were identified as independent risk factors for positive bile culture in patients with cholelithiasis. The most commonly detected bacterium was E. coli. The combination of β-lactam antibiotics and β-lactamase inhibitors prescribed perioperatively appears to be effective against bile pathogens and is recommended.

To explore the characteristics of patients infected with drug-resistant bacteria and the prevention and treatment of drug-resistant bacteria.

| 1. | Pokharel N, Rodrigues G, Shenoy G. Evaluation of septic complications in patients undergoing biliary surgery for gall stones in a tertiary care teaching hospital of South India. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2007;5:371-373. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Abeysuriya V, Deen KI, Wijesuriya T, Salgado SS. Microbiology of gallbladder bile in uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:633-637. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Mir MA, Malik UY, Wani H, Bali BS. Prevalence, pattern, sensitivity and resistance to antibiotics of different bacteria isolated from port site infection in low risk patients after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic cholelithiasis at tertiary care hospital of Kashmir. Int Wound J. 2013;10:110-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Karpel E, Madej A, Bułdak Ł, Duława-Bułdak A, Nowakowska-Duława E, Łabuzek K, Haberka M, Stojko R, Okopień B. Bile bacterial flora and its in vitro resistance pattern in patients with acute cholangitis resulting from choledocholithiasis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:925-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Salvador VB, Lozada MC, Consunji RJ. Microbiology and antibiotic susceptibility of organisms in bile cultures from patients with and without cholangitis at an Asian academic medical center. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2011;12:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Galili O, Eldar S Jr, Matter I, Madi H, Brodsky A, Galis I, Eldar S Sr. The effect of bactibilia on the course and outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:797-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Velázquez-Mendoza JD, Alvarez-Mora M, Velázquez-Morales CA, Anaya-Prado R. Bactibilia and surgical site infection after open cholecystectomy. Cir Cir. 2010;78:239-243. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Morris-Stiff GJ, O'Donohue P, Ogunbiyi S, Sheridan WG. Microbiological assessment of bile during cholecystectomy: is all bile infected? HPB (Oxford). 2007;9:225-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:268-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6072] [Cited by in RCA: 9407] [Article Influence: 627.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Maseda E, Maggi G, Gomez-Gil R, Ruiz G, Madero R, Garcia-Perea A, Aguilar L, Gilsanz F, Rodriguez-Baño J. Prevalence of and risk factors for biliary carriage of bacteria showing worrisome and unexpected resistance traits. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:518-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kanafani ZA, Khalifé N, Kanj SS, Araj GF, Khalifeh M, Sharara AI. Antibiotic use in acute cholecystitis: practice patterns in the absence of evidence-based guidelines. J Infect. 2005;51:128-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Suna N, Yıldız H, Yüksel M, Parlak E, Dişibeyaz S, Odemiş B, Aydınlı O, Bilge Z, Torun S, Tezer Tekçe AY, Taşkıran I, Saşmaz N. The change in microorganisms reproducing in bile and blood culture and antibiotic susceptibility over the years. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2014;25:284-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kaya M, Beştaş R, Bacalan F, Bacaksız F, Arslan EG, Kaplan MA. Microbial profile and antibiotic sensitivity pattern in bile cultures from endoscopic retrograde cholangiography patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3585-3589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhao J, Wang Q, Zhang J. Changes in Microbial Profiles and Antibiotic Resistance Patterns in Patients with Biliary Tract Infection over a Six-Year Period. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2019;20:480-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Yun SP, Seo HI. Clinical aspects of bile culture in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Darkahi B, Sandblom G, Liljeholm H, Videhult P, Melhus Å, Rasmussen IC. Biliary microflora in patients undergoing cholecystectomy. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15:262-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Landau O, Kott I, Deutsch AA, Stelman E, Reiss R. Multifactorial analysis of septic bile and septic complications in biliary surgery. World J Surg. 1992;16:962-4; discussion 964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nomura T, Shirai Y, Hatakeyama K. Impact of bactibilia on the development of postoperative abdominal septic complications in patients with malignant biliary obstruction. Int Surg. 1999;84:204-208. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Spaziani E, Picchio M, Di Filippo A, Greco E, Cerioli A, Maragoni M, Faccì G, Lucarelli P, Marino G, Stagnitti F, Narilli P. Antibiotic prophylaxis in elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy is useless. A prospective multicenter study. Ann Ital Chir. 2015;86:228-233. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Westphal JF, Brogard JM. Biliary tract infections: a guide to drug treatment. Drugs. 1999;57:81-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bassotti G, Chistolini F, Sietchiping-Nzepa F, De-Roberto G, Morelli A. Empirical antibiotic treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam in patients with microbiologically-documented biliary tract infections. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2281-2283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dervisoglou A, Tsiodras S, Kanellakopoulou K, Pinis S, Galanakis N, Pierakakis S, Giannakakis P, Liveranou S, Ntasiou P, Karampali E, Iordanou C, Giamarellou H. The value of chemoprophylaxis against Enterococcus species in elective cholecystectomy: a randomized study of cefuroxime vs ampicillin-sulbactam. Arch Surg. 2006;141:1162-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rodríguez-Baño J, Navarro MD, Romero L, Muniain MA, de Cueto M, Ríos MJ, Hernández JR, Pascual A. Bacteremia due to extended-spectrum beta -lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the CTX-M era: a new clinical challenge. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1407-1414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Treitman AN, Yarnold PR, Warren J, Noskin GA. Emerging incidence of Enterococcus faecium among hospital isolates (1993 to 2002). J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:462-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Amberpet R, Sistla S, Parija SC, Rameshkumar R. Risk factors for intestinal colonization with vancomycin resistant enterococci' A prospective study in a level III pediatric intensive care unit. J Lab Physicians. 2018;10:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Abamecha A, Wondafrash B, Abdissa A. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Enterococcus species isolated from intestinal tracts of hospitalized patients in Jimma, Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Janvilisri T, Thailand; Sahle Z, Ethiopia S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Chen YL