Published online Jan 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i1.46

Peer-review started: March 25, 2021

First decision: June 16, 2021

Revised: June 29, 2021

Accepted: December 22, 2021

Article in press: December 22, 2021

Published online: January 27, 2022

Processing time: 299 Days and 14.8 Hours

Despite improvements in surgical procedures and peri-operative patients management, the postoperative complications in esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer remain high because of technical aspects. Several studies have indicated the negative influence of postoperative infectious complications on long-term survival after gastrointestinal surgery. However, no study has shown the association between postoperative complications and long-term survival of patients with EGJ cancer.

To elucidate influence of postoperative complications on the long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

A total of 122 patients who underwent surgery for EGJ cancer at the Keio University were included in this study. We examined the association between complications and long-term oncologic outcomes.

In all patients, the 3-year overall survival (OS) rate was 71.9%, and the recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate was 67.5%. Compared with patients without anastomotic leakage, those with anastomotic leakage had poor median OS (8 mo vs not reached, P = 0.028) and median RFS (5 mo vs not reached, P = 0.055). Among patients with cervical anastomosis, there were not significant differences between patients with and without anastomotic leakage. However, among patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis, patients with anastomotic leakage had significantly worse OS (P = 0.002) and RFS (P = 0.005).

Anastomotic leakage was significantly associated with long-term oncologic outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer, especially those who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis. Cervical anastomosis with subtotal esophagectomy may be an option for the patients who are at high risk for anastomotic leakage.

Core Tip: The postoperative complications of gastrointestinal surgery had been reported to have a remarkable effect on the long-term outcomes, but no study had examined this association in esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer. This retrospective study found that anastomotic leakage was remarkably associated with the survival of patients with EGJ cancer who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis but not cervical anastomosis. Cervical anastomosis with subtotal esophagectomy may be an option for patients who have a high risk for anastomotic leakage.

- Citation: Takeuchi M, Kawakubo H, Matsuda S, Mayanagi S, Irino T, Okui J, Fukuda K, Nakamura R, Wada N, Takeuchi H, Kitagawa Y. Association of anastomotic leakage with long-term oncologic outcomes of patients with esophagogastric junction cancer. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(1): 46-55

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i1/46.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i1.46

Esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer has been increasing not only in the United States and Western countries but also in Japan[1-5]. However, the optimal surgical approach for EGJ cancer remains controversial[6]. Despite improvements in surgical procedures and peri-operative patients management, the complications after surgery for EGJ cancer remain high because of technical aspects[7]. EGJ has complex anatomical features with several adjacent organs, such as the spleen, diaphragm, and some thoracic organs[8]. Therefore, obtaining a negative surgical margin is often difficult because of the restricted space. In some cases, intrathoracic anastomosis is needed to achieve a clear margin, both macroscopically and microscopically[5]. A multicenter prospective study showed the occurrence of postoperative complications of any grade in around 40% of patients; in particular, postoperative anastomotic leakage developed in 11.9% after a transhiatal approach and in 13.2% after a transthoracic approach[9].

Postoperative infectious complications have been reported to have an adverse influence on the long-term outcomes after esophagectomy [10-12]. The negative influence of these complications may be attributed to cytokines changes which are associated with residual cancer cell progression[13,14]. However, to date, no study has shown the influence of postoperative complications on the long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

We hypothesized the association of postoperative complications, including anastomotic leakage, which is the most common, with the long-term oncologic outcomes after surgery for EGJ cancer. The aim of this study is to elucidate the influence of postoperative complications on the long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

This study included 122 patients who had undergone surgery for EGJ cancer at the Keio University between 2003 and 2017. We defined EGJ cancer according to Nishi's classification[15]. The location of the EGJ was defined at the level of macroscopic change in the caliber of the resected esophagus and stomach. A tumor that had an epicenter in the area of the EGJ and extended from 2 cm above to 2 cm below the EGJ was diagnosed as EGJ cancer. We included patients who were diagnosed as cM1 if there was involvement of the supraclavicular lymph node[16].

Using hospital records, the patients’ clinical characteristics, surgical procedure, and outcomes were evaluated retrospectively. The OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS) were calculated from the start date of surgery. The clinical and pathologic stages of the cancer were based on the seventh edition of the Union Against Cancer for esophageal cancer[17]. The tumor status was determined by the residual tumor classification: R0, no residual tumor or R1, microscopic residual tumor[18]. This study had approval from the ethics committee of Keio University School of Medicine.

At our institution, the decision making for the surgical procedures for EGJ cancer included the performance of subtotal esophagectomy for: (1) advanced cancer deeper than T2, with the tumor epicenter on the esophageal side; (2) advanced cancer deeper than T2, with the tumor epicenter on the gastric side and with > 30 mm of esophageal invasion; or (3) cancer with clinically positive upper and/or middle mediastinal lymph node. The remaining patients mainly underwent transhiatal approach for lower esophageal resection; however, transthoracic approach was selected if performing transhiatal anastomosis or obtaining a negative proximal margin was expected to be difficult.

The thoracic approach was performed through a right thoracic incision or by video-assisted thoracic surgery in a hybrid position that combined the left decubitus and prone positions. Posterior mediastinal routes were mainly used for esophageal reconstructions with gastric conduits or colons. Moreover, we usually performed intrathoracic anastomosis in the cervical site by hand sewing but have elected to use a circular stapler in some cases. Transhiatal procedures are approached from the abdominal side. In this approach, we performed a total or proximal gastrectomy with resection of the distal esophagus. We used the jejunum for the double-tract or Roux-en-Y reconstruction or performed an esophagogastrostomy. Esophagogastrostomy was done mainly using the double-flap method with hand-sewn anastomosis. Double-tract or Roux-en-Y were performed using a circular stapler, hand -sewn or linear stapler.

We routinely performed esophagogastric roentgenography and computed tomography for 7 d after surgery to assess the presence of any complications, including anastomotic leakage. The Clavien–Dindo classification was used to assess postoperative complications[19]: Grade 3 was defined as complications requiring surgical, endoscopic, or radiologic intervention. Grade 4 was defined as a life-threatening complication requiring intensive care unit management. Anastomotic leakage was diagnosed based on computed tomography scan or esophagography findings and/or the characteristics of the anastomotic drains. Pneumonia was diagnosed on the basis of the postoperative body temperature, leukocyte count, and pulmonary radiograph findings[3].

We used Stata/SE 12.1 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States) for statistical analyses. For the univariate analysis, categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-square test and continuous variables were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. We entered significant variables with P values < 0.10 into a logistic regression model for multivariate analysis. Moreover, we examined prognosis using the Kaplan-Meier method and log-rank test; we entered significant variables with P values < 0.10 into a Cox hazard regression model for multivariate analysis.

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the study patients are shown in Table 1. Of the 122 patients (96 men and 26 women), 95 patients (77.9%) had adenocarcinoma and 27 patients (22.1%) had squamous cell carcinoma. Transhiatal approach was performed on 75 patients (61.5%); transthoracic approach was performed on 47 patients (38.5%). Subtotal esophagectomy was performed on 41 patients (33.6%), and total gastrectomy was performed on 37 patients (30.3%).

| All (n = 122) | |

| Sex | |

| Male/female | 96 (78.7%)/26 (21.3%) |

| Age, median (min, max) | 68 (35-87) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma/squamous cell carcinoma | 95 (77.9%)/27 (22.1%) |

| Neoadjuvant | 32 (26.2%) |

| Adjuvant | 27 (22.1%) |

| Approach | |

| Transthoracic/transhiatal | 47 (38.5%)/75 (61.5%) |

| Reconstruction site | |

| Cervical/Intrathoracic | 22 (18.0%)/100 (82.0%) |

| Subtotal esophagectomy | 41 (33.6%) |

| Total gastrectomy | 37 (30.3%) |

| Splenectomy | 16 (13.1%) |

| Operating time (min); median (range) | 299 (114-775) |

| Amount of bleeding (mL); median (range) | 180 (10-4858) |

| Tumor epicenter | |

| Esophageal side/gastric side | 52 (42.6%)/70 (57.4%) |

| Distance from the EGJ to the tumor center (mm) | 1.5 (-201-20) |

| Esophageal invasion (mm) | 11.5 (0-55) |

| Tumor diameter (mm) | 32 (6-100) |

| Pathologic stage of esophageal cancer | |

| Stage I/stage II/stage III/stage IV | 44 (36.1%)/24 (19.7%)/38 (31.2%)/16 (13.1%) |

| Residual cancer | |

| R0/R1 | 111 (91.0%)/11 (9.0%) |

The most commonly observed complication after surgery was pneumonia in 12 patients (9.8%), followed by anastomotic leakage in eight patients (6.6%) and recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis in six patients (5%). However, the most common grade 2 or higher complication was anastomotic leakage. Hospital death occurred in one patient (0.8%) (Table 2).

| All grades | Grade 3/4 | |

| Overall complications | 40 (32.8%) | 17 (13.9%) |

| Pneumonia | 12 (9.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 8 (6.6%) | 7 (5.7%) |

| Recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis | 6 (5%) | 0 |

| Wound infection | 4 (3.3%) | 0 |

| Chyle leakage | 3 (2.5%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Hemorrhage | 2 (1.7%) | 2 (1.7%) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 3 (2.5%) | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2 (1.7%) | 0 |

| Abdominal abscess | 3 (2.5%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Gastric tube-bronchial fistula | 1 (0.8%) | 1 (0.8%) |

| Others | 9 (7.4%) | 3 (2.5%) |

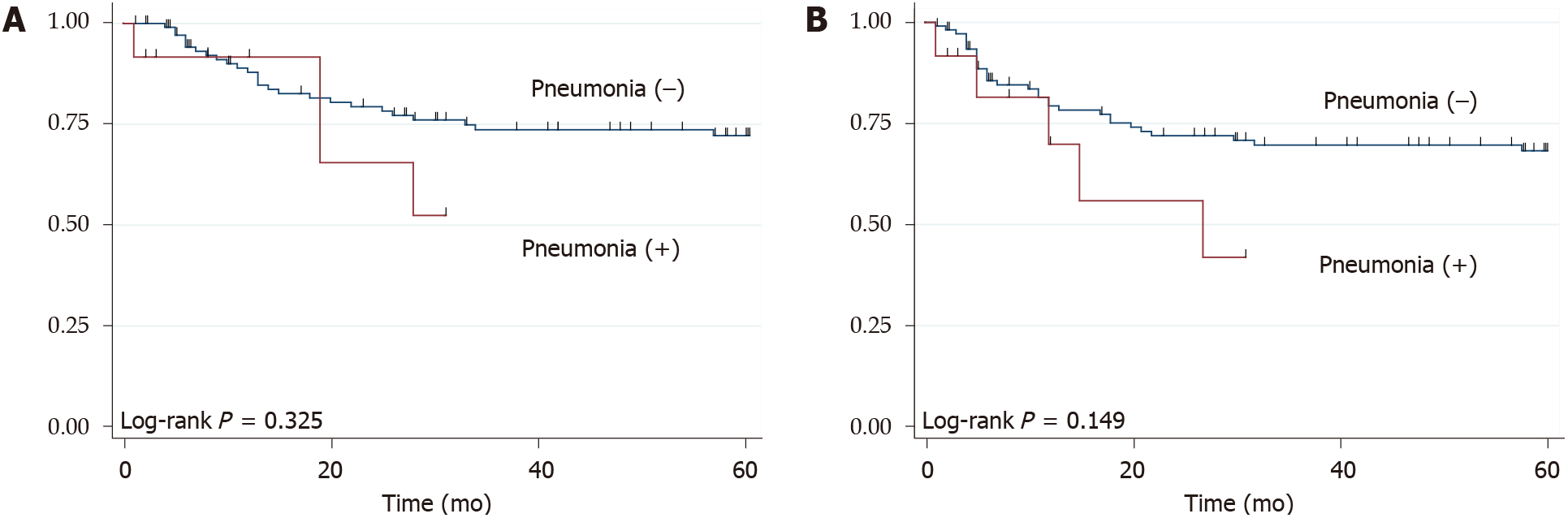

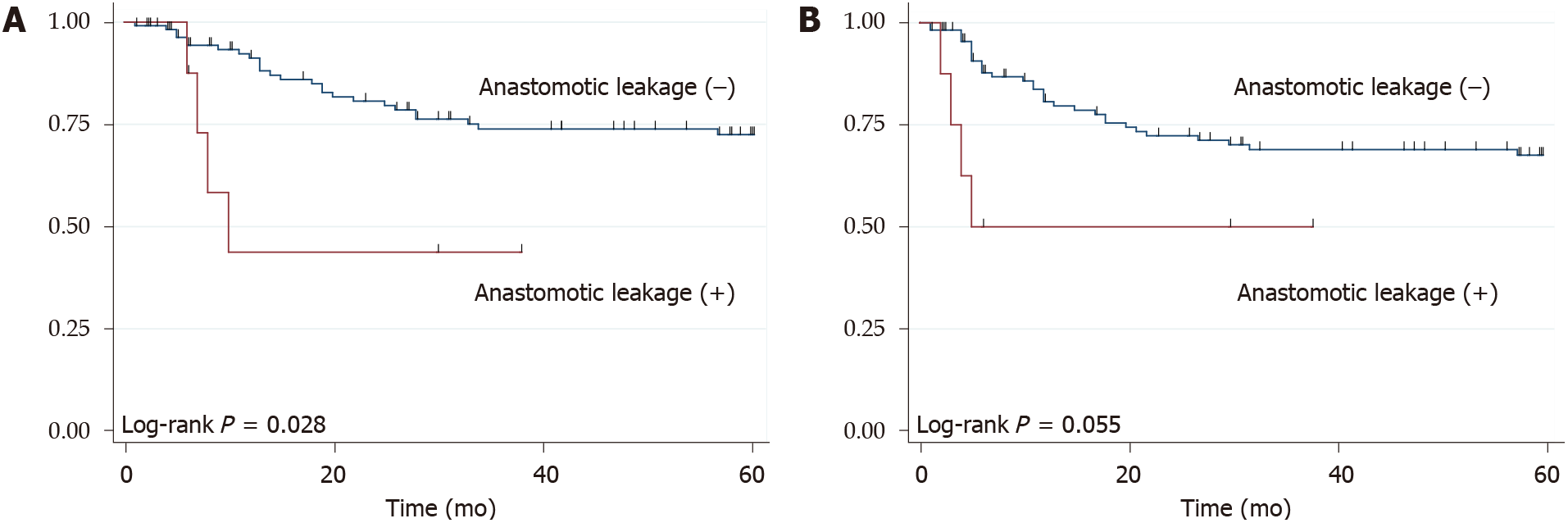

The 3 year OS rate and RFS rate was 71.9% and 67.5%, respectively. During the term of the surveillance, 35 patients (28.7%) developed recurrence and 34 patients (27.9%) died. There weren’t significant differences between patients with and without pneumonia, both in the OS (P = 0.325) and RFS (P = 0.149) (Figure 1). However, compared with patients without anastomotic leakage, those with anastomotic leakage had poor median OS (8 mo vs not reached, P = 0.028) and median RFS (5 mo vs not reached, P = 0.055) (Figure 2).

According to the univariate analyses, age, histology, neoadjuvant therapy, pStage, R1, and anastomotic leakage were the risk factors for death. On multivariate analyses, age, pStage III/IV, and anastomotic leakage were identified as the significant risk factors for death (Table 3). Moreover, anastomotic leakage was a significant risk factor for RFS (Supplementary Table 1).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Male (vs female) | 0.71 (0.34–1.49) | 0.365 | ||

| Age (per 1 year increase) | 1.06 (1.02-1.09) | 0.004 | 1.05 (1.01-1.08) | 0.014 |

| SCC (vs AC) | 2.06 (1.02-4.16) | 0.045 | 1.20 (0.50-2.87) | 0.674 |

| Neoadjuvant + (vs neoadjuvant-) | 2.22 (1.11-4.44) | 0.025 | 1.61 (0.72-3.58) | 0.244 |

| Adjuvant + (vs adjuvant-) | 1.76 (0.86-3.62) | 0.122 | ||

| Transthoracic approach (vs transhiatal approach) | 1.64 (0.83-3.22) | 0.148 | ||

| pStage III/IV (vs pStage I/II) | 9.55 (3.68-24.76) | < 0.001 | 7.14 (2.67-19.13) | < 0.001 |

| R1 (vs R0) | 2.62 (1.08-6.35) | 0.033 | 1.79 (0.69-4.68) | 0.232 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3.07 (1.07-8.80) | 0.037 | 3.59 (1.11-11.58) | 0.032 |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 1.68 (0.59-4.78) | 0.332 | ||

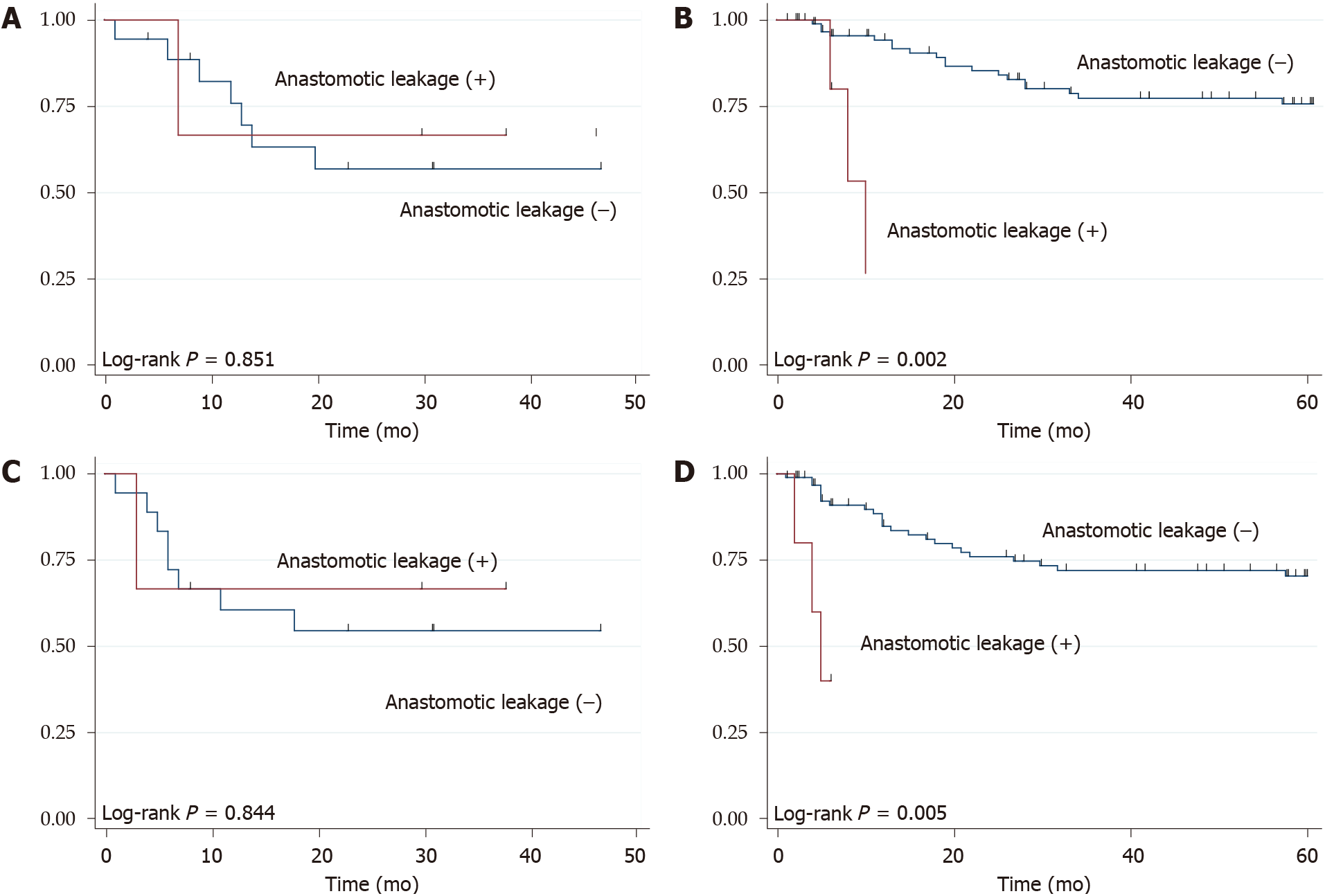

Among patients with cervical anastomosis, there weren’t significant differences between patients with and without anastomotic leakage. However, among patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis, patients with anastomotic leakage, compared with those without anastomotic leakage, had significantly worse OS (P = 0.002) and RFS (P = 0.005) (Figure 3).

Lymph node metastases were the most common pattern of recurrence (23 patients), followed by hematogenous (19 patients), peritoneal (seven patients), and local (four patients). These three patterns of recurrence were significantly observed in patients with anastomotic leakage (Table 4).

| All (n = 122) | Anastomotic leakage | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 8) | No (n = 114) | |||

| Hematogenous | 19 (15.6%) | 4 (50%) | 15 (13.2%) | 0.005 |

| Lymphatic | 23 (18.9%) | 3 (37.5%) | 20 (17.5%) | 0.163 |

| Peritoneal | 7 (5.7%) | 2 (25%) | 5 (4.4%) | 0.015 |

| Local | 4 (3.3%) | 2 (25%) | 2 (1.8%) | < 0.001 |

We examined the risk factors for anastomotic leakage using the clinicopathologic characteristics and the surgical procedural factors. On univariate analyses, amount of bleeding, operating time, and tumor diameter were the risk factors for anastomotic leakage. Notably, surgical procedural factors were not identified as predictors of anastomotic leakage. On multivariate analysis that included these factors, only tumor diameter was identified as a predictor of anastomotic leakage (HR: 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01–1.08, P = 0.020) (Supplementary Table 2). On subanalysis, tumor diameter was a significant risk factor for anastomotic leakage in patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis (P = 0.009) but not in those who underwent cervical anastomosis (P = 0.886).

The present retrospective study demonstrated that anastomotic leakage was significantly associated with the long-term oncologic outcomes, including OS and RFS, in patients with EGJ cancer. Notably, these tendencies were observed not in patients who underwent cervical anastomosis but in those who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis. Although several studies have indicated the relationship between survival and postoperative complications, this was the first report that demonstrated the negative influence of postoperative complications on the oncological outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

Some studies have reported that postoperative anastomotic leakage had a negative influence on the long-term outcomes of upper gastrointestinal surgery. Markar et al[20] reported that anastomotic leakage after esophagectomy was associated with poor OS and disease-specific survival rates and with an increase in cancer recurrence rates. Likewise, Andreou et al[21] showed that anastomotic leakage had a negative influence on the long-term survival after gastric and esophageal resection. In our study, the recurrence rate was also significant higher in patients with anastomotic leakage than in those without anastomotic leakage. As previously indicated, cytokine changes due to postoperative complications may be relevant to tumor proliferation, survival, and progression to metastasis[13]. Therefore, inflammatory response secondary to anastomotic leakage was suggested to promote tumor regrowth and lead to poor long-term outcomes. In particular, patients with leakage of the intrathoracic anastomosis after surgery may have suffered more severe systemic inflammation, compared with the patients who had leakage of the cervical anastomosis, because inflammation can spread inside the thoracic cavity and easily develop to mediastinitis. Therefore, these trends were more prevalent in patients with intrathoracic anastomosis than in those with cervical anastomosis. On the other hand, in cases of cervical anastomosis leakage, inflammation can often be localized.

Our previous study indicated that postoperative pneumonia, not anastomotic leakage, was associated with the long-term outcomes after esophagectomy[10]; however, patients with EGJ cancer had the opposite tendency. This is due to the difference in the surgical approach between esophageal cancer and EGJ cancer. As we described above, patients with leakage of intrathoracic anastomosis may have suffered relatively worse systemic inflammation; this may explain the association of anastomotic leakage with the long-term outcomes after surgery for EGJ cancer in those with intrathoracic anastomosis but not in those with cervical anastomosis. Conversely, pneumonia was not associated with the long-term outcomes after surgery for EGJ cancer, probably because of the manipulation and effects on the lungs during surgery. On the other hand, the procedure of esophagectomy for esophageal cancer is mainly performed in the thoracic cavity, therefore, pneumonia after esophagectomy should be considered as a possible poor prognostic factor with a large impact on pulmonary function.

In this study, tumor diameter was a significant risk factor for anastomotic leakage, especially in patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis. This result suggested that performing anastomosis for a large tumor invading the esophageal side may cause anastomotic leakage because of technical difficulties. Therefore, cervical anastomosis with subtotal esophagectomy should be chosen for patients who have a high risk for anastomotic leakage, including those with large tumor diameter. Conversely, pStage is not a significant risk factor. Moreover, anastomotic leakage was a significant predictor for oncological outcomes, independent of tumor, node and metastasis stage, according to the multivariate analyses. Therefore, we concluded that anastomotic leakage also is associated with survival, in addition to pStage.

We have used Nishi’s classification in this study; however, the Siewert classification has been adopted mainly in Western countries as the histological type is predominantly adenocarcinoma. Although an EGJ tumor defined by Nishi’s classification and Siewert type 2 is almost similar, the tumor epicenter with Nishi’s classification is 1 cm higher than is that of Siewert type 2. Therefore, performing intrathoracic anastomosis may be difficult in EGJ cancer defined with Nishi’s classification vs Siewert type 2 cancer, and the relationship between survival and anastomotic leakage may be weak if only patients with Siewert type 2 cancers were enrolled in the study.

This study had several limitations. First, the retrospective single-center study design that was limited to a Japanese population was an element of selection bias. Second, we did not consider the association between the complication’s grades and long-term outcome in this study. In particular, we did not examine the difference in anastomotic leakage severity between cervical anastomosis and intrathoracic anastomosis.

Anastomotic leakage was significantly associated with the long-term oncologic outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer in patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis but not in those who underwent cervical anastomosis. Cervical anastomosis with subtotal esophagectomy may be an option for patients who have a high risk of anastomotic leakage.

Despite improvements in surgical procedures and peri-operative patients management, complications after surgery for esophagogastric junction (EGJ) cancer remain high because of technical difficulty.

No study has shown the influence of postoperative complications on the long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

To elucidate the influence of postoperative complications, such as anastomotic leakage and pneumonia, on the long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

We retrospectively analyzed 122 patients who underwent surgery for EGJ cancer, investigating the association between postoperative complications and oncological outcomes.

We identified anastomotic leakage as a significant risk factor for death and cancer recurrence. We did not observe this tendency in patients who underwent cervical anastomosis but did see this tendency in patients who underwent intrathoracic anastomosis.

Postoperative anastomotic leakage was significantly associated with survival in patients with EGJ cancer. Cervical anastomosis with esophagectomy may be an option for patients with a high risk of anastomotic leakage.

A prospective study is required to confirm the association between complications and long-term outcomes of patients with EGJ cancer.

The authors thank Kumiko Motooka, a staff member at the Department of Surgery in the Keio University School of Medicine, for her help in the preparation of this manuscript.

| 1. | Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ, Katai H, Kato H, Taniguchi H, Shimoda T. Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1662-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dikken JL, Lemmens VE, Wouters MW, Wijnhoven BP, Siersema PD, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, van Sandick JW, Cats A, Verheij M, Coebergh JW, van de Velde CJ. Increased incidence and survival for oesophageal cancer but not for gastric cardia cancer in the Netherlands. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1624-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dubecz A, Solymosi N, Stadlhuber RJ, Schweigert M, Stein HJ, Peters JH. Does the Incidence of Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagus and Gastric Cardia Continue to Rise in the Twenty-First Century? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vizcaino AP, Moreno V, Lambert R, Parkin DM. Time trends incidence of both major histologic types of esophageal carcinomas in selected countries, 1973-1995. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:860-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chevallay M, Bollschweiler E, Chandramohan SM, Schmidt T, Koch O, Demanzoni G, Mönig S, Allum W. Cancer of the gastroesophageal junction: a diagnosis, classification, and management review. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1434:132-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shiraishi O, Yasuda T, Kato H, Iwama M, Hiraki Y, Yasuda A, Shinkai M, Kimura Y, Imano M. Risk Factors and Prognostic Impact of Mediastinal Lymph Node Metastases in Patients with Esophagogastric Junction Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:4433-4440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ji L, Wang T, Tian L, Gao M. The early diagnostic value of C-reactive protein for anastomotic leakage post radical gastrectomy for esophagogastric junction carcinoma: A retrospective study of 97 patients. Int J Surg. 2016;27:182-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Delattre JF, Avisse C, Marcus C, Flament JB. Functional anatomy of the gastroesophageal junction. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:241-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kurokawa Y, Takeuchi H, Doki Y, Mine S, Terashima M, Yasuda T, Yoshida K, Daiko H, Sakuramoto S, Yoshikawa T, Kunisaki C, Seto Y, Tamura S, Shimokawa T, Sano T, Kitagawa Y. Mapping of Lymph Node Metastasis From Esophagogastric Junction Tumors: A Prospective Nationwide Multicenter Study. Ann Surg. 2021;274:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 36.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Booka E, Takeuchi H, Nishi T, Matsuda S, Kaburagi T, Fukuda K, Nakamura R, Takahashi T, Wada N, Kawakubo H, Omori T, Kitagawa Y. The Impact of Postoperative Complications on Survivals After Esophagectomy for Esophageal Cancer. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Baba Y, Yoshida N, Shigaki H, Iwatsuki M, Miyamoto Y, Sakamoto Y, Watanabe M, Baba H. Prognostic Impact of Postoperative Complications in 502 Patients With Surgically Resected Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Retrospective Single-institution Study. Ann Surg. 2016;264:305-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamashita K, Makino T, Miyata H, Miyazaki Y, Takahashi T, Kurokawa Y, Yamasaki M, Nakajima K, Takiguchi S, Mori M, Doki Y. Postoperative Infectious Complications are Associated with Adverse Oncologic Outcomes in Esophageal Cancer Patients Undergoing Preoperative Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2106-2114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto M, Shimokawa M, Yoshida D, Yamaguchi S, Ohta M, Egashira A, Ikebe M, Morita M, Toh Y. The survival impact of postoperative complications after curative resection in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: propensity score-matching analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020;146:1351-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tsujimoto H, Kobayashi M, Sugasawa H, Ono S, Kishi Y, Ueno H. Potential mechanisms of tumor progression associated with postoperative infectious complications. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021;40:285-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2952] [Article Influence: 196.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part II and III. Esophagus. 2017;14:37-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumours. 7th ed. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2009. |

| 18. | Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus. 2017;14:1-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 741] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 19. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 26181] [Article Influence: 1190.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 20. | Markar S, Gronnier C, Duhamel A, Mabrut JY, Bail JP, Carrere N, Lefevre JH, Brigand C, Vaillant JC, Adham M, Msika S, Demartines N, Nakadi IE, Meunier B, Collet D, Mariette C; FREGAT (French Eso-Gastric Tumors) working group, FRENCH (Fédération de Recherche EN CHirurgie), and AFC (Association Française de Chirurgie). The Impact of Severe Anastomotic Leak on Long-term Survival and Cancer Recurrence After Surgical Resection for Esophageal Malignancy. Ann Surg. 2015;262:972-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Andreou A, Biebl M, Dadras M, Struecker B, Sauer IM, Thuss-Patience PC, Chopra S, Fikatas P, Bahra M, Seehofer D, Pratschke J, Schmidt SC. Anastomotic leak predicts diminished long-term survival after resection for gastric and esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2016;160:191-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Herbella FAM S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H