Published online Sep 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i9.1063

Peer-review started: January 25, 2021

First decision: June 17, 2021

Revised: June 18, 2021

Accepted: July 22, 2021

Article in press: July 22, 2021

Published online: September 27, 2021

Processing time: 235 Days and 19.6 Hours

Rectocele is commonly seen in parous women and sometimes associated with symptoms of obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS).

To assess the current literature in regard to the outcome of the classical transperineal repair (TPR) of rectocele and its technical modifications.

An organized literature search for studies that assessed the outcome of TPR of rectocele was performed. PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar were queried in the period of January 1991 through December 2020. The main outcome measures were improvement in ODS symptoms, improvement in sexual functions and continence, changes in manometric parameters, and quality of life.

After screening of 306 studies, 24 articles were found eligible for inclusion to the review. Nine studies (301 patients) assessed the classical TPR of rectocele. The median rate of postoperative improvement in ODS symptoms was 72.7% (range, 45.8%-83.3%) and reduction in rectocele size ranged from 41.4%-95.0%. Modifications of the classical repair entailed omission of levatorplasty, addition of implant, concomitant lateral internal sphincterotomy, changing the direction of plication of rectovaginal septum, and site-specific repair.

The transperineal repair of rectocele is associated with satisfactory, yet variable, improvement in ODS symptoms with parallel increase in quality-of-life score. Several modifications of the classical TPR were described. These modifications include omission of levatorplasty, insertion of implants, performing lateral sphincterotomy, changing the direction of classical plication, and site-specific repair. The indications for these modifications are not yet fully clear and need further prospective studies to help tailor the technique to rectocele patients.

Core Tip: An organized literature search for studies that assessed the outcome of transperineal repair of rectocele was performed. Out of 306 studies, 24 were found eligible for inclusion to this review. Nine studies (301 patients) assessed the classical transperineal repair of rectocele. The median rate of postoperative improvement in obstructed defecation syndrome symptoms was 72.7% (range, 45.8%-83.3%), whereas reduction in rectocele size ranged from 41.4%-95.0%. Modifications of the classical repair entailed omission of levatorplasty, addition of implant, concomitant lateral internal sphincterotomy, changing the direction of plication of rectovaginal septum, and site-specific repair.

- Citation: Fathy M, Elfallal AH, Emile SH. Literature review of the outcome of and methods used to improve transperineal repair of rectocele. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(9): 1063-1078

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i9/1063.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i9.1063

Rectocele is a variant of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) that is defined as the herniation of the rectum into the posterior vaginal lumen through a weakness or defect of the rectovaginal septum (RVS)[1]. The RVS is the connective tissue fascia that separates the genital system from the digestive tract[2]. It is more firmly adherent and closely attached to the vagina than to the anorectum[3]. The thickness of the RVS varies from 0.1 mm to 2.6 mm, being thicker medially and looser and more adipose laterally[4].

Rectocele affects nearly two-thirds of parous women at variable degrees that may or may not be associated with symptoms[3]. A recent study suggested a strong association between vaginal delivery, namely the first delivery, and the development of rectocele and its size[5]. However, it was reported that nearly 12% of nulliparous women may also develop rectocele secondary to congenital defects[6].

The pathogenesis of rectocele is multifactorial including a variety of modifiable and non-modifiable factors that result in loss of integrity of the RVS and the development of rectocele. Non-modifiable risk factors include advanced age and genetic susceptibility whereas the modifiable risk factors include greater parity, history of vaginal delivery, history of pelvic surgery, obesity, level of education, constipation, and chronic increase in the intra-abdominal pressure[4].

Basically, rectoceles are based on defects in the RVS. According to Diets and Steensma[7], vaginal delivery leads to increased prevalence and size of already present, asymptomatic defects in the RVS. Richardson[8] suggested that the etiology of rectocele may be related to discreet defects in the RVS. The most common form of these defects is a transverse break just above the perineal body.

Further factors that may contribute to the development of rectocele include the loss of natural fixation that impairs the ability of the posterior wall to resist pressures from behind[8]. In addition, long-standing denervation of the pelvic floor and widening of the genital hiatus during delivery may worsen the condition[9]. Also, the change in orientation of the levator ani muscles, which are important elements in vaginal support, in response to birth trauma can contribute to the pathogenesis of rectocele. It was observed that the levator ani muscles are stretched more than 200% beyond the threshold for stretch injuries during the second stage of labor[10].

Rectocele usually presents with many symptoms that may not be constant and may vary from day to day. These symptoms include pelvic pain or feeling of pressure, feeling of the posterior vaginal bulge, manifestations of obstructed defecation syndrome (ODS), constipation, and dyspareunia[11]. Physical examination includes both rectal and vaginal assessment. Rectocele can be graded according to the Baden-Walker system, which measures the distance of the most distal point of the prolapsed wall from the hymen during Valsalva maneuver[12]. To ensure better accuracy and reliability, the POP quantification system is used to assess the rectocele with a two-point assessment method followed by grading[13].

Fluoroscopic defecography is usually used for the anatomical assessment of rectocele. It involves the introduction of a contrast medium into the rectum and the assessment of the anatomy and function at rest and during straining using an X-ray machine and a special commode[14]. It is worthy to note that up to 93% of healthy, asymptomatic women were found to have a radiologic evidence of rectocele in fluoroscopic defecography. Therefore, the indication for surgical treatment of rectocele should be predominantly based on clinical symptoms and not just the radiologic evidence of an anatomical rectocele.

More superior to X-ray defecography is the dynamic magnetic resonance imaging defecography that can confer more detailed diagnosis and can easily reconstruct the sequence of images into a video to assess the condition more precisely[15]. Also, endoanal ultrasonography dynamic scan (echodefecography) and transperineal ultrasonography are used successfully in the assessment of rectocele, perineal body, and anal sphincters[16,17].

Non-surgical management of rectocele involves eating a high-fiber diet, increasing water intake, and stool softeners. In addition, pelvic floor physiotherapy, such as Kegel exercises, is used to improve rectocele symptoms, but they appear to be more successful in anterior compartment prolapse[18]. Vaginal pessaries have been used with good results and succeed to avoid surgery in nearly two-third of patients[19].

Surgical management of rectocele is reserved for those who fail to improve after conservative treatment[20]. Surgery aims at correcting the anatomy and strengthening the rectal wall as well as correcting any coexisting pathology. Rectocele repair can be achieved through transvaginal, transperineal, transanal, or abdominal approaches. Transvaginal repair is the most common and preferable approach to gynecologists, while transanal and transperineal repairs are the preferable approaches to coloproctologists[3]. The transabdominal approach, namely ventral mesh rectopexy, is mainly indicated for high-level rectoceles, rectoceles associated with internal rectal prolapse, and/or descending perinium syndrome, associated genital prolapse, or when transperineal and transvaginal repairs are contraindicated[3,20].

The transperineal approach may have an advantage over the transvaginal and transanal approaches in that it does not involve the vaginal mucosa and does not induce stretching of the anal sphincter muscles and therefore does not compromise sexual functions or the continence mechanism[21].

The procedure is usually done under spinal anesthesia. Patients are placed in the lithotomy position, and the buttocks are separated. A curvilinear incision is made between the anal verge and the posterior fourchette to allow for proper dissection of rectovaginal space anterior to the anal sphincter complex. Using a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, with the help of digital palpation, the separation of vaginal mucosa from the rectal wall is achieved taking care to avoid injury of the vagina and rectum. The dissection is continued until the rectocele bulge is fully exposed. Then, plication of the RVS is performed in a side-to-side manner with interrupted absorbable sutures. The transperineal approach is usually combined with levatorplasty to restore the normal vaginal hiatus. Anal sphincteroplasty can be also performed in case of sphincter defects. After adequate hemostasis, perineorrhaphy is performed, and the skin is closed with interrupted absorbable sutures[22].

This was a comprehensive literature review in which an organized literature search was completed using the following keywords “rectocele,” “anterior rectocele,” “perineal repair,” “transperineal repair,” “pelvic organ prolapse,” “transperineal approach,” and “rectocele repair.” Eligible studies were identified by searching PubMed/Medline database and Google Scholar in addition to manual search of reference lists of retrieved studies. The search process started from January 1991 through December 2020.

The inclusion criteria comprised prospective or retrospective case series and cohort studies and randomized clinical trials that reported the outcome of classical transperineal rectocele repair and its technical modifications with at least 6 mo of follow-up. We excluded irrelevant studies, studies assessing techniques for rectocele repair other than the transperineal repair, studies that did not report the outcome of transperineal repair clearly, and articles without an English full text.

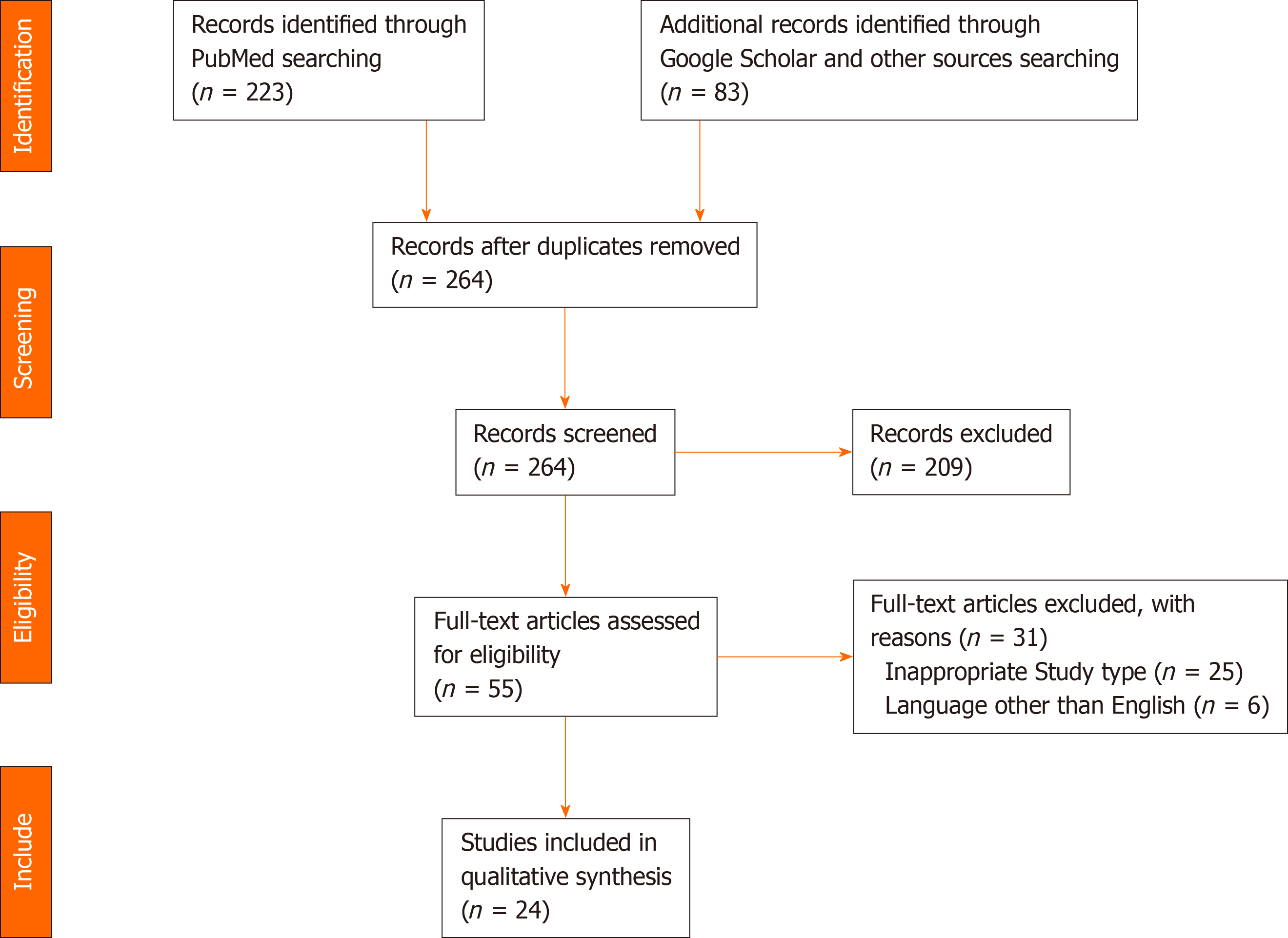

The preliminary search yielded 306 articles. After duplicates subtraction, 264 articles were initially screened. After screening, we excluded irrelevant studies, other study types (review articles, case reports, letters, and conferences papers), and articles in languages other than English, and finally 24 studies were eligible for analysis. The studies included were 13 retrospective studies, 7 prospective studies, and 4 randomized trials. The literature search and study selection process are outlined in Figure 1.

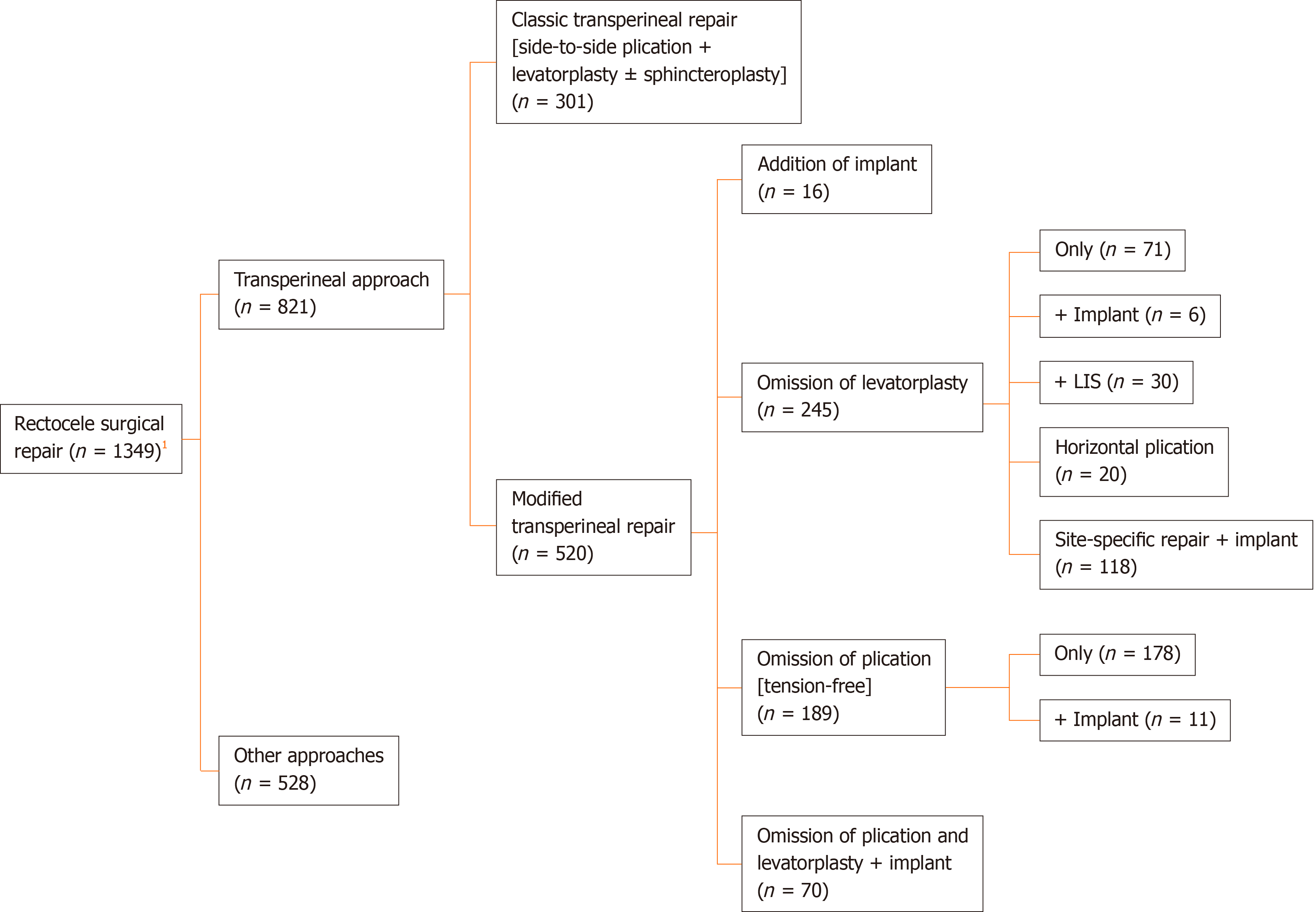

The 24 studies included 1349 patients, 821 (60.9%) of whom underwent TPR of rectocele, either using the classic repair or modified repair techniques as shown in Figure 2.

A total of 301 patients from nine studies underwent the classical TPR of rectocele. The average age of the patients ranged from 43.2-63.3 years, and the mean follow-up duration ranged from 6-48 mo (Table 1).

| Ref. | Methodology | n | Age | Follow-up | Diagnosis and assessment | Outcome | Complications |

| Balata et al[23], 2020 (Egypt) | RCT | 32 (entire cohort n = 64) | 45.1 ± 3.5 | 12 mo | Wexner constipation score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM; PISQ-12; Satisfaction | Significant improvement (decline) in Wexner score (Pre = 18.3 ± 0.7, PO = 7.2 ± 1.4, P < 0.0001) | Complications (n = 6); Dyspareunia (Pre = 11, PO =13, P = 0.8); Recurrence (n = 2) |

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 4.6 ± 0.8 cm, PO = 1.4 ± 0.9 cm, P < 0.0001) | |||||||

| Significant rise of MRP (Pre = 60.7 ± 8.5 mmHg, PO = 67.1 ± 4.2 mmHg, P = 0.0003) | |||||||

| Significant rise of MSP (Pre = 136.4 ± 3.5 mmHg, PO = 141.2 ± 2.1 mmHg, P < 0.0001) | |||||||

| Significant improvement (decline) in PISQ-12 score (Pre = 26.4 ± 2.1, PO = 18.2 ± 0.7, P < 0.0001) | |||||||

| Sexual satisfaction (Pre = 23 patient, PO = 24 patient, P = 0.8) | |||||||

| Emile et al[24], 2020 (Egypt) | Retrospective case series | 46 | 43.2 ± 10.7 | 13.9 mo (12.0-18.0) | Wexner constipation score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Significant improvement (n = 30), no improvement (n = 16) | Wound dehiscence (n = 6), hematoma (n = 2) |

| Significant improvement (decline) in Wexner score (Pre = 17.8 ± 2.7, PO = 9.2 ± 4.7, P < 0.001) | |||||||

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 4.7 ± 1.2, PO = 2.2 ± 1.4, P < 0.001) | |||||||

| Significant improvement (decline) in rectal sensation volumes | |||||||

| Tomita et al[25], 2012 (Japan) | Prospective case series | 12 | 63.3 (33.0-82.0) | 24 mo | Symptom assessment; Fluoroscopic defecography | Symptom improvement [excellent (n = 6 patient), good (n = 4 patient), fair (n = 2 patient)] | Wound infection (n = 2) |

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 4 ± 0.8 cm, PO = 0.2 ± 0.5 cm, P <0.001) | |||||||

| Complete resolution of rectocele (n = 10 patient) | |||||||

| Mills[26], 2011 (South Africa) | Retrospective case series | 117 | 24-85 | 6 mo (at least) | Symptom assessment; Trans-labial US; Rectocele wall thickness by Harpenden Skinfold Caliper (n = 50 patient); Trans-illumination (n = 50 patient) | Negative trans-illumination immediately after repair (n = 50 patient) | Wound infection (n = 2) |

| Rectocele wall thickness increased from 2.4 mm to 4.8 mm immediately after repair (n = 50 patient) | |||||||

| No PO manifestations of FI (n = 109 patient) | |||||||

| Patients with combined ODS and FI became normal (n = 43 patient) | |||||||

| Farid et al[27], 2010 (Egypt) | RCT | 16 (entire cohort n = 47) | 48.4 ± 12.6 | 6 mo | Modified ODS score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Significant improvement (decline) in modified ODS score (Pre = 17.3 ± 5.1, PO = 3.8 ± 1.7, P < 0.0001) | Wound infection (6.4%) |

| Significant reduction in rectocele depth (Pre = 4.2 ± 0.8 cm, PO = 0.9 ± 0.7 cm, P < 0.0001) | |||||||

| Significant improvement in rectal sensation volumes; Non-significant decline of dyspareunia (Pre = 6 patients, PO = 3 patients) | |||||||

| Complete rectal evacuation (n = 13 patient) | |||||||

| Significant correlation between rectocele depth and ODS score (P = 0.01) | |||||||

| Puigdollers et al[28], 2007 (Spain) | Prospective cohort | 24 (entire cohort n = 35) | 52 (28-79) | 12 mo | Questionnaire based on ROME-II criteria (Y/N) | Significant decline in PO score (Pre = 4.2, PO = 1.9, P < 0.0001) | Hematoma (n = 2) |

| Improvement: complete improvement [no symptoms] (42.9%), partial improvement [only one symptom] (5.7%), partial improvement [with ≥ 2 symptom] (31.4%), unchanged (20%) | |||||||

| Improvement of constipation (n = 11 patient) | |||||||

| Results were worse after hysterectomy | |||||||

| Hirst et al[29], 2005 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective cohort | 33 (entire cohort n = 82) | 51, median (25-83) | NP | Clinical assessment; Satisfaction assessment | Surgery outcome: All patients: Cured (n = 21 patient), initial improvement (n = 5 patient), no improvement (n = 7 patient), further surgery (n = 8 patient) | Complications (n = 0); Recurrence (n = 5) |

| Patients with rectocele only (n = 6 patients): Cured (n = 5), initial improvement (n = 1), further surgery (n = 0) Satisfaction: (n = 26) | |||||||

| Ayabaca et al[30], 2002 (Italy) | Retrospective cohort | 11 (entire cohort n = 60) | 56 (21-70) | 48 mo (9-122) | Symptom assessment; FI score; ARM | ODS symptoms improvement: Improved (n = 8 patient), lost to follow-up (n = 3 patient) | Urine retention (10%), wound dehiscence (6.6%), wound infection (n = 3.3%), other complications (10%); Recurrence: n = 0 |

| FI score improved (declined: Pre = 4.9 ± 0.9, PO = 4.2 ± 0.8); Non-significant decline in MRP and MSP in patients with FI | |||||||

| No improvement of FI (n = 1 patient) | |||||||

| Van Laarhoven et al[31], 1999 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective cohort | 10 (entire cohort n = 22) | 48 (31-63) | 27 mo, median (5-54) | Symptom assessment; Fluoroscopic defecography; Pudendal nerve motor latency | Ability to evacuate rectum: Improved (72.7%), unchanged (22.7%), deteriorated (4.5%) | Wound infection (9.1%) |

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 2.9 cm, PO = 1.7 cm, P < 0.01) | |||||||

| Significant decline in rectocele area (Pre = 7.8 cm, PO = 4.3 cm, P < 0.01) | |||||||

| No correlation between rectocele reduction and symptoms improvement |

The median rate of postoperative improvement in ODS symptoms was 72.7% (range, 45.8%-83.3%)[23-31]. More specifically, a significant decline in the symptom score used to measure ODS symptoms ranged from 54.8%-78.0%[23,24,27,28]. The studies that used fluoroscopic defecography for assessment reported a reduction in rectocele depth ranging from 41.4%-95.0%[23-25,27,31]. In regard to changes in the continence state, Mills[26] reported an improvement in fecal incontinence in all patients during follow-up, including patients with combined ODS and fecal incontinence who reported significant improvement in both complaints.

Anal pressure and sensation assessment of the patients showed variable results. According to Balata et al[23], there was a significant increase in the maximum resting pressure (MRP) and maximum squeeze pressure after TPR. In contrast, Ayabaca et al[30] reported a non-significant decline in the MRP and maximum squeeze pressure after repair. Two studies reported a significant decrease in the threshold of rectal sensation after TPR[24,27].

Patient satisfaction with the procedure was not commonly assessed in the literature. Balata et al[23] documented a significant improvement in the 12-Item POP/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire score. Also, they reported a non-significant improvement in sexual satisfaction and a decreased incidence of dyspareunia at 12 mo after repair[23]. Another study[27] reported an improvement in dyspareunia reaching up to 50%, whereas Hirst et al[29] reported satisfaction in 78.8% of their patients.

Farid et al[27] reported a correlation between the reduction in rectocele size and the improvement in ODS symptoms, in contrast to another study that failed to find significant correlation between the two parameters[31]. Overall, recurrence of rectocele was recorded in 7 (2.3%) patients after TPR, and the rates of recurrence ranged from 6.3%-15.2% across the studies reviewed[23,29]. Complications developed in 43 (14.3%) patients, and the most common complication of TPR was wound infection. Other complications included wound dehiscence, hematoma, and urine retention[23-31].

Insertion of implant with or without performing the classical repair: Six studies including 86 patients inserted an implant to reinforce the RVS, with or without performing the classical TPR. The average age of patients ranged from 50.0-58.7 years, and the average follow-up ranged from 9-29 mo (Table 2).

| Ref. | Methodology | Technique | n | Age | Follow-up | Diagnosis and Assessment | Outcome | Complications |

| Ellis[32], 2010 (United States) | Retrospective cohort | TPI [porcine intestinal submucosal collagen implant (Surgisis®)] ± SP | 32 (entire cohort n = 120) | 58.7 ± 8.9 | 12 mo | BBUSQ-22 | Improvement of BBUSQ-22 individual items (total improvement 30.9%): Significant improvement (decline) in 6 items | Urine retention (n = 2), Recurrence (n = 0) |

| Significant deterioration (raise) in pain with bowel movements | ||||||||

| Non-significant changes in 2 items | ||||||||

| Smart and Mercer-Jones[33], 2007 (United Kingdom) | Prospective case series | TPI [porcine dermal collagen implant (Permacol®)]> Suction drain (last 8 patients) | 10 | 51, median (33-71) | 9 mo, median (5-16) | Watson score | All patients (100%) had improvement in 2 or more symptoms, and 70% in three or more | Hematoma (n = 2) |

| Decline of Watson score (Pre = 10.5, PO = 4.5) | ||||||||

| Hirst et al[29], 2005 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective cohort | TPR + LP + Implant | 7 (entire cohort n = 82) | 51, median (25-83) | NP | Clinical assessment | Surgery outcome: cured (n = 5 patient), initial improvement (n = 1 patient), no improvement (n = 1 patient), further surgery (n = 2 patient); Satisfaction: n = 6 patient | Mesh erosion (n = 1); Recurrence (n = 1) |

| Mercer-Jones et al[34], 2004 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective case series | TPI ± SPProlene mesh (n = 14),Prolene + PGA mesh [Vypro II®] (n = 8) | 22 | 53, median (28-66) | 12.5 mo (3.0-47.0) | Watson score | Decline in Watson score (Pre = 11.1, PO = 3.9); Significant (P < 0.05) symptomatic improvement (n = 20 patient) | Wound infection (n = 2), wound infection and dehiscence (n = 1), dyspareunia (n = 1) Recurrence (n = 1) |

| Subjective outcome (P < 0.05) in favor of Vypro II® mesh: Moderate to excellent [Prolene (n = 9 patient), Vypro II® (n = 8 patient)] | ||||||||

| Poor [prolene (n = 5 patient), Vypro II® (n = 0 patient)] | ||||||||

| Azanjac and Jorovic[35], 1999 (Serbia) | Prospective case series | TPI [prolene mesh (Atrium®)] | 6 | 56 (46-68) | 11 mo (7-18) | Symptom assessment; Satisfaction assessment | Successful rectal evacuation without digitation (n = 6 patient); Symptom improvement [markedly (n = 2 patient), completely (n = 4 patient)] | Urine retention (n = 1) |

| Satisfaction [very satisfied (n = 5 patient), somewhat (n = 1 patient)] | ||||||||

| Watson et al[36], 1996 (United Kingdom) | Prospective case series | TPR + LP + Implant [prolene mesh (Marlex®)] | 9 | 50, median (32-61) | 29 mo, median (8-36) | Watson scoreFluoroscopic defecography | Significant decline in PO score (Pre = 11.7, PO = 1.9, P < 0.05); No further need for digital evacuation (n = 8); Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 3.7, PO = 2.4, P < 0.05) | Wound infection (n = 1); Dyspareunia: Resolved (n = 1), abstained (n = 2), acquired (n = 1) |

| Significant decline in barium trapping (Pre = 14%, PO = 5%, P < 0.005) |

When the classical repair was omitted and an implant only was inserted the median improvement in ODS was 90.9% (range, 70%-100%)[32-35]. A significant drop in ODS score was reported in 30.9%-64.9% of patients[32-34], and significant satisfaction was reported by 83.3% of the patients according to Azanjac and Jorovic[35].

On the other hand, when a synthetic mesh implant was inserted to reinforce the classical transperineal repair, the improvement in ODS ranged from 71.4%-88.9% with a median of 80.1%[29,36]. Watson et al[36] reported a reduction in rectocele size and barium entrapment equal to 35.1% and 64.3%, respectively[36], and Hirst et al[29] reported complete or partial satisfaction in 85.7% of patients.

Mercer-Jones et al[34] compared two types of meshes, polypropylene mesh and composite mesh of polypropylene and polyglycolic acid. The authors reported better outcome with the composite mesh, reaching 100% as compared to 64.3% with polypropylene mesh. New-onset dyspareunia was reported after both techniques[34,36]. Additionally, Watson et al[36] reported improvement in dyspareunia in 1 patient and persistence of symptoms in another 2 patients[36].

Overall, only two rectocele recurrences (2.3%) were reported after insertion of mesh implant[29,34]. Twelve (13.9%) patients developed complications. The most common reported complication was wound infection, whereas the most serious complication was mesh erosion, reported in 1.1% of patients[29]. Other complications included wound dehiscence, hematoma, and urine retention[32-36].

Omission of levatorplasty: Seven studies including 245 patients performed the classical TPR without performing levatorplasty. The average age of patients ranged from 41.4-52.0 years, and the mean follow-up ranged from 6-54 mo (Table 3).

| Ref. | Method-ology | Technique (TPR) | n | Age | Follow-up | Diagnosis and assessment | Outcome | Complications |

| Omar et al[37], 2020 (Egypt) | Pilot RCT | Omission of levatorplasty only (n = 20) HP instead of classical plication (n = 20) | 40 | 44.9 (± 7.7) | 12 mo | Wexner constipation score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Cure rate: Complete cure: TPR (n = 13 patient), HP (n = 11 patient) | TPR [wound dehiscence (n = 3), bleeding (n = 1), recurrence (n = 3)], HP [wound dehiscence (n = 1), bleeding (n = 1) recurrence (n = 1)] |

| Significant improvement TPR (n = 6 patient), HP (n = 8 patient) | ||||||||

| No improvement TPR (n = 1 patient), HP (n = 1 patient) | ||||||||

| Comparable significant improvement (decline) in Wexner score in both | ||||||||

| More decline in rectocele depth with HP [TPR = 2.6 ± 0.5 cm, HP = 1.7 ± 0.5 cm, P < 0.0001] | ||||||||

| More improvement of dyspareunia with HP [TPR = 9 patient, HP = 2 patient, P = 0.03] | ||||||||

| Sari et al[38], 2019 (Turkey) | Retrospective cohort | Omission of levatorplasty only (n = 6)+ Implant [prolene mesh without fixation (n = 6)] | 12 (entire cohort n = 78) | 52 (31-88) | 54 mo (3-218) | Symptom assessment Fluoroscopic defecography | Patients free of symptoms (78.2%) | Wound infection (3.8%), bleeding (2.6%); Recurrence (n = 0) |

| Patients had remaining urinary or defecatory symptoms or PO pain (21.8%) | ||||||||

| Lisi et al[39], 2018 (Italy) | Prospective case series | SSR + Implant [porcine dermal collagen implant (Permacol®)] | 25 | 47 (30-62) | 12-24 mo | Watson score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARMSF-36 | No complaint regarding bowel functions at 2 mo and no sexual problemsSignificant decline in Watson score (Pre = 9.9 ± 2.5, PO = 2.1 ± 0.3, P < 0.0001) | UTI (n = 2), delayed wound healing (n = 4), Recurrence (n = 3) |

| All PO rectocele depths were < 2 cm | ||||||||

| Non-significant rise in MRP and MSP | ||||||||

| Non-significant improvement of both composites of SF-36 | ||||||||

| Youssef et al[40], 2017 (Egypt) | RCT | Omission of levatorplasty only (n = 30)+ LIS (n = 30) | 60 | 41.4 (17.0-70.0) | 17.8 mo (6.0-36.0) | Wexner score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARMPAC-QOL | Complete clinical improvement 70% (TPR) vs 93.3% (TPR + LIS) | TPR [ecchymosis (n = 1), wound dehiscence (n = 2), dyspareunia (n = 1), recurrence (n = 3)] |

| More decline in Wexner score with addition of LIS (TPR = 11.1 ± 2.1, TPR + LIS = 8 ± 2, P < 0.0001) | TPR + LIS [wound infection (n = 1), wound dehiscence (n = 3), FI (n = 2), dyspareunia (n = 1), recurrence (n = 1)] | |||||||

| More satisfaction with TPR + LIS | ||||||||

| Score: (TPR = 11.4 ± 2.7, TPR + LIS = 12.9 ± 2.3, P = 0.02); n of patients: (TPR = 21 patient, TPR + LIS = 28 patient, P = 0.04) | ||||||||

| More improvement (decline) in MRP with TPR + LIS (TPR = 87.5 ± 5.1 mmHg, TPR + LIS = 74.4 ± 3.5 mmHg, P < 0.0001) | ||||||||

| Farid et al[27], 2010 (Egypt) | RCT | Omission of levatorplasty only | 15 (entire cohort n = 47) | 48.4 ± 12.6 | 6 mo | Modified ODS score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Significant improvement (decline) in ODS score (Pre = 16.4 ± 6.3, PO = 7.7 ± 2.5, P < 0.001) | Wound infection (6.4%) |

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 3.8 ± 1 cm, PO = 0.9 ± 0.8 cm, P < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Significant improvement in rectal sensations | ||||||||

| Decline of dyspareunia (Pre = 6 patient, PO = 5 patient) | ||||||||

| Complete rectal evacuation (n = 10 patient) | ||||||||

| Significant correlation between rectocele depth and ODS score (P = 0.001) | ||||||||

| Milito et al[41], 2010 (Italy) | Retro-spective case series | SSR + Implant [porcine dermal collagen implant (Permacol®)] | 10 | 47.7 (25.0-70.0) | 2-20 mo | Watson score; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARMSF-36 | Significant decline in Watson score (Pre = 9.6 ± 1.8, PO = 1.6 ± 0.6, P < 0.0001) | UTI (n = 1), delayed wound healing (n = 1); Recurrence (n = 2) |

| Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 3.8 cm, PO < 2 cm, P < 0.0001) | ||||||||

| Prospective case series | SSR + Implant [PGA mesh (Soft PGA Felt®)] | 83 | 49, median (29-56) | 14 mo, median (6-36) | Watson score; Fluoroscopic defecography (n = 55); POP-Q | Significant improvement of Watson score (Pre = 9.9 ± 1.9, PO = 1.6 ± 0.6, P < 0.0001) | Bleeding (n = 3), wound infection (n = 4), dyspareunia (n = 8); Recurrence (NP) | |

| Subjective cure rate (n = 83 patient); PO rectocele depth < 2cm (n = 21 patient) | ||||||||

| At 6m, anatomical cure (n = 74 patient), POP-Q stage II (n = 9 patient), at 14 m, POP-Q stage II (n = 10 patient) | ||||||||

| Would redo surgery if symptoms recur (n = 80 patient) |

Omission of levatorplasty only (n = 71): The omission of levatorplasty resulted in postoperative improvement in ODS symptoms in 66.7%-78.2% of patients[27,37,38-40]. The reduction in ODS scores ranged between 32.8% and 53.0%[27,37,40]. A significant reduction in rectocele size was recorded in 45.8%-76.3% of patients[27,37]. Youssef et al[40] reported an increase in MRP, in contradiction to another study that reported a decrease in anal pressures[40]. Satisfaction was reported in 70% of patients[40]. Two studies reported an improvement in dyspareunia in 16.7%-35.7% of patients[27,37], whereas another study documented de novo dyspareunia[40]. Two studies reported recurrence rates ranging between 10% and 15%, whereas Sari et al[38] did not report any recurrence. Complications included wound dehiscence, wound infection, bleeding, and hematomas[27,37,38,40].

Addition of implant (n = 6): Only a small number of patients had a synthetic implant along with omission of levatorplasty. There were not differential results from the entire cohort. The rate of improvement in ODS symptoms after this technique was 78.2%, and the rate of complications was 6.4% with no reported recurrence[38].

Addition of limited internal sphincterotomy (LIS) (n = 30): Only one study[40] combined LIS with transperineal repair in patients with type-I anterior rectocele associated with high resting pressure. This technique resulted in a greater improvement in ODS symptoms in 93.3% of patients as compared to 70.0% when LIS was not performed. Also, the quality-of-life score was better in patients with concomitant LIS than in patients without LIS (12.9 vs 11.4, P = 0.02, respectively). Obviously, lower MRP was recorded after LIS as compared to patients without LIS (74.4 mmHg vs 87.5 mmHg, P < 0.0001). Complications included fecal incontinence in 2 patients and new-onset dyspareunia in 1 patient. Only 1 patient experienced recurrence of rectocele at 12 mo after TPR combined with LIS.

Horizontal plication (n = 20): Omar et al[37] replaced the classical vertical plication of the RVS with craniocaudal or horizontal plication. Although the rate of complete cure of rectocele after horizontal plication was lower than the classical plication (55% vs 65%), the postoperative constipation scores were comparable. Horizontal plication managed to confer a more significant reduction in rectocele size, more improvement in dyspareunia, and lower recurrence rate than the classical repair.

Site-specific repair with an implant (n = 118): Replacement of the classical repair with site-specific repair along with the insertion of implants resulted in a greater improvement in ODS symptoms, reaching up to 100%. The improvement in Watson score ranged from 78.8% up to 83.8%. Additionally, three studies[39,41,42] that used site-specific repair reported a significant reduction in rectocele size. Leventoğlu et al[42] used POP quantification to assess postoperative anatomic correction. At 6 mo after surgery, 10.8% remained POP quantification stage II, which then increased to 12% at 14 mo. Lisi et al[39] reported a non-significant increase in anal pressures. Two studies reported normal sexual functions in sexually active patients[39,41], while another study reported postoperative dyspareunia in 9.6% of patients[42]. Two studies used the 36-Item Short Form Survey to assess the quality of life with non-significant increase in both composites of the tool[39,41]. Leventoğlu et al[42] reported that 96.4% of the patients were satisfied and would redo the surgery if the symptoms recurred. Two studies reported recurrence in 16%-20% of patients[39,41]. Complications were delayed wound healing, wound infection, urinary tract infection, and bleeding[39,41,42].

Omission of RVS plication: In five studies comprising 189 patients, plication of the RVS was not done, and only levatorplasty or implant insertion was done. The average age of patients ranged from 52.1-59.0 years, and the average follow-up ranged from 14-42 mo (Table 4).

| Ref. | Methodology | Technique | n | Age | Follow-up | Diagnosis and assessment | Outcome | Complications |

| Fischer et al[43], 2005 (Germany) | Retrospective cohort | TPLP | 10(entire cohort n = 36) | 59 (30-79) | 36 mo (8-110) | Symptom assessment; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Symptom improvement (cured): n = 9 patientAll patients (n = 7) showed improvement in FI | RVF (n = 1), wound infection (n = 1), dyspareunia (n = 1) |

| 3 out of 6 patients showed no rectocele with defecography | ||||||||

| Non-significant rise of both MRP and MSP | ||||||||

| Satisfaction with functional outcomes: n = 9 patient | ||||||||

| Boccasanta et al[44], 2001 (Italy) | Retrospective cohort | TPLP (addition of prolene mesh in 2 patients) | 126(entire cohort n = 317) | 52.4 (28.0-80.0) | 22.8 – 27.5 mo | Symptom assessment; Fluoroscopic defecography; ARM | Outcome (n = 110 patient) at 12 m: excellent (n = 45 patient), fair (n = 58 patient), poor (n = 7 patient) | Vaginal stenosis (n = 2) |

| PO defecography: complete absence (44.1%), residual (55.9%); Non-significant rise of both MRP and MSP | ||||||||

| Lamah et al[45], 2001 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective case series | TPLP ± SP> suction drain | 44 | 57.5 (35.0-82.0) | 42 mo (6-84) | Symptom assessment; Continence assessment; Sexual function assessment; Satisfaction assessment | Symptom assessment: TPLP (n = 33 patient): improvement of lump sensation (n = 28 patient), improvement of defecation (n = 29 patient); TPLP + SP (n = 11 patient): improvement of one or both (n = 8 patient) | Wound infection (n = 2), deteriorated FI (n = 1), dyspareunia (n = 2) |

| Continence (n = 11 patient): at Pre [continent (n = 0), incontinent (n = 11)], at 12 mo [continent (n = 5), incontinent (n = 6)], at 24 mo [continent (n = 3), incontinent (n = 8)], > 36 mo [continent (n = 3), incontinent (n = 8)] | ||||||||

| Sexual function: TPLP [Improved (n = 8), unchanged (n = 9), deteriorated (n = 2), declined (n = 10)]; TPLP + SP [Improved (n = 2), unchanged (n = 2), deteriorated (n = 0), declined (n = 5)] | ||||||||

| Satisfaction (satisfied / total): TPLP [at 2 yr: (n = 30/33), at 3.2 yr (n = 21/24)]; TPLP + SP [at 2 yr (10/11), at 3.2 yr (6/11)] | ||||||||

| Van Laarhoven et al[31], 1999 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective cohort | TPI + LP [prolene mesh (Marlex®)] | 5 (entire cohort n = 22) | 52.1 (31.0-81.0) | 27 mo, median (5-54) | Symptom assessmentFluoroscopic defecographyPudendal nerve motor latency | Ability to evacuate rectum: improved (72.7%), unchanged (22.7%), deteriorated (4.5%); Significant decline in feeling of incomplete evacuation (Pre = 86.4%, PO = 45.5%, P = 0.01); Significant decline in rectocele depth (Pre = 2.9 cm, PO = 1.7 cm, P < 0.01); Significant decline in rectocele area (Pre = 7.8 cm, PO = 4.3 cm, P < 0.01); No correlation between rectocele reduction and symptoms improvement | Wound infection (9.1%) |

| Parker and Phillips[46], 1993 (United Kingdom) | Retrospective case series | TPI + LP [prolene mesh (Marlex®)] | 4 | 42-65 | 14 mo (6-18) | Symptom assessment | Successful rectal evacuation without digitation (n = 3), digitation occasionally (n = 1); Satisfaction (n = 4) | NP |

Transperineal levatorplasty (n = 178): This modification resulted in improvement of ODS symptoms in 87.9% to 93.6% of patients[43-45] with lower rates of improvement (72.7%) observed when sphincteroplasty was added to treat coexisting fecal incontinence[44]. Reduction in the rectocele size ranged between 44.1%-50.0%[43,44]. According to two studies, there were non-significant increases in both MRP and maximum squeeze pressure[43,44]. The incidence of continence improvement reached 100% in one study[43]. Satisfaction ranged between 87.5% and 90.0%[43,45], while in patients with baseline fecal incontinence, satisfaction rates were 91% at 12 mo and 54.5% at 36 mo postoperatively[45]. The most serious complication was rectovaginal fistula, and other complications were mostly wound infection[43-45].

Transperineal implant with levatorplasty (n = 11): Only a small number of patients underwent this technique[31,44,46]. Two cohort studies did not report differential results of subgroups[31,44]. Parker and Phillips reported successful rectal evacuation in 75% of patients, and all patients were satisfied with the procedure. No complications were recorded[46].

Three studies used the transperineal approach as an auxiliary procedure for the main approach. D’Hoore et al[47] performed laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy combined with TPR to facilitate proper mesh placement in large rectoceles[47]. Altomare et al[48] adopted the transanal approach and used a circular stapler to repair rectoceles. The combination with transperineal approach helped proper placement of rectal wall into the stapler with sparing of the vaginal wall[48]. Finally, Boccasanta et al[44] combined transperineal levatorplasty with different transanal procedures including Block’s obliterative suture, Sarles’ procedure, and stapled mucosectomy to augment the repairs.

The transperineal repair of rectocele is associated with satisfactory, yet variable, rates of improvement in ODS symptoms with a parallel increase in quality-of-life score. Several modifications of the classical TPR are described. These modifications include omission of levatorplasty, insertion of implants, performing LIS, changing the direction of classical plication, and site-specific repair. The indications for these modifications are not yet fully clear and need further prospective studies to help tailor the technique to rectocele patients.

One of the important modifications of TPR is the insertion of mesh implant to reinforce the repair of the RVS. The insertion of mesh implant along with TPR appeared to reduce the recurrence of rectocele significantly, down to less than 5%, with acceptably low complication rates that mostly comprised of wound infections. Mesh-related complications such as erosion were reported only once after TPR[29]. In contradiction, the Food and Drug Administration has recommended stopping the use of mesh implants to augment transvaginal repair because the agency did not receive sufficient evidence to assure that the potential benefits of mesh implants outweigh their probable risks that include mesh fistulation and erosion[49].

The present review has a few limitations that include the small number of studies that assessed the outcome of transperineal repair of rectocele, namely those describing technical modifications. The heterogeneity of data reported in the studies precluded the conduction of a formal meta-analysis of the success and complications of the procedure. Further randomized trials comparing transperineal repair to other repair techniques would add more evidence on the efficacy of this approach.

The transperineal repair of rectocele is associated with satisfactory, yet variable, improvement in ODS symptoms with a parallel increase in quality-of-life score. Several modifications of the classical TPR were described. These modifications include omission of levatorplasty, insertion of implants, performing lateral sphincterotomy, changing the direction of classical plication, and site-specific repair. The indications for these modifications are not yet fully clear and need further prospective studies to help tailor the technique to rectocele patients.

Rectocele is a common finding in women. However; it may require surgical treatment when associated with symptoms of obstructed defecation. Transperineal repair is one of the common procedures used for rectocele repair with variable outcomes.

The variable outcomes after transperineal repair of rectocele moved us to review the current literature for different technical modifications described to improve the procedure.

To review the technique and outcomes of transperineal repair of rectocele and to investigate the different technical modifications introduced to the original technique of repair.

An organized literature search for studies that assessed the outcome of transperineal repair of rectocele was performed. PubMed/Medline and Google Scholar were queried in the period of January 1991 through December 2020.

Twenty-four studies were included to this review. Nine studies including 301 patients assessed the classical transperineal repair of rectocele. The median rate of postoperative improvement in symptoms was 72.7% (range, 45.8%-83.3%), and reduction in rectocele size ranged from 41.4%-95.0%. Modifications of the classical repair entailed omission of levatorplasty, addition of implant, concomitant lateral internal sphincterotomy, changing the direction of plication of rectovaginal septum, and site-specific repair.

The transperineal repair of rectocele is associated with satisfactory, yet variable, improvement in obstructed defecation symptoms with parallel increase in quality-of-life score. Several modifications of the classical transperineal repair were described.

The indications for the technical modifications of transperineal rectocele repair are not yet fully clear and need further prospective studies to help tailor the technique to rectocele patients.

| 1. | Mustain WC. Functional Disorders: Rectocele. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:63-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dietz HP. Can the rectovaginal septum be visualized by transvaginal three-dimensional ultrasound? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;37:348-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ladd M, Tuma F. Rectocele. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2020. |

| 4. | Dariane C, Moszkowicz D, Peschaud F. Concepts of the rectovaginal septum: implications for function and surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27:839-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dietz HP, Gómez M, Atan IK, Ferreira CSW. Association between vaginal parity and rectocele. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1479-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dietz HP, Clarke B. Prevalence of rectocele in young nulliparous women. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;45:391-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dietz HP, Steensma AB. The role of childbirth in the aetiology of rectocele. BJOG. 2006;113:264-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Richardson AC. The anatomic defects in rectocele and enterocele. J Pelvic Surg. 1995;1:214-221. |

| 9. | Cundiff GW, Fenner D. Evaluation and treatment of women with rectocele: focus on associated defecatory and sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:1403-1421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Lien KC, Mooney B, DeLancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA. Levator ani muscle stretch induced by simulated vaginal birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:31-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 307] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iglesia CB, Smithling KR. Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96:179-185. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Baden WF, Walker TA. Genesis of the vaginal profile: a correlated classification of vaginal relaxation. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1972;15:1048-1054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Persu C, Chapple CR, Cauni V, Gutue S, Geavlete P. Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) - a new era in pelvic prolapse staging. J Med Life. 2011;4:75-81. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Palmer SL, Lalwani N, Bahrami S, Scholz F. Dynamic fluoroscopic defecography: updates on rationale, technique, and interpretation from the Society of Abdominal Radiology Pelvic Floor Disease Focus Panel. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2021;46:1312-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thapar RB, Patankar RV, Kamat RD, Thapar RR, Chemburkar V. MR defecography for obstructed defecation syndrome. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2015;25:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coura MM. The Role of Three-Dimensional Endoanal Ultrasound in Preoperative Evaluation of Anorectal Diseases. In: Proctological Diseases in Surgical Practice. Cianci P, editor. Intech Open. 2018;. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Albuquerque A, Pereira E. Current applications of transperineal ultrasound in gastroenterology. World J Radiol. 2016;8:370-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Pelvic organ prolapse: Pelvic floor exercises and vaginal pessaries. [cited 13 July 2021]. In: InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525762/. |

| 19. | Coolen AWM, Troost S, Mol BWJ, Roovers JPWR, Bongers MY. Primary treatment of pelvic organ prolapse: pessary use versus prolapse surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hall GM, Shanmugan S, Nobel T, Paspulati R, Delaney CP, Reynolds HL, Stein SL, Champagne BJ. Symptomatic rectocele: what are the indications for repair? Am J Surg. 2014;207:375-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zimmermann EF, Hayes RS, Daniels IR, Smart NJ, Warwick AM. Transperineal rectocele repair: a systematic review. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:773-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weledji EP, Eyongeta DE. How I Do It? Surgical Management of Rectocele: A Transperineal Approach. J Surg Tech Proced. 2020;4:1035. |

| 23. | Balata M, Elgendy H, Emile SH, Youssef M, Omar W, Khafagy W. Functional Outcome and Sexual-Related Quality of Life After Transperineal Versus Transvaginal Repair of Anterior Rectocele: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63:527-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Emile SH, Balata M, Omar W, Khafagy W, Elgendy H. Specific Changes in Manometric Parameters are Associated with Non-improvement in Symptoms after Rectocele Repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:2019-2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tomita R, Ikeda T, Fujisaki S, Sugito K, Sakurai K, Koshinaga T, Shibata M. Surgical technique for the transperineal approach of anterior levatorplasty and recto-vaginal septum reinforcement in rectocele patients with soiling and postoperative clinical outcomes. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:1063-1067. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mills RP. Rectocele and anal sphincter defect - surgical anatomy and combined repair. S Afr J Surg. 2011;49:182-185. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Farid M, Madbouly KM, Hussein A, Mahdy T, Moneim HA, Omar W. Randomized controlled trial between perineal and anal repairs of rectocele in obstructed defecation. World J Surg. 2010;34:822-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Puigdollers A, Fernández-Fraga X, Azpiroz F. Persistent symptoms of functional outlet obstruction after rectocele repair. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:262-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hirst GR, Hughes RJ, Morgan AR, Carr ND, Patel B, Beynon J. The role of rectocele repair in targeted patients with obstructed defaecation. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:159-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ayabaca SM, Zbar AP, Pescatori M. Anal continence after rectocele repair. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:63-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Van Laarhoven CJ, Kamm MA, Bartram CI, Halligan S, Hawley PR, Phillips RK. Relationship between anatomic and symptomatic long-term results after rectocele repair for impaired defecation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ellis CN. Outcomes after the repair of rectoceles with transperineal insertion of a bioprosthetic graft. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Smart NJ, Mercer-Jones MA. Functional outcome after transperineal rectocele repair with porcine dermal collagen implant. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1422-1427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mercer-Jones MA, Sprowson A, Varma JS. Outcome after transperineal mesh repair of rectocele: a case series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:864-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Azanjac B, Jorovic M. Transperineal repair of recurrent rectocele using polypropylene mesh. Tech Coloproctol. 1999;3:39-41. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Watson SJ, Loder PB, Halligan S, Bartram CI, Kamm MA, Phillips RK. Transperineal repair of symptomatic rectocele with Marlex mesh: a clinical, physiological and radiologic assessment of treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:257-261. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Omar W, Elfallal AH, Emile SH, Elshobaky A, Fouda E, Fathy M, Youssef M, El-Said M. Horizontal versus vertical plication of the rectovaginal septum in transperineal repair of anterior rectocele: a pilot randomized clinical trial. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:923-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sari R, Kus M, Arer I, Yabanoglu H. A Single-center Experience of Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Management for Rectocele Disease. Turk J Colorectal Dis. 2019;29:183-187. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lisi G, Campanelli M, Grande S, Grande M, Mascagni D, Milito G. Transperineal rectocele repair with biomesh: updating of a tertiary refer center prospective study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2018;33:1583-1588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Youssef M, Emile SH, Thabet W, Elfeki HA, Magdy A, Omar W, Khafagy W, Farid M. Comparative Study Between Trans-perineal Repair With or Without Limited Internal Sphincterotomy in the Treatment of Type I Anterior Rectocele: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Milito G, Cadeddu F, Selvaggio I, Grande M, Farinon AM. Transperineal rectocele repair with porcine dermal collagen implant. A two year clinical experience. Pelviperineology. 2010;29:76-78. |

| 42. | Leventoğlu S, Menteş BB, Akin M, Karen M, Karamercan A, Oğuz M. Transperineal rectocele repair with polyglycolic acid mesh: a case series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2085-2092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Fischer F, Farke S, Schwandner O, Bruch HP, Schiedeck T. [Functional results after transvaginal, transperineal and transrectal correction of a symptomatic rectocele]. Zentralbl Chir. 2005;130:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Boccasanta P, Venturi M, Calabrò G, Trompetto M, Ganio E, Tessera G, Bottini C, Pulvirenti D'Urso A, Ayabaca S, Pescatori M. Which surgical approach for rectocele? Tech Coloproctol. 2001;5:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lamah M, Ho J, Leicester RJ. Results of anterior levatorplasty for rectocele. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Parker MC, Phillips RK. Repair of rectocoele using Marlex mesh. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:193-194. [PubMed] |

| 47. | D'Hoore A, Vanbeckevoort D, Penninckx F. Clinical, physiological and radiological assessment of rectovaginal septum reinforcement with mesh for complex rectocele. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1264-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Altomare DF, Rinaldi M, Veglia A, Petrolino M, De Fazio M, Sallustio P. Combined perineal and endorectal repair of rectocele by circular stapler: a novel surgical technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1549-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Food and Drug Administration. Urogynecologyic surgical mesh implant. July 10, 2019 [cited 13 July 2021]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/urogynecologic-surgical-mesh-implants. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Surgery

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: García-Flórez LJ S-Editor: Liu M L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH