Published online Nov 27, 2021. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v13.i11.1414

Peer-review started: April 25, 2021

First decision: July 15, 2021

Revised: July 23, 2021

Accepted: September 8, 2021

Article in press: September 8, 2021

Published online: November 27, 2021

Processing time: 215 Days and 3.1 Hours

Although minimally invasive surgery is becoming more commonly applied for ileostomy reversal (IR), there have been relatively few studies of IR for patients with Crohn's disease (CD). It is therefore important to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of laparoscopy for patients with CD.

To compare the safety, feasibility, and short-term and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic IR (LIR) vs open IR (OIR) for the treatment of CD.

The baseline characteristics, operative data, and short-term (30-d) and long-term outcomes of patients with CD who underwent LIR and OIR at our institution between January 2017 and January 2020 were retrieved from an electronic database and retrospectively reviewed.

Of the 60 patients enrolled in this study, LIR was performed for 48 and OIR for 12. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, days to flatus and soft diet, postoperative complications, hospitalization time, readmission rate within 30 d, length of hospitalization, hospitalization costs, or reoperation rate after IR between the two groups. However, patients in the LIR group more frequently required lysis of adhesions as compared to those in the OIR group (87.5% vs 41.7%, respectively, P < 0.05). Notably, following exclusion of patients who underwent enterectomy plus IR, OIR was more advantageous in terms of postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function and hospitalization costs.

The safety and feasibility of LIR for the treatment of CD are comparable to those of OIR with no increase in intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Core Tip: Laparoscopic surgery has been shown to promote faster recovery, decrease postoperative pain and morbidity, and improve postoperative quality of life. For Crohn’s disease (CD) patients who require IR, laparoscopy greatly improves the rate of enterolysis and reduces the incidence of ileus. Meanwhile, laparoscopy can effectively explore the entire gastrointestinal tract to identify strictures within short segments of the small bowel, while avoiding large incisions. The aim of the present study was to compare the operative data and short-term and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileostomy reversal vs open ileostomy reversal to explore the safety and feasibility of laparoscopic ileostomy reversal for CD.

- Citation: Wan J, Yuan XQ, Wu TQ, Yang MQ, Wu XC, Gao RY, Yin L, Chen CQ. Laparoscopic vs open surgery in ileostomy reversal in Crohn’s disease: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2021; 13(11): 1414-1422

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v13/i11/1414.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v13.i11.1414

A temporary ileostomy is frequently created during low colorectal anastomosis to prevent fistula formation. After intestinal anastomosis, patients with active Crohn’s disease (CD) are at a greater risk for anastomotic fistula formation, which often requires ileostomy[1,2] to alleviate symptoms. Given the proclivity for recurrence, ileostomy reversal (IR) is limited to relatively few CD patients[3]. However, as compared with colostoma, ileostoma requires more complex care and is associated with a greater risk for complications[4]. Therefore, in the remission stage of CD, many patients consider IR. Normally, open IR (OIR) is not overly complicated. But, the varying degrees of intestinal adhesions in CD require intraoperative enterolysis[5]. In addition, with the progression of CD, the whole digestive system will inevitably become fibrotic, eventually leading to stricture[6]. Therefore, it is essential to check the whole gastrointestinal tract during IR for patients with CD.

Previous studies have shown that laparoscopic surgery promotes faster recovery, decreases postoperative pain and morbidity, and improves postoperative quality of life[5,7,8]. During open surgery for CD, surgeons often have to explore the entire gastrointestinal tract to avoid missing occult diseased segments and critical proximal strictures. Laparoscopy can effectively explore the entire gastrointestinal tract to identify strictures within short segments of the small bowel, while avoiding large incisions. Although laparoscopy has become more commonly applied in IR[9], relatively few studies have compared OIR with laparoscopic IR (LIR) for CD. It is therefore important to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of LIR in patients with CD. The aim of the present study was to compare the operative data and short-term and long-term outcomes of LIR vs OIR to explore the safety and feasibility of LIR for CD.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital Affiliated to the Tongji University School of Medicine (approval No. 21K53) and conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The cohort of this retrospective study consisted of 60 patients who underwent IR at our institution from January 2017 to January 2020. Of these 60 patients, LIR was performed for 48 and OIR for 12. The inclusion criteria were age 18-75 years and pathological confirmation of CD. All procedures were performed by two experienced laparoscopic colorectal surgeons. Standardized treatment regimens were used during the perioperative period. The following data were retrieved from the electronic database of Shanghai Tenth People’s Hospital: Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, duration of ileostomy, duration of CD, history of abdominal surgery, hematologic parameters (WBC, CRP, ESR, ALB, HB, PLT, PT, and APTT), operation time, intraoperative blood loss, enterolysis rate, days to flatus and soft diet, postoperative complications, hospitalization time, readmission rate within 30 days, length of stay, and hospitalization cost. As a long-term outcome, the reoperation rate after IR was determined by telephone interviews.

Preoperative preparation included physical examination, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasonography, and colonoscopy. Patients in the remission stage of CD were considered for IR.

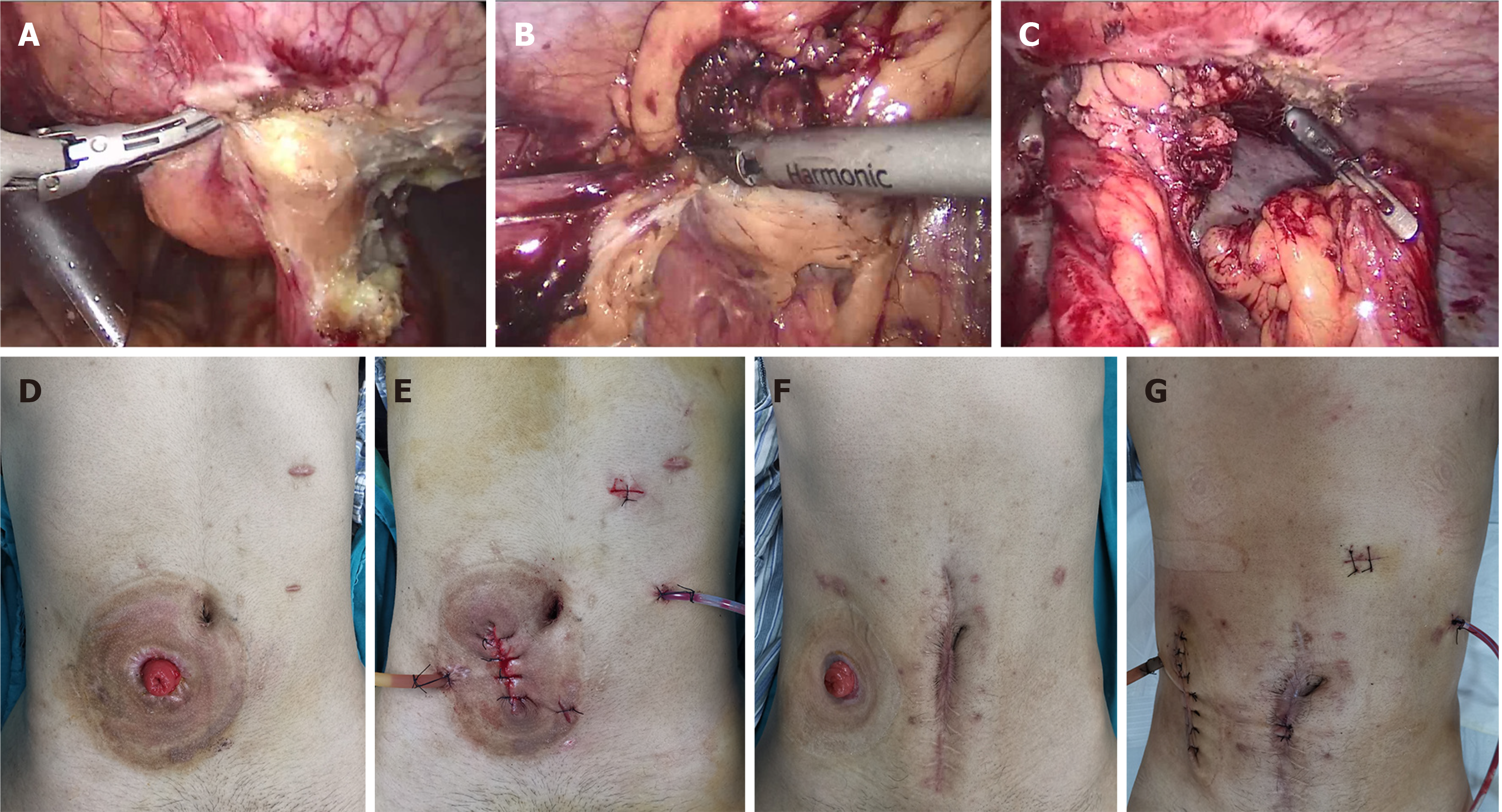

Laparoscopy was performed using the four-port method. Briefly, two transverse sites below the umbilicus were punctured with 12-mm trocars for observation, the right abdomen was punctured with a 5-mm trocar, and the left abdomen was punctured with 5- and 12-mm trocars. The entire gastrointestinal tract was explored laparoscopically to separate the intraperitoneal adhesions at the stoma and the distal intestinal stump (Figure 1A-C). Following incision of the annulus of the skin around the stoma, the stoma and distal intestinal stump were pulled out. If the bowel segment was obviously fibrotic with a stricture, strictureplasty or resection of the strictured segment was performed. The proximal and distal intestines were anastomosed side to side with auto sutures (GIA 80 mm; Medtronic plc, Dublin, Ireland). Then, the openings were closed and the anastomosis was reinforced with 3-0 absorbable sutures. For open surgery, an incision was made directly along the skin around the stoma. Then, the stoma and distal intestinal stump were separated under direct visualization. The anastomosis method was the same as that in the laparoscopic group.

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24.0. (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) and GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States). Quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± SD (range). Data were compared using the Student’s t-test and chi-squared test. A probability (P) value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were no statistically significant differences in age, gender, BMI, ASA class, duration of ileostomy, CD duration, history of abdominal operation, or hematologic examination between the LIR and OIR groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Variable | Laparoscopic (n = 48) | Open (n = 12) | P value |

| Age, yr, mean (range) | 36.5 (18-70) | 39.8 (20-73) | NS |

| Gender, male | 36 | 8 | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 20.2 ± 4.9 | 20.3 ± 2.9 | NS |

| ASA class | NS | ||

| I-II | 45 | 11 | |

| III-IV | 3 | 1 | |

| Duration of ileostomy, mo, mean ± SD (range) | 7.6 ± 6.8 (3-48) | 13.0 ± 18.5 (3-72) | NS |

| Disease duration, mo, mean ± SD (range) | 46.1 ± 48.7 (3-168) | 39.3 ± 33.5 (4-96) | NS |

| History of abdominal operation | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | NS |

| Hematologic examination | |||

| WBC (/L) | 5.2 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | NS |

| CRP (mg/L) | 5.9 ± 8.9 | 8.9 ± 17.6 | NS |

| ESR (mm) | 15.4 ± 11.5 | 15.8 ± 6.9 | NS |

| ALB (g/L) | 45.4 ± 4.8 | 43.6 ± 4.0 | NS |

| Hb (g/L) | 134.0± 18.2 | 131.0 ± 16.0 | NS |

| PLT (/L) | 240.8 ± 105.6 | 206.3 ± 49.3 | NS |

| PT (s) | 11.5 ± 0.9 | 11.2 ± 0.8 | NS |

| APTT (s) | 29.3 ± 3.4 | 28.2 ± 4.0 | NS |

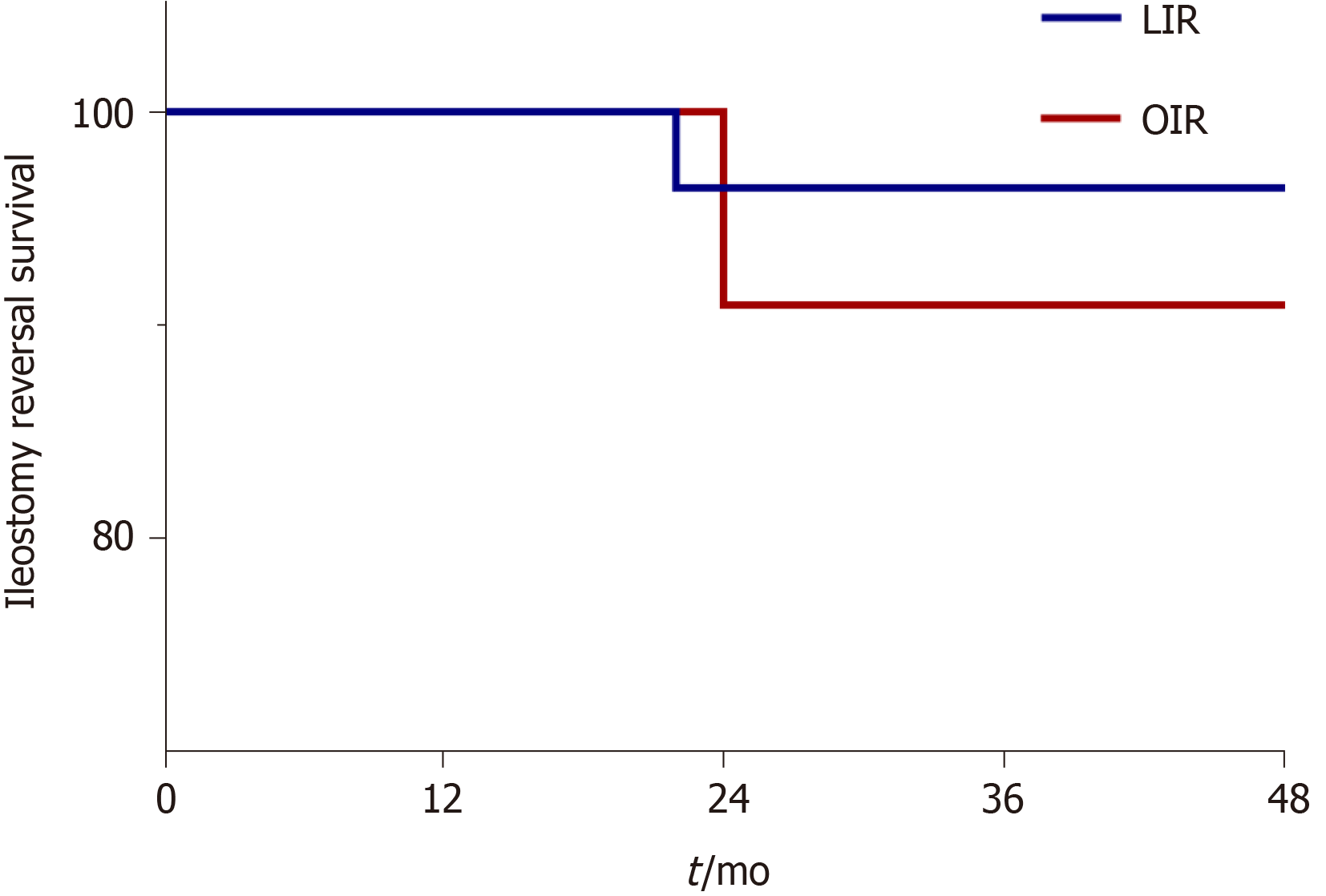

Postoperative recovery, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, and days to flatus and soft diet were similar between the two groups. Enterolysis was required for 42/48 (87.5%) patients in the LIR group and 5/12 (41.7%) in the OIR group (P < 0.05). However, when cases of enterectomy combined with IR were excluded, OIR was still advantageous for patients with CD. In those cases, OIR was superior to LIR in terms of days to flatus (1.7 ± 0.7 d vs 2.3 ± 0.6 d, respectively, P < 0.05), days to soft diet (2.7 ± 0.7 d vs 4.5 ± 1.7 d, respectively, P < 0.05), and hospitalization costs (37301 RMB vs 57967 RMB, respectively, P < 0.05) (Table 2). There was no significant difference in postoperative complications between the LIR and OIR groups (10.4% vs 16.7%, respectively). One patient in the LIR group developed an anastomotic fistula after surgery and recovered after continuous double-cannula irrigation, which explains why one patient in the LIR group was hospitalized for 32 d. Another patient developed anastomotic bleeding, which was resolved after hemostasis treatment. One patient with ileus recovered after conservative treatment. Two patients developed incisional infections in both the LIR and OIR groups and recovered after periodic dressing change. As a long-term outcome, the reoperation rate after IR was similar between the LIR and OIR groups. One patient in the LIR group and one in the OIR group underwent enterectomy again at 22 and 24 mo, respectively (Figure 2).

| Ileostomy reversal (without enterectomy) | Ileostomy reversal | |||||

| Variable | Laparoscopic (n = 30) | Open (n = 7) | P value | Laparoscopic (n = 48) | Open (n = 12) | P value |

| Operative time, min | 116.5 ± 38.4 | 117.1 ± 28.6 | NS | 128.2 ± 41.7 | 142.5 ± 41.7 | NS |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 69.7 ± 93.1 | 71.4 ± 94.8 | NS | 73.1 ± 91.3 | 94.2 ± 88.1 | NS |

| Days to flatus, d, mean ± SD | 2.3 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.7 | P < 0.05 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Days to soft diet, d, mean ± SD | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 2.7 ± 0.7 | P < 0.05 | 5.1 ± 3.9 | 3.8 ± 1.4 | NS |

| Total postoperative complication, n (%) | 3 (10) | 1 (14.3) | NS | 5 (10.4) | 2 (16.7) | NS |

| Anastomotic hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Ileus | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Wound infection | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Reoperation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Readmission after discharge | 0 | 0 | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| Length of stay, d, mean ± SD (range) | 9.6 ± 2.7 (5-15) | 8.6 ± 2.8 (6-15) | NS | 10.3 ± 4.0 (5-32) | 10.8 ± 3.7(6-18) | NS |

| Cost (RMB) | 57967 | 37301 | P < 0.05 | 62916 | 52274 | NS |

The aim of this retrospective study was to compare the feasibility, safety, and short-term and long-term outcomes of LIR vs OIR for CD. The results showed that LIR is a safe and feasible technique with acceptable outcomes and, thus, is worthy of further promotion and clinical study.

For high-risk intestinal anastomosis, the use of prophylactic ileostomy can signi

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the surgical approach and postoperative recovery of LIR for CD. In this study, cases of enterectomy during IR were excluded in order to compare OIR vs LIR alone. The results showed that postoperative recovery of patients with CD was better in the OIR group than the LIR group. This result is not difficult to explain. CD is a progressive disease resulting in fibrosis of the entire digestive tract. So, the entirety of the small intestine and colon can be explored during laparoscopic surgery, while only relatively small portions can be explored by open surgery. Also, in both LIR and OIR, incisions of the same length were made around the original ileostomy. Moreover, less minimally invasive instruments were used in OIR, so hospitalization costs were lower. In addition, laparoscopy is more convenient for the surgeon to dissociate the ileostoma from the abdominal cavity because of the good field of vision. Meanwhile, laparoscopy provides a clear field of vision of the entire gastrointestinal tract, which facilitates assessment of the remaining length of the healthy intestine, as well as the diseased portions. Therefore, laparoscopy greatly improves the rate of enterolysis and reduces the incidence of ileus. In this study, there was a significant difference in the rate of enterolysis between the IR and OIR groups (87.5% vs 41.7%, respectively, P < 0.05). In this regard, laparoscopy is undoubtedly beneficial to patients with CD. Hence, we continue to combine IR with enterectomy. The results of the present study showed that LIR did not increase the operative time, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative recovery time, length of hospitalization stay, hospitalization costs, or reoperation rate. Therefore, LIR is not a contraindication for patients with CD. In this study, 18 patients underwent enterectomy simultaneously with IR. In general, there are two main reasons for resection of the diseased intestinal segment at the same time of IR. First, ileostomy is often performed as an emergency surgery, as the diseased intestine can be removed at a later stage in the remission stage of CD. Second, during surgery for CD, excision of the intestine should be limited to avoid the occurrence of short bowel syndrome, as disease of the bowel can be alleviated with the use of biological agents. However, if drug treatment fails, simultaneous resection of the diseased bowel can be considered during IR.

Studies have shown that LIR with intracorporeal anastomosis was associated with shorter length of hospitalization without increasing overall costs[17]. A double-blind randomized controlled trial showed that intracorporeal anastomosis can reduce bowel manipulation and mesentery traction, which promotes quicker recovery of bowel function[27]. However, in the case of CD, extracorporeal anastomosis is preferred in our center because CD is often accompanied by thickening of the mesentery and vasculature, thus hemostasis and reinforcing sutures are often required after anastomosis. These procedures will be safer and more reliable in vitro. In order to avoid anastomotic stoma-associated strictures in patients with CD, in addition to side-to-side anastomosis in digestive tract reconstruction, extracorporeal anastomosis can ensure the maximum size of the anastomotic stoma. For extracorporeal anastomosis, the length of the incision was not increased, which alleviated postoperative pain and improved satisfaction with the cosmetic result (Figure 1D-G).

LIR for CD is both safe and feasible. The short-term and long-term outcomes of LIR are comparable to those of OIR and do not prolong postoperative recovery. In view of the fact that this is a retrospective study with a small sample size, larger prospective trials are required to further confirm these findings.

The advantages of minimally invasive surgery for ileostomy reversal (IR) have attracted increasing attention, although relatively few studies have investigated the benefits of IR for patients with Crohn's disease (CD).

It is worthwhile to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of laparoscopy for patients with CD.

To compare the safety, feasibility, and short-term and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic IR (LIR) vs open IR (OIR) for treatment of CD.

The baseline characteristics, operative data, and short-term (30-d) and long-term outcomes of patients with CD who underwent LIR and OIR between January 2017 and January 2020 were retrieved from an electronic database and retrospectively reviewed.

A total of 60 eligible patients were enrolled into the study, including 48 in the LIR group and 12 in the OIR group. There were no statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics, operative data, or short-term and long-term outcomes between the two groups. However, patients in the LIR group more frequently required lysis of adhesions as compared to those in the OIR group. Notably, following exclusion of patients who underwent enterectomy plus IR, OIR was more advantageous in terms of postoperative recovery of gastrointestinal function and hospitalization costs.

The safety and feasibility of LIR for the treatment of CD are comparable to those of OIR with no increase in intraoperative or postoperative complications.

LIR is feasible and safe for the treatment of CD patients with IR, and the short-term and long-term results are similar to those of OIR, thus further studies are warranted. In view of the fact that this is a retrospective study with a small sample size, larger prospective trials are required to further confirm these findings.

| 1. | Neary PM, Aiello AC, Stocchi L, Shawki S, Hull T, Steele SR, Delaney CP, Holubar SD. High-Risk Ileocolic Anastomoses for Crohn's Disease: When Is Diversion Indicated? J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Celentano V, O'Leary DP, Caiazzo A, Flashman KG, Sagias F, Conti J, Senapati A, Khan J. Longer small bowel segments are resected in emergency surgery for ileocaecal Crohn's disease with a higher ileostomy and complication rate. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bitner D, D'Andrea A, Grant R, Khetan P, Greenstein AJ. Ileostomy reversal after subtotal colectomy in Crohn's disease: a single institutional experience at a high-volume center. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:2361-2363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sun X, Han H, Qiu H, Wu B, Lin G, Niu B, Zhou J, Lu J, Xu L, Zhang G, Xiao Y. Comparison of safety of loop ileostomy and loop transverse colostomy for low-lying rectal cancer patients undergoing anterior resection: A retrospective, single institute, propensity score-matched study. J BUON. 2019;24:123-129. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mege D, Michelassi F. Laparoscopy in Crohn Disease: Learning Curve and Current Practice. Ann Surg. 2020;271:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Rogler G. Mechanisms, Management, and Treatment of Fibrosis in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:340-350.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 44.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM; MRC CLASICC trial group. Short-term endpoints of conventional vs laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2360] [Cited by in RCA: 2326] [Article Influence: 110.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Panteleimonitis S, Ahmed J, Parker T, Qureshi T, Parvaiz A. Laparoscopic resection for primary and recurrent Crohn's disease: A case series of over 100 consecutive cases. Int J Surg. 2017;47:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Royds J, O'Riordan JM, Mansour E, Eguare E, Neary P. Randomized clinical trial of the benefit of laparoscopy with closure of loop ileostomy. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1295-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mrak K, Uranitsch S, Pedross F, Heuberger A, Klingler A, Jagoditsch M, Weihs D, Eberl T, Tschmelitsch J. Diverting ileostomy vs no diversion after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: A prospective, randomized, multicenter trial. Surgery. 2016;159:1129-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cauley CE, Patel R, Bordeianou L. Use of Primary Anastomosis With Diverting Ileostomy in Patients With Acute Diverticulitis Requiring Urgent Operative Intervention. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61:586-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Salvadalena G. Incidence of complications of the stoma and peristomal skin among individuals with colostomy, ileostomy, and urostomy: a systematic review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2008;35:596-607; quiz 608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Bafford AC, Irani JL. Management and complications of stomas. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:145-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kaidar-Person O, Person B, Wexner SD. Complications of construction and closure of temporary loop ileostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;201:759-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ; COlorectal cancer Laparoscopic or Open Resection II (COLOR II) Study Group. Laparoscopic vs open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in RCA: 1249] [Article Influence: 96.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Hida K, Okamura R, Sakai Y, Konishi T, Akagi T, Yamaguchi T, Akiyoshi T, Fukuda M, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto M, Nishigori T, Kawada K, Hasegawa S, Morita S, Watanabe M; Japan Society of Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery. Open vs Laparoscopic Surgery for Advanced Low Rectal Cancer: A Large, Multicenter, Propensity Score Matched Cohort Study in Japan. Ann Surg. 2018;268:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sujatha-Bhaskar S, Whealon M, Inaba CS, Koh CY, Jafari MD, Mills S, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ, Carmichael JC. Laparoscopic loop ileostomy reversal with intracorporeal anastomosis is associated with shorter length of stay without increased direct cost. Surg Endosc. 2019;33:644-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Su H, Luo S, Xu Z, Zhao C, Bao M, Wang X, Zhou Z, Zhou H. Satisfactory short-term outcome of total laparoscopic loop ileostomy reversal in obese patients: a comparative study with open techniques. Updates Surg. 2021;73:561-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coffey JC, O'Leary DP, Kiernan MG, Faul P. The mesentery in Crohn's disease: friend or foe? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2016;32:267-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stevens TW, Haasnoot ML, D'Haens GR, Buskens CJ, de Groof EJ, Eshuis EJ, Gardenbroek TJ, Mol B, Stokkers PCF, Bemelman WA, Ponsioen CY; LIR!C study group. Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection vs infliximab for terminal ileitis in Crohn's disease: retrospective long-term follow-up of the LIR! Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:900-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Makni A, Chebbi F, Ksantini R, Fétirich F, Bedioui H, Jouini M, Kacem M, Ben Mami N, Filali A, Ben Safta Z. Laparoscopic-assisted vs conventional ileocolectomy for primary Crohn's disease: results of a comparative study. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:137-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Umanskiy K, Malhotra G, Chase A, Rubin MA, Hurst RD, Fichera A. Laparoscopic colectomy for Crohn's colitis. A large prospective comparative study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:658-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yellinek S, Krizzuk D, Gilshtein H, Djadou TM, de Sousa CAB, Qureshi S, Wexner SD. Early postoperative outcomes of diverting loop ileostomy closure surgery following laparoscopic vs open colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:2509-2514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pei KY, Davis KA, Zhang Y. Assessing trends in laparoscopic colostomy reversal and evaluating outcomes when compared to open procedures. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:695-701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Russek K, George JM, Zafar N, Cuevas-Estandia P, Franklin M. Laparoscopic loop ileostomy reversal: reducing morbidity while improving functional outcomes. JSLS. 2011;15:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Young MT, Hwang GS, Menon G, Feldmann TF, Jafari MD, Jafari F, Perez E, Pigazzi A. Laparoscopic Versus Open Loop Ileostomy Reversal: Is there an Advantage to a Minimally Invasive Approach? World J Surg. 2015;39:2805-2811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Allaix ME, Degiuli M, Bonino MA, Arezzo A, Mistrangelo M, Passera R, Morino M. Intracorporeal or Extracorporeal Ileocolic Anastomosis After Laparoscopic Right Colectomy: A Double-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:762-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Souza JLS S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH