Published online Jan 27, 2020. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v12.i1.17

Peer-review started: October 3, 2019

First decision: October 24, 2019

Revised: November 6, 2019

Accepted: November 28, 2019

Article in press: November 28, 2019

Published online: January 27, 2020

Processing time: 84 Days and 23.1 Hours

Loco-regional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) during the period awaiting liver transplantation (LT) appears to be a logical approach to reduce the risk of tumor progression and dropout in the waitlist. Living donor LT (LDLT) offers a flexible timing for transplantation providing timeframe for well preparation of transplantation.

To investigate outcomes in relation to the intention of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy in LDLT for HCC patients.

A total of 308 consecutive patients undergoing LDLTs for HCC between August 2004 and December 2018 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were grouped according to the intention of loco-regional therapy prior to LT, and outcomes of patients were analyzed and compared between groups.

Overall, 38 patients (12.3%) were detected with HCC recurrence during the follow-up period after LDLT. Patients who were radiologically beyond the University of California at San Francisco criteria and received loco-regional therapy as down-staging therapy had significant inferior outcomes to other groups for both recurrence-free survival (RFS, P < 0.0005) and overall survival (P = 0.046). Moreover, patients with defined profound tumor necrosis (TN) by loco-regional therapy had a superior RFS (5-year of 93.8%) as compared with others (P = 0.010).

LDLT features a flexible timely transplantation for patient with HCC. However, the loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT does not seem to provide benefit unless a certain effect in terms of profound TN is noted.

Core tip: Liver transplantation (LT) has become an ideal treatment for liver cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as it simultaneously removes the tumors and cures the underlying liver cirrhosis. Living donor LT (LDLT) offers a flexible timing for transplantation providing timeframe for well preparation of transplantation. The study investigates the outcome in relation to the intention of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy in LDLT for HCC. Although the study is still unable to establish a definitive therapeutic protocol to achieve a beneficial outcome of HCC after LDLT, achieving profound tumor necrosis by loco-regional therapy could also offer better outcomes for patients undergoing LDLT for HCC.

- Citation: Wu TH, Wang YC, Cheng CH, Lee CF, Wu TJ, Chou HS, Chan KM, Lee WC. Outcomes associated with the intention of loco-regional therapy prior to living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020; 12(1): 17-27

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v12/i1/17.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v12.i1.17

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a major cause for cancer-related death worldwide, and its management is rapidly evolving during the last decade[1]. However, the selection of appropriate treatment for patients with HCC remains a challenge because of the clinical complexity of patients and the variability of treatment efficacy. As such, the concept of HCC treatment has currently embraced a multidisciplinary approach, which remarkably improved the long-term patients’ outcome.

Surgical treatments including liver resection (LR) and liver transplantation (LT), currently provide the greatest opportunity for the potential cure of HCC. Moreover, LT is regarded as the best choice for patients who have liver cirrhosis associated with HCC but ineligible for primary LR, as the transplantation cures the underlying cirrhosis and provides the lowest cancer recurrence rate. Although the Milan Criteria set a gold standard for LT to treat HCC with favorable overall and recurrence-free survival (RFS), the strict criteria also limits the range of patients who can receive LT[2]. Therefore, numerous alternative expanded criteria have been introduced, showing comparable clinical outcomes than the Milan criteria[3-7].

However, the expansion of selection criteria should be taken cautiously, because HCC recurrence remains a great concern, leading to a poor outcome after LT. By contrast, loco-regional therapy prior to LT might be considered for the purpose of down-staging the tumor, to reduce the risk of progression and dropout of patients on the waiting list, or to improve the possibility of a favorable outcome after LT[8-11]. Previous studies had shown that loco-regional therapy is effective to improve the outcome after LT, but these results seems to be biased by the robust pathological response to the treatment in certain patients[12-16]. Nonetheless, a consensus has not been reached for the timing and the modality of treatment. Additionally, living donor LT (LDLT) account for the majority of LT events, due to the scarcity of organ from deceased donors in most of the Asian countries. Therefore, further investigation of LDLT remains important to optimize therapeutic strategies for patients with HCC. This study enrolled patients who had undergone LDLT for HCC, and further investigated the impact of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy after LT. Apart from that, loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT based on the intention of treatment were also examined.

All patients who had undergone LDLT for HCC at the Organ Transplantation Institute of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, Taiwan, were retrospectively analysed after the approval of the Institutional Review Board (99-3089B). As a result, a total of 308 consecutive patients undergone LDLTs for HCC between August 2004 and December 2018 at the transplantation center were included in this study, in which all patients were pathologically proven of HCC through histological examination of the explant liver. Subsequently, patients were grouped according to the intention of loco-regional therapy prior to LT, and outcomes of patients were analyzed and compared between groups.

The diagnosis of HCC was based on the European Association for the Study of the Liver and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines[17,18]. The treatment of HCC is mainly based on the algorithm of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system. In line with the current practices for HCC, the treatment modality options were multidisciplinary and depended on patient’s performance, cirrhotic status of the liver, and the tumor characteristics[1]. In particular, LR is always considered the preferred treatment for HCC. Patients with HCC ineligible to LR and willing to undergo transplantation were evaluated for LT eligibility. The transplantation criteria for HCC were based on the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) criteria, that use radiological imaging evidence in terms of tumor number and size[7].

Based on the clinical context, we divided patients with HCC waiting to receive LT in three groups. Group I comprised patients who had not received any loco-regional therapy for HCC before LDLT. Group II comprised patients who had unresectable HCC and met the UCSF radiological criteria (rUCSF), but were unable to receive LT immediately due to the availability of donors or hesitation about LT surgery. These patients would thus be recommended for loco-regional therapy in order to reduce the risk of tumor progression. Group III comprised patients who had an HCC beyond rUCSF criteria, and loco-regional therapy was performed for the purpose of down-staging.

All LDLT procedures were performed using standard techniques and without venous bypass. The immunosuppressant regimen consisted of calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites, and steroid as previous described[13]. After transplantation, the explanted livers were subjected to a thorough histological examination to determine the HCC pathological characteristics. Patients who had received loco-regional therapy were further pathologically examined for effectiveness in relation to the degree of tumor necrosis (TN) as previous described[13], and a mean TN higher than 60% was defined as profound TN. Additionally, all patients were re-assessed for HCC in terms of tumor number and size for the transplantation criteria based on pathological results that termed as pathologic UCSF (pUCSF).

After LDLT, patients were regularly followed-up for graft function and tumor recurrence in the department. Generally, liver ultrasonography was performed in a minimum of 3-mo intervals. Radiological imaging including computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging was routinely performed at 1, 3, 6, and 12 mo of the first year and annually afterward or whenever there was suspicion of HCC recurrence.

The outcome assessments included HCC RFS and the patients overall survival (OS). RFS was measured from the date of LDLT to the detection of HCC recurrence, while OS was calculated from the date of LDLT to the death of patient or until the end of this study. The survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The categorical clinic-pathological variables were analyzed using the χ2 or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables are presented as median and range followed by comparison using the Kruskal–Wallis test. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software package version 25.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) for Windows. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician.

Among 738 LDLTs, 308 patients (41.7%) including 249 males and 59 females were confirmed to have HCC and were included in this study. Based on the aforementioned grouping criteria, 52 patients (16.9%) were in Group I, 228 patients (74.0%) were in Group II, and the remaining 28 patients (9.1%) were in Group III. During the follow-up, 38 patients (12.3%) were detected with HCC recurrence in a period from 1.2 to 92.5 mo after LT (median, 15.0 mo). Overall, 103 patients (33.4%) died during the study, of which 17 were hospital mortalities (5.5%) within 3 mo, and 30 patients (9.7%) died of HCC recurrence after LDLT. The remaining 205 alive patients included 6 patients with recurrent HCC and 199 HCC-free patients at the end of this study.

The clinical features of the patient groups are summarized in Table 1. Generally, the majority of clinical features were similar between groups. As group III represented HCC beyond rUCSF criteria for transplantation, their tumor characteristics in terms of number and size were significantly more aggressive than the other two groups. However, the severity of liver cirrhosis and the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score was significantly higher in group I. Specifically, 21.2% and 24.6% of patients in group I and group II, respectively, were beyond pUCSF criteria, which did not correlate with radiological criteria before LDLT. Similarly, after pathological examination, 21.4% of patients within group III were within UCSF criteria.

| Group I (n = 52) | Group II (n = 228) | Group III (n = 28) | P value | |

| Age, median (range) | 58 (13-70) | 56 (33-69) | 56 (38-69) | 0.246 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 39 (75.0) | 186 (81.6) | 24 (85.7) | 0.437 |

| Female | 13 (25.0) | 42 (18.4) | 4 (14.3) | |

| Hepatitis status, n (%) | ||||

| Hepatitis B positive | 25 (48.1) | 152 (66.7) | 19 (67.9) | 0.181 |

| Hepatitis C positive | 17 (32.7) | 51 (22.4) | 7 (25.0) | |

| HBV + HCV | 6 (11.5) | 10 (4.4) | 1 (3.6) | |

| None | 4 (7.7) | 15 (6.6) | 1 (3.6) | |

| MELD score, median (range) | 15.5 (8-36) | 10.0 (6-35) | 9.5 (5-22) | < 0.0001 |

| Child Class, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| A | 9 (17.3) | 116 (50.9) | 16 (57.1) | |

| B | 17 (32.7) | 81 (35.5) | 8 (28.6) | |

| C | 26 (50.0) | 31 (13.6) | 4 (14.3) | |

| AFP, median (range) | 9.2 (2.0-1552) | 11.8 (1.3-18250) | 53.4 (2.0-461) | 0.098 |

| Graft type, n (%) | 0.578 | |||

| Left liver | 2 (3.8) | 16 (7.0) | 1 (3.6) | |

| Right liver | 50 (96.2) | 212 (93.0) | 27 (96.4) | |

| GRWR (%), n (%) | 0.037 | |||

| ≤ 0.8 | 7 (13.5) | 64 (28.1) | 4 (14.3) | |

| > 0.8 | 45 (86.5) | 164 (71.9) | 24 (85.7) | |

| Tumor Number, median (range) | 1 (1-20) | 2 (1-22) | 4 (1-20) | < 0.0001 |

| Maximum tumor size, median (range) | 2.1 (1.0-7.5) | 2.5 (1.0-9.2) | 3.4 (1.5-11.2) | 0.006 |

| Pathologic UCSF, n (%) | < 0.0001 | |||

| Within | 41 (78.8) | 172 (75.4) | 6 (21.4) | |

| Beyond | 11 (21.2) | 56 (24.6) | 22 (78.6) | |

| Histology grade, n (%) | 0.382 | |||

| 1-2 | 43 (82.7) | 169 (74.1) | 20 (71.4) | |

| 3-4 | 9 (17.3) | 59 (25.9) | 8 (28.6) | |

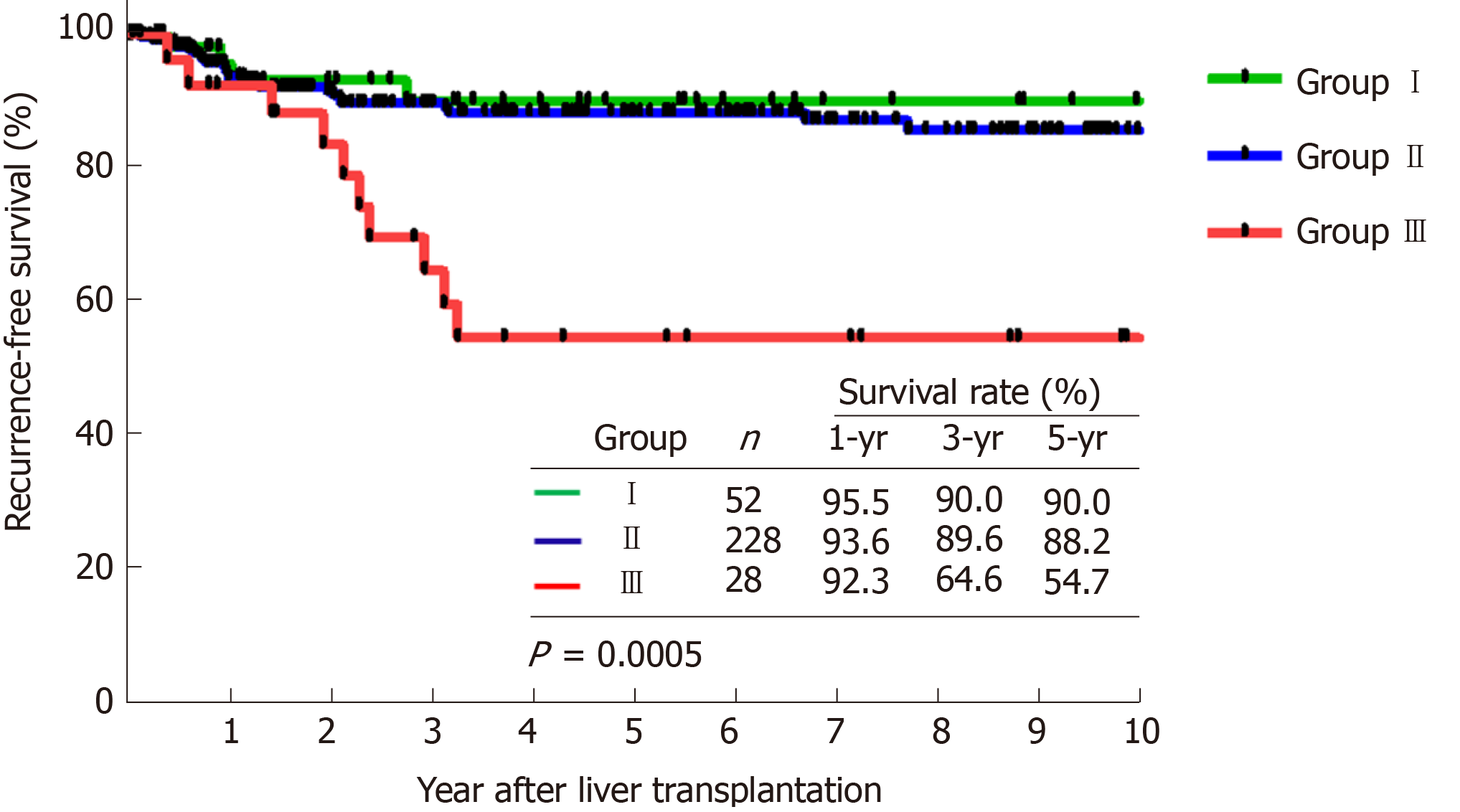

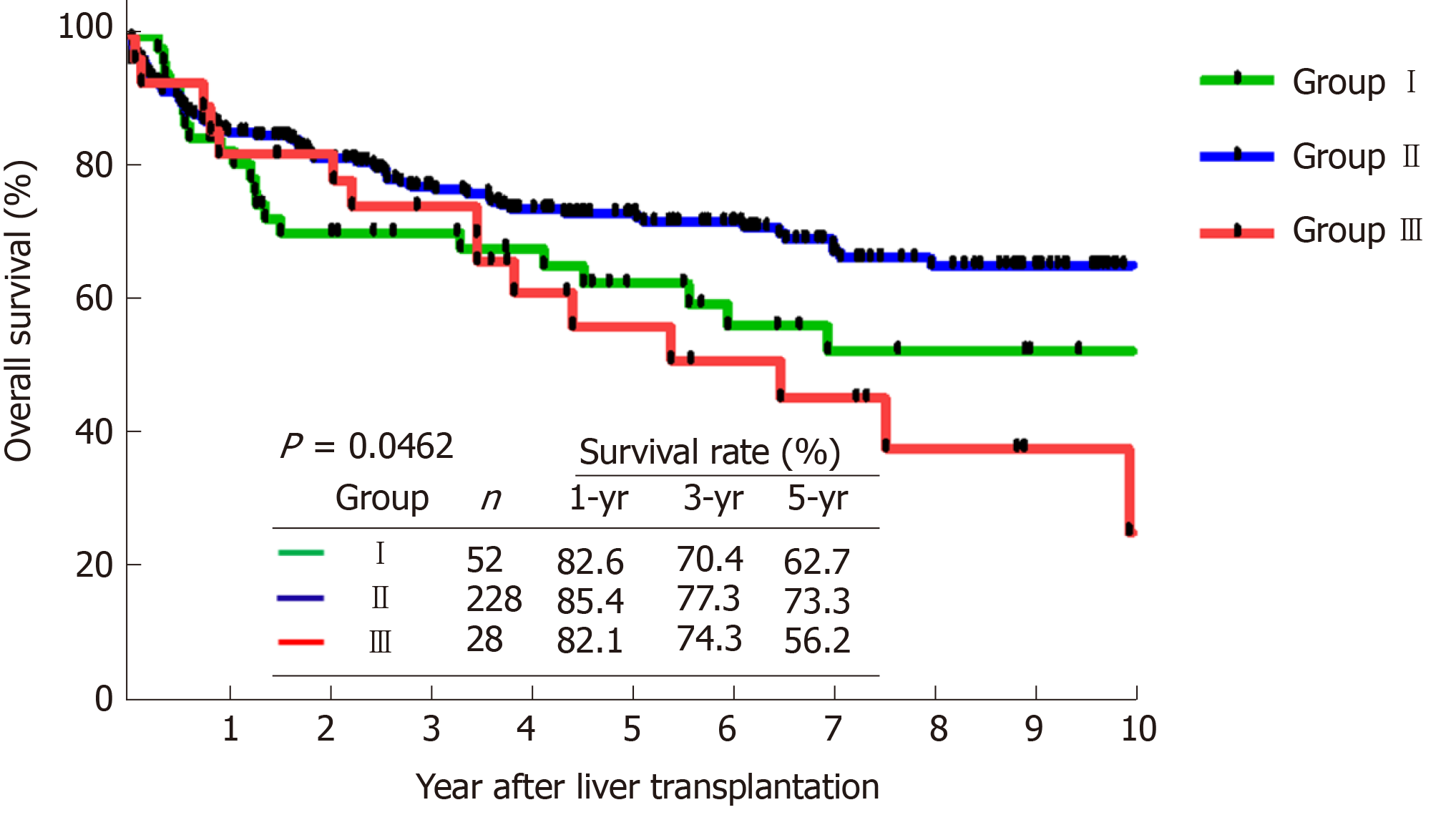

The comparison of survival curves showed that both RFS (Figure 1, P < 0.0005) and OS (Figure 2, P = 0.046) were significantly different between the 3 groups. Moreover, the subgroup analysis showed that group III had significant poorer outcomes (5-years RFS and OS of 54.7% and 56.2%, respectively) compared with group I (90.0%, and 62.7%) and group II (88.2%, and 73.3%), However, RFS and OS outcomes between group I and II were statistically similar.

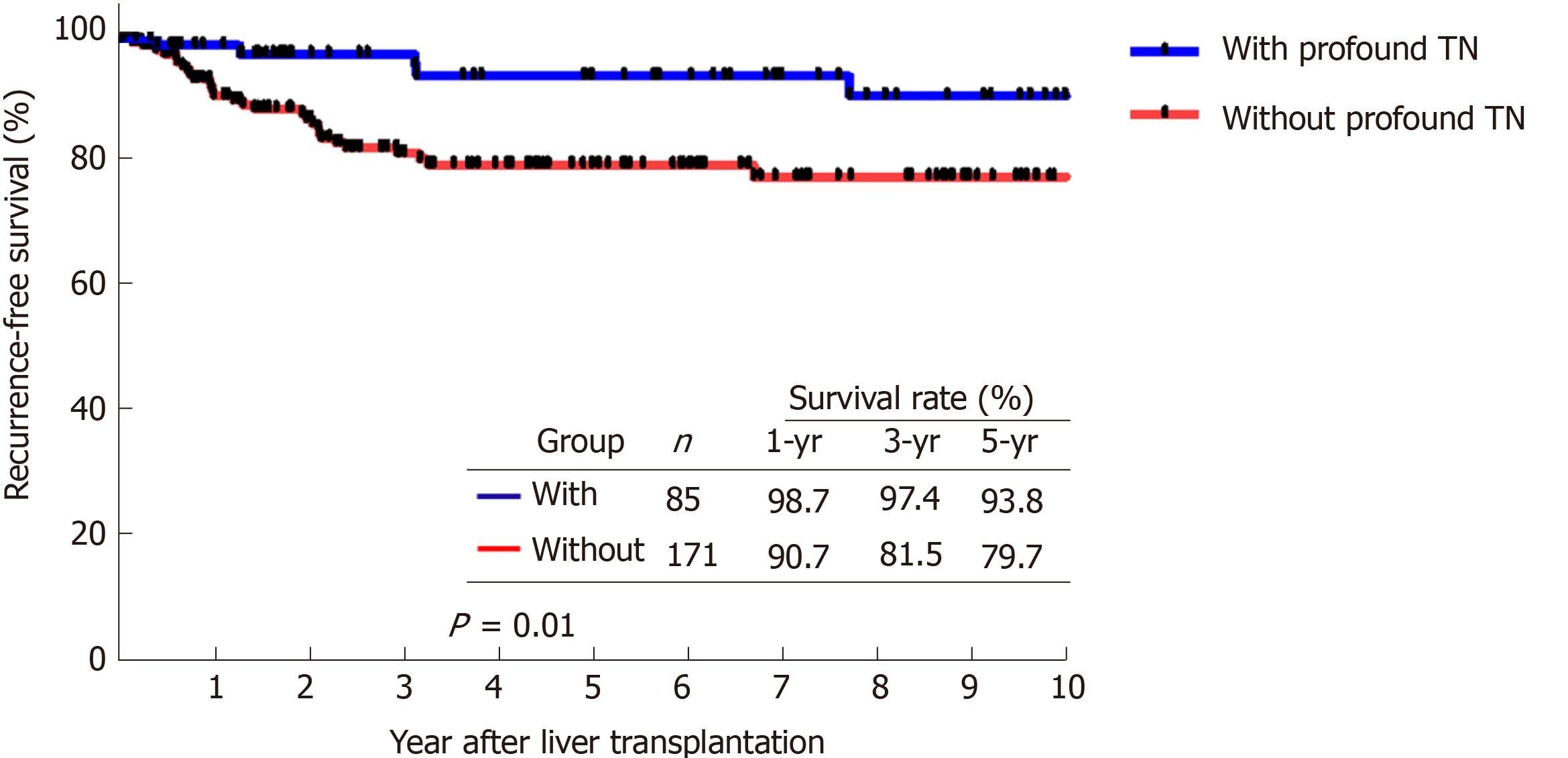

Subsequently, patients who had received loco-regional therapy were further pathologically examined for effectiveness in relation to the degree of TN. Patients with loco-regional therapy were further compared based on the definition of profound TN. A total of 85 patients undergoing loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT, accounting for 33.2% of all patients, had profound TN.

The clinico-pathological features of patients regarding the TN status were compared in Table 2. The serum level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) was significantly higher in patients who were unable to get profound TN, as well as the size and number of the HCC features. However, loco-regional therapy related to the treatment timing and modality were both not significantly difference between the two patient groups. Among patients with a profound TN, we observed a higher percentage of patients who were within the radiological and pathological UCSF criteria.

| Profound tumor necrosis (≥ 60%) | |||

| With (n = 85) | Without (n = 171) | P value | |

| Age, median (range) | 55 (33-67) | 56 (33-69) | 0.177 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.198 | ||

| Male | 66 (77.6) | 144 (84.2) | |

| Female | 19 (22.4) | 27 (15.8) | |

| Hepatitis status, n (%) | 0.834 | ||

| Hepatitis B positive | 54 (63.5) | 117 (68.4) | |

| Hepatitis C positive | 22 (25.9) | 36 (21.1) | |

| HBV + HCV | 4 (4.7) | 7 (4.1) | |

| None | 5 (5.9) | 11 (6.4) | |

| MELD score, median (range) | 11 (6-27) | 10 (5-35) | 0236 |

| Child Class, n (%) | 0.460 | ||

| A | 46 (47.1) | 92 (53.8) | |

| B | 34 (40.0) | 55 (32.2) | |

| C | 11 (12.9) | 24 (14.0) | |

| AFP, median (range) | 9.0 (1.7-1300) | 14.9 (1.3-18250) | 0.018 |

| Tumor Number, median (range) | 1 (1-7) | 3 (1-22) | < 0.0001 |

| Maximum tumor size, median (range) | 2.0 (0.7-7.0) | 2.6 (0.5-11.2) | 0.011 |

| Loco-regional therapy, n (%) | 0.756 | ||

| Within 3 mo | 45 (52.9) | 87 (50.9) | |

| Beyond 3 mo | 40 (47.1) | 84 (49.1) | |

| Loco-regional therapy modality, n (%) | 0.145 | ||

| Local ablation | 12 (14.1) | 16 (9.4) | |

| TACE | 63 (74.1) | 144 (84.2) | |

| TACE + ablation | 10 (11.8) | 11 (6.4) | |

| Number of loco-regional therapy | 1 (1-17) | 1 (1-16) | 0.084 |

| Radiologic UCSF, n (%) | 0.007 | ||

| Within | 82 (96.5) | 146 (85.4) | |

| Beyond | 3 (3.5) | 25 (14.6) | |

| Pathologic UCSF, n (%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Within | 75 (88.2) | 103 (60.2) | |

| Beyond | 10 (11.8) | 68 (39.8) | |

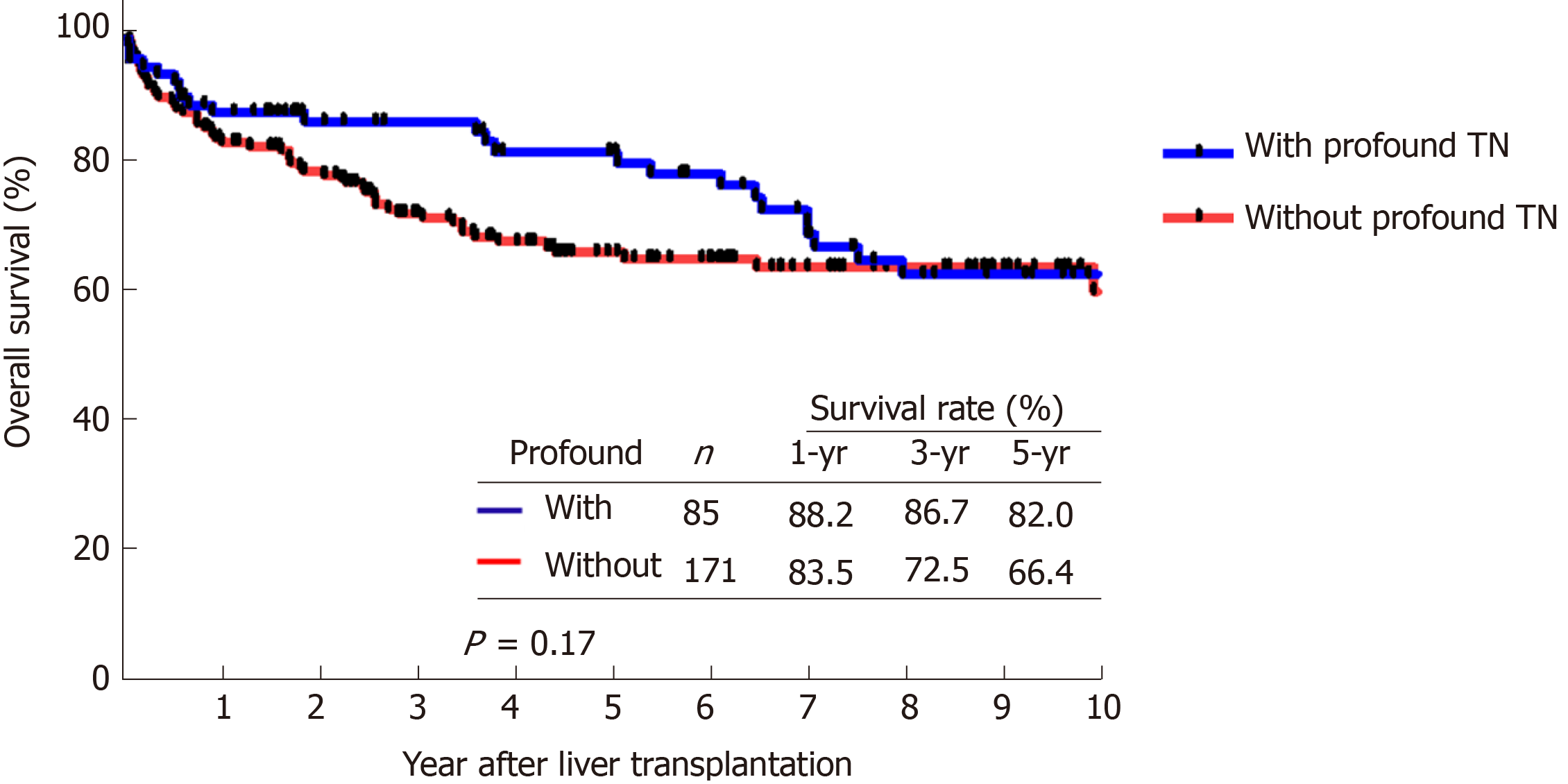

We compared the RFS and OS curves of patients who had profound TN and patients who did not. The RFS of patients with profound TN at 1, 3, and 5 years were 98.7%, 97.4%, and 93.8%, respectively, whereas the RFS of patients without profound TN at the same time points were 90.7%, 81.5%, and 79.7% (Figure 3, P = 0.01). Moreover, the comparison of OS curves between these two groups were also not significant. The cumulative OS of patients with profound TN at 1, 3, and 5 years were 88.2%, 86.7%, and 82.0%, respectively, while the OS of patients without profound TN were 83.5%, 72.5%, and 66.4%, respectively (Figure 4, P = 0.17).

Since the first successful LT performed by Thomas E Starzl half a century ago, LT has become a common and routine operation in many transplantation centers worldwide. Moreover, a flourishing LDLT practice has evolved in East Asia due to the scarcity of deceased donors[19]. Currently, LT has become the ideal curative treatment for liver cirrhosis associated with HCC, it simultaneously removes the tumors and cures the underlying liver cirrhosis. As such, LDLT offers a flexible timely transplantation possibility, providing a defining timeframe prepare the recipient before the operation. Theoretically, performing a pre-operative treatment might ameliorate the aggressiveness of HCC and improve the overall patient’s outcome. Therefore, the present study analyzed patients who underwent LDLT for HCC to investigate the outcome in relation to the pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy. According to this study, the outcome of LDLT for patient with HCC was satisfactory, with a favorable RFS rate. However, loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT seems to not provide beneficial outcome unless a certain effect of loco-regional therapy before LT is achieved.

Although the treatment algorithm based on BCLC staging is very clear, the optimal treatment modality selection for patient with unresectable HCC remains uncertain. Moreover, individual patient may have their own choice of treatment after general consideration. Information about therapeutic options, importance of benefits and harms, the uncertainties of available options, and a patient’s values through the implementation of shared decision making process could also affect the therapeutic decision[20]. Clinically, a care provider should inform patients of all risks involved with a certain treatment instead of forcing a treatment for patient. Therefore, patients with unresectable HCC would be evaluated for LT only if the patient was willing to undergo transplantation in the institute. Additionally, the scarcity of donor remains the major concern for LT. Thus, the majority of patients received loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT due to the lack of available donor for immediate transplantation. Apart from that, patients might be initially listed for a deceased donor liver transplant and turned to LDLT because of the long-time waiting and the fear of tumor progression. In those patients, loco-regional therapy was mostly performed in order to reduce the risk of tumor progression.

Generally, the living donor liver graft is a dedicated gift from a recipient’s relative, not competing with other patients awaiting for LT. LDLT usually offers a flexible timing for transplantation depending on the clinical scenario, the disease severity, and the preparation of available donor. In particular, the majority of patients with HCC have a low MELD score, meaning a non-life-threatening physical condition without a LT in a few weeks. The timeframe between the initiation of donor survey and matchup to LDLT in the institute is no longer than 4 wk. Therefore, a planned loco-regional therapy with such a short-term treatment seems unnecessary nor giving beneficial effects.

In line with the previous studies, profound TN was observed in those patients who had less aggressive HCC, lower AFP, a lower tumor number, and smaller tumor size[13,14,21]. Generally, the aim of both transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and local ablation is intend to induce TN as well as eradication of cancer cells. Although each modality has different therapeutic effects in terms of TN, sequential treatment or a combination of multi-modalities can lead to marked or complete necrosis for a HCC of defined size[22,23]. As such, the viable tumor burden could also be diminished by loco-regional therapy that results in TN and downstage of HCC status at a certain degree. Besides, a long waiting period might lead to tumor progression and patient ineligible for LT. Therefore, loco-regional therapy could also prevent dropout because of tumor progression among patients awaiting transplantation. However, timing and frequency of loco-regional therapy to achieve a profound TN response remain uncertain in the current clinical setting.

Additionally, it is difficult to assess TN through radiological imaging scan, and it could only be confirmed with thoroughly examination of the explanted liver after LT. Hence, it is unpractical to adjust the treatment strategy for LDLT on the basis of loco-regional therapy efficacy in terms of TN. Apart from that, radiological imaging scan could be mis-staging HCC. In this study, radiological images of nearly 20% of all the patients did not correlate to pathological staging. Moreover, interpret the radiological image of a cirrhotic liver is more difficult after loco-regional therapy. Nonetheless, loco-regional therapy for patient awaiting LT remains an international consensus for the management of HCC patients during the waiting time[8,24]. Hence, loco-regional therapy prior to LT might be insufficient for achieving a better outcome, but still encouraged as long as the patient is suitable for such treatment.

However, the outcomes related to the use of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy were not statistically different in this study. Currently, the UCSF criteria are widely accepted to justify LT for HCC, in which the low incidence of HCC recurrence might be unable to reflect significance difference in this study. Additionally, the majority of group II patients only received one round of loco-regional therapy, and thus therapeutic effect in terms of profound or complete TN seems unachievable. Generally, loco-regional therapy before LT is mostly performed to prevent tumor progression in a long waiting time period. Therefore, the increased number of loco-regional therapy could either reflect a long waiting time or a further tumor progression. However, a randomized controlled trial in terms of loco-regional therapy before LT may not be practical, in which the increased risk of tumor progression in certain study group might be a concern. Therefore, we are still unable to establish a definitive therapeutic protocol to achieve a beneficial outcome of HCC patients after LDLT.

In conclusions, although this study is limited by using a retrospective cohort, but few remarkable information might be helpful in planning therapeutic strategy for patients with HCC awaiting LDLT. A recent study showed that the use of loco-regional therapy could improve outcomes only in patients with a complete pathological response[14]. However, this study showed that achieving profound TN by loco-regional therapy could also offer better outcomes for patients undergoing LDLT for HCC. Therefore, loco-regional therapy for HCC prior to LDLT might be insufficient for achieving a better outcome but still encouraged as long as the patient is suitable for such treatment.

Liver transplantation (LT) has become an ideal curative treatment for liver cirrhosis associated with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as it simultaneously removes the tumors and cures the underlying liver cirrhosis. Although the overall outcome of LT for HCC is favorable, tumor recurrence is still a great concern. Hence, there remain several unmet needs for improving the long-term outcome of LT for HCC.

Living donor LT (LDLT) account for the majority of LT in most of Asian region because of the scarcity of organ from deceased donors. LDLT offers a flexible timing for transplantation providing timeframe for well preparation of transplantation. Theoretically, a pre-operative treatment might mitigate the tumor burden and improve the overall outcome of HCC patients. Therefore, further investigation of LDLT in terms of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy remains important to optimize therapeutic strategies for patients with HCC.

The main objectives of this study were to analyze patients who underwent LDLT for HCC to investigate the outcome in relation to the intention of pre-transplantation loco-regional therapy.

All patients who had undergone LDLT for HCC between August 2004 and December 2018 were retrospectively analyzed. Subsequently, patients were grouped according to the intention of loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT, and outcomes of patients were analyzed and compared between groups. Group I comprised patients who had not received any loco-regional therapy before LDLT. Group II comprised patients who had HCC within the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) radiological criteria (rUCSF), but had loco-regional before LDLT. Group III comprised patients who had an HCC beyond rUCSF criteria, and loco-regional therapy was performed for the purpose of down-staging.

Of 308 patients who underwent LDLT for HCC during the study period were divided into Group I (n = 52), Group II (n = 228) and Group III (n = 28) based on aforementioned definition. Overall, 38 patients (12.3%) were detected with HCC recurrence during the follow-up period after LDLT. Group III patients had significant inferior outcomes to other two groups for both recurrence-free survival (RFS, P < 0.0005) and overall survival (OS, P = 0.046). However, RFS and OS outcomes between group I and II were statistically similar. Moreover, patients with defined profound tumor necrosis by loco-regional therapy had a superior RFS as compared with others.

The outcome of LDLT for patient with HCC was satisfactory with a favorable RFS rate in this study. Nonetheless, loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT seems to not provide beneficial outcome unless a certain effect of loco-regional therapy prior to transplantation is achieved. Loco-regional therapy prior to LDLT might be insufficient for achieving a better outcome but still encouraged as long as the patient is suitable for such treatment.

The study is still unable to establish a definitive therapeutic protocol to achieve a beneficial outcome of HCC patients after LDLT. Nonetheless, loco-regional therapy for HCC patient awaiting LT remains an international consensus for the management of HCC patients during the waiting time. The low incidence of HCC recurrence might be unable to reflect significance difference in this study. Therefore, additional loco-regional therapy studies in terms of high quality or larger prospective cohort studies could be undertaken in HCC patients listed for LDLT.

The authors would like to thank Ms. Shu-Fang Huang from Department of General Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou for the statistical support and review.

| 1. | Dhir M, Melin AA, Douaiher J, Lin C, Zhen WK, Hussain SM, Geschwind JF, Doyle MB, Abou-Alfa GK, Are C. A Review and Update of Treatment Options and Controversies in the Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1112-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, Andreola S, Pulvirenti A, Bozzetti F, Montalto F, Ammatuna M, Morabito A, Gennari L. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5110] [Cited by in RCA: 5400] [Article Influence: 180.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 3. | DuBay D, Sandroussi C, Sandhu L, Cleary S, Guba M, Cattral MS, McGilvray I, Ghanekar A, Selzner M, Greig PD, Grant DR. Liver transplantation for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma using poor tumor differentiation on biopsy as an exclusion criterion. Ann Surg. 2011;253:166-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lee S, Ahn C, Ha T, Moon D, Choi K, Song G, Chung D, Park G, Yu Y, Choi N, Kim K, Kim K, Hwang S. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Korean experience. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010;17:539-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, Bhoori S, Schiavo M, Mariani L, Camerini T, Roayaie S, Schwartz ME, Grazi GL, Adam R, Neuhaus P, Salizzoni M, Bruix J, Forner A, De Carlis L, Cillo U, Burroughs AK, Troisi R, Rossi M, Gerunda GE, Lerut J, Belghiti J, Boin I, Gugenheim J, Rochling F, Van Hoek B, Majno P; Metroticket Investigator Study Group. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:35-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1623] [Article Influence: 90.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Sugawara Y, Tamura S, Makuuchi M. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Tokyo University series. Dig Dis. 2007;25:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, Watson JJ, Bacchetti P, Venook A, Ascher NL, Roberts JP. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33:1394-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1594] [Cited by in RCA: 1721] [Article Influence: 68.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Clavien PA, Lesurtel M, Bossuyt PM, Gores GJ, Langer B, Perrier A; OLT for HCC Consensus Group. Recommendations for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an international consensus conference report. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e11-e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 798] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Lesurtel M, Müllhaupt B, Pestalozzi BC, Pfammatter T, Clavien PA. Transarterial chemoembolization as a bridge to liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2644-2650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lu DS, Yu NC, Raman SS, Lassman C, Tong MJ, Britten C, Durazo F, Saab S, Han S, Finn R, Hiatt JR, Busuttil RW. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma as a bridge to liver transplantation. Hepatology. 2005;41:1130-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cucchetti A, Cescon M, Bigonzi E, Piscaglia F, Golfieri R, Ercolani G, Cristina Morelli M, Ravaioli M, Daniele Pinna A. Priority of candidates with hepatocellular carcinoma awaiting liver transplantation can be reduced after successful bridge therapy. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:1344-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Millonig G, Graziadei IW, Freund MC, Jaschke W, Stadlmann S, Ladurner R, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Response to preoperative chemoembolization correlates with outcome after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:272-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chan KM, Yu MC, Chou HS, Wu TJ, Lee CF, Lee WC. Significance of tumor necrosis for outcome of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma receiving locoregional therapy prior to liver transplantation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2638-2646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Agopian VG, Harlander-Locke MP, Ruiz RM, Klintmalm GB, Senguttuvan S, Florman SS, Haydel B, Hoteit M, Levine MH, Lee DD, Taner CB, Verna EC, Halazun KJ, Abdelmessih R, Tevar AD, Humar A, Aucejo F, Chapman WC, Vachharajani N, Nguyen MH, Melcher ML, Nydam TL, Mobley C, Ghobrial RM, Amundsen B, Markmann JF, Langnas AN, Carney CA, Berumen J, Hemming AW, Sudan DL, Hong JC, Kim J, Zimmerman MA, Rana A, Kueht ML, Jones CM, Fishbein TM, Busuttil RW. Impact of Pretransplant Bridging Locoregional Therapy for Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma Within Milan Criteria Undergoing Liver Transplantation: Analysis of 3601 Patients From the US Multicenter HCC Transplant Consortium. Ann Surg. 2017;266:525-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Na GH, Kim EY, Hong TH, You YK, Kim DG. Effects of loco regional treatments before living donor liver transplantation on overall survival and recurrence-free survival in South Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:98-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Halazun KJ, Tabrizian P, Najjar M, Florman S, Schwartz M, Michelassi F, Samstein B, Brown RS, Emond JC, Busuttil RW, Agopian VG. Is it Time to Abandon the Milan Criteria?: Results of a Bicoastal US Collaboration to Redefine Hepatocellular Carcinoma Liver Transplantation Selection Policies. Ann Surg. 2018;268:690-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6633] [Article Influence: 442.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4059] [Cited by in RCA: 4564] [Article Influence: 326.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 19. | Chen CL, Kabiling CS, Concejero AM. Why does living donor liver transplantation flourish in Asia? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:746-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Op den Dries S, Annema C, Berg AP, Ranchor AV, Porte RJ. Shared decision making in transplantation: how patients see their role in the decision process of accepting a donor liver. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1072-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Merani S, Majno P, Kneteman NM, Berney T, Morel P, Mentha G, Toso C. The impact of waiting list alpha-fetoprotein changes on the outcome of liver transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2011;55:814-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Wong LL, Tanaka K, Lau L, Komura S. Pre-transplant treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: assessment of tumor necrosis in explanted livers. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zalinski S, Scatton O, Randone B, Vignaux O, Dousset B. Complete hepatocellular carcinoma necrosis following sequential porto-arterial embolization. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6869-6872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kim SH, Lee EC, Park SJ. Pretransplant locoregional therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: encouraging but insufficient. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2018;7:136-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Taiwan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chen Z, Guo JS, Niu ZS S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ