Published online Sep 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i9.358

Peer-review started: May 9, 2019

First decision: June 12, 2019

Revised: July 8, 2019

Accepted: August 7, 2019

Article in press: August 7, 2019

Published online: September 27, 2019

Processing time: 153 Days and 16.2 Hours

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a disease surrounded by misunderstanding and controversies. Knowledge about the etymology of pseudomyxoma is useful to remove the ambiguity around that term. The word pseudomyxoma derives from pseudomucin, a type of mucin. PMP was first described in a case of a woman alleged to have a ruptured pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary, a term that has disappeared from today’s classifications of cystic ovarian neoplasms. It is known today that in the majority of cases, the origin for PMP is an appendiceal neoplasm, often of low histological grade. Currently, ovarian tumors are wrongly being considered a significant recognized etiology of PMP. PMP classification continues to be under discussion, and experts’ panels strive for consensus. Malignancy is also under discussion, and it is shown in this review that there is a long-standing historical reason for that. Surgery is the main tool in the treatment armamentarium for PMP, and the only therapy with potential curative option.

Core tip: Pseudomyxoma peritonei is an orphan disease that explains the misunderstanding around this nosologic entity. There is still controversy over its definition and classification. Cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary has been repeatedly and wrongly stated as an important etiology of pseudomyxoma. The aim of the present review is to provide clarifications on misconceptions surrounding PMP and to explain the historical sources from which such misconceptions have been drawn.

- Citation: Morera-Ocon FJ, Navarro-Campoy C. History of pseudomyxoma peritonei from its origin to the first decades of the twenty-first century. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(9): 358-364

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i9/358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i9.358

The National Library of Medicine terminology defines pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) as “A condition characterized by poorly-circumscribed gelatinous masses filled with malignant mucin-secreting cells”. This paragraph is exact. The definition is completed with descriptions of the etiologies: “Forty-five percent of pseudomyxomas arise from the ovary, usually in a mucinous cystadenocarcinoma (cystadenocarcinoma, mucinous), which has prognostic significance. PMP must be differentiated from mucinous spillage into the peritoneum by a benign mucocele of the appendix (Segen, Dictionary of Modern Medicine, 1992)”.

Those statements are erroneous. It has been demonstrated that PMP arises from appendiceal neoplasms, and rarely from other tumors such as neoplasms from the colon, urachus, or pancreas. Mucocele is a very ambiguous term. Consequently, this definition needs to be amended. Today, the etiology and epidemiology of PMP have been elucidated, though some ambiguity remains. The Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (commonly known as PSOGI) endeavored to clarify concepts and published a consensus for classification of PMP and associated appendiceal neoplasia in 2016[1].

This manuscript deals with the history of this rare disease, from the origin of the terminology to the current notions.

Myxoma is a benign tumor of connective tissue containing mucous material (the most common primary tumor of the heart). The term pseudomyxoma in PMP does not come from the histology of myxoma but comes from pseudomucin. The prefix myxo-, Latin form for muxa from the Greek, and meaning mucus, used to be employed when mucus was present in the nosological condition. The term “pseudomyxoma peritonei” was introduced by Werth[2] in 1884, when he described the case of a woman with gelatinous masses in the peritoneal cavity from alleged ruptured pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary, and in which he found to be pseudomucin instead of mucin. The term pseudomucin was originally used to describe the content of the locules present in ovarian pseudomucinous cystadenoma and was thought to differ from mucin. Mucin and pseudomucin were known to be composed of glycoproteins, and were differentiated by certain physical qualities[3,4].

Years later, Frankel[5] recovered the term and described the case of a man with ruptured cyst of mucinous content from the cecal appendix, the second traditional etiology for PMP, and the terminology became established in the medical literature. Several descriptions of the disease were reported thereafter. The cause of PMP was identified in the rupture of a pseudomucinous ovarian cystoma, the bursting of the appendix vemicularis, or sometimes it was thought that simultaneous processes of disease were going on in both organs, so that two distinct causes were then responsible in the same clinical case[6].

In classical descriptions, two theories were proposed to explain the PMP’s condition. Olshausen (1835-1915), a German gynecologist, discussed the hypothesis that epithelial cells from the lining of the ruptured cyst were transplanted to the peritoneum, where they took root and continued to secrete gelatinous material[7]. This theory of implantation was confronted with the theory of inflammation, where the gelatinous material irritates the peritoneum and causes a further production of similar masses[8]. The former theory is the one which has remained, but both were considered plausible even until the late 1950’s.

The real nature of the condition named pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary, or pseudomucinous cystadenomata, is an unanswered question. The term was still employed in the 1950’s[9,10], less frequently in the 1970’s[11], and is completely abandoned today. This former term could encompass the mucinous cystadenoma of the ovary but also metastatic secondary tumors. Currently, the mucinous tumors of the ovary are classified in cystadenoma, borderline tumor, mucinous carcinoma, and a new entity named seromucinous tumors[12]. None of those ovarian lesions have been described as the origin of PMP in the literature and neither in our series.

Mucins, or MUC glycoproteins, are a family of high molecular weight, glycosylated proteins, divided into membrane-associated type and secreted type. Current nomenclature discards pseudomucin and paramucin terms. The secreted MUC type is subdivided into gel-forming and non-gel-forming subtypes[13,14]. In PMP, mucin around tumor cells allows them to disseminate and redistribute within the peritoneal cavity. MUC2, a gel-forming mucin, is the most common type of mucin found in PMP gelatinous matter, and is associated with appendiceal neoplasms[15].

Pseudomyxoma is a term referring to the production of mucus free in the peritoneal cavity or in cystic gelatinous masses. The etymology of pseudo-myxoma derives from pseudomucin, which is an obsolete term in molecular biology.

PMP is a clinical syndrome and most commonly arises from the intraperitoneal spread of the mucinous appendiceal neoplasm[16] (see the Supplemental Digital Content, Video). Studies based on immunohistochemical analysis and molecular biology have demonstrated the appendiceal origin in nearly all cases of PMP, opposite to what happens when there is an ovarian involvement, which is nearly always the secondary manifestation of a primary appendiceal tumor[17].

Mucocele is not a histopathological diagnosis but as with PMP, it is a clinical description. It was first recognized as a pathological entity by Rokitansky in 1842, who described it under the term hydrops of the appendix. Later, Virchow also described the mucocele and considered it a colloid degeneration of the appendix.

The origin of PMP is usually an appendiceal neoplasm, which eventually takes the appearance of a mucocele as its clinical presentation.

Ovarian tumors as the etiology of PMP is a concept refuted nowadays. PMP does not arise from mucinous epithelial ovarian carcinoma[18]. When mucinous ovarian lesions are present in the context of PMP, a thorough analysis of histopathological features-immunohistochemistry-by the pathologist helps distinguish between primary mucinous ovarian tumors and tumors which are metastatic to the ovary (secondary lesions). The infrequent case of PMP arising from a mature ovarian cystic teratoma[19,20] is the only remaining PMP etiology from ovarian tumors.

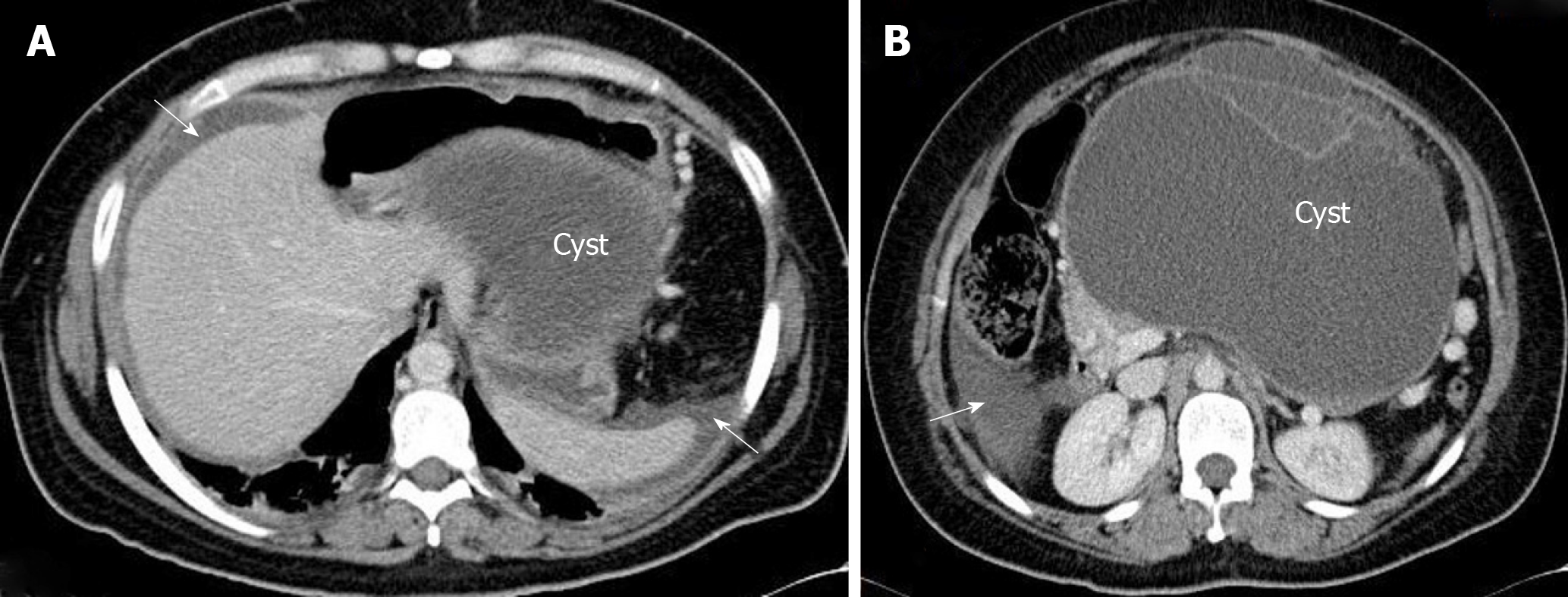

In our experience, the clinical sign of PMP (i.e., increase in abdominal girth) was present in less than 20% of the cases, over some 100 appendiceal mucinous tumors with peritoneal spread. PMP etiology in our series was appendiceal in all cases, except for one rectal cancer, two colon cancers, and one urachal cancer. There was also the case of a 37-year-old woman, who was operated on in another center, with a ruptured giant mucinous cystadenoma of the pancreas (Figure 1). Thus, the patient met the clinical criteria for PMP syndrome. The patient was referred to us because of residual peritoneal lesions, now without clinical PMP, for comprehensive treatment by cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

PMP did not arise from ovarian tumor in any case, following the final histopathological analysis. Nevertheless, more than half of the female patients referred to us with peritoneal metastases from mucinous appendiceal neoplasm had previously been operated on under the misdiagnosis of primary ovarian cancer.

In spite of all these data, it is difficult to erase the concept of ovarian origin for PMP, mainly when this concept is strengthened by the first historical reports and kept until the early 2000s.

To our knowledge, the first PMP classification is attributed to Oscar Polano[6], who, in 1901, divided the condition into two classes: The cystadenoma mucinosum peritonei simplex, representing simple superficial metastasis produced by implantation; and the cystadenoma malignum pseudomucinosum peritonei, with sharply progressive and destructive character. Almost 100 years later, the classification of Ronnett et al[21], and later the classification of Bradley et al[22], share striking similarities to that of Polano, keeping the ambiguous features that turn PMP in an elusive condition to be defined.

A variety of different classifications have been proposed, leading to confusion among this condition. PMP still appears as a distinct histologic diagnosis in the 2010 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system[23], and it is also used as a description of the macroscopic appearance of mucinous ascites.

It has been said that PMP is classified according to the histology of the peritoneal disease rather than the primary tumor. Nevertheless, the peritoneum in PMP is a target organ for metastases from a primary appendicular neoplasm or other primary tumors, not the primary origin of the disease. For instance, when metastases from colorectal adenocarcinoma are found in the liver or lung, the classification of the condition is colorectal adenocarcinoma stage IV with specific-site metastases. When those metastases are involving the peritoneum, the adenocarcinoma continues to be stage IV with peritoneal metastases. Confusion may be originating from the persistence in classifying PMP as a distinct condition from the originating cancer. The mucinous appendiceal neoplasm metastasizing to the peritoneum should be classified as stage IVa mucinous appendiceal neoplasm, which may or may not acquire the PMP appearance.

The historical doubt about malignancy of mucinous appendiceal neoplasms may be partially responsible for the confusion that remains around this condition. In the historical medical literature, it was stated that “the condition is not malignant in the sense that a carcinoma has developed, but is malignant clinically in that the condition tends toward the death of the patient”. Opinions from several authors revisited by Krivsky[6] in his review in 1917 were similar. A few examples of the opinions in that article are:

• “According to T.M. Pikin the pseudomyxoma of peritoneum is in the pathological sense benign, but clinically is not an innocent disease.”

• B.M. Leontieff is of much the same opinion considering the pseudomyxoma of the peritoneum arising from the appendix to be a benign process.

• Bailey says that ‘there is no record to my knowledge of malignancy following a pseudomucin cyst of the appendix, but by the plastic peritonitis and mechanical interference which follow such an extravasation equally dangerous conditions may develop’”.

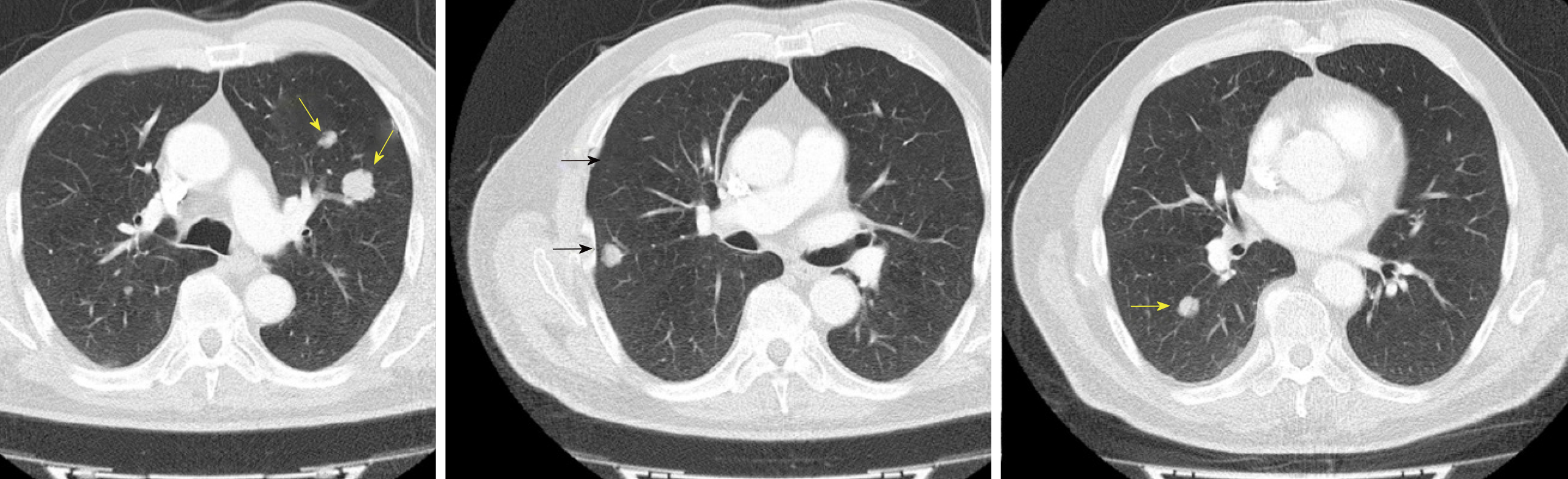

Today, peritoneal involvement of a mucinous neoplasm of the appendix is considered a malignant disease, and systemic metastases may occur. In our series, we found two patients having systemic lung metastases from low-grade appendiceal mucinous tumors (Figure 2). It is important to make distinction between these lung lesions from pleural metastases which may arise the suspicion of dissemination from diaphragmatic surfaces, mainly during surgical procedure. This kind of lung metastases has also been described by Kitai[24].

To dissipate controversies regarding PMP classifications, the PSOGI published a consensus for classification of PMP and associated appendiceal neoplasia. Participants reached a consensus on terminology for the peritoneal disease component of PMP: Low-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei; high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei; and high-grade mucinous carcinoma peritonei with signet ring cells. Broadly, there is not so much difference between this classification and that of Ronnet’s or even that of Polano’s. With this classification, the target organ, the peritoneum, is prioritized instead of the primary cancer. It remains confusing in terminology, as with the other existing classifications. The existence of several etiologies for PMP invalidates any effort of classifying PMP as a distinct entity.

In the article by Krivsky[6], it was stated that “the only correct treatment of this disease is the removal of the ruptured cystoma by surgical operation and of the colloid matter which has escaped from it into the peritoneum”. This assertion has not changed in our days. PMP is a surgical disease, with no indication for systemic chemotherapy as it is in other abdominal malignant conditions. Systemic chemotherapy should only be considered for patients who have no surgical options[25].

It had been proposed that radiotherapy should be offered to patients with PMP, and that opinion was employed until the 1990s[26]. However, this therapeutic option is not considered currently.

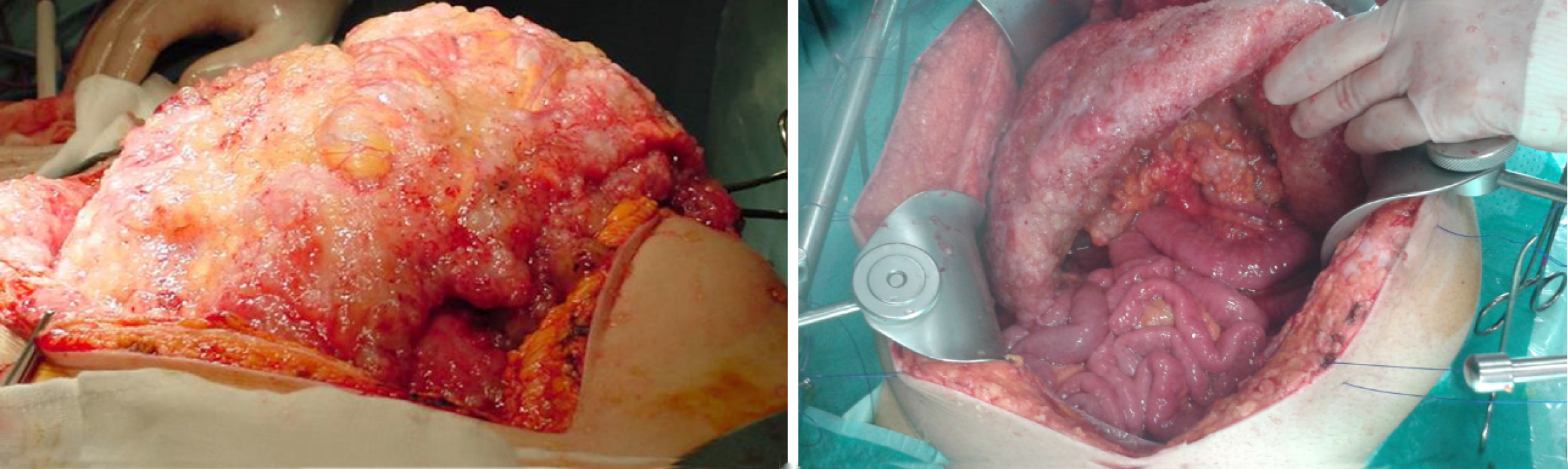

In the therapeutic armamentarium, surgery has remained the most reliable treatment to cure or prolong survival in those patients. Nevertheless, it was not until the development of the CRS concept, coupled with the administration of HIPEC, that surgical treatment took its principal role in the management of PMP. The rational for the procedure of CRS was the complete removal of the visible disease employing peritonectomy techniques, based on the redistribution phenomenon. This phenomenon was hypothesized by Sugarbaker[27] in the 1990s, and refers to the observation that large amounts of tumor will be found at some predetermined anatomic sites within the abdominal cavity, allowing for sparing of other sites. The anatomic sites targeted for this redistribution event are mainly the greater omentum, with the highest extent being the omental cake (Figure 3), the undersurface of the right diaphragm, the Douglas pouch, the Morison pouch, the left colonic gutter, and the ligament of Treitz. The limitation for complete CRS is the massive involvement of the small bowel, particularly due to iterative procedures with creation of scars where tumors infiltrate. Even when the tumor volume is high, the cytoreduction may result in benefit for overall survival[28].

The introduction of chemotherapy agents locally applied into the peritoneum goes back to the experience reported by Economou et al[29] in 1957. These authors employed nitrogen mustard in 36 patients with tumors of the breast, colon, rectum, and stomach, and injected the agent into a branch of the portal vein, or by leaving it in the peritoneal cavity at the end of the operation, or via use of both techniques.

Spratt in the 1980s renewed the intraperitoneal chemotherapy procedure, and Sugarbaker[27] developed it in the 1990s.

Nevertheless, PMP is usually derived from cells of low-grade malignancy, with poor aggressive behavior in terms of growth rate and systemic metastasis. Theoretically, these cells will show a poor response to chemotherapy agents, which acts over the cellular vital cycle. Thus, the effect of the intraperitoneal chemotherapy agent of HIPEC may be of lesser value than thought. The hyperthermic effect of HIPEC with an independent cytolytic action has not been assessed in randomized trials.

In rare cases that PMP arises from mucinous colon adenocarcinoma, the cytotoxic drugs may enhance radicality of the procedure. The PRODIGE 7 study, a multicenter randomized French trial which compared CRS alone with CRS combined with HIPEC using oxaliplatin in patients with colon peritoneal carcinomatosis, failed to demonstrate an overall survival advantage in the oxaliplatin arm. However, the impressive mean overall survival of more than 40 mo in both groups (41.7 mo vs 41.2 mo in the HIPEC and control arms, respectively) must be emphasized (results presented in ASCO 2018)[30].

The etymology of PMP derives from the presence of mucin and mucin neoplastic cells spreading in the peritoneal cavity. The origin of the disease is a leaking or ruptured neoplasm of the appendix in the majority of cases. When mucinous metastases in the peritoneal cavity are thought to arise from an ovarian neoplasm, appendiceal and gastrointestinal mucinous adenocarcinoma must be ruled out. The cytoreductive techniques described in the CRS/HIPEC procedure have become of extreme value in the management of patients with manifest PMP.

I would like to thank Professor Bruno Camps for sharing those years throughout these difficult surgical procedures, those being cytoreductive surgery of peritoneal carcinomatosis, at the Hospital Clinico Universitario de Valencia.

Author contributions: Morera-Ocon FJ designed the study, collected the reference articles, and wrote the manuscript; Navarro-Campoy C helped write the paper, with emphasis in the gynecological aspects of the text.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Isik A, Rubbini M, Vagholkar KR S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhou BX

| 1. | Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Sobin LH, Sugarbaker PH, González-Moreno S, Taflampas P, Chapman S, Moran BJ; Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International. A Consensus for Classification and Pathologic Reporting of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Associated Appendiceal Neoplasia: The Results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:14-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 543] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Werth K. Klinische und anatomische Untersuchungen zur Lehre von den Bauchgeschwülsten und der Laparotomie. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 1884;84:100-118. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Maki M. Biochemical studies on carbohydrates. The Tohoka J Exp Med. 1952;55:311-331. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Reagan JW. Histopathology of ovarian pseudomucinous cystadenoma. Am J pathol. 1949;25:689-707. |

| 5. | Frankel E. Uher das sogenaute pseudomyxoma peritonei. Med Wochenschr. 1901;48:965-970. |

| 6. | Krivsky LA. On the pseudomyxoma peritonei. BJGO. 1921;28:204-227. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weaver CH. Mucocele of the appendix with Pseudomucinous Degeneration. Ame J Surg. 1937;36:523-526. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jorgensen MB. Ruptured mucocele of the appendix with pseudomyxoma peritonei, simulating pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary. Cal Med. 1949;70:46-47. |

| 9. | Towers RP. A note on the origin of the pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary. J Obstect Gynaecol Br Emp. 1956;63:253-54. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | SHAW ES. Ruptured multilocular pseudomucinous cystadenoma of the ovary with pleural effusion. Am J Surg. 1953;86:107-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Loung KC. Pseudo-Meigs' syndrome associated with a pseudomucinous cystadenoma. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:631-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meinhold-Heerlein I, Fotopoulou C, Harter P, Kurzeder C, Mustea A, Wimberger P, Hauptmann S, Sehouli J. The new WHO classification of ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer and its clinical implications. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:695-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gum JR. Mucin genes and the proteins they encode: structure, diversity, and regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:557-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:245-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 742] [Cited by in RCA: 780] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | O'Connell JT, Hacker CM, Barsky SH. MUC2 is a molecular marker for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:958-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ansari N, Chandrakumaran K, Dayal S, Mohamed F, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in 1000 patients with perforated appendiceal epithelial tumours. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:1035-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Szych C, Staebler A, Connolly DC, Wu R, Cho KR, Ronnett BM. Molecular genetic evidence supporting the clonality and appendiceal origin of Pseudomyxoma peritonei in women. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1849-1855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Perren TJ. Mucinous epithelial ovarian carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2016;27 Suppl 1:i53-i57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pranesh N, Menasce LP, Wilson MS, O'Dwyer ST. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: unusual origin from an ovarian mature cystic teratoma. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:1115-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | McKenney JK, Soslow RA, Longacre TA. Ovarian mature teratomas with mucinous epithelial neoplasms: morphologic heterogeneity and association with pseudomyxoma peritonei. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:645-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ronnett BM, Zahn CM, Kurman RJ, Kass ME, Sugarbaker PH, Shmookler BM. Disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis and peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis. A clinicopathologic analysis of 109 cases with emphasis on distinguishing pathologic features, site of origin, prognosis, and relationship to "pseudomyxoma peritonei". Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1390-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 22. | Bradley RF, Stewart JH 4th, Russell GB, Levine EA, Geisinger KR. Pseudomyxoma peritonei of appendiceal origin: a clinicopathologic analysis of 101 patients uniformly treated at a single institution, with literature review. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:551-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Carr NJ, Sobin LH, Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds. Adenocarcinoma of the appendix. Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, eds . WHO classification of tumors of the digestive system. Lyon: IARC; 2010; 122-125. |

| 24. | Kitai T. Pulmonary metastasis from pseudomyxoma peritonei. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:690256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Morera Ocon FJ, Camps Vilata B. Systemic chemotherapy in appendeal adenocarcinomas with peritoneal metastases. Is it worth it? AMS. 2019;2:3-9. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gough DB, Donohue JH, Schutt AJ, Gonchoroff N, Goellner JR, Wilson TO, Naessens JM, O'Brien PC, van Heerden JA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Long-term patient survival with an aggressive regional approach. Ann Surg. 1994;219:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sugarbaker PH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. A cancer whose biology is characterized by a redistribution phenomenon. Ann Surg. 1994;219:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Delhorme JB, Elias D, Varatharajah S, Benhaim L, Dumont F, Honoré C, Goéré D. Can a Benefit be Expected from Surgical Debulking of Unresectable Pseudomyxoma Peritonei? Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:1618-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Economou SG, Mrazek R, Mcdonald G, Slaughter D, Cole WH. The intraperitoneal use of nitrogen mustard at the time of operation for cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1958;68:1097-1102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Quenet F, Elias D, Roca L, Goere D, Ghouti L, Pocard M, Facy M, Arvieux C, Lorimier G, Pezet D, Marchal F, Loi V, Meeus P, De Forges H, Stanbury T, Paineau J, Glehen O. UNICANCER phase III trial of hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC): PRODIGE 7. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36 (18)_ suppl, LBA3503-LBA3503. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |