Published online Apr 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i4.218

Peer-review started: March 4, 2019

First decision: March 19, 2019

Revised: March 23, 2019

Accepted: April 9, 2019

Article in press: April 9, 2019

Published online: April 27, 2019

Processing time: 55 Days and 10.8 Hours

Controversy exists regarding the impact of preoperative bowel preparation on patients undergoing colorectal surgery. This is due to previous research studies, which fail to demonstrate protective effects of mechanical bowel preparation against postoperative complications. However, in recent studies, combination therapy with oral antibiotics (OAB) and mechanical bowel preparation seems to be beneficial for patients undergoing an elective colorectal operation.

To determine the association between preoperative bowel preparation and postoperative anastomotic leak management (surgical vs non-surgical).

Patients with anastomotic leak after colorectal surgery were identified from the 2013 and 2014 Colectomy Targeted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database and were employed for analysis. Every patient was assigned to one of three following groups based on the type of preoperative bowel preparation: first group-mechanical bowel preparation in combination with OAB, second group-mechanical bowel preparation alone, and third group-no preparation.

A total of 652 patients had anastomotic leak after a colectomy from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2014. Baseline characteristics were assessed and found that there were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in terms of age, gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, and other preoperative characteristics. A χ2 test of homogeneity was conducted and there was no statistically/clinically significant difference between the three categories of bowel preparation in terms of reoperation.

The implementation of mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotic use in patients who are going to undergo a colon resection does not influence the treatment of any possible anastomotic leakage.

Core tip: Anastomotic leak after colon resection contributes significantly to postoperative morbidity and mortality. Surgeons are constantly seeking ways to decrease the rate of the anastomotic leak by optimizing the patient before the operation. Currently the preoperative bowel preparation constitutes a significant field of debate. We aimed to determine the association between preoperative bowel preparation and postoperative anastomotic leak management, surgical versus non-surgical. We found that the implementation of mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotic use in patients who are going to undergo a colon resection does not influence the treatment of any possible anastomotic leakage.

- Citation: Zorbas KA, Yu D, Choudhry A, Ross HM, Philp M. Preoperative bowel preparation does not favor the management of colorectal anastomotic leak. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(4): 218-228

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i4/218.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i4.218

Anastomotic leak after colon resection is one of the feared complications in general surgery, with a reported incidence in the literature varying as broadly as 3.4% to 40%[1]. An acceptable overall leak rate among experienced colorectal surgeons is between 3% and 6%[2]. Anastomotic leak contributes significantly to postoperative morbidity and mortality, and it also increases the risk of local recurrence for cancer patients[1,3,4]. Several risk factors have been linked to anastomotic leakage, both preoperative and intraoperative. Examples include emergent operation, a high American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, age greater than 70 years, low serum albumin, prolonged operative time, body mass index (BMI), and several others[2,5-7]. For these reasons, surgeons are constantly seeking ways to decrease the rate of the anastomotic leak, as well as its consequences, by optimizing the patient before the operation.

The idea of preoperative bowel preparation with oral antibiotics (OAB) before an elective colon resection was first proposed by Poth et al[8] in 1942. Later in 1971, Nichols et al[9] introduced the combination of mechanical bowel preparation with OAB prior to elective colon surgery with the intent of reducing intraluminal fecal bulk and increasing delivery of antibiotics to colonic mucosa. Since then this combination has been regarded as an effective strategy for preventing anastomotic leak[9]. The benefit of this combination with the more widespread adoption of intravenous perioperative antibiotics, however, has been contested, as numerous studies have failed to demonstrate a protective effect against postoperative complications. Currently the optimal preoperative bowel preparation constitutes a significant field of debate[10]. More recent observational studies indicate that administration of combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation (MBP) and OAB offers a protective effect by significantly reducing the incidence of anastomotic leaks, surgical site infection, and mortality[3,11].

There is a variable clinical presentation of anastomotic leakage. Ranging from full luminal dehiscence with peritonitis, localized abscess, or subclinical leak with omental or serosal seal, often associated with ileus or systemic inflammatory response. We hypothesized that administration of MBP + OAB, by reducing and altering luminal bacterial content may diminish the clinical severity of anastomotic leak. There is evolving evidence that the amount and species of intestinal bacteria play an important role in anastomotic healing[4]. We aimed to determine the association between preoperative bowel preparation and postoperative anastomotic leak management. Building upon the protective role of MBP and OAB in the incidence of leakage, we hypothesized that patients experiencing anastomotic leaks following preoperative bowel preparation would be less likely to require reoperation for leak management.

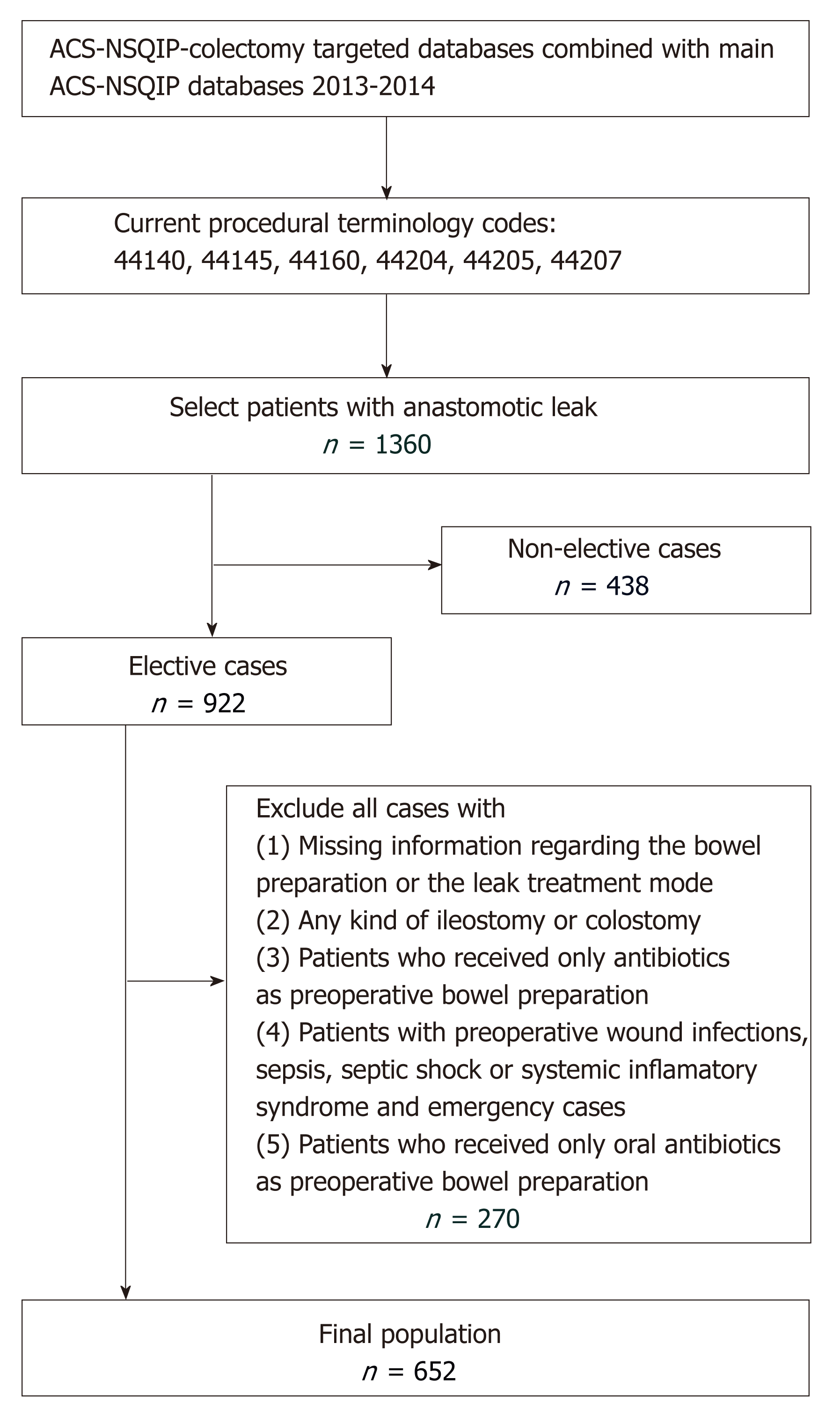

The 2013 and 2014 Colectomy Targeted American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) databases were merged with the 2013 and 2014 ACS-NSQIP Participant User File (PUF) databases, and both were used to carry out this study. NSQIP collects information in a retrospective manner on more than 150 variables, including preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative variables for patients undergoing major surgical procedures in both the inpatient and outpatient settings. NSQIP database benefits from several unique features of data collection, i.e., the trained/certified collectors, the standardized variable definitions, and the diversity of participating hospitals in the program (more than 400). Complete details of NSQIP database have been published by Khuri et al[12] in 1998. Patients were included in this study if they underwent a colorectal resection with anastomosis creation [current procedural codes (CPT) were 44140: Colectomy, partial; with anastomosis; 44145: Colectomy, partial, with coloproctostomy (low pelvic anastomosis); 44160 Colectomy, partial, with removal of terminal ileum with ileocolostomy; 44204 Laparoscopy, surgical colectomy, partial, with anastomosis; 44205 Laparoscopy, surgical colectomy, partial, with removal of terminal ileum with ileocolostomy; 44207 Laparoscopy, surgical colectomy, partial, with anastomosis, with coloproctostomy, low pelvic anastomosis] and subsequently had a postoperative anastomotic leak. As anastomotic leak was defined as leak of enteral content through an anastomosis and it was determined by the colectomy targeted database. Detailed information for the preoperative bowel preparation and the treatment mode of the leak complication were extracted from the Colectomy Targeted ACS-NSQIP databases, while information regarding the patients’ baseline characteristics was obtained from the ACS-NSQIP PUF database. Patients without anastomosis or postoperative leak were excluded from our analysis. Patients were also excluded if they had undergone a non-elective operation, had any kind of ileostomy or colostomy, or had missing information regarding the bowel preparation or the leak treatment mode. Patients who received only antibiotics as preoperative bowel preparation were also excluded because it is not a common practice and the number of such patients was relatively small. These resulted in a final population of 652 patients for our study. The flowchart of the patient selection is depicted in Figure 1. The NSQIP data base is a de-identified patient database and consequently our study was exempt from institutional review board (IRB) approval.

The primary outcome, a dichotomous categorical variable, was the clinical treatment modality (surgical vs non-surgical) of a patient with a postoperative anastomotic leak. As the primary predictor variable, we considered the preoperative bowel preparation, which was defined as a discrete variable with three categories: (1) MBP + OAB; (2) MBP alone; and (3) no preparation. Secondary predictor variables included patient’s age, gender, BMI, race (which had the following three groups: (1) Caucasian; (2) African American; and (3) Other: (Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and Unknown), ASA score, diabetes mellitus status, preoperative steroid use, current smoking status, preoperative history of hypertension requiring treatment, preoperative weight loss > 10% in the last six months, preoperative history of bleeding disorder, type of operation based on the CPT code, preoperative chemotherapy, primary indication for surgery, preoperative anemia of patient by using the patient hematocrit, preoperative inflammation status of patient by using the preoperative white blood cells count, preoperative hemostasis status by using the patient’s platelets count, the preoperative nutritional status by using the serum albumin level, and patient’s renal function by using the serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN).

Baseline characteristics of all patients in the three preoperative bowel preparation groups were assessed and compared, with the intention to detect any significant differences among the three groups that could potentially confound or modify the effect of preoperative bowel preparation on the primary outcome. Data on categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions (%) and were compared between groups using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. Data on continuous variables are summarized with the usual descriptive statistics such as mean ± SD, medians (ranges), and interquartile ranges; and group comparisons of these variables were performed using the Wilcoxon Test (for two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis (for three or more groups) test due to the fact that data contained outliers and were unlikely to follow a normal distribution. Univariable logistic regression models were used to examine the associations of individual predictor variables with the primary outcome one at a time. Finally, multivariable logistic regression was performed to ascertain the effects of all potential predictor variables on the likelihood of patients being treated with reoperation for the leak. Unadjusted raw or adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported as appropriate. Two-tailed P-values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. SPSS version 24 and SAS version 9.3 were used for all the data analyses.

Among 652 patients undergoing elective colon resection, with anastomotic leak, between January 2013 and December 2014, 163 (25%) received mechanical bowel preparation combined with OAB before the operation, 260 (39.9%) received only mechanical bowel preparation, and 229 (35.1%) received no preoperative bowel preparation. The baseline characteristics of the final study population are described in Table 1: Mean (SD) population age was 59.5 (14.7) years, the average (SD) BMI of the population was 28.7 (7.0), 58.3% of the patients were males, 483 (74.1%) patients were of White race, 97 (14.9%) patients had diabetes mellitus preoperatively, and 66 (10.1%) patients were taking steroids preoperatively. There were no statistically significant differences between the three bowel preparation groups concerning age, gender, BMI, ASA score, diabetes mellitus, steroid use, smoking status, hypertension, bleeding disorder, preoperative chemotherapy, and indication for surgery (Table 1). However, a statistically significant racial difference among those three groups existed, that is, the lowest percentage of White patients in the no preparation group 65.1% (No Prep) compared with the other two groups: 73.6% in MBP + OAB and 82.3% in MBP (Table 1). A significant difference was found also in the distribution of CPT codes among the three groups (Table 1). Furthermore, all three groups were similar from the standpoint of preoperative inflammatory status (White blood cell counts), preoperative patient’s hematocrit, preoperative coagulant status (patient’s platelets), preoperative nutritional status (serum albumin), and preoperative renal function (BUN) (Table 1).

| MBP + OAB | MBP | No Prep | Overall | P value | |

| Overall N (missing data) | n = 163 (25%) | n = 260 (39.9%) | n = 229 (35.1%) | n = 652 (100%) | |

| Age (missing: 3/0.5%) | |||||

| mean (SD) | 57.69 (14.69) | 60.61 (13.7) | 59.48 (15.64) | 59.48 (14.67) | |

| Median | 60 | 61 | 60 | 61 | 0.26 |

| Q1/Q3 | 47/69 | 52/71 | 49.25/72 | 50/71 | |

| Age grouped n (%) | |||||

| ≥ 65 yr | 60 (37) | 104 (40.2) | 98 (43) | 262 (40.4) | 0.50 |

| Gender (missing: 0%) | |||||

| Female | 60 (36.8) | 110 (42.3) | 102 (44.5) | 272 (41.7) | 0.30 |

| Male | 103 (63.2) | 150 (57.7) | 127 (55.5) | 380 (58.3) | |

| BMI (missing: 2/0.3%) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 28.65 (6.81) | 28.94 (7.43) | 28.52 (6.74) | 28.72 (7.04) | |

| Median | 27.05 | 27.60 | 27.89 | 27.75 | 0.96 |

| Q1/Q3 | 24.23/32.03 | 24.06/32.35 | 23.4/32.28 | 23.9/32.15 | |

| Race (missing: 0%) | |||||

| White | 120 (73.6) | 214 (82.3) | 149 (65.1) | 483 (74.1) | < 0.001 |

| AA | 21 (12.9) | 11 (4.2) | 18 (7.9) | 50 (7.7) | |

| Other or unknown | 22 (13.5) | 35 (13.5) | 62 (27.1) | 119 (18.3) | |

| ASA score (missing: 0%) | |||||

| 1-no disturb | 3 (1.8) | 3 (1.2) | 9 (3.9) | 15 (2.3) | 0.34 |

| 2-mild disturb | 68 (41.7) | 110 (42.3) | 91 (39.7) | 269 (41.3) | |

| 3-severe disturb | 86 (52.8) | 139 (53.5) | 116 (50.7) | 341 (52.3) | |

| ≥ 4-life threat | 6 (3.7) | 8 (3.1) | 13 (5.7) | 27 (4.1) | |

| Diabetes mellitus (missing: 0%) | 30 (18.4) | 30 (11.5) | 37 (16.2) | 97 (14.9) | 0.12 |

| Preoperative steroid use (missing: 0%) | 23 (14.1) | 18 (6.9) | 25 (10.9) | 66 (10.1) | 0.05 |

| Current smoking status (missing: 0%) | 33 (20.2) | 60 (23.1) | 40 (17.5) | 133 (20.4) | 0.31 |

| Hypertension requiring treatment (missing: 0%) | 83 (50.9) | 125 (48.1) | 110 (48) | 318 (48.8) | 0.82 |

| Preoperative weight loss > 10% in last six months (missing: 0%) | 15 (9.2) | 11 (4.2) | 9 (3.9) | 35 (5.4) | 0.04 |

| Preoperative bleeding disorder (missing: 0%) | 5 (3.1) | 7 (2.7) | 5 (2.2) | 17 (2.6) | 0.86 |

| Current procedural code | |||||

| 44140 | 23 (14.1) | 56 (21.5) | 46 (20.1) | 125 (19.2) | 0.007 |

| 44145 | 25 (15.3) | 39 (15) | 33 (14.4) | 97 (14.9) | |

| 44160 | 15 (9.2) | 17 (6.5) | 34 (14.8) | 66 (10.1) | |

| 44204 | 47 (28.8) | 53 (20.4) | 46 (20.1) | 146 (22.4) | |

| 44205 | 20 (12.3) | 21 (8.1) | 28 (12.2) | 69 (10.6) | |

| 44207 | 33 (20.2) | 74 (28.5) | 42 (18.3) | 149 (22.9) | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy (missing: 2/0.3%) | 19 (11.8) | 20 (7.7) | 23 (10.0) | 62 (9.5) | 0.36 |

| Continue in next page | |||||

| Primary indication for surgery (missing: 0%) | |||||

| Colon cancer | 68 (41.7) | 127 (48.8) | 112 (48.9) | 307 (47.1) | 0.06 |

| Non-malignant polyp | 16 (9.8) | 32 (12.3) | 23 (10) | 71 (10.9) | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 13 (8) | 9 (3.5) | 22 (9.6) | 44 (6.7) | |

| Acute diverticulitis | 10 (6.1) | 14 (5.4) | 10 (4.4) | 34 (5.2) | |

| Chronic diverticular disease | 37 (22.7) | 41 (15.8) | 27 (11.8) | 105 (16.1) | |

| Other | 19 (11.7) | 37 (14.2) | 35 (15.3) | 91 (14) | |

| Preoperative hematocrit (%) (missing: 30/4.6%) | |||||

| n | 153 (93.9) | 247 (95) | 222 (96.9) | 622 (95.4) | |

| mean (SD) | 38.95 (5.55) | 39.14 (5.48) | 38.36 (5.64) | 38.82 (5.56) | |

| Median | 39 | 39.5 | 39 | 39.2 | 0.38 |

| Q1/Q3 | 35.6/42.9 | 35.8/43 | 34.1/42 | 35.4/42.7 | |

| Preoperative white blood cells (K/cumm) (missing: 37/5.7%) | |||||

| n | 150 (92) | 244 (93.8) | 221 (96.5) | 615 (94.3) | |

| mean (SD) | 7.47 (2.71) | 7.52 (2.57) | 7.65 (2.43) | 7.56 (2.55) | |

| Median | 7.1 | 7 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 0.48 |

| Q1/Q3 | 5.68/8.8 | 5.7/8.84 | 6/9 | 5.8/8.9 | |

| Preoperative platelets (K/cumm) (missing: 39/6%) | |||||

| n | 150 (92) | 244 (93.8) | 219 (95.6) | 613 (94) | |

| mean (SD) | 265 (102) | 256 (91) | 267 (95) | 262 (95.42) | |

| Median | 253 | 247 | 258 | 252 | 0.59 |

| Q1/Q3 | 203/301 | 195/301 | 206/304 | 201/301 | |

| Preoperative serum albumin (g/dL) (missing: 243/37.3%) | |||||

| n | 112 (68.7) | 164 (63.1) | 133 (58.1) | 409 (62.7) | |

| mean (SD) | 3.83 (0.57) | 3.91 (0.53) | 3.89 (0.62) | 3.88 (0.57) | 0.50 |

| Median | 3.9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Q1/Q3 | 3.5/4.3 | 3.6/4.3 | 3.6/4.3 | 3.6-4.3 | |

| Preoperative blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) (missing: 77/11.8%) | |||||

| n | 149 (91.4) | 231 (88.8) | 195 (85.2) | 575 (88.2) | |

| mean ± SD | 14.67 ï¼8.99ï¼ | 15.32 (8.55) | 14.17 (6.20) | 14.8 (7.96) | |

| Median | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 0.18 |

| Q1/Q3 | 10/16.4 | 11/17 | 10/17.7 | 10/17 | |

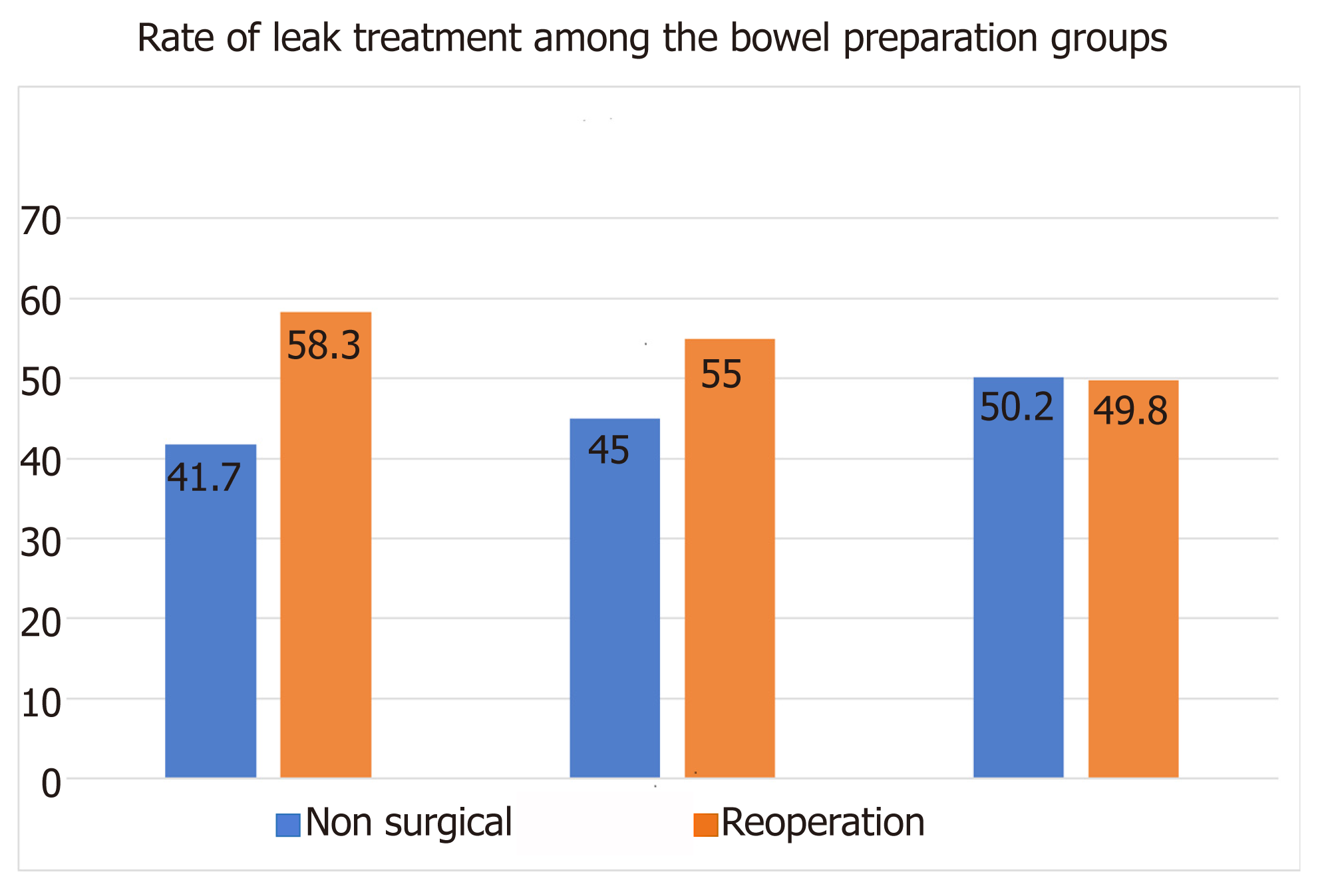

The overall rate of reoperation for leak treatment among the three groups of preoperative bowel preparation was quite impressive: 54%. A similar rate was found in the initial NSQIP database before applying our exclusive criteria. This was entirely opposite to what we had expected, bearing in mind the theoretical protective effect of the bowel preparation on the anastomotic leak. The rate of reoperation was higher in both groups of bowel preparation (MBP + OAB: 58.3% and MBP: 55%) compared with that in the no preparation group (49.8%) (Figure 2). However, these differences among the three bowel preparation groups did not reach the level of the conventional statistical significance (P = 0.23), and we cannot reject the null hypothesis of having the same reoperation rate in the three bowel preparation groups. Furthermore, 95 (58.3%) patients in the group of MBP + OAB, 143 (55%) patients in the group of MBP, and 114 (49.8%) patients in the group of no preparation underwent a second operation as the treatment of anastomosis leak. A univariable logistic regression using the three groups was performed and revealed a slightly lower, albeit not statistically significantly different, odds ratio of reoperation in those patients who received no preparation compared with those who received either MBP alone or MBP + OAB as well as a slightly lower, but not statistically significantly different, odds ratio in those patients who received MPB compared with those who received MBP + OAB (Table 2).

| Variable | Univariable logistic regression model | P-value | ||

| NWAD | uOR | 95%CI | ||

| Bowel Prep groups | ||||

| MBP vs MBP + OAB1 | 652 (100) | 1.14 | 0.77-1.70 | 0.51 |

| Nothing vs MBP1 | 1.23 | 0.86-1.76 | 0.25 | |

| Nothing vs MBP + OAB1 | 1.41 | 0.94-2.11 | 0.10 | |

| Age < 65 vs ≥ 65 yr1 | 649 (99.5) | 0.82 | 0.60-1.12 | 0.21 |

| BMI ≥ 30 vs < 301 | 650 (99.7) | 1.44 | 1.03-2.00 | 0.03 |

| Female vs male | 652 (100) | 1.35 | 0.99-1.85 | 0.06 |

| Non-White vs White | 652 (100) | 1.08 | 0.76-1.53 | 0.69 |

| No DM vs DM1 | 652 (100) | 0.85 | 0.55-1.31 | 0.46 |

| No steroid vs steroids1 | 652 (100) | 0.89 | 0.54-1.49 | 0.67 |

| Hct (%) < 38 vs ≥ 381 | 622 (95.4) | 0.93 | 0.67-1.29 | 0.68 |

| WBC (K/cumm) ≤ 12 vs > 121 | 615 (94.3) | 1.53 | 0.74-3.16 | 0.26 |

| PLT (K/cumm) < 150 vs ≥ 1501 | 613 (94) | 1.58 | 0.75-3.37 | 0.23 |

| Albumin (g/dL) < 3.5 vs ≥ 3.51 | 409 (62.7) | 1.13 | 0.70-1.83 | 0.62 |

| BUN (mg/dL) > 20 vs ≤ 201 | 575 (88.2) | 1.17 | 0.73-1.88 | 0.53 |

Other variables were also examined using univariable logistic regression for their potential associations with reoperation, but the only statistically significant predictor was BMI: a 44% increased odds of reoperation in patients with BMI ≥ 30 compared with those with BMI < 30 [OR (95%CI): 1.44 (1.03, 2.00); P = 0.03; Table 2]. Multiple logistic regression, however, did not produce further insights in predicting the odds of reoperation as a clinical management of anastomotic leak beyond that of the association of BMI and reoperation in our study population. On the other hand, between the two groups of leak treatment (Non-Surgical vs Reoperation), there were only two statistically significant differences: about 10 pounds of higher weight but only a slightly, non-significant higher BMI in the group of reoperations when compared to the non-surgical group and a statistically significant higher rate of preoperative blood transfusion in the group of reoperation (Table 3). The Non-Surgical and Reoperation groups were not statistically different regarding age, height, BMI, gender, race, diabetes mellitus, preoperative steroid use, ASA classification, and weight loss >10% in the last six months (Table 3). The difference in gender between non-surgical and reoperation groups was borderline significant (female: 45.7% vs 38.4% for non-surgical vs reoperation groups; P = 0.06).

| Anastomosis leak treatment groups | ||||

| Non-surgical (n = 300) | Reoperation (n = 352) | Total (n = 652) | P-value | |

| Age | ||||

| NWAD (%) | 300 (100) | 349 (99.1) | 649 (99.5) | 0.891 |

| mean ± SD | 59.38 ± 15.1 | 59.57 ± 14.31 | 59.48 ± 14.67 | |

| Median (range) Q1/Q3 | 61 (19-88) 50/71 | 60 (21-89) 51/70 | 61 (19-89) 50/71 | |

| Height (inches) | ||||

| NWAD (%) | 298 (99.3) | 352 (100) | 650 (99.7) | 0.191 |

| mean ± SD | 66.39 ± 4.02 | 66.8 ± 3.68 | 66.61 ± 3.84 | |

| Median (range) Q1/Q3 | 66.5 (54-80) 64/69 | 67 (57-76) 64/70 | 67 (54-80) 64/69 | |

| Weight (lbs) | ||||

| NWAD (%) | 299 (99.7) | 352 (100) | 651 (99.8) | 0.021 |

| mean ± SD | 176 ± 44.29 | 186 ± 51.7 | 182 ± 48.65 | |

| Median (range) Q1/Q3 | 172 (95-360) 144/201 | 179 (83-469) 149/217 | 175 (83-469) 145/208 | |

| BMI | ||||

| NWAD (%) | 298 (99.3) | 352 (100) | 650 (99.7) | 0.131 |

| mean ± SD | 27.99 ± 5.79 | 29.34 ± 7.89 | 28.72 ± 7.04 | |

| Median (range) Q1/Q3 | 27.12 (17.1-48.8) 23.9/31.3 | 28.1 (13.4-68.2) 23.9/33.3 | 27.75 (13-68) 23.9-32.15 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 137 (45.7) | 135 (38.4) | 272 (41.7) | 0.062 |

| Male | 163 (54.3) | 217 (61.6) | 380 (58.3) | |

| Race | ||||

| White | 220 (73.3) | 263 (74.7) | 483 (74.1) | 0.692 |

| Non-White | 80 (26.7) | 89 (25.3) | 169 (25.9) | |

| DM | ||||

| Yes | 48 (16) | 49 (13.9) | 97 (14.9) | 0.462 |

| No | 252 (84) | 303 (86.1) | 555 (85.1) | |

| Steroids use | ||||

| Yes | 32 (10.7) | 34 (9.7) | 66 (10.1) | 0.672 |

| No | 268 (89.3) | 318 (90.3) | 586 (89.9) | |

| ASA Score | ||||

| ≤ 2 | 133 (44.3) | 151 (42.9) | 284 (43.6) | 0.712 |

| ≥ 3 | 167 (55.7) | 201 (57.1) | 368 (56.4) | |

| Weight loss >10% | ||||

| Yes | 13 (4.3) | 22 (6.3) | 35 (5.4) | 0.282 |

| No | 287 (95.7) | 330 (93.7) | 617 (94.6) | |

| PRTR | ||||

| No | 300 (100) | 346 (98.3) | 646 (99.1) | 0.033 |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 6 (1.7) | 6 (0.9) | |

In our study, we assessed the impact of preoperative bowel preparation on the ma-nagement of postoperative anastomotic leak using the NSQIP database. We hypothesized that MBP + OAB bowel preparation may alter the microbiome and confer a protective clinical effect in the case of an anastomotic leak. However, we found that patients with postoperative anastomotic leakage are not affected favorably with preoperative bowel preparation. Conversely, we found that patients with anastomotic leak who took any form of bowel preparation exhibit a slightly higher rate of reoperation compared to patients who did not undergo any preparation. However, this difference did not reach the statistical significance.

For over a century, bowel preparation has been the standard of care in elective colorectal surgery[10]. However, several studies demonstrated that, as an independent variable, MBP is not only an ineffective protective measure, but also may have deleterious effects on patient’s health and healing. Contant et al[5] published a multicenter retrospective controlled trial with 1345 patients, which showed no significant difference in the rate of anastomotic leaks between patients who received MBP (n = 670) and those who did not receive bowel preparation (n = 684). Another retrospective controlled trial with 1343 participants yielded similar results and it was published by Jung et al[7]. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial by Bucher et al[13] found significant adverse effects associated with MBP, e.g., loss of superficial mucus and inflammatory changes (polymorphonuclear and lymphocytes cells infiltration). Finally, there have also been several case reports of bowel preparation associated adverse effects, such as electrolyte abnormalities (hyponatremia, hypernatremia, hypocalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, etc.) and seizures[14-17]. On the other hand, combination therapy with oral AB and MBP seems to be beneficial for patients undergoing an elective colorectal operation according to the more recent observational database studies. Specifically, Scarboroug et al[3] performed an analysis of ACS-NSQIP Colectomy-Targeted datasets and found a significantly lower incidence of anastomotic leakage (MBP/OAB: 2.8% vs No Preparation: 5.7%, P = 0.001), a lower procedure related hospital readmission (MBP/OAB: 5.4% vs No Preparation: 7.9%, P = 0.03), and a lower thirty-day incidence of postoperative incisional surgical site infection (MBP/OAB: 3.2% vs No Preparation: 9.0%, P < 0.001) in patients who had received MBP and OAB compared to those who did not[3]. Also, Kiran et al[11] performed an analysis of ACS-NSQIP dataset in 2012 and found that MBP with OAB was associated with a reduced rate of anastomotic leak compared with the no preparation group.

Undoubtedly there are several notable limitations in our study, both in the database construction and in the data extraction. First, we were not able to distinguish which types of MBP or antibiotics were used. Both are significant, as different preparations have different adverse effects profiles and certain antibiotics have been associated with the development of very serious complications such as pseudomembranous colitis, which can impact complication management. Secondly, we cannot verify whether all patients received antibiotics as a prophylactic measure or due to a concurrent infection. This has the potential to radically impact our hypothesis and study findings, as some patients could have been in an inflammatory state prior to the operation. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the preoperative white blood cell counts among the three bowel preparation groups, an indication that went along well with our hypothesis of patients receiving the antibiotics primarily as a prophylactic measure rather than for a concurrent preoperative infection. Furthermore, we are not able to confirm the exact order of MBP and AB administration in patients. Finally, this study is subjected to all potential limitations and bias that a retrospective study could have.

Our study constitutes the first report concerning the association between bowel preparation and anastomotic leak treatment (for malignant and non-malignant cases). Although we did not find an advantageous impact of the bowel preparation on anastomotic leakage treatment, a prospective controlled trial with the same query would be a more reliable source to draw stronger conclusions on this topic. However, with the findings of this study we think that the clinical decision on the further treatment of anastomotic leak should not be influenced by the patient’s preoperative bowel preparation.

Controversy exists regarding the impact of preoperative bowel preparation on patients undergoing colorectal surgery. This is due to previous research studies, which fail to demonstrate protective effects of mechanical bowel preparation against postoperative complications.

However, in recent studies, combination therapy with oral antibiotics (OAB) and mechanical bowel preparation seems to be beneficial for patients undergoing an elective colorectal operation.

We aimed to determine the association between preoperative bowel preparation and postoperative anastomotic leak management (surgical vs non-surgical). We hypothesized that patients experiencing anastomotic leaks, following preoperative bowel preparation, would less likely require reoperation for the leak management.

We performed a retrospective analysis of patients who had a colorectal resection with anastomosis creation and subsequently developed anastomotic leak. Every patient was assigned to one of three following groups based on the type of preoperative bowel preparation: first group-mechanical bowel preparation in combination with OAB, second group-mechanical bowel preparation alone, and third group-no preparation.

There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups of bowel preparation in terms of reoperation for anastomotic leak management.

The implementation of mechanical bowel preparation and antibiotic use in patients who are going to undergo a colon resection does not influence the treatment of any possible anastomotic leakage.

With the findings of this study we think that the clinical decision on the further treatment of anastomotic leak should not be influenced by the patient’s preoperative bowel preparation.

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the hospitals participating in the ACS NSQIP are the source of the data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

| 1. | Walker KG, Bell SW, Rickard MJ, Mehanna D, Dent OF, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Anastomotic leakage is predictive of diminished survival after potentially curative resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2004;240:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kingham TP, Pachter HL. Colonic anastomotic leak: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:269-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Scarborough JE, Mantyh CR, Sun Z, Migaly J. Combined Mechanical and Oral Antibiotic Bowel Preparation Reduces Incisional Surgical Site Infection and Anastomotic Leak Rates After Elective Colorectal Resection: An Analysis of Colectomy-Targeted ACS NSQIP. Ann Surg. 2015;262:331-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shogan BD, Carlisle EM, Alverdy JC, Umanskiy K. Do we really know why colorectal anastomoses leak? J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1698-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Contant CM, Hop WC, van't Sant HP, Oostvogel HJ, Smeets HJ, Stassen LP, Neijenhuis PA, Idenburg FJ, Dijkhuis CM, Heres P, van Tets WF, Gerritsen JJ, Weidema WF. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370:2112-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Grosso G, Biondi A, Marventano S, Mistretta A, Calabrese G, Basile F. Major postoperative complications and survival for colon cancer elderly patients. BMC Surg. 2012;12 Suppl 1:S20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jung B, Påhlman L, Nyström PO, Nilsson E; Mechanical Bowel Preparation Study Group. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94:689-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Poth EJ, Knotts FL. Clinical Use of Succinylsulfathiazole. Arch Surg. 1942;44; 208-222. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nichols RL, Condon RE. Preoperative preparation of the colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132:323-337. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Fenech DS, McLeod RS; Best Practice in General Surgery Committee. Preoperative bowel preparation for patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery: a clinical practice guideline endorsed by the Canadian Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Can J Surg. 2010;53:385-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kiran RP, Murray AC, Chiuzan C, Estrada D, Forde K. Combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics significantly reduces surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, and ileus after colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262:416-25; discussion 423-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, Hur K, Demakis J, Aust JB, Chong V, Fabri PJ, Gibbs JO, Grover F, Hammermeister K, Irvin G, McDonald G, Passaro E, Phillips L, Scamman F, Spencer J, Stremple JF. The Department of Veterans Affairs' NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 1998;228:491-507. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bucher P, Gervaz P, Egger JF, Soravia C, Morel P. Morphologic alterations associated with mechanical bowel preparation before elective colorectal surgery: a randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:109-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ayus JC, Levine R, Arieff AI. Fatal dysnatraemia caused by elective colonoscopy. BMJ. 2003;326:382-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hookey LC, Depew WT, Vanner S. The safety profile of oral sodium phosphate for colonic cleansing before colonoscopy in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:895-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mackey AC, Shaffer D, Prizont R. Seizure associated with the use of visicol for colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2095; author reply 2095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hayakawa Y, Tanaka Y, Funahashi H, Imai T, Matsuura N, Oiwa M, Kikumori T, Mase T, Tominaga Y, Nakao A. Hyperphosphatemia accelerates parathyroid cell proliferation and parathyroid hormone secretion in severe secondary parathyroid hyperplasia. Endocr J. 1999;46:681-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Biondi A, Langdon S S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ