©The Author(s) 2019.

World J Gastrointest Surg. Feb 27, 2019; 11(2): 62-84

Published online Feb 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62

Published online Feb 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62

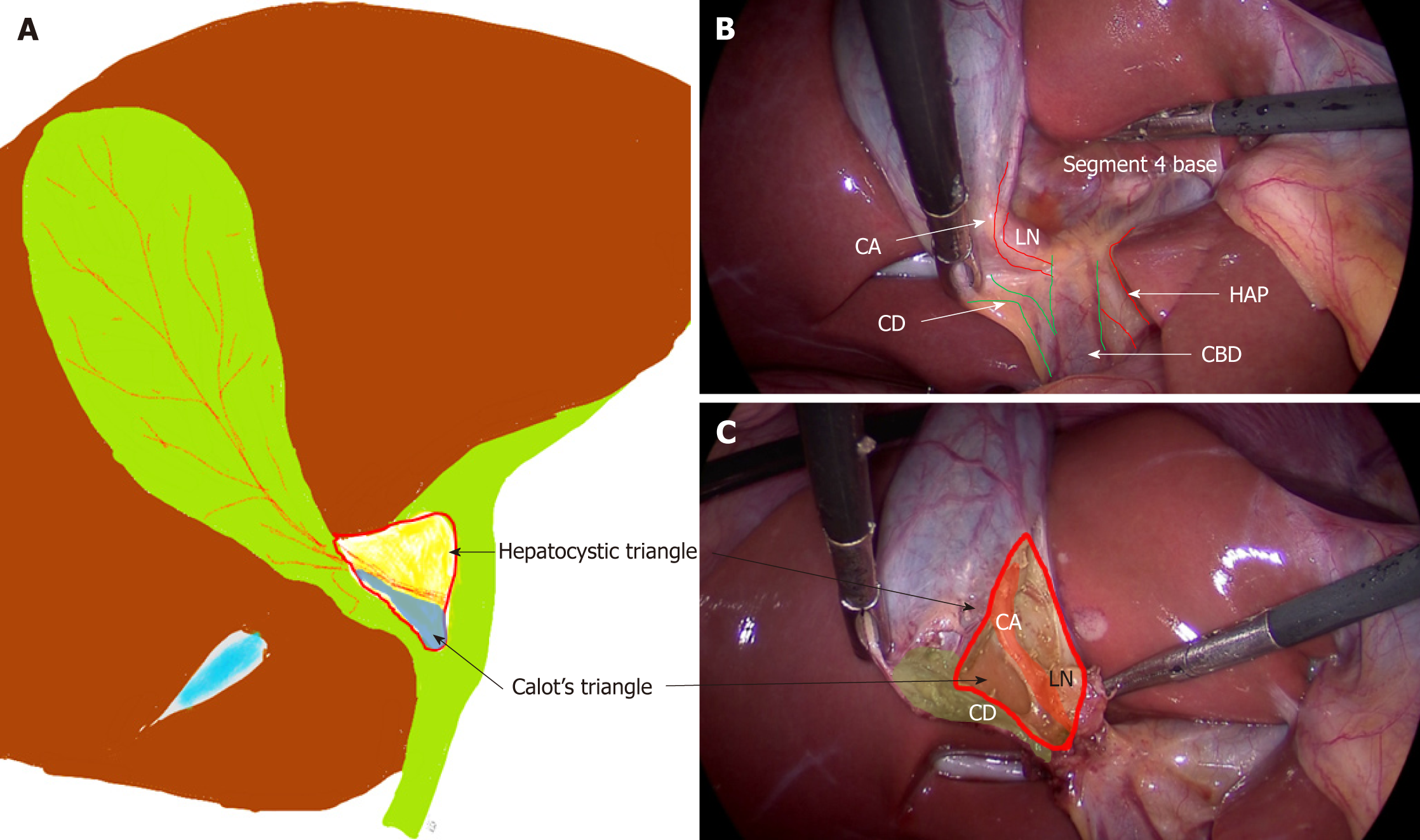

Figure 1 Anatomy of hepatocystic and Calot’s triangles.

A: Hepatocystic triangle (red outline); Calot’s triangle (in blue); Relevant anatomical structures; B: Before dissection; C: After dissection. CD: Cystic duct; CA: Cystic artery; LN: Lymph node; HAP: Hepatic artery proper; CBD: Common bile duct.

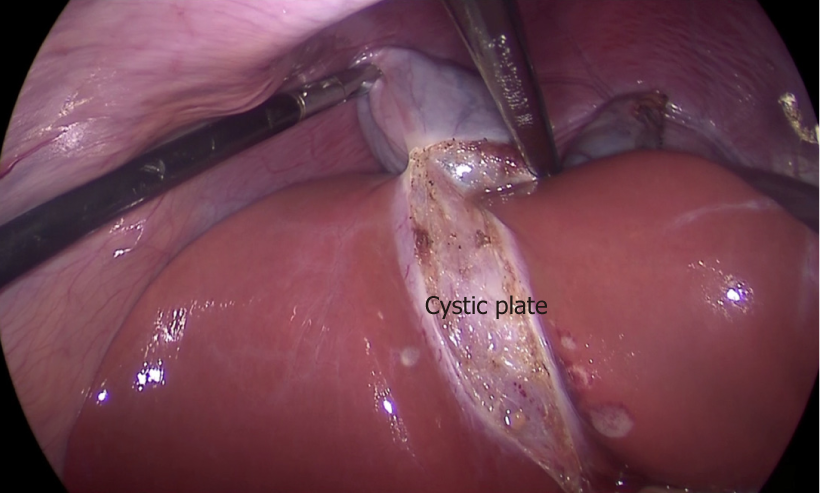

Figure 2 Cystic plate is visualized after the gallbladder is dissected off its liver bed.

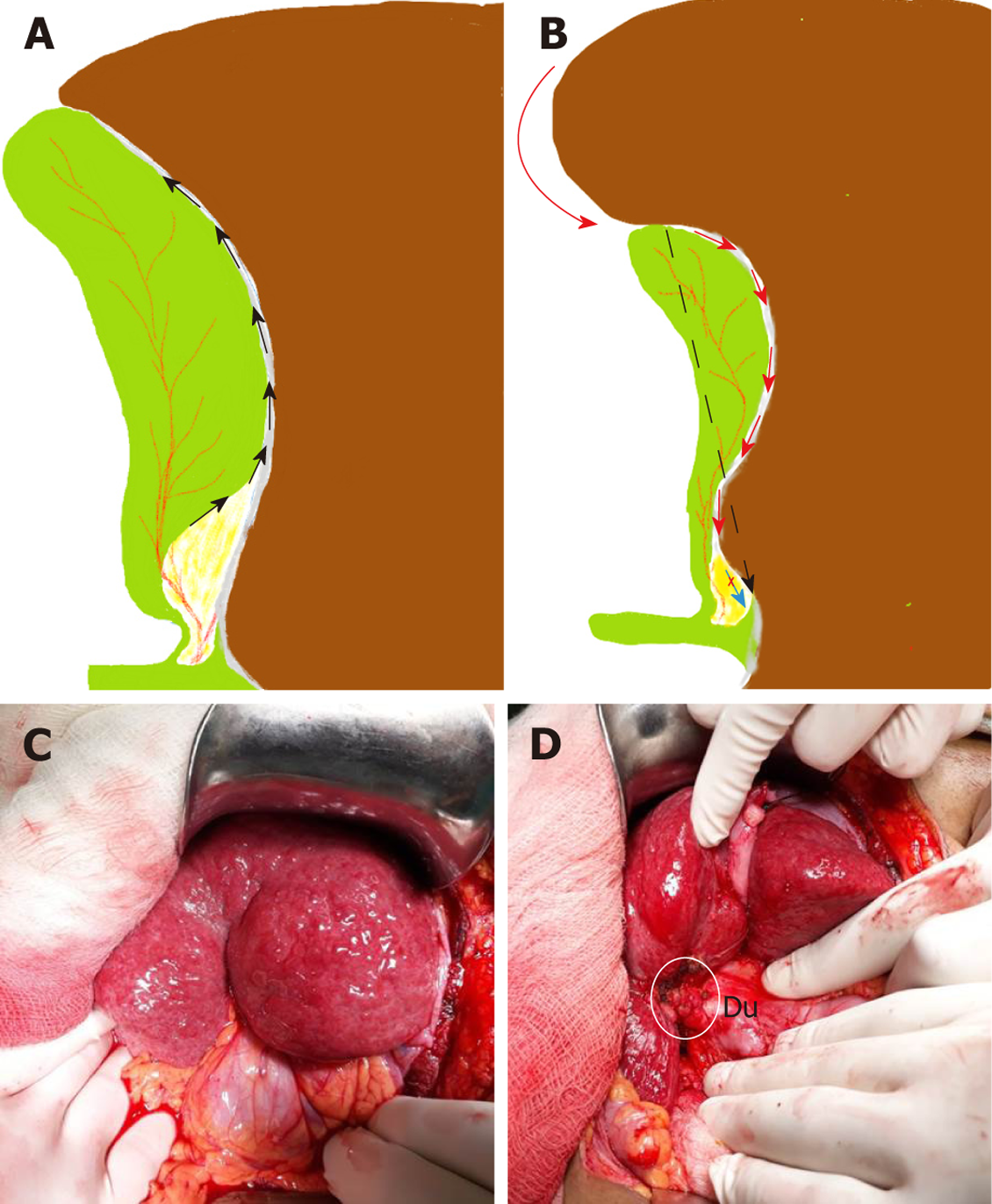

Figure 3 Understanding surgical planes during dissection.

A: Usually, in uncomplicated cases, plane of dissection remains close to the gallbladder that leaves behind the cystic plate attached to liver; B: In chronic cholecystitis, with small shrunken gallbladder, liver puckering develops (red curved arrow) with shortening of the cystic plate (black interrupted arrow). With loss of plane, the surgeon tends to breach the cystic plate (red arrows) resulting in bleeding from the liver. In addition, there is a risk to enter in to the right portal pedicle during fundus first approach (blue arrow) if such danger is not appreciated; C: Pucker sign as noted during open cholecystectomy; D: Small contracted scarred gallbladder (in white circle) was identified after separating adherent omentum and colon. Duodenum (Du) was densely adherent to the gallbladder. Findings such as in C and D suggest difficult cholecystectomy.

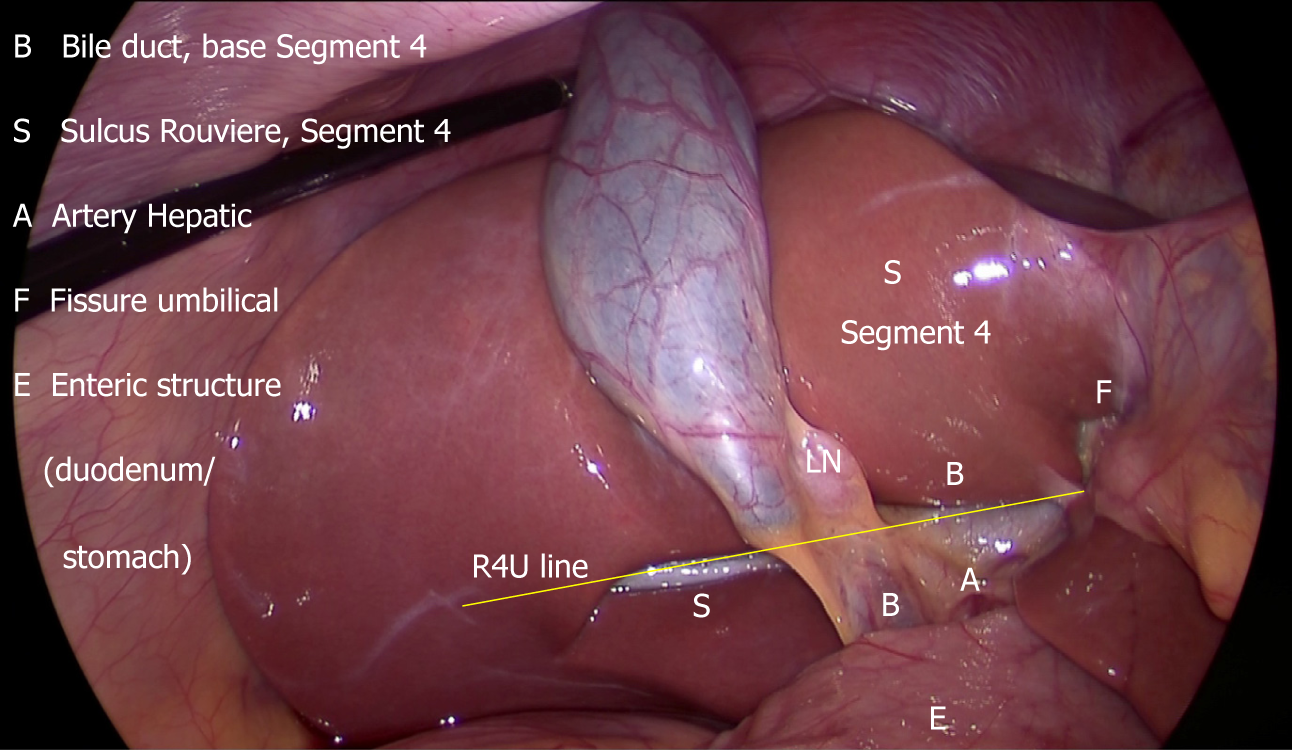

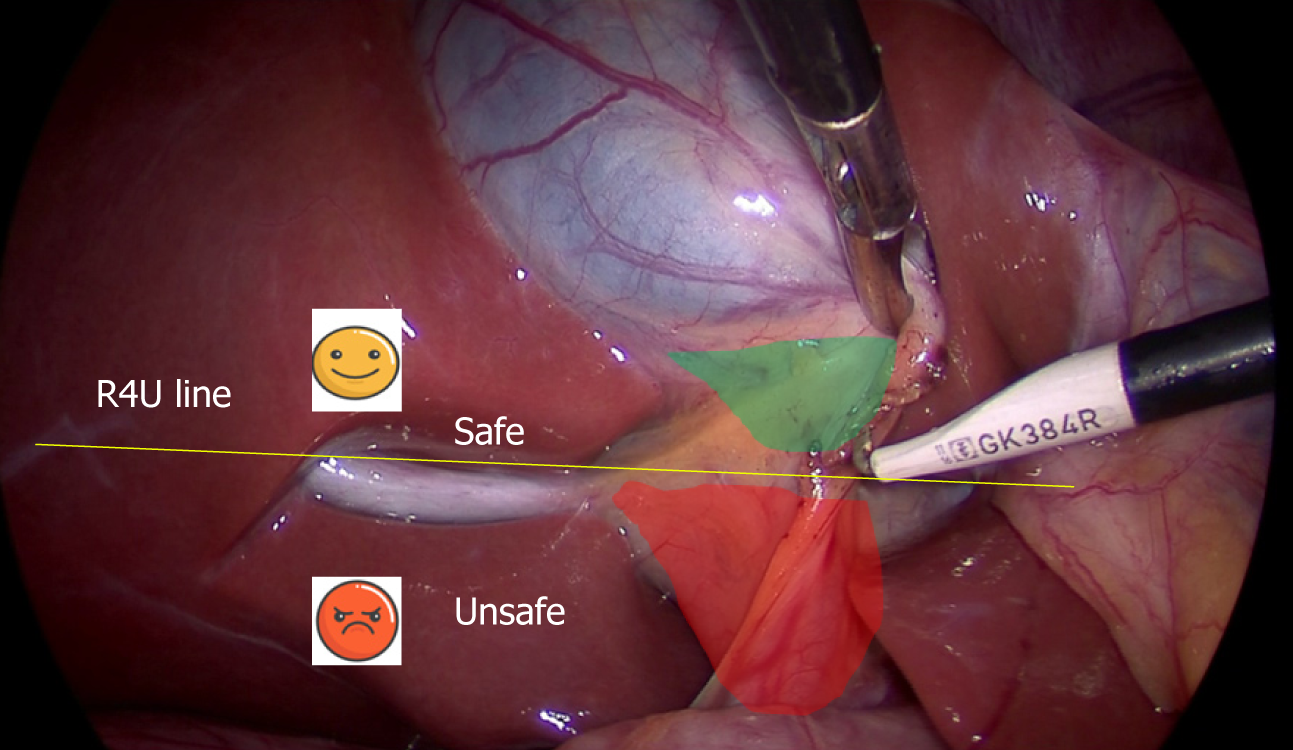

Figure 4 B-SAFE anatomical landmarks and R4U safety line.

If Rouviere’s sulcus is not present, then the imaginary line passing across the base of the segment 4 from the umbilical fissure may be extended towards right across the hepatoduodenal ligament to ascertain safe zone of dissection (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Surgical field of interest during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

It is important to identify safe (green) and danger (red) zones of dissection as demarcated by R4U line.

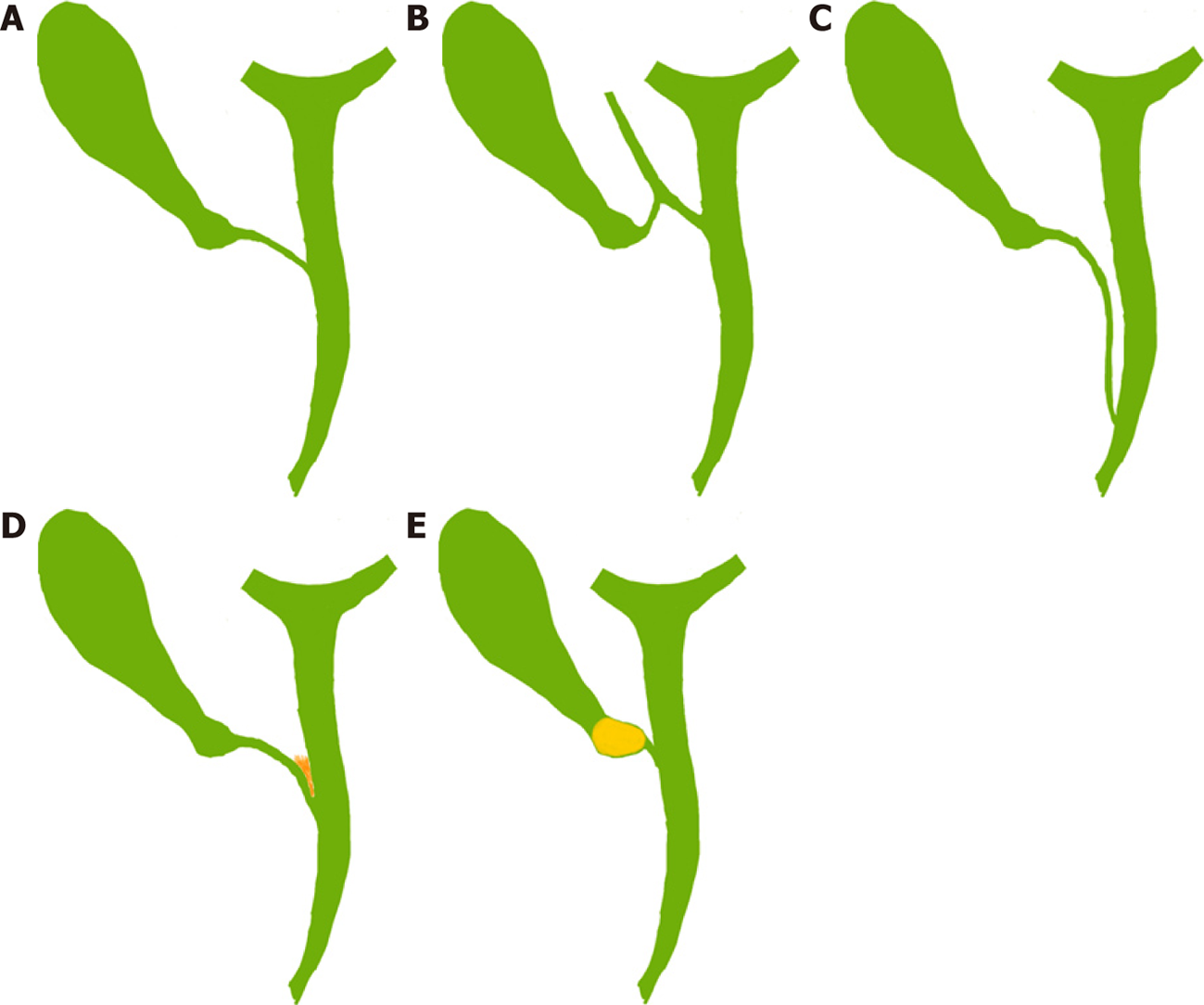

Figure 6 Cystic ductal variations, anatomical and pathological.

A: Normal pattern with angular insertion; B: Cystic duct insertion in aberrant right hepatic (sectional) duct; C: Cystic duct - parallel course. Cystic duct may be quiet long and may join the common hepatic duct (CHD) near ampulla; D: Cystic ductal fusion with the CHD due to inflammation; E: Short/effaced cystic duct due to impacted stone in the gallbladder neck. In both situations (D and E), CHD would be at risk of injury during dissection especially when the surgeon tries to expose the cystic duct-common bile duct junction.

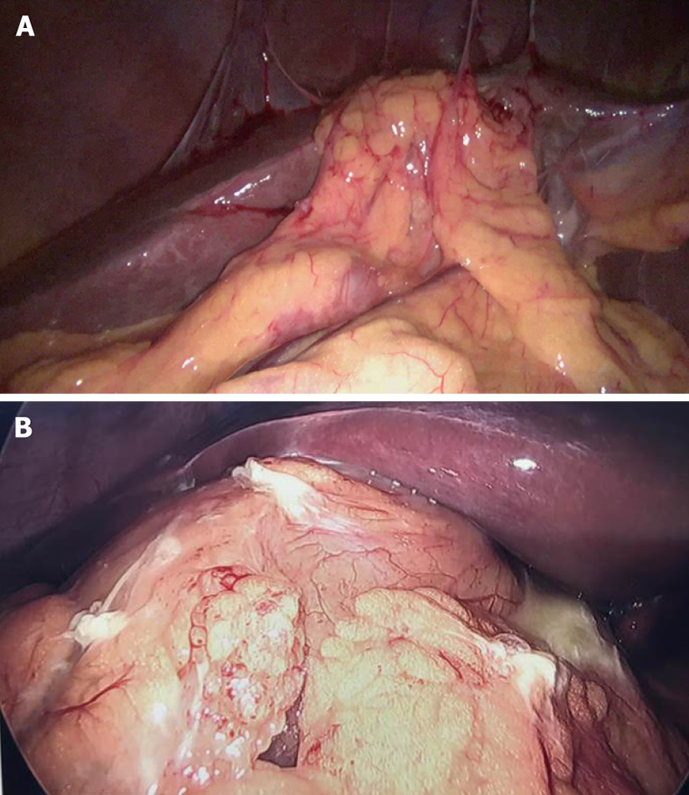

Figure 7 Example of intraoperative prediction of difficult gallbladder.

A: Moderate pericholecystic adhesions; B: Extensive pericholecystic adhesion. Gallbladder is not visualized in both of these situations predicting difficult dissection. Such findings may suggest severe underlying inflammation with or without the presence of contained gallbladder perforation or cholecystoenteric fistula. The surgeon should be careful during dissection as adjoining adherent viscera, duodenum or colon, might be injured during adhesiolysis.

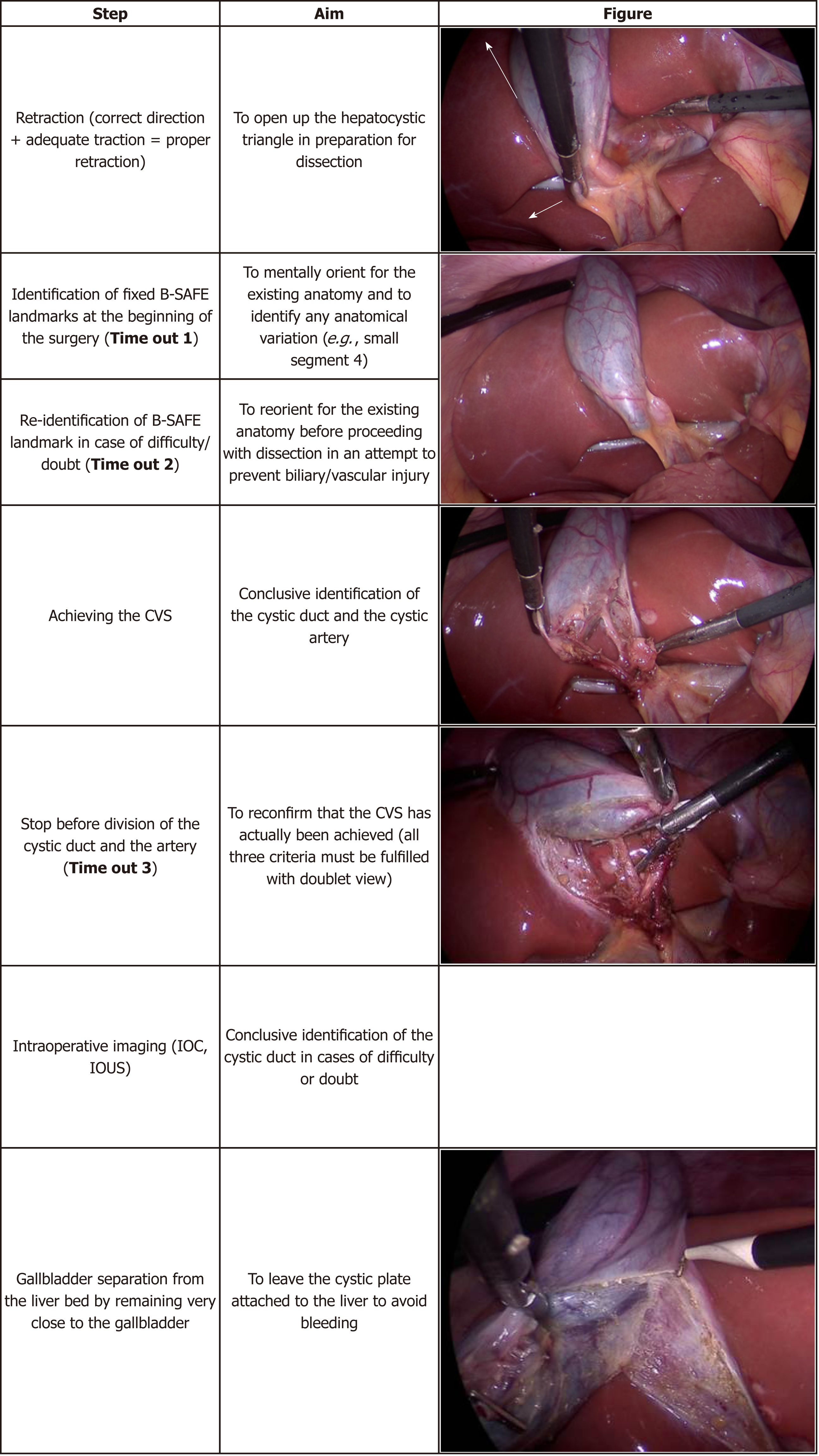

Figure 8 Important steps during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CVS: Critical view of safety; IOC: Intraoperative cholangiography; IOUS: Intraoperative ultrasonography.

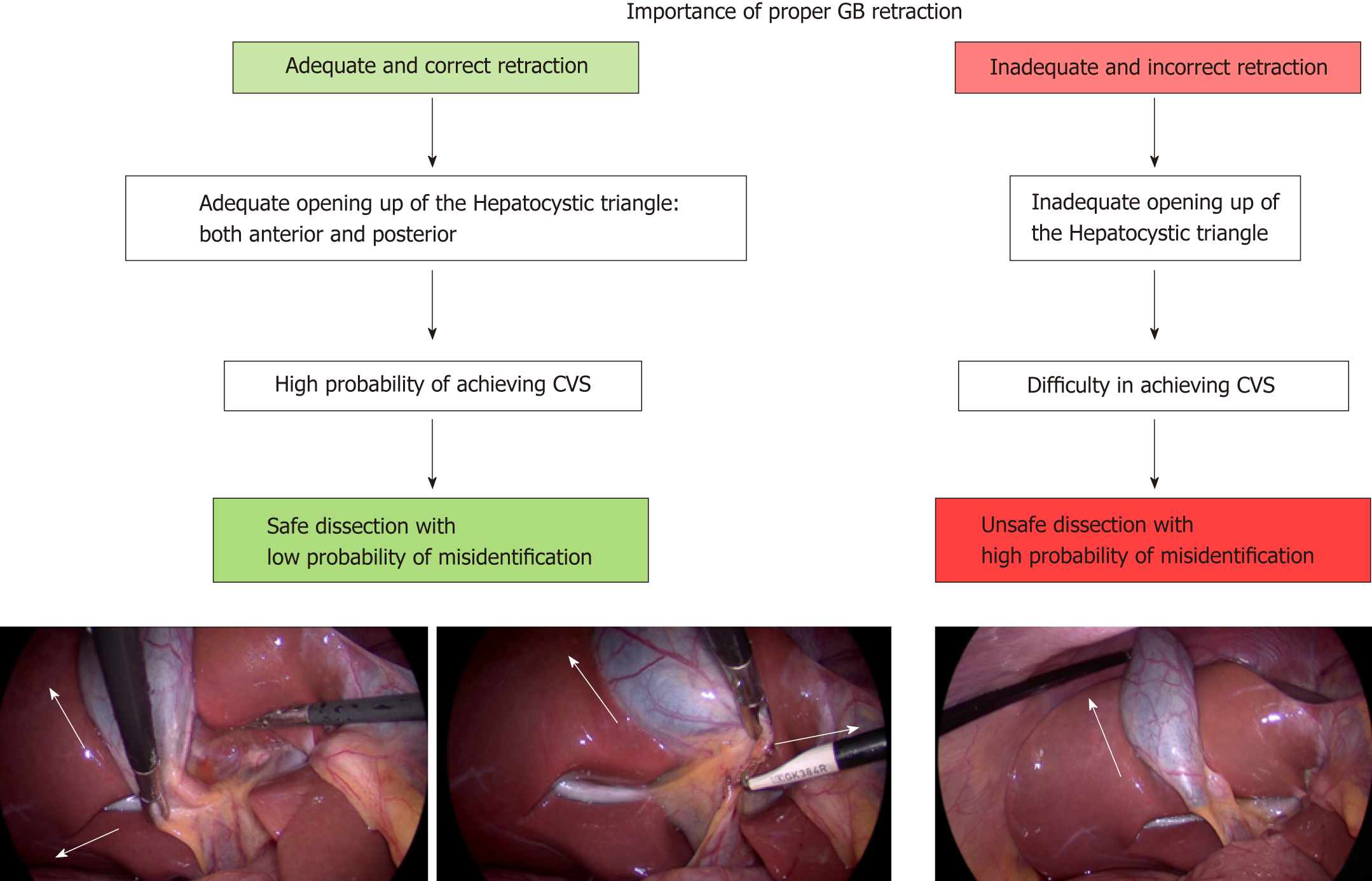

Figure 9 Importance of proper retraction of gallbladder during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Proper retraction of fundus towards right shoulder of the patient (arrow) and right inferolateral retraction of neck (arrow) allows adequate exposure of hepatocystic triangle. Fundal retraction only is inadequate as it aligns common bile duct with cystic duct with a risk of misidentification. CVS: Critical view of safety; GB: Gallbladder.

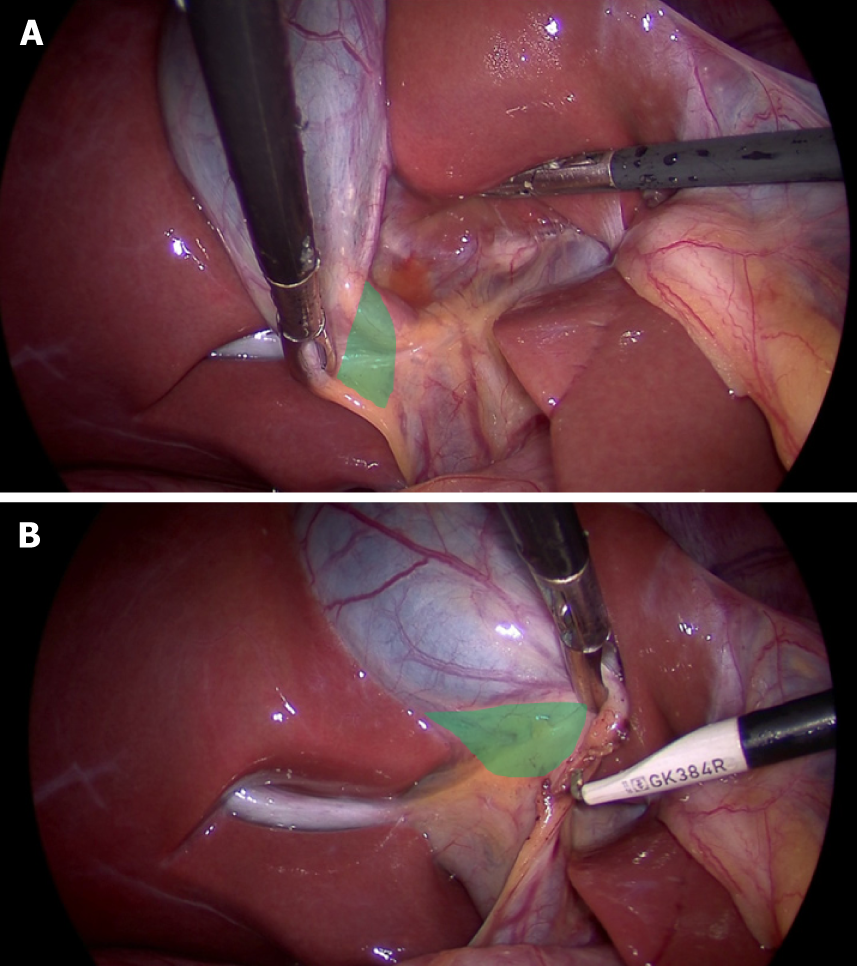

Figure 10 Proper retraction of infundibulum (neck) allows.

A: Exposure of anterior aspect of hepatocystic (HC) triangle when infundibulum is retracted in right inferolateral direction; B: Exposure of posterior aspect of HC triangle when infundibulum is retracted towards umbilical fissure.

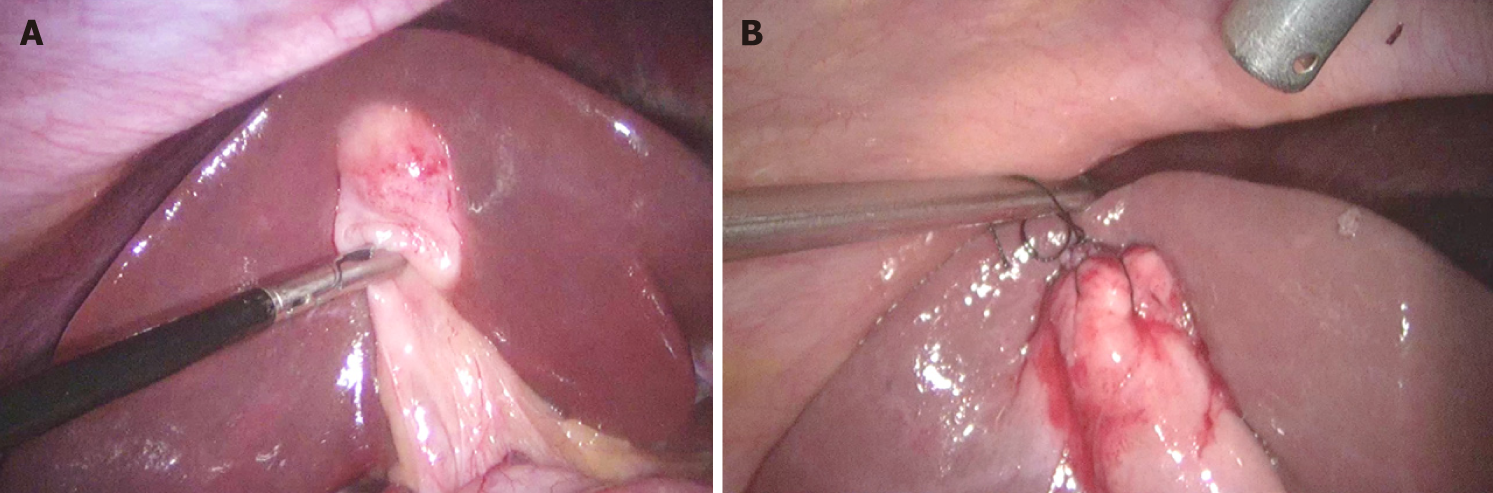

Figure 11 Useful manoeuvre for gallbladder retraction.

A: Very thick fundus and impacted stone in the fundus make grasping and retraction difficult; B: Retraction can be facilitated by taking stay sutures. However, gallbladder penetration/perforation must be avoided during retraction if there is any suspicion of gallbladder malignancy.

Figure 12 Flowchart showing overall scheme of performance of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the culture of safety concept.

GB: Gallbladder; B-SAFE: Surgical landmarks; HC triangle: Hepatocystic triangle; CVS: Critical view of safety.

Figure 13 Critical view of safety with all three components: (1) Fibrofatty tissue has been cleared from the hepatocystic triangle; (2) Lower part of the cystic plate has been clearly exposed; and (3) Only two tubular structures are seen entering the gallbladder.

A: Anterior view; B: Posterior view (inverted hepatocystic triangle).

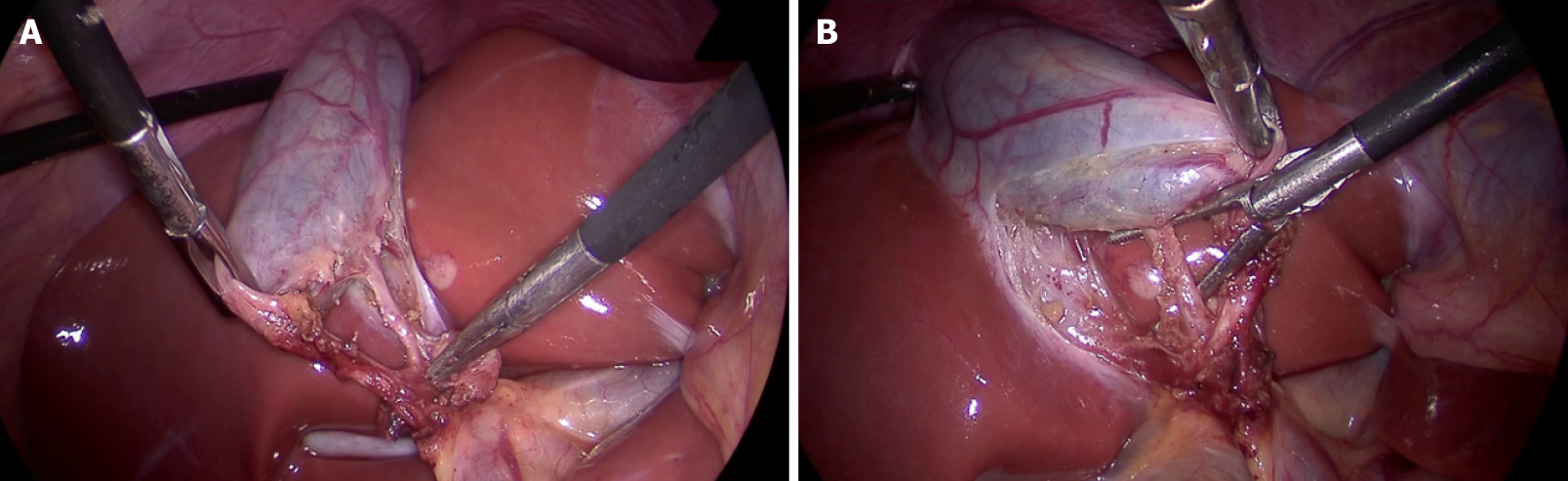

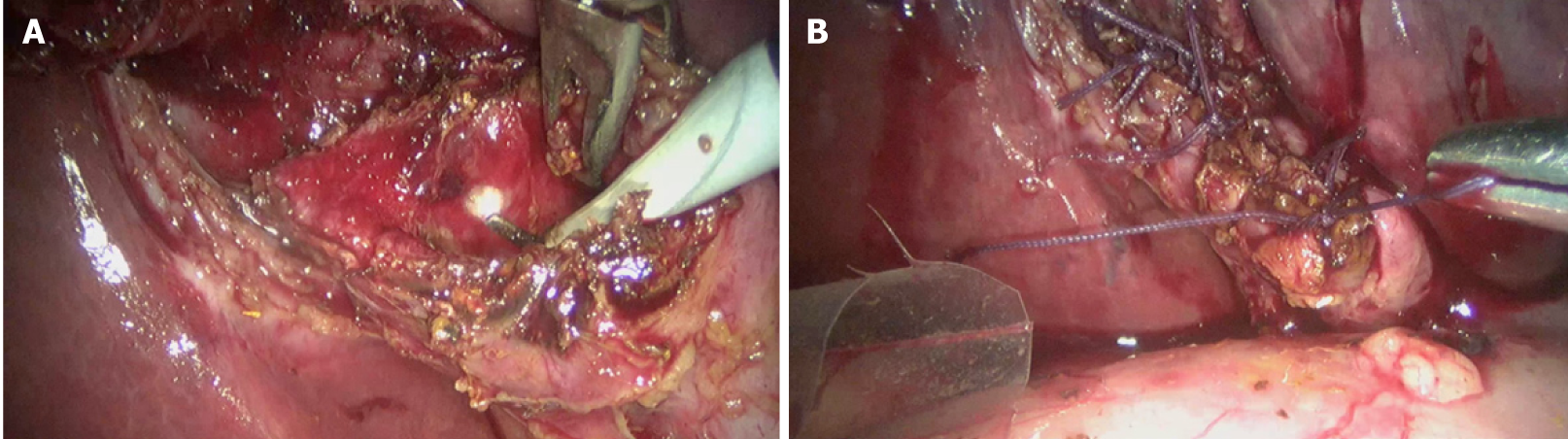

Figure 14 Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy (reconstituting) as a bailout procedure.

A: Mucosa of the gallbladder stump is fulgurated after removal of as much gallbladder as safely possible; B: Stump is closed after ensuring no stone is left behind in this stump.

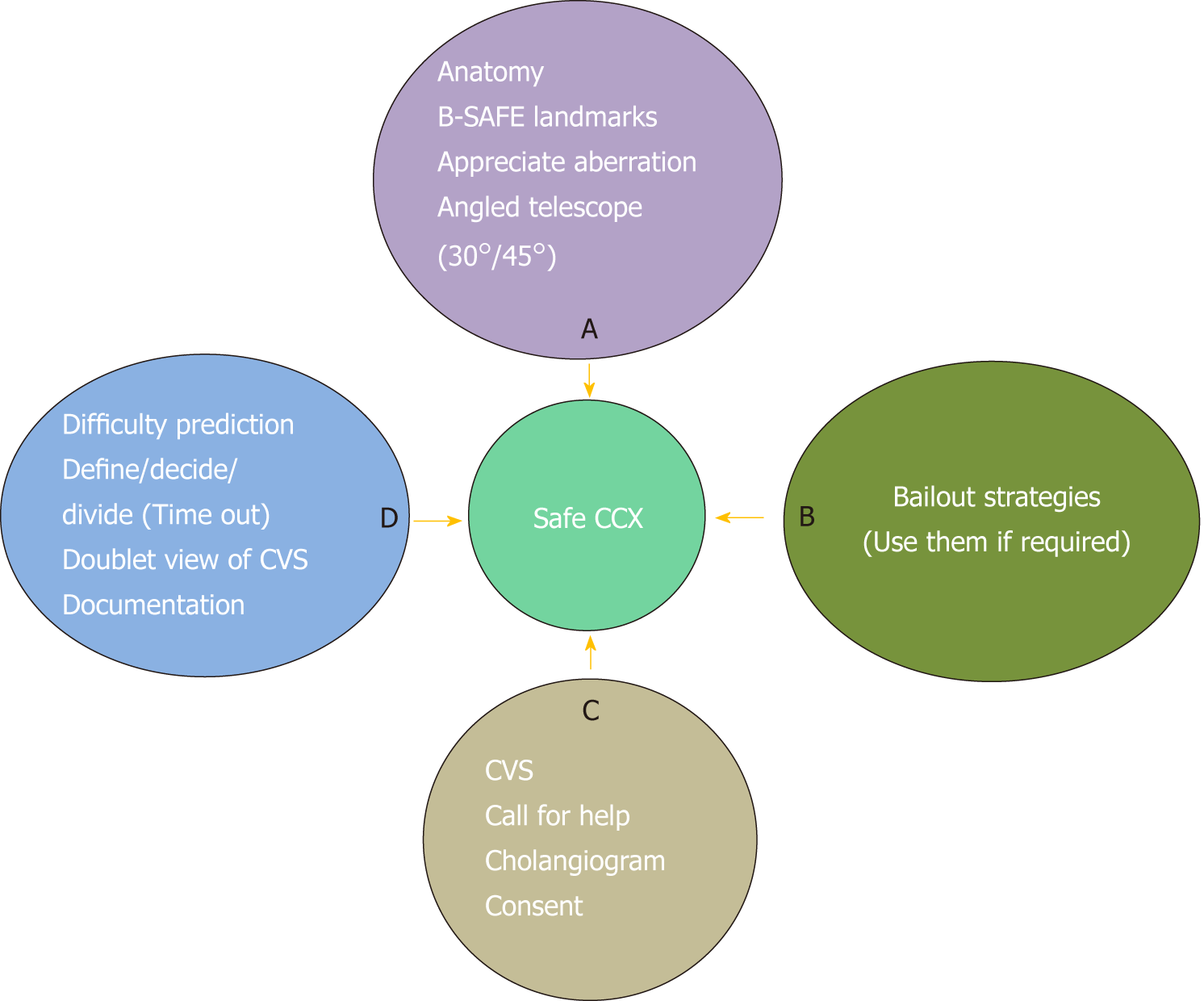

Figure 15 “ABCD” of safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

CVS: Critical view of safety; CCX: Cholecystectomy.

- Citation: Gupta V, Jain G. Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World J Gastrointest Surg 2019; 11(2): 62-84

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i2/62.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i2.62