Published online Apr 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.189

Peer-review started: October 7, 2016

First decision: December 13, 2016

Revised: December 25, 2016

Accepted: February 8, 2017

Article in press: February 13, 2017

Published online: April 16, 2017

Processing time: 190 Days and 3.9 Hours

To determine the risk factors of severe post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (sPEP) and clarify the indication of prophylactic treatments.

At our hospital, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed on 1507 patients from May 2012 to December 2015. Of these patients, we enrolled all 121 patients that were diagnosed with post endoscopic retrograde PEP. Fourteen of 121 patients diagnosed as sPEP were analyzed.

Forty-one patients had contrast media remaining in the pancreatic duct after completion of ERCP. Seventy-one patients had abdominal pain within three hours after ERCP. These were significant differences for sPEP (P < 0.05). The median of Body mass index, the median time for ERCP, the median serum amylase level of the next day, past histories including drinking and smoking, past history of pancreatitis, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction, whether emergency or not, expertise of ERCP procedure, diverticulum nearby Vater papilla, whether there was sphincterotomy or papillary balloon dilation, pancreatic duct cannulation, use of intra-ductal ultrasonography enforcement, and transpapillary biopsies had no significant differences with sPEP.

Contrast media remaining in the pancreatic duct and the appearance of abdominal pain within three hours after ERCP were risk factors of sPEP.

Core tip: Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) is a typical endoscopy-related accident in the biliopancreatic field. Since PEP is a predictable pathology, and if discovered and appropriately treated early many patients rapidly recover. However, some cases aggravate to a severe state and become fatal. Therefore, it is important to identify factors leading PEP to a severe state. In our study, significant differences were noted in residual enhancement of the pancreatic duct and development of abdominal pain showing that these were independent risk factors of severe PEP. The presence of these findings is an indication of therapeutic intervention for severe PEP.

- Citation: Matsubara H, Urano F, Kinoshita Y, Okamura S, Kawashima H, Goto H, Hirooka Y. Analysis of the risk factors for severity in post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: The indication of prophylactic treatments. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(4): 189-195

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i4/189.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.189

Post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) is a typical endoscopy-related accident in the biliopancreatic field, and there are many reports on its risk factors[1-4]. Many researchers reported methods to prevent PEP[5-17]. However, treatment to prevent PEP in all endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) patients is not recommended in consideration of accidents caused by the addition of preventive techniques, adverse reactions of preventive drug administration, and cost[13]. Since PEP is a predictable pathology, and if discovered and appropriately treated early many patients rapidly recover. However, some cases aggravate to a severe state and become fatal. Therefore, it is important to identify factors leading PEP to a severe state, and when such risk factors are observed, therapeutic intervention, such as the addition of preventive techniques and preventive drug administration, should be performed. The objective of this study was to retrospectively clarify risk factors aggravating PEP to a severe state and determine the indications to prevent and treat PEP.

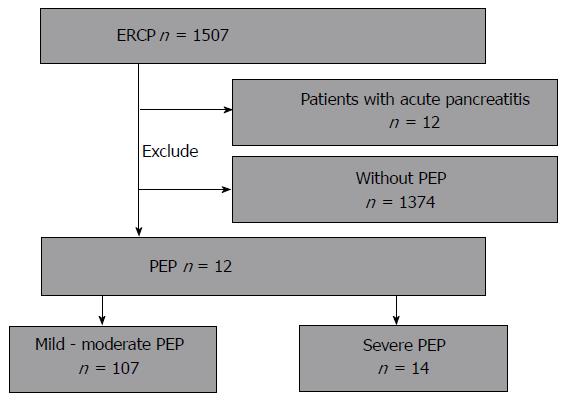

Between May 2012 and October 2015, 1507 patients were examined by ERCP at our hospital. PEP was diagnosed in 121 of them (8.02%), and 14 of them were diagnosed with severe PEP (sPEP) and analyzed. Patients accompanied by acute pancreatitis at the time of undergoing ERCP were excluded (Figure 1). The study was performed in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki and registered at UMIN-CTR (000022086).

For ERCP, a side-view duodenoscope was used. The endoscope used was JF260V (Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan). For the cannula, for contrast medium, a 0.035-inch V system (Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used. For the guide wire, Jagwire (0.035inch; Boston scientific Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) or Visigride (0.025 inch; Olympus Medical, Tokyo, Japan) was used. Replacement fluid (2000 mL) was intravenously administered within 24 h before and after ERCP. Patients received protease inhibitor (nafamostat mesilate, 20 mg/d) and prophylactic antibiotic administration (sulbactam/cefoperazone, 2 g/d) for 2 d. Vitals were checked 3 h after completion of ERCP. For patients in whom abdominal pain developed before this, 25 or 50 mg of indomethacin suppositories were administered. When PEP was diagnosed, sufficient fluid replacement including protease inhibitor and antibiotics was continued so as to maintain the urinary volume at 1 mL/min under monitoring of circulatory dynamics.

PEP was diagnosed following the Cotton’s criteria[16]: When abdominal pain developed on the day following ERCP and the serum amylase level was 3 times or higher than the normal upper limit, the patient was diagnosed with PEP. sPEP was defined as PEP with 10 d or longer prolongation of inpatient treatment, hemorrhagic pancreatitis, phlegmon, and pseudocyst.

Clinical data of PEP patients were retrospectively extracted from their clinical records. As sPEP risk factors, age, gender, Body mass index (BMI), past medial history including cigarette smoking and alcohol drinking and acute pancreatitis, the presence or absence of the sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), diverticulum nearby Vater papilla and common bile duct (CBD) diameter of patient with CBD stones, whether or not it was emergency ERCP, whether or not EST or EPBD was performed, pancreatography, the presence or absence of residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct after completion of ERCP, the use of IDUS and transpapillary biopsy, treatment time, experience of operators, development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP, and serum amylase level, white blood cell count, and C-reactive protein on the day following ERCP were surveyed (Tables 1 and 2). The time from insertion to removal of a scope was defined as the ERCP treatment time. Experience of operators was defined based on the total and recent numbers of ERCP performed. Operators with a total number of ERCP performed of 200 or fewer and/or a recent number of ERCP performed of 40 or fewer per year were regarded as non-expert. Unfortunately, no study has examined role of sphincterotomy and number of pancreatic cannulation except our following conference paper.

| Variables | Mild-moderate PEP | Severe PEP |

| Age (yr) (n = 121) | ||

| Median | 73.7 | 76.5 |

| (range) | (18-93) | (32-88) |

| Gender (n = 121) | ||

| Male/female | 57/50 | 7/7 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (n = 121) | ||

| Median | 21.6 | 23.2 |

| (range) | (13.97-35.20) | (14.79-29.5) |

| Smoking status (n = 121) | ||

| Non-smoker/Ex- or current smoker | 83/24 | 7/7 |

| Drinking status (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 67/40 | 12/2 |

| Past history (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 31/76 | 4/10 |

| Malignant disease (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 84/23 | 10/4 |

| History of pancreatitis (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 106/1 | 1/13 |

| SOD (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 101/6 | 1/13 |

| Diverticulum nearby vater papilla (n = 121) | ||

| Absent/present | 70/37 | 11/3 |

| CBD diameter of patient with CBD stones (n = 41) | ||

| ≥ 10 mm/< 10 mm | 21/16 | 2/2 |

| Variables | Mild-moderate PEP (n = 107) | Severe PEP (n = 14) |

| ERCP procedure | ||

| Not emergency/emergency | 91/16 | 13/1 |

| EST | 29 | 2 |

| EPBD | 12 | 2 |

| Pancreatography | ||

| No/yes | 38/69 | 9/5 |

| Contrast media remained in the pancreatic duct | ||

| No/yes | 75/32 | 5/9 |

| IDUS | ||

| No/yes | 86/21 | 9/5 |

| Transpapillary biopsies | ||

| No/yes | 76/31 | 10/4 |

| Time for ERCP procedure (min) | ||

| Median | 50 | 56 |

| (range) | (12-170) | (26-150) |

| Expertise of ERCP procedure | ||

| Not expert/expert | 62/45 | 9/5 |

| Abdominal pain within three hours after ERCP | ||

| No/yes | 49/58 | 1/13 |

| Serum amylase level of the next day (IU/mL) | ||

| Median | 1001 | 1543 |

| (range) | (83-3604) | (258-2969) |

| White blood cell of the next day (/μL) | ||

| median | 8040 | 8790 |

| (range) | (3240-26320) | (6270-13410) |

| C-reactive protein of the next day (mg/dL) | ||

| Median | 2.08 | 3.1 |

| (range) | (0.04-32.55) | (0.20-38.31) |

In the univariate analysis, the difference between the two groups of categorical parameters were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 test. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for continuous parameters. The stepwise logistic regression model (forward selection) was used to calculate the odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI. Significant predictors in the univariate analysis were then included in a forward stepwise multiple logistic regression model. All tests were two-sided and P values of < 0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistical software (version 21; SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan).

The median age of the 121 PEP patients was 76 (18-91) years old, and there were 64 male (52.9%) and 57 female (47.1%) patients. The median BMI was 21.2 (14.0-35.2) kg/m2. Thirty-one and 42 patients were cigarette smokers and habitual alcohol drinkers, respectively. The past medical history was heart disease in 21 patients, diabetes in 24, chronic kidney disease in 41, malignant disease in 27, and acute pancreatitis in 2. SOD was suspected in 7. Diverticulum nearby Vater papilla was noted in 40. Forty-one patients had CBD stones (Table 3).

| Variables | No. of patients | Median of patients (range) | Univariate analysis P value |

| Age (yr) (n = 121) | 76 (18-91) | 0.874 | |

| Gender (n = 121) | 0.818 | ||

| Male/female | 64/57 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) (n = 121) | 21.2 (14.0-35.2) | 0.379 | |

| Smoking status (n = 121) | 0.201 | ||

| Non-smoker/Ex- or current smoker | 90/31 | ||

| Drinking status (n = 121) | 0.302 | ||

| Absent/present | 79/42 | ||

| Past history (n = 121) | 0.967 | ||

| Absent/present | 35/86 | ||

| Malignant disease (n = 121) | 0.550 | ||

| Absent/present | 94/27 | ||

| History of pancreatitis (n = 121) | 0.606 | ||

| Absent/present | 119/7 | ||

| SOD (n = 121) | 0.644 | ||

| Absent/present | 114/7 | ||

| Diverticulum nearby vater papilla (n = 121) | 0.325 | ||

| Absent/present | 81/40 | ||

| CBD diameter of patient with CBD stones (n = 41) | 0.796 | ||

| ≥ 10 mm/< 10 mm | 23/18 |

ERCP was performed urgently in 17 patients. EST and EPBD were performed in 31 and 14 patients, respectively. Pancreatography was performed in 74 patients, and residual enhancement of the pancreatic duct was noted at completion of ERCP in 41 patients. IDUS and transpalillary biopsy were performed in 26 and 35 patients, respectively. The median treatment time was 50 (12-170) min. Experts and non-experts performed ERCP in 50 and 71 patients, respectively. Abdominal pain developed within 3 h after completion of ERCP in 71 patients. The median serum amylase level, WBC count, and serum CRP on the day following ERCP were 1065 (83-3604) IU/mL, 8050 (3240-26320)/μL, and 2.1 (0.04-38.31) mg/dL, respectively (Table 4). No patients died during the study.

| Variables | No. of patients (n = 121) | Median of patients (range) | Univariate analysis P value |

| ERCP procedure | 0.429 | ||

| Not emergency/emergency | 104/17 | ||

| EST | 31 | 0.302 | |

| EPBD | 14 | 0.736 | |

| Pancreatography | 0.798 | ||

| No/yes | 47/74 | ||

| Contrast media remained in the pancreatic duct | 0.011 | ||

| No/yes | 80/41 | ||

| IDUS | 0.168 | ||

| No/yes | 95/26 | ||

| Transpapillary biopsies | 0.975 | ||

| No/yes | 86/35 | ||

| Time for ERCP procedure (min) | 50 (12-170) | 0.343 | |

| Expertise of ERCP procedure | 0.65 | ||

| Not expert/expert | 71/50 | ||

| Abdominal pain within three hours after ERCP | 0.006 | ||

| No/yes | 50/51 | ||

| Serum amylase level of the next day (IU/mL) | 1065 (83-3604) | 0.184 | |

| White blood cell of the next day (/μL) | 8050 (3240-26320) | 0.668 | |

| C-reactive protein of the next day (mg/dL) | 2.1 (0.04-38.31) | 0.601 |

On univariate analysis, residual enhancement of the pancreatic duct at completion of ERCP and development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP were significant risk factors of sPEP (Tables 3 and 4). On multivariate analysis, significant differences were noted in residual enhancement of the pancreatic duct (OR = 4.254, 95%CI: 1.238-14.616) and development of abdominal pain (OR = 11.881, 95%CI: 1.400-100.784), showing that these were independent risk factors of sPEP (Table 5).

| Variables | Multivariate analysis | |

| Odds ratio (95%CI) | P value | |

| Contrast media remained in the pancreatic duct | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 4.254 (1.238-14.616) | 0.021 |

| Abdominal pain within three hours after ERCP | ||

| No | 1 | |

| Yes | 11.881 (1.400-100.784) | 0.023 |

It has been reported that the incidence of PEP in all patients examined by ERCP was about 3.5%, and PEP aggravated to a severe state (sPEP) in 0.4%[17]. Therefore, the indication of ERCP should be carefully judged. It has become possible to refrain from performing diagnostic ERCP as low-invasive examination techniques, such as MDCT, MRI, and EUS, have improved. However, ERCP is still essential as a therapeutic measure to diagnose the advancement of biliary tract malignancy and obstructive disease of the pacreaticobiliary duct, and ERCP has to be inevitably performed although there is a risk of causing PEP. There are many previous reports on risk factors of PEP, but risk factors of sPEP are unclear. Generally admitted risk factors of PEP include female gender, pancreatic sphincterotomy, difficulty in cannulation, 3 times or more applications of ERP, ERP reaching the tail of the pancreas even if it was performed once, excess contrast pressure, contrast imaging of the pancreatic acinus, brushing pancreatic juice cytology, and SOD[1-4]. These were risk factors of PEP, but not risk factors of sPEP in our study.

In our study, the residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct at completion of ERCP was an independent risk factor of sPEP, suggesting that reduction of intraductal pressure of the pancreas at completion of ERCP may prevent sPEP, which may lead to a method to effectively avoid sPEP. Akashi et al[5] compared groups with and without the addition of EST and observed that the incidence of sPEP was lower in the group with EST. They hypothesized that reduction of intraductal pressure of the pancreas by the addition of EST reduced the incidence of sPEP. However, EST may accidentally perforate the digestive tract and it is contraindicated for patients treated with oral antithrombin. Thus, not all patients should be treated with EST. On the other hand, Nakahara et al[6] reported that when the pancreatic duct guide wire method is employed for a patient with difficult bile duct cannulation, pancreatic duct stenting should be performed even though EST was added. In addition, Ito et al[7] reported that preventive pancreatic duct stenting contributes to reducing the incidence of PEP, excluding IPMN patients not accompanied by pancreatic duct dilatation in the pancreatic head. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline[18] and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Guideline[19] recommend pancreatic duct stenting in patients with a risk factor, and Sofuni et al[8] reported that the use of a spontaneous dislodgment pancreatic duct stent prevented PEP regardless of the presence or absence of a risk factor. However, the frequency of cannulation for stenting increases as a problem with preventive pancreatic duct stenting. We also consider that pancreatic duct stenting reported by many researchers[6-12,15], is an effective method to prevent PEP including sPEP, but no patients with pancreatic duct stenting were included in our study. The appropriate conditions for pancreatic duct stenting in ERCP patients have not been established, but, based on the results of our study, conduct of a large-scale clinical study on the addition of preventive EST and pancreatic duct stenting in patients with residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct at completion of ERCP is expected.

In addition, development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP was a strong risk factor of sPEP. In our facility, cannulation is intended to be followed by 25-50 mg dose of rectal indomethacin only when abdominal pain exceeded restraining pain. Elmunzer et al[14] reported that rectal indomethacin significantly reduced the incidence of PEP in patients with a PEP risk factor. On the other hand, Levenick et al[13] reported that the preventive rectal indomethacin does not always inhibit PEP in all ERCP-applied cases. They mentioned that the rectal indomethacin can prevent PEP only in patients with a risk factor of PEP, and its indication should be reconsidered. Moreover, 100 mg of indomethacin is excessive for Japanese with a relatively small physique, and not all ERCP cases are treated with rectal indomethacin at our facility. Furthermore, this treatment inhibited some cases of PEP, but it did not prevent the progression to sPEP in our study. This might have been due to differences in the indication of the rectal indomethacin.

There are several limitations in this study. No diagnosis by exclusion based on the indication and intervention was established. Since it was a retrospective study performed at a single institution, the sample size was small. However, risk factors of sPEP were clarified and these may contribute to demonstrate appropriate conditions and methods to prevent sPEP. As discussed with many PEP-inhibitory methods, the addition of preventive techniques, such as EST and pancreatic duct stenting, and preventive drug administration, such as rectal indomethacin, should be performed after clarifying risk factors of sPEP.

Residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct at completion of ERCP and development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP are risk factors of sPEP. The presence of these findings is an indication of therapeutic intervention for sPEP, and a method to avoid it should be considered.

Cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis (PEP) is an unavoidable endoscopic complication for pancreatobiliary systems. Since PEP is a predictable pathology, and if discovered and appropriately treated early many patients rapidly recover. However, some cases aggravate to a severe state and become fatal. Therefore, it is important to identify factors leading PEP to a severe state.

There are many reports about risk factors of PEP; however, there are few reports to assess the risk factors of severe PEP (sPEP).

Significant differences were noted in residual enhancement of the pancreatic duct and development of abdominal pain showing that these were independent risk factors of sPEP.

The presence of residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct at completion of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP is an indication of therapeutic intervention for sPEP, and a method to avoid it should be considered.

PEP is one of the major adverse events of ERCP. Some PEP aggravate to severe state as sPEP. sPEP sometimes results in the death, so that it has been the most concern still now.

This is a unique single center retrospective study with a significant number of patients investigating an important topic, the risk factors of severe PEP and clarify the indication of prophylactic treatments. The results have a clinical impact on detecting the patients in need for therapeutic intervention for preventing severe PEP; patients with residual contrast medium in the pancreatic duct at completion of ERCP and development of abdominal pain within 3 h after completion of ERCP. This is a well-written article; the manuscript is concise, clear, comprehensive, and convincing.

| 1. | Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, Overby CS, Aas J, Ryan ME, Bochna GS. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 853] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Loperfido S, Angelini G, Benedetti G, Chilovi F, Costan F, De Berardinis F, De Bernardin M, Ederle A, Fina P, Fratton A. Major early complications from diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 801] [Cited by in RCA: 782] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Masci E, Toti G, Mariani A, Curioni S, Lomazzi A, Dinelli M, Minoli G, Crosta C, Comin U, Fertitta A. Complications of diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 617] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Williams EJ, Taylor S, Fairclough P, Hamlyn A, Logan RF, Martin D, Riley SA, Veitch P, Wilkinson ML, Williamson PR. Risk factors for complication following ERCP; results of a large-scale, prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2007;39:793-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Akashi R, Kiyozumi T, Tanaka T, Sakurai K, Oda Y, Sagara K. Mechanism of pancreatitis caused by ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:50-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakahara K, Okuse C, Suetani K, Michikawa Y, Kobayashi S, Otsubo T, Itoh F. Need for pancreatic stenting after sphincterotomy in patients with difficult cannulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8617-8623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ito K, Fujita N, Kanno A, Matsubayashi H, Okaniwa S, Nakahara K, Suzuki K, Enohara R. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis in high risk patients who have undergone prophylactic pancreatic duct stenting: a multicenter retrospective study. Intern Med. 2011;50:2927-2932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sofuni A, Maguchi H, Mukai T, Kawakami H, Irisawa A, Kubota K, Okaniwa S, Kikuyama M, Kutsumi H, Hanada K. Endoscopic pancreatic duct stents reduce the incidence of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis in high-risk patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:851-858; quiz e110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518-1524. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fazel A, Quadri A, Catalano MF, Meyerson SM, Geenen JE. Does a pancreatic duct stent prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis? A prospective randomized study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:291-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harewood GC, Pochron NL, Gostout CJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial of prophylactic pancreatic stent placement for endoscopic snare excision of the duodenal ampulla. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tsuchiya T, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Kawai T, Moriyasu F. Temporary pancreatic stent to prevent post endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis: a preliminary, single-center, randomized controlled trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:302-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Levenick JM, Gordon SR, Fadden LL, Levy LC, Rockacy MJ, Hyder SM, Lacy BE, Bensen SP, Parr DD, Gardner TB. Rectal Indomethacin Does Not Prevent Post-ERCP Pancreatitis in Consecutive Patients. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:911-917; quiz e19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Elmunzer BJ, Scheiman JM, Lehman GA, Chak A, Mosler P, Higgins PD, Hayward RA, Romagnuolo J, Elta GH, Sherman S. A randomized trial of rectal indomethacin to prevent post-ERCP pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-1422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Takenaka M, Fujita T, Sugiyama D, Masuda A, Shiomi H, Sugimoto M, Sanuki T, Hayakumo T, Azuma T, Kutsumi H. What is the most adapted indication of prophylactic pancreatic duct stent within the high-risk group of post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis? Using the propensity score analysis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2088] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, Pilotto A, Forlano R. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dumonceau JM, Andriulli A, Deviere J, Mariani A, Rigaux J, Baron TH, Testoni PA. European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline: prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2010;42:503-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El Nakeeb A, Malak M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL