Published online Apr 16, 2017. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.162

Peer-review started: August 16, 2016

First decision: September 2, 2016

Revised: December 30, 2016

Accepted: January 11, 2017

Article in press: January 14, 2017

Published online: April 16, 2017

Processing time: 244 Days and 9 Hours

To compare the impact of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) on weight loss and obesity related comorbidities over two year follow-up via case control study design.

Forty patients undergoing LRYGB, who completed their two year follow-up were matched with 40 patients undergoing LSG for age, gender, body mass index and presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Data of these patients was retrospectively reviewed to compare the outcome in terms of weight loss and improvement in comorbidities, i.e., T2DM, hypertension (HTN), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), hypothyroidism and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Percentage excess weight loss (EWL%) was similar in LRYGB and LSG groups at one year follow-up (70.5% vs 66.5%, P = 0.36) while it was significantly greater for LRYGB group after two years as compared to LSG group (76.5% vs 67.9%, P = 0.04). The complication rate after LRYGB and LSG was similar (10% vs 7.5%, P = 0.99). The median duration of T2DM and mean number of oral hypoglycemic agents were higher in LRYGB group than LSG group (7 years vs 5 years and 2.2 vs 1.8 respectively, P < 0.05). Both LRYGB and LSG had significant but similar improvement in T2DM, HTN, OSAS and hypothyroidism. However, GERD resolved in all patients undergoing LRYGB while it resolved in only 50% cases with LSG. Eight point three percent patients developed new-onset GERD after LSG.

LRYGB has better outcomes in terms of weight loss two years after surgery as compared to LSG. The impact of LRYGB and LSG on T2DM, HTN, OSAS and hypothyroidism is similar. However, LRYGB has significant resolution of GERD as compared to LSG.

Core tip: Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are the most popular bariatric procedures. Few studies have compared the outcomes of LSG vs LRYGB in terms of weight loss and comorbidity resolution, especially in India. Using case control design in a well-matched population of 40 patients each undergoing LSG and LRYGB, we found similar weight loss one year after surgery in both the groups but the weight loss was significantly higher in LRYGB group two years after surgery. The complication rate was similar in both groups. Regarding comorbidity resolution, both LRYGB and LSG had significant but similar impact on obesity related comorbidities except gastroesophageal reflux disease where LRYGB showed better improvement. This is also among the first few studies to study the impact of bariatric surgery on hypothyroidism.

- Citation: Garg H, Priyadarshini P, Aggarwal S, Agarwal S, Chaudhary R. Comparative study of outcomes following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy in morbidly obese patients: A case control study. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2017; 9(4): 162-170

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v9/i4/162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v9.i4.162

Bariatric surgery is an effective tool in the management of obesity and its associated comorbidities[1]. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y-gastric bypass (LRYGB) is the current gold standard among the various bariatric procedures performed worldwide[2]. Studies have proven its excellent long term outcomes with low rate of morbidity[3]. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) was introduced as a first step procedure to reduce morbidity in high risk patients followed by either LRYGB or bilio-pancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS)[4]. With increasing experience, LSG has proved its efficacy as a stand-alone procedure in the management of morbid obesity. Compared to LRYGB, LSG has several advantages. LSG is relatively easier to perform, preserves pylorus and antrum resulting in less Dumping syndrome, avoids risk of internal hernia and complications due to gastro-jejunostomy or jejuno-jejunostomy, decreases the risk of nutritional deficiencies and provides accessibility of the remnant stomach via endoscopy, which is important especially in Asian population[5]. However, few studies have compared the effect of LRYGB with LSG on weight loss and obesity associated comorbidities, especially in Indian population[5-10].

This study is among the few studies, in the Indian population, to compare the impact of LSG vs LRYGB on weight loss and obesity related comorbidities in a matched cohort of morbid obese patients over a period of two years.

Data of all patients who underwent LSG and LRYGB at our centre, between January 2008 and March 2015 and completed their two year follow up till March 2016, was retrospectively reviewed using a prospectively collected database. All the patients met the National Institute Health criteria for bariatric surgery. These patients include patients with morbid obesity, i.e., body mass index (BMI) > 40 kg/m2 or patients with BMI > 35 kg/m2 with obesity associated comorbidities. The patients are counseled about the types of bariatric procedures - LSG and LRYGB and the benefits and complications associated with each of the procedures. The patients having severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), long-standing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and with BMI > 50 kg/m2 are preferred for LRYGB. The bariatric procedure for a particular patient is decided mutually based on patient’s preference and surgeon’s viewpoint. The patients undergoing revision surgery or two stage procedure were excluded from the study. Patients undergoing LSG and LRYGB were matched by age, gender, BMI and presence or absence of T2DM. All the procedures were performed by the same surgeon (SA) according to standard surgical protocol. The preoperative workup included blood tests, chest radiography, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, electrocardiogram, abdominal ultrasound and hormonal and nutritional evaluation. The patients were kept on Very Low Calorie Diet (approximately 800 kcal, 60-70 g protein) for two weeks before surgery. The follow-up data upto 2 years was recorded in a study proforma.

LSG: The procedure was performed under general anesthesia in Reverse Trendelenburg position. The sleeve was performed in a standard way. Four ports were used: Three 12 mm and one 5 mm. A self-retaining liver retractor was introduced through a 5-mm incision in the epigastrium. The greater omentum was detached from a point 4 cm from the pylorus up to the angle of His using either ultrasonic shears or a bipolar sealing device. The left crus was completely exposed up to the medial border. A sleeve was created over a 36F gastric calibration tube with sequential firings of a three-row stapler. Intraoperative leak test using methylene blue was done to check the staple line integrity. The remnant stomach was retrieved using one of the port site and port closure was done. A suction drain was placed as needed.

LRYGB: An antecolic and antigastric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass was done with an alimentary limb ranging 100-150 cm and bilio-pancreatic limb of 70 cm as measured from duodeno-jejunal flexure. The procedure was performed under general anesthesia in Reverse Trendelenburg position. A 30- to 50-cc vertical gastric pouch was created. End to side gastro-jejunostomy and side-to-side jejuno-jejunostomy was done using three row stapler. Mesentric defect was sutured in all cases. Intraoperative leak test using methylene blue was done to check for the staple line integrity. A suction drain was placed as needed.

The data collected included patient demographics, preoperative BMI, presence of medical comorbidities, intra- and postoperative complications, weight loss and status of comorbidities after surgery.

The weight of the patients in preoperative period and at annual follow up till two years was recorded. The yearly absolute weight loss and percentage excess weight loss (EWL%) was calculated as described by Deitel et al[11]. Failure of surgery was defined as % EWL < 50% as per Reinhold criteria[12].

T2DM, hypertension (HTN), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), hypothyroidism and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) were assessed so as to determine whether it was aggravated, unchanged, improved or resolved compared to preoperative period.

T2DM: Presence of T2DM was defined as glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level ≥ 6.5% or fasting blood glucose (FBG) ≥ 126 mg/dL. Remission was defined as FBG < 100 mg/dL in the absence of anti-diabetic medications, and improvement was defined as decrease in anti-diabetic medications to maintain normal FBG. HbA1c was not available for all the patients in follow up period and hence was not used in the criteria for remission.

HTN: Presence of HTN included both Stage 1 (blood pressure: 120-159/90-99 mmHg) and Stage 2 (> 160/100 mmHg). Remission was defined as normal blood pressure (< 120/80 mmHg) when off antihypertensive medications as reported by the patient. Improvement in HTN was considered if there was decrease in dosage or number of antihypertensive medications to maintain normal blood pressure.

Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) was defined as apnea hypopnea index (AHI) > 15 events/h or > 5 events/h with typical symptoms[13]. Patients with severe OSAS (AHI > 30 events/h) received night time Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) for atleast 2 wk before surgery. Resolution in OSAS was defined as disappearance of symptoms with patient no longer receiving CPAP therapy. Improvement in OSAS was defined as decrease in the symptoms with no longer need of CPAP therapy. Polysomnography could not be done in all patients in post-operative period and hence AHI could not be used as criteria for remission of OSAS.

Hypothyroidism: Presence of hypothyroidism was defined as patients who were on thyroxine therapy for overt hypothyroidism in preoperative period. Remission was considered if patient showed normal thyroid function tests without any thyroxine therapy. Improvement in hypothyroidism was considered if there was decrease in dosage of thyroxine supplement to maintain normal thyroid function tests.

GERD: The presence of GERD symptoms using GERD severity symptom (GERD-SS) questionnaire[14] and proton pump inhibitors (PPI) intake was assessed preoperatively and at follow up visits. A GERD SS Score > 4 or regular intake of PPI was defined as GERD. The resolution of GERD was defined as disappearance of symptoms when patient was no longer taking PPIs, whereas improvement was defined as a decrease in or disappearance of symptoms with a lower PPI dosage. Worsening of GERD was defined as increase in the symptoms or increase in the dosage of PPI after LSG. De novo GERD was defined as the postoperative development of reflux symptoms in patients who had not experienced GERD before LSG.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Normality of the data was checked using Shapiro-Wilk Test. For continuous variables, results were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (Interquartile range) as appropriate. Comparative analysis was performed using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables. Correlation between data was assessed using Pearson or Spearman Rank Correlation Coefficient (SRCC) as appropriate. Statistical significance was identified as P < 0.05.

Four hundreds and seventy-six patients underwent LSG and 61 patients underwent LRYGB between January 2008 and March 2016 at our centre. Forty patients with primary LRYGB completed their two year follow up and were matched to 40 patients undergoing LSG who also completed this follow up period. Table 1 gives the baseline characteristics of both the groups.

| Parameter | LRYGB group (n = 40) | LSG group (n = 40) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 44.6 ± 10.2 | 44.8 ± 10.2 | NS |

| Gender | |||

| Female, n (%) | 29 (72.5%) | 29 (72.5%) | NS |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | NS |

| Weight (kg) | 109.9 ± 13.9 | 113.6 ± 15.2 | NS |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 43.9 ± 5.5 | 45.8 ± 4.8 | NS |

| Excess weight (kg) | 46.9 ± 12.7 | 51.3 ± 12.2 | NS |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 27 (67.5%) | 27 (67.5%) | NS |

| Patients on insulin | 5 (18.5%) | 5 (18.5%) | NS |

| aNumber of OHA | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | |

| abDuration (yr) | 7 (5-7) | 5 (3-7) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 25 (62.5%) | 23 (57.5%) | NS |

| Number of AHA | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | NS |

| OSAS, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 2 (5%) | NS |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 11 (27.5%) | 7 (17.5%) | NS |

| Thyroxine dosage (µg/d) | 90.9 ± 25.7 | 89.9 ± 31.8 | NS |

| GERD, n (%) | 7 (17.5%) | 4 (10%) | NS |

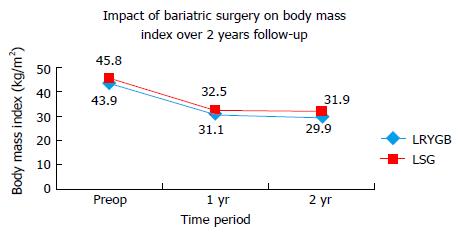

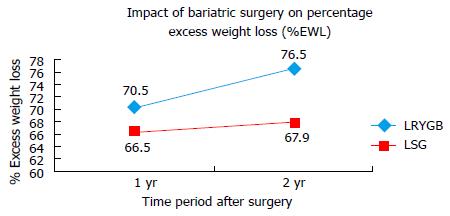

After one year follow-up, the mean BMI (± SD) decreased from 43.9 (± 3.7) kg/m2 to 31.1 (± 4.8) kg/m2 in LRYGB group while 45.8 (± 4.8) kg/m2 to 32.5 (± 4.5) kg/m2 in LSG group (Figure 1). The mean (± SD) %EWL at one year follow-up was 70.5% (± 21.5%) and 66.5% (± 18.6%) in LRYGB and LSG group respectively (Figure 2). Using Student’s t test, there was no significant difference in mean BMI or %EWL one year after either LRYGB or LSG.

At two year follow up, the mean BMI (± SD) BMI declined to 29.9 (± 4.4) kg/m2 and 31.9 (± 4.3) kg/m2 in LRYGB and LSG group respectively (Figure 1). The %EWL at 2-year follow up was 76.7% (± 20.2%) and 67.9% (± 17.9%) in LRYGB and LSG group respectively (Figure 2). This difference was statistically significant with LRYGB having better outcome in terms of weight loss after two years. As per Reinhold’s criteria of failure of surgery, there was 12.5% failure in LRYGB group compared to 20% failure in LSG group two years after the surgery. Figure 1 shows the decline in the weight and associated parameters after LSG and LRYGB.

In our experience of 476 LSG and 61 LRYGB, 6 (1.2%) patients in LSG group and no patient in LRYGB group had post-operative staple line leak. However, among the patients in the study cohort, none of the patient had staple line leak. In the LRYGB group, 2 (5%) patients underwent re-diagnostic laparoscopy and repair for internal hernia, one patient underwent laparoscopy adhesive intestinal obstruction eight months after primary surgery and one patient developed gastro-jejunostomy narrowing with edema which responded to conservative management. In the LSG group, 3 (8.3%) patients developed new-onset GERD in post-operative period managed with medical treatment. Overall, the complication rate in two groups was similar (10% in LRYGB vs 7.5% in LSG group, P = 0.99).

T2DM: Each of the LRYGB and LSG group had 27 patients with 5 patients each on insulin therapy. The median duration of T2DM differed significantly between LRYGB and LSG. The median (IQR) duration of T2DM and mean number of Oral Hypoglycemic Agents (OHA) were significantly higher in LRYGB group as compared to LSG group (Table 1).

On follow up, T2DM resolved in 66.7% (18 out of 27) patients while improved in 33.3% (9 out of 27) patients in LRYGB group. In the LSG group, DM resolved in 77.8% (21 out of 27) while improved in 22.2% (6 out of 27) patients. There was no new-onset T2DM noted in any of the groups. Both the procedures had significant impact on T2DM (P < 0.001). However, the impact of the two procedures on T2DM was comparable (P = 0.544) (Table 2).

| Comorbidity | LRYGB | LSG | P value1 | ||||

| Preoperative | Resolution | Improvement | Preoperative | Resolution | Improvement | ||

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 27 | 18 | 9 | 27 | 21 | 6 | 0.36 |

| Hypertension | 25 | 11 | 12 | 23 | 8 | 14 | 0.64 |

| OSAS | 7 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | - |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 0.58 |

In LRYGB group, all 5 patients, who were on insulin therapy pre-operatively, were off insulin therapy in post-operative period (100%) and the mean number (± SD) of OHA declined significantly from 2.17 (± 0.7) to 0.3 (± 0.5) in post-operative period. In LSG group, 3 out of 5 patients (60%), who were on insulin therapy, continued on insulin therapy with decreased dose in post-operative period and the mean number (± SD) of OHA declined from 1.8 (± 0.7) to 0.3 (± 0.6) in post-operative period. The decrease in number of OHA was similar in two groups (P = 0.736) (Table 3).

| Medications | LRYGB | LSG | P value1 | ||

| Preoperative period | Postoperative period | Preoperative | Postoperative period | ||

| Number of OHA | 2.17 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.73 |

| Number of AHA | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.6 | 0.78 |

| Dosage of thyroxine (μg/d) | 90.9 ± 25.7 | 45.5 ± 40.1 | 89.3 ± 31.8 | 53.6 ± 39.3 | 0.33 |

HTN: Twenty-five patients were hypertensive in LRYGB group and 23 patients were hypertensive in LSG group. After surgery, there was remission in 44% (11 out of 25) patients and improvement in 48% (12 out of 25) patients in LRYGB group. Similarly, there was remission in 34.8% (8 out of 23) patients and improvement in 60.8% (14 out of 23) patients in LSG group (Table 2). The mean number (± SD) of anti-hypertensive agents (AHA) declined from 1.7 (± 0.7) to 0.5 (± 0.5) in LRYGB group and 1.70 (± 0.8) to 0.57 (± 0.59) in LSG group. HTN, thus, improved significantly in both the groups (P < 0.001) but there was no significant difference in the outcome of either of the procedures (Table 3).

OSAS: Seventeen point five percent (7 out of 40) patients in LRYGB group and 5% (2 out of 40) patients in LSG group had severe OSA and were on CPAP therapy preoperatively. All the patients were off CPAP in postoperative period (100%) and showed improvement in symptoms of OSAS, irrespective of the procedure performed (Table 2).

Hypothyroidism: Twenty-seven point five percent (11 out of 40) and 17.5% (7 out of 40) patients were on thyroxine therapy for hypothyroidism in LRYGB and LSG group respectively. Twenty-seven point three percent (3 out of 11) patients in LRYGB group and 14.3% (1 out of 7) patients in LSG group maintained normal thyroid function tests without medications, 54.5% (6 out of 11) patients in LRYGB group and 42.8% (3 out of 7) patients in LSG group showed decrease in the dosage of thyroxine while 18.2% (2 out of 11) patients in LRYGB group and 42.8% (3 out of 7) patients in LSG group had no effect on medication for hypothyroidism (Table 2). The mean dosage of thyroxine decreased from 90.9 (± 25.7) μg to 45.5 (± 40.7) μg in LRYGB group and 89.2 (± 31.8) μg to 53.6 (± 39.3) μg in LSG group (Table 3). Both the procedures had significant impact on hypothyroidism but the impact was comparable (P > 0.05).

GERD: Based on GERD-SS questionnaire, 17.5% (7 out of 40) patients had GERD preoperatively in LRYGB group which resolved completely after surgery. In LSG group, 10% (4 out of 40) patients had GERD preoperatively which resolved in 50% (2 out of 4) patients while remained same in rest of them. There was no new onset GERD in LRYGB group but 8.3% (3 out of 36 patients) developed new-onset GERD in LSG group.

In this study, we compared the outcomes of the two most commonly performed bariatric procedures- LSG and LRYGB in a well-matched morbidly obese population. We found the weight loss was similar at one year follow-up; however, weight loss was significantly higher in LRYGB group at two year follow-up. The complication rate was similar in both the groups. Regarding the impact on comorbidities, there was similar impact on T2DM, HTN, OSA and hypothyroidism. However, LRYGB led to better outcome in long-standing diabetics on insulin therapy.

The impact of LSG and LRYGB on BMI and weight associated parameters was significant over a follow-up of two years. We found %EWL for LRYGB vs LSG at 1-year and 2-year follow-up as 70.5% vs 66.5% (P = 0.36) and 76.7% vs 67.9% (P = 0.044) respectively. As per Reinhold’s criteria[12], there was 20% failure in LSG group compared to 12.5% in LRYGB group. This suggests LRYGB had better outcome on weight loss over two years as compared to LSG. Similar results were reported by other studies. Lakdawala et al[10] reported similar weight loss at one year follow up in 100 patients undergoing LSG and LRYGB. El Chaar et al[9] found %EWL of 75% with LRYGB as compared to 60% with LSG over two year follow up period. Boza et al[6] also reported significantly higher %EWL with LRYGB (94% vs 84%) over two year follow-up in 786 patients undergoing LRYGB and 811 patients undergoing LSG. Such higher %EWL could be explained by lower initial BMI of 38 kg/m2 in their study population. Nonetheless, there was lesser %EWL in LSG group. Li et al[7] in a meta-analysis involving 196 patients undergoing LRYGB and 200 patients undergoing LSG found significantly higher weight loss with LRYGB. The swiss multicentre bypass or sleeve study (SM-BOSS) - a prospective randomised controlled trial published its early results involving 107 patients undergoing LSG and 110 patients undergoing LRYGB[8]. They reported 77% and 73% excess BMI Loss (EBMIL) at one year follow-up and 73% and 63% EBMIL at three year follow-up after LRYGB and LSG respectively (P = 0.02)[8]. On the contrary, few studies have reported better outcome in weight loss with LSG at one year follow-up. Karamanakos et al[15] found %EWL of 69.7% in LSG group compared to 60.5% in LRYGB group, which they explained due to decreased ghrelin levels which suppressed appetite in initial period after surgery. Boza et al[6] also reported 10% and 5.4% failure rate of LSG and LRYGB at follow up of two years. As compared to our study, such lower failure rates could be due to involvement of less obese patients with mean BMI of 38 kg/m2 in their study.

Both LRYGB and LSG had positive impact on T2DM. We found similar rate of improvement in both the groups. Unlike LSG, all patients on insulin therapy in LRYGB group were off insulin therapy in post-operative period. Buchwald et al reported 83% remission rate of T2DM with LRYGB in a meta-analysis involving more than 22000 patients[16]. Boza et al[6] found similar remission rate in LRYGB and LSG group (91% vs 87% respectively). Lakdawala et al[10] showed 100% and 98% remission rate of T2DM with LRYGB and LSG respectively. Inclusion of lower BMI patients with only 7 and 17 diabetics in LSG and LRYGB groups respectively and shorter duration of diabetes could be the possible reasons for such high rate of remission. They also explained the better results in Asian population could be due to decreased insulin resistance with decrease in central obesity which was more prevalent in Asian population. Other studies by Zhang et al[5] and Peterli et al[8] also showed similar remission rate of T2DM with LRYGB and LSG. On the contrary, Li et al[7] in a meta-analysis reported significantly better remission (Odds ratio = 9.08) of T2DM with LRYGB as compared to LSG. Similar results were reported by Lee et al[17].

Multiple mechanisms for remission of T2DM with LRYGB had been proposed. Foregut hypothesis, hindgut hypothesis, decreased ghrelin secretion and starvation followed by weight loss are among the major mechanisms[18]. The mechanism for remission of T2DM post LSG is still not completely understood. The possible mechanism include rise in post-prandial glucagon like peptide-1 due to increase in gastric emptying which lead to increase in insulin secretion. LSG also leads to decrease ghrelin and leptin levels which play role in glucose homeostasis after surgery[19].

The impact of LRYGB and LSG on HTN is variable. Sixty-two point five percent patients and 57.5% patients were hypertensive in LRYGB and LSG group respectively. We found remission rate of 44% and 35% and improvement in 48% and 60.8% in LRYGB and LSG groups respectively. Overall, both the procedures had similar impact on HTN. Similar results were shown by SM-BOSS[8]. Boza et al[6] showed 92% and 80% improvement in HTN with LRYGB and LSG respectively. In a study on Indian population, Lakadawala et al[10] showed 95% and 91% resolution in HTN. The possible mechanism for resolution of HTN would be decrease in the intra-abdominal pressure and Renin-Angiotension Aldosterone System activity after surgery[20].

Seventeen point five percent patients in LRYGB group and 50% patients in LSG group had severe OSA and were on CPAP therapy preoperatively. All the patients were off CPAP therapy with improvement in symptoms in post-operative period. Similar results were shown by other studies. Zhang et al[5] reported 82% and 91% resolution of OSA one year after LRYGB and LSG respectively. They found earlier resolution at 3-6 mo with LRYGB as compared to LSG.

The impact of bariatric surgery on hypothyroidism is less studied. Both LRYGB and LSG had significant impact on need of thyroxine in post-operative period. Eighty-one point eight percent and 57.2% patients showed improvement in hypothyroidism. The improvement was similar in the two groups. Raftopoulos et al[21] reported 48% remission rate with complete resolution in 8% in 23 patients of hypothyroidism undergoing LRYGB. Ruiz-Tovar et al[22] found significant decrease in TSH level after LSG. Another study from our centre showed significant decrease in requirement of thyroxine after LSG[23]. Gkotsina et al[24] reported significant improvement in pharmacokinetic parameters of levo-T4 absorption after LSG while these remained same after LRYGB. Lips et al[25] compared restrictive and malabsorptive procedures and concluded that thyroid hormone regulation is directly proportional to the weight loss irrespective of the bariatric procedure. Hypothyroidism in obese individuals is partially mediated by increased leptin level and peripheral hormonal resistance. Weight loss leads to decrease in the hormone resistance and the need of thyroxine. However, certain subset of patients showed no effect of surgery on hypothyroidism probably because of other factors including autoimmune thyroid disorders[23].

GERD is commonly associated with obesity. While LRYGB led to resolution of GERD in all the patients, LSG led to improvement in GERD in only 50% cases. Importantly, 8.3% developed new onset GERD. Similar results were reported by Lakdawala et al[10]. They found 100% remission in GERD post LRYGB while reported rise in incidence in GERD from 5% to 9% after LSG. SM-BOSS trial also showed significantly higher remission in GERD with LRYGB as compared to LSG and reported 12.5% new onset GERD in LSG group[8]. Frezza et al[26] reported significant decrease in GERD-related symptoms over the 3-year study after LRYGB. Mechanisms of the anti-reflux effect of RYGB include promoting weight loss, lowering acid production in the gastric pouch, diverting bile from the Roux limb, rapid pouch emptying, and decreasing abdominal pressure over the LES[27]. The impact of LSG on GERD is still an unresolved issue. Multiple mechanisms have been proposed for the impact of LSG on GERD. The mechanisms for improvement of GERD after surgery include faster gastric emptying time, decreased gastric reservoir function, decrease intra-abdominal pressure, decreased acid production and alteration in neuro-hormonal mileu of gastrointestinal tract. Factors which may lead to exacerbation or new onset GERD include increased intraluminal pressure, modification in esophago-gastric junction, partial sectioning of sling fibres and presence of hiatus hernia[28].

Overall both LSG and LRYGB has similar effect on obesity related comorbidities over two year follow-up period, although GERD showed significantly better improvement with LRYGB.

The strengths of the study include well matched groups eliminating bias due to confounding factors and the standardized technique performed by same surgeon in all cases. The outcome of LSG in terms of weight loss and comorbidity resolution has been standardized. Our study is among the first few studies to compare the effect of LSG and LRYGB on thyroid disorder.

There are several limitations of this study. Retrospective nature of the study comes with inherent bias. Small sample size with short-term follow up is another limitation. The duration of T2DM and mean number of OHA were higher in LRYGB group than in LSG group, thereby, leading to a potential bias. The definition of comorbidities and its resolution were not optimally standardized. For T2DM, HbA1c was not available for all patients and hence could not be used in criteria for remission. For HTN, self-reporting of normal blood pressure by the patient was taken as remission or improvement. For OSAS, postoperative polysomnography was not available to objectively document the improvement in OSAS. For GERD, no objective measurement including pH-metry, impedance and high resolution manometry was done. Hyperlipidemia and cardiovascular risk factors could not be studied even knowing that myocardial infarction is the most common cause of mortality in this population.

In conclusion, our results indicate LRYGB has better outcomes in terms of weight loss two years after surgery as compared to LSG. The impact of LRYGB and LSG on T2DM, HTN and OSAS was similar. However, LRYGB had significant resolution of GERD as compared to LSG. Further comparative trials with large sample size and long term follow-up are needed to identify the ideal procedure of bariatric surgery.

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are among the most frequently performed bariatric procedures worldwide. Compared to LRYGB, LSG is relatively easier to perform and is associated with less Dumping syndrome, avoids risk of internal hernia and complications due to gastro-jejunostomy or jejuno-jejunostomy, decreases the risk of nutritional deficiencies and provides accessibility of the remnant stomach via endoscopy, which is important especially in Asian population. However, few studies have compared the effects of LRYGB and LSG in well-matched Indian population.

Few studies have compared the outcomes of LRYGB and LSG in a well matched Indian obese population undergoing bariatric surgery.

This study compared 40 patients undergoing LRYGB, who completed their 2-year follow-up with 40 patients undergoing LSG matched for age, gender, body mass index and presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Data of these patients was retrospectively reviewed to compare the outcome in terms of weight loss and improvement in comorbidities, i.e., T2DM, hypertension (HTN), obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS), hypothyroidism and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Using case control design , this study found similar weight loss one year after surgery in both the groups but the weight loss was significantly higher in LRYGB group two years after surgery. The complication rate was similar in both groups. Regarding comorbidity resolution, both LRYGB and LSG had significant but similar impact on obesity related comorbidities except gastroesophageal reflux disease where LRYGB showed better improvement. This is also among the first few studies to study the impact of bariatric surgery on hypothyroidism, which improved significantly in both LSG and LRYGB groups.

This study compares the outcomes of LRYGB with LSG in a well-matched population over a period of two years follow-up. This is important in clinical practice as the impact of LRYGB and LSG on weight loss and obesity associated comorbidities is a casue of concern while selecting a particular bariatric procedure for a patient.

Percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) is defined as [(Preoperative weight-current weight/preoperative weight-ideal weight] × 100%.

This is a retrospective study to compare the impact of LRYGB and LSG on weight loss and obesity related comorbidities. This is an important issue in clinics.

| 1. | Rubino F, Kaplan LM, Schauer PR, Cummings DE. The Diabetes Surgery Summit consensus conference: recommendations for the evaluation and use of gastrointestinal surgery to treat type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 2010;251:399-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Clinical Issues Committee of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. Updated position statement on sleeve gastrectomy as a bariatric procedure. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nguyen NT, Paya M, Stevens CM, Mavandadi S, Zainabadi K, Wilson SE. The relationship between hospital volume and outcome in bariatric surgery at academic medical centers. Ann Surg. 2004;240:586-593; discussion 593-594. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Regan JP, Inabnet WB, Gagner M, Pomp A. Early experience with two-stage laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass as an alternative in the super-super obese patient. Obes Surg. 2003;13:861-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 603] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang N, Maffei A, Cerabona T, Pahuja A, Omana J, Kaul A. Reduction in obesity-related comorbidities: is gastric bypass better than sleeve gastrectomy? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1273-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boza C, Gamboa C, Salinas J, Achurra P, Vega A, Pérez G. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a case-control study and 3 years of follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li JF, Lai DD, Ni B, Sun KX. Comparison of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass with laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Surg. 2013;56:E158-E164. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Peterli R, Borbély Y, Kern B, Gass M, Peters T, Thurnheer M, Schultes B, Laederach K, Bueter M, Schiesser M. Early results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2013;258:690-694; discussion 695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | El Chaar M, Hammoud N, Ezeji G, Claros L, Miletics M, Stoltzfus J. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a single center experience with 2 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 2015;25:254-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lakdawala MA, Bhasker A, Mulchandani D, Goel S, Jain S. Comparison between the results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in the Indian population: a retrospective 1 year study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deitel M, Greenstein RJ. Recommendations for reporting weight loss. Obes Surg. 2003;13:159-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 212] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Reinhold RB. Critical analysis of long term weight loss following gastric bypass. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;155:385-394. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, Ramar K, Rogers R, Schwab RJ, Weaver EM. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263-276. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, Badalamenti S, Pantalena M, Savarino V, Di Mario F, Battaglia G, Mela GS, Pilotto A. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1106-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 397] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Karamanakos SN, Vagenas K, Kalfarentzos F, Alexandrides TK. Weight loss, appetite suppression, and changes in fasting and postprandial ghrelin and peptide-YY levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy: a prospective, double blind study. Ann Surg. 2008;247:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 34.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ, Bantle JP, Sledge I. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122:248-256.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1816] [Cited by in RCA: 1752] [Article Influence: 103.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee SK, Heo Y, Park JM, Kim YJ, Kim SM, Park do J, Han SM, Shim KW, Lee YJ, Lee JY. Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass vs. Sleeve Gastrectomy vs. Gastric Banding: The First Multicenter Retrospective Comparative Cohort Study in Obese Korean Patients. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:956-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thaler JP, Cummings DE. Minireview: Hormonal and metabolic mechanisms of diabetes remission after gastrointestinal surgery. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2518-2525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vigneshwaran B, Wahal A, Aggarwal S, Priyadarshini P, Bhattacharjee H, Khadgawat R, Yadav R. Impact of Sleeve Gastrectomy on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, Gastric Emptying Time, Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 (GLP-1), Ghrelin and Leptin in Non-morbidly Obese Subjects with BMI 30-35.0 kg/m(2): a Prospective Study. Obes Surg. 2016;26:2817-2823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sugerman HJ, Wolfe LG, Sica DA, Clore JN. Diabetes and hypertension in severe obesity and effects of gastric bypass-induced weight loss. Ann Surg. 2003;237:751-756; discussion 757-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Raftopoulos Y, Gagné DJ, Papasavas P, Hayetian F, Maurer J, Bononi P, Caushaj PF. Improvement of hypothyroidism after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2004;14:509-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ruiz-Tovar J, Boix E, Galindo I, Zubiaga L, Diez M, Arroyo A, Calpena R. Evolution of subclinical hypothyroidism and its relation with glucose and triglycerides levels in morbidly obese patients after undergoing sleeve gastrectomy as bariatric procedure. Obes Surg. 2014;24:791-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aggarwal S, Modi S, Jose T. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leads to reduction in thyroxine requirement in morbidly obese patients with hypothyroidism. World J Surg. 2014;38:2628-2631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gkotsina M, Michalaki M, Mamali I, Markantes G, Sakellaropoulos GC, Kalfarentzos F, Vagenakis AG, Markou KB. Improved levothyroxine pharmacokinetics after bariatric surgery. Thyroid. 2013;23:414-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lips MA, Pijl H, van Klinken JB, de Groot GH, Janssen IM, Van Ramshorst B, Van Wagensveld BA, Swank DJ, Van Dielen F, Smit JW. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and calorie restriction induce comparable time-dependent effects on thyroid hormone function tests in obese female subjects. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;169:339-347. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Frezza EE, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Rakitt T, Kingston A, Luketich J, Schauer P. Symptomatic improvement in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1027-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kawahara NT, Alster C, Maluf-Filho F, Polara W, Campos GM, Poli-de-Figueiredo LF. Modified Nissen fundoplication: laparoscopic antireflux surgery after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for obesity. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2012;67:531-533. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Sharma A, Aggarwal S, Ahuja V, Bal C. Evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux before and after sleeve gastrectomy using symptom scoring, scintigraphy, and endoscopy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:600-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aytac E, Chen JQ, Lee CL, Mentes O S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL