Published online Feb 10, 2016. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v8.i3.180

Peer-review started: July 30, 2015

First decision: September 14, 2015

Revised: September 28, 2015

Accepted: October 20, 2015

Article in press: October 27, 2015

Published online: February 10, 2016

Processing time: 190 Days and 17.5 Hours

AIM: To examine the safety of immediate endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) in patients with acute suppurative cholangitis (ASC) caused by choledocholithiasis, as compared with elective EST.

METHODS: Patients with ASC due to choledocholithiasis were allocated to two groups: Those who underwent EST immediately and those who underwent EBD followed by EST 1 wk later because they were under anticoagulant therapy, had a coagulopathy (international normalized ratio > 1.3, partial thromboplastin time greater than twice that of control), or had a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL. One of four trainees [200-400 cases of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)] supervised by a specialist (> 10000 cases of ERCP) performed the procedures. The success and complication rates associated with EST in each group were examined.

RESULTS: Of the 87 patients with ASC, 59 were in the immediate EST group and 28 in the elective EST group. EST was successful in all patients in both groups. There were no complications associated with EST in either group of patients, although white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, total bilirubin, and serum concentrations of liver enzymes just before EST were significantly higher in the immediate EST group than in the elective EST group.

CONCLUSION: Immediate EST can be as safe as elective EST for patients with ASC associated with choledocholithiasis provided they are not under anticoagulant therapy, or do not have a coagulopathy or a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL. Moreover, the procedure was safely performed by a trainee under the supervision of an experienced specialist.

Core tip: Immediate endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) can be as safe as elective EST for patients with acute suppurative cholangitis associated with choledocholithiasis, because there were no complications associated with EST in either group of patients, although white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, total bilirubin, and serum concentrations of liver enzymes just before EST were significantly higher in the immediate EST group (n = 59) than in the elective EST group (n = 28). Moreover, the procedure was safely performed by a trainee under the supervision of an experienced specialist.

- Citation: Ito T, Sai JK, Okubo H, Saito H, Ishii S, Kanazawa R, Tomishima K, Watanabe S, Shiina S. Safety of immediate endoscopic sphincterotomy in acute suppurative cholangitis caused by choledocholithiasis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2016; 8(3): 180-185

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v8/i3/180.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v8.i3.180

Acute suppurative cholangitis (ASC) is a life-threatening condition that requires prompt treatment[1,2]. At present, endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD), including endoscopic nasobiliary drainage (ENBD) and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage (ERBD), followed by elective endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is the established mode of treatment for ASC, with a high success rate and low morbidity and mortality[3-7]. However, the validity of immediate EST with stone extraction is uncertain.

In the present study, we examined the success and complication rates of immediate EST for patients with ASC associated with bile duct stones and compared them with those of elective EST.

Between January 2009 and February 2013, patients with acute cholangitis, suspected of having ASC due to choledocholithiasis were enrolled for the present study. The diagnosis of acute cholangitis was based on clinical evidence of both infection (fever, chills, leukocytosis, or abdominal pain) and biliary obstruction (clinical jaundice or hyperbilirubinemia), and patients with any of the following at admission were suspected of having ASC requiring emergency endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): (1) fever (temperature > 39 °C); (2) septicemic shock (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg); (3) increasing abdominal pain with clinical evidence of peritoneal inflammation (right upper quadrant pain with guarding on palpation); or (4) an impaired level of consciousness on admission. In the present study, ASC was defined based on the evidence of purulent bile. Therefore, patients were included in the current study after bile duct access was gained, the cholangiogram confirmed the presence of bile duct stones, and bile aspiration through the catheter showed the presence of purulent bile on ERCP. Exclusion criteria were prior sphincterotomy, concomitant pancreatic or biliary malignancies, and coexisting intrahepatic stones. Patients who died within 6 h after admission were also excluded.

Patients were allocated to two groups: Immediate EST with stone extraction, and EBD followed by elective EST 1 wk later because they were under anticoagulant therapy, had a coagulopathy (international normalized ratio > 1.3, partial thromboplastin time greater than twice that of control), or had a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL.

Complete blood count, serum electrolytes, clotting profile, and biochemical tests of liver function were monitored daily. Blood pressure, pulse rate, and body temperature were monitored every 4 h. All patients were administered antibiotics intravenously and underwent abdominal CT before ERCP.

Written informed consent for the procedures and treatment was obtained from patients or their next of kin in accordance with normal clinical practice. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Juntendo University.

ERCP was performed using a side-viewing duodenoscope (JF-240, JF-260V, TJF-260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Electrocautery was administered using a 120-watt endocut current (ERBE International, Erlangen, Germany). One of four trainees (200-400 cases of ERCP) supervised by a specialist (>10000 cases of ERCP) performed the procedures. If the trainee could not cannulate the bile duct within 3 min, the specialist did it, and then the trainee was in charge again after deep bile duct cannulation was attained in both groups. All the subjects in the present study started to receive drip infusion of protease inhibitors prior to EST to prevent the occurrence of pancreatitis. Following preparation with pharyngeal anesthesia and intravenous injection of midazolam (0.06 mg/kg), ERCP was performed. After deep cannulation into the bile duct, bile was aspirated to reduce intrabiliary pressure, and low-osmolar nonionic contrast medium was carefully injected to confirm the etiology of cholangitis. After the cholangiogram confirmed the presence of bile duct stones and bile aspiration through the catheter showed the presence of purulent bile, EST or EBD including ENBD and ERBD was performed.

EST was performed with a 30 mm pull-type sphincterotome (Clever Cut 3; KD-V41M, Olympus) under the guidewire. For ENBD, a 6F nasobiliary tube (Gadelius, Tokyo) was inserted in the bile duct. For ERBD, a 7F double pig type plastic endoprosthesis (Wilson-Cook Medical Inc., Winston-Salem, NC) was placed across the papilla. For patients in the immediate EST group, stone removal by retrieval balloon catheter was tried at first ERCP, and EBD (ERBD or ENBD) was performed if the patient had or was suspected of having remnant stones. In the elective EST group, EST was performed 1 wk after EBD for stone removal. After ERCP, all the patients were kept under strict observation.

Procedure-related pancreatitis was defined as abdominal pain, with at least a 3-fold elevation of serum amylase more than 24 h after the procedure. Continuation of preexisting acute pancreatitis was not included as a complication. Hemorrhage was considered clinically significant only if there was clinical evidence of bleeding, such as melena or hematemesis, with an associated decrease of at least 2 g per deciliter of the hemoglobin concentration, or the need for a blood transfusion. Bleeding that was controlled during the procedure without hemodynamic instability or transfusion was not considered a complication[8].

The clinical characteristics of both groups of patients were compared. The primary endpoints of the study were the success and complication rates of immediate EST compared with elective EST. Secondary endpoints were the period for normalization of body temperature, leukocytosis, and C-reactive protein (CRP) leading to discharge from hospital in both groups of patients.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 for Windows. Data are presented as the mean ± SD and were compared using paired t-test. Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparing continuous data with skewed distribution in the two groups. A χ2 test with Yate’s correction was used to analyze gender. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value < 0.05 (two tailed). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Jin Kan Sai from Juntendo University.

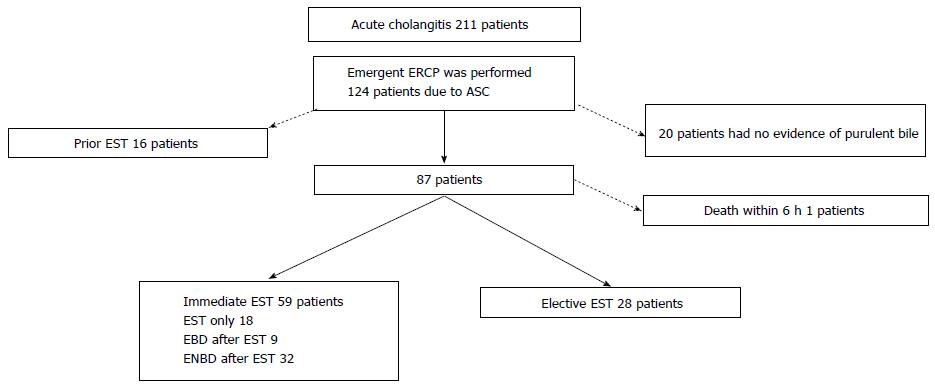

A total of 211 patients were hospitalized for acute cholangitis during the study period, and 124 of them underwent emergency ERCP within 24 h after admission. Sixteen patients were excluded because of prior sphincterotomy.

Thus, 88 had bile duct stones associated with the evidence of purulent bile and were diagnosed as having ASC. Among them, 27 had anticoagulant therapy, and 2 had a coagulopathy with a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL; one of these two patients died within 6 h after successful EBD because of uncontrolled sepsis and multi-organ failure and was excluded from the study. Therefore, there were 59 in the immediate EST group and 28 in the elective EST group (Figure 1). Patient characteristics and demographic data of the patients on admission are shown in Table 1. Patients were significantly older and PT (%) was significantly lower in the elective EST group. Peritonism and pre-existing pancreatitis were more frequent in the immediate EST group. All procedures of EBD were successful, but one patient in the elective EST group had pancreatitis associated with EBD. Demographic data of the two groups just before immediate and elective EST (1 wk after EBD) are shown in Table 2. Compared with the elective EST group, white blood cell count, CRP, total bilirubin, and serum concentrations of liver enzymes before EST were significantly higher in the immediate EST group, while the platelet count was significantly lower.

| Immediate EST group (n = 59) | Elective EST group (n = 28) | P value | |

| Sex (M:F) | 31:28 | 13:15 | 0.59 |

| Age (mean ± SD, range) | 68.76 ± 14.58 | 78.82 ± 9.07 | 0.0001 |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | |||

| Peritonism | 51 (86) | 19 (68) | 0.04 |

| Fever | 28 (47) | 15 (54) | 0.59 |

| Hypotension | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.5) | 0.54 |

| Altered sensorium | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 0.67 |

| Pre-existing pancreatitis (%) | 15 (25) | 1 (3.5) | 0.01 |

| WBC | 10959 ± 5857 | 10025 ± 4110 | 0.39 |

| Plt | 20.4 ± 8.0 | 18.5 ± 6.3 | 0.26 |

| PT (%) | 86.7 ± 15.8 | 72.7 ± 22.2 | 0.009 |

| CRP | 5.32 ± 5.59 | 7.84 ± 6.76 | 0.069 |

| T-Bil | 4.09 ± 2.8 | 3.9 ± 2.5 | 0.76 |

| AST | 253.3 ± 215.2 | 262.3 ± 370.3 | 0.90 |

| ALT | 243.5 ± 182 | 262.3 ± 278.7 | 0.83 |

| γGTP | 458.6 ± 326.7 | 453.4 ± 233.6 | 0.82 |

| ALP | 760.1 ± 404.9 | 826.3 ± 608.4 | 0.60 |

| Immediate EST group | Elective EST group | P value | |

| WBC | 10959 ± 5857 | 6521 ± 2274 | 0.0002 |

| Plt | 20.4 ± 8.0 | 32.6 ± 42.2 | 0.03 |

| PT (%) | 86.7 ± 15.8 | 82.9 ± 14.1 | 0.23 |

| CRP | 5.32 ± 5.59 | 1.82 ± 1.65 | 0.0017 |

| T-Bil | 4.09 ± 2.8 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | < 0.0001 |

| AST | 253.3 ± 215.2 | 50.6 ± 53.5 | < 0.0001 |

| ALT | 243.5 ± 182 | 66.9 ± 55.3 | < 0.0001 |

| γGTP | 458.6 ± 326.7 | 254.3 ± 230.3 | < 0.0001 |

| ALP | 760.1 ± 404.9 | 494.5 ± 241.7 | < 0.0001 |

All EST procedures were successful, and there were no complications such as pancreatitis, bleeding (hemorrhage), or perforation in the two groups, although trainees achieved deep cannulation of the bile duct in 31 (35.6%) of them. Deterioration of pre-existing pancreatitis and cholangitis as a direct result of ERCP is difficult to assess; however, all indicators, including daily serum levels of amylase, liver enzymes, white blood cell count, and CRP, improved after the procedure (data not shown). In the immediate EST group complete stone extraction was achieved at once in 30.5% (18/59) of the patients while 69.5% (41/59) were suspected of having remnant stones and required EBD. Time for normalization of CRP and discharge was significantly shorter in patients who underwent immediate EST and the stones were extracted at once, although the period for normalization of body temperature and leukocytosis was not significantly different between the two groups (Table 3).

| Elective EST group (n = 28) | P value | ||

| Immediate EST group (n = 59) | |||

| Normalization of body temperature | 1.37 ± 1.86 | 1.68 ± 2.83 | 0.6 |

| Normalization of WBC | 2.19 ± 2.87 | 1.39 ± 1.13 | 0.06 |

| Normalization of CRP | 9.12 ± 7.73 | 13.75 ± 9.32 | 0.017 |

| Time to discharge | 16.79 ± 11.89 | 21.75 ± 14.1 | 0.09 |

| Immediate EST with stone extraction group (n = 18) | |||

| Normalization of body temperature | 1.61 ± 0.98 | 1.68 ± 2.83 | 0.92 |

| Normalization of WBC | 1.78 ± 0.9 | 1.39 ± 1.13 | 0.53 |

| Normalization of CRP | 7.0 ± 5.7 | 13.75 ± 9.32 | 0.008 |

| Time to discharge | 13.2 ± 7.5 | 21.75 ± 14.1 | 0.02 |

ASC requires early drainage of the biliary system to reduce the incidence of septic complications[1,2]. The endoscopic techniques used for biliary drainage include EST with stone extraction, and EBD, either ENBD or ERBD. EBD is an established mode of treatment for ASC, with a high success rate and low morbidity and mortality[3-7]. Lin et al[9] reported a 100% success rate and no mortality with ENBD in 40 patients with acute cholangitis. Leung et al[1] treated 105 patients with acute cholangitis by ERBD, with a success rate of 97% and mortality of 4.7%. EBD can be performed easily, quickly, and safely at the endoscopy, avoiding the risk of bleeding in patients with coagulopathy.

On the other hand, EST with stone extraction is another mode of biliary drainage in ASC with an associated mortality rate of 4.7%-7.6%, although EST related complications, such as bleeding, retroduodenal perforation, and acute pancreatitis, may occur in 6%-12% of cases[1,10-12]. The complications associated with EST are most undesirable in acutely ill patients. Moreover, EST cannot be performed in patients with coagulopathy. Therefore, most endoscopists currently prefer EBD to EST as the first treatment for ASC.

In the present study, immediate and elective EST was performed by one of four trainees supervised by one experienced specialist, and there were no complications associated with EST in either group. Therefore we think that EST can be safely performed in patients with ASC by trainees supported by an experienced specialist, although it is undoubtedly that the frequency of post-EST complications is closely related to endoscopic techniques, case volume, skill, and training[13]. Furthermore, despite EBD was conducted as the initial treatment in order to perform EST safely in the elective EST group, in the present study, immediate EST did not increase the risk of post-EST complications provided the patient was not under anticoagulant therapy, or do not have a coagulopathy or a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL, despite patients in the immediate EST group were in worse general conditions than those in the elective EST group at the time of EST. The immediate EST group patients were significantly younger and the occurrence of post-EST complication was not significantly higher than that in older patients of the elective EST group, although Ueki et al[7] reported that younger patients with moderate acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis were likely to experience post-EST pancreatitis and hemorrhage. However, we do not have a clear explanation as to why no complication associated with EST was encountered in these groups of patients, although we suspect that with a larger sample size, complications would occur.

In this study complete stone extraction was achieved in 30.5% (18/59) of patients in the immediate EST group, and 69.5% (41/59) of them suspected of having remnant stones required EBD. Hui et al[4] reported that when endoscopic sphincterotomy is performed with biliary stent insertion in patients with severe acute cholangitis, the procedure is prolonged and the patient is exposed to the risks associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy. However, immediate EST followed by EBD was not associated with an increased frequency of complications in the present study.

Hospitalization of immediate EST patients with stone extraction at once was significantly shorter than that of elective EST patients, and the validity of immediate EST followed by stone extraction was definitive in this aspect for patients with ASC caused by choledocholithiasis. Our results were in line with those of Jang et al[14] who reported that hospitalization of patients with moderate cholangitis subjected to EBD plus EST as the initial treatment (emergency EST) was significantly shorter than that of those who palliatively underwent EST after EBD.

The present study has several limitations. First, patients with anticoagulant therapy, coagulopathy, or platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL were included in the EBD group because they were at high risk for post-EST bleeding. This may have resulted in selection bias. Second, time for the procedure, the volume of contrast, and number of injections made into the bile duct were not monitored. Third, in a review by Freeman et al[15], suspected sphincter Oddi dysfunction (SOD), history of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP), and absence of chronic pancreatitis on the pancreatogram were identified as independent patient-related risk factors for PEP. Moreover, significant procedure-related risk factors were the number of pancreatic duct injections, and difficult or failed cannulation. And we did not examine those factors in the present study, although it is noteworthy that pancreatography was not intended to be performed in the present study. Fourth, this study was done by very experienced endoscopists, limiting to generalize the trial findings. Finally, the present study was not a randomized study, although such trials would be of great interest.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that immediate EST may be equally safe and effective compared with elective EST, and can be definitive for patients with ASC caused by choledocholithiasis provided they are not under anticoagulant therapy, or do not have a coagulopathy or a platelet count < 50000 × 103/μL. Furthermore, EST can be safely performed by a trainee supervised by an experienced specialist even in patients with ASC.

Acute suppurative cholangitis (ASC) is a life-threatening condition that requires prompt treatment. At present, endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD), including endoscopic nasobiliary drainage and endoscopic retrograde biliary drainage, followed by elective endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is the established mode of treatment for ASC, with a high success rate and low morbidity and mortality. However, the validity of immediate EST with stone extraction is uncertain.

To examine the safety of immediate EST in patients with ASC caused by choledocholithiasis, as compared with elective EST.

Patients with ASC due to choledocholithiasis were allocated to two groups: Those who underwent EST immediately and those who underwent EBD electively followed by EST 1 wk later. There were no complications associated with EST in either group of patients, although white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, total bilirubin, and serum concentrations of liver enzymes just before EST were significantly higher in the immediate EST group than in the elective EST group.

The paper may interest readers in particular because immediate EST can be as safe as elective EST for patients with acute suppurative cholangitis associated with choledocholithiasis.

This manuscript “Safety of immediate endoscopic sphincterotomy in acute suppurative cholangitis caused by choledocholithiasis” is very interesting.

| 1. | Leung JW, Chung SC, Sung JJ, Banez VP, Li AK. Urgent endoscopic drainage for acute suppurative cholangitis. Lancet. 1989;1:1307-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, Wong J. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lee DW, Chan AC, Lam YH, Ng EK, Lau JY, Law BK, Lai CW, Sung JJ, Chung SC. Biliary decompression by nasobiliary catheter or biliary stent in acute suppurative cholangitis: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:361-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hui CK, Lai KC, Yuen MF, Ng M, Chan CK, Hu W, Wong WM, Lai CL, Wong BC. Does the addition of endoscopic sphincterotomy to stent insertion improve drainage of the bile duct in acute suppurative cholangitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:500-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Park SY, Park CH, Cho SB, Yoon KW, Lee WS, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS. The safety and effectiveness of endoscopic biliary decompression by plastic stent placement in acute suppurative cholangitis compared with nasobiliary drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:1076-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sharma BC, Kumar R, Agarwal N, Sarin SK. Endoscopic biliary drainage by nasobiliary drain or by stent placement in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy. 2005;37:439-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ueki T, Otani K, Fujimura N, Shimizu A, Otsuka Y, Kawamoto K, Matsui T. Comparison between emergency and elective endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with acute cholangitis due to choledocholithiasis: is emergency endoscopic sphincterotomy safe? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1080-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2086] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Lin XZ, Chang KK, Shin JS, Lin CY, Lin PW, Yu CY, Chou TC. Emergency endoscopic nasobiliary drainage for acute calculous suppurative cholangitis and its potential use in chemical dissolution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1993;8:35-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leese T, Neoptolemos JP, Baker AR, Carr-Locke DL. Management of acute cholangitis and the impact of endoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1986;73:988-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lam SK. A study of endoscopic sphincterotomy in recurrent pyogenic cholangitis. Br J Surg. 1984;71:262-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gogel HK, Runyon BA, Volpicelli NA, Palmer RC. Acute suppurative obstructive cholangitis due to stones: treatment by urgent endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:210-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1703] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Jang SE, Park SW, Lee BS, Shin CM, Lee SH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, Park JK. Management for CBD stone-related mild to moderate acute cholangitis: urgent versus elective ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2082-2087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Freeman ML, Guda NM. Prevention of post-ERCP pancreatitis: a comprehensive review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:845-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Shih SC S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Lu YJ