Published online Jun 25, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i7.747

Peer-review started: August 28, 2014

First decision: September 16, 2014

Revised: April 30, 2015

Accepted: May 8, 2015

Article in press: May 10, 2015

Published online: June 25, 2015

Processing time: 313 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To review results of endoscopic treatment for anastomotic biliary strictures after orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) during an 8-year period.

METHODS: This is a retrospective review of all endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographys (ERCPs) performed between May 2006 and June 2014 in deceased OLT recipients with anastomotic stricture at a tertiary care hospital. Patients were divided into 2 groups, according to the type of stent used (multiple plastic or covered self-expandable metal stents), which was chose on a case-by-case basis and their characteristics. The primary outcome was anastomotic stricture resolution rate determined if there was no more than a minimum waist at cholangiography and a 10 mm balloon could easily pass through the anastomosis with no need for further intervention after final stent removal. Secondary outcomes were technical success rate, number or ERCPs required per patient, number of stents placed, stent indwelling, stricture recurrence rate and therapy for recurrent anastomotic biliary stricture (AS). Stricture recurrence was defined as clinical laboratorial and/or imaging evidence of obstruction at the anastomosis level, after it was considered completely treated, requiring subsequent interventional procedure.

RESULTS: A total of 195 post-OLT patients were assessed for eligibility. One hundred and sixty-four (164) patients were diagnosed with anastomotic biliary stricture. ERCP was successfully performed in 157/164 (95.7%) patients with AS, that were treated with either multiple plastic (n = 109) or metallic billiary stents (n = 48). Mean treatment duration, number of procedures and stents required were lower in the metal stent group. Acute pancreatitis was the most common procedure related complication, occurring in 17.1% in the covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMS) and 4.1% in the multiple plastic stent (MPS) group. Migration was the most frequent stent related complication, observed in 4.3% and 5.5% (cSEMS and MPS respectively). Stricture resolution was achieved in 86.8% in the cSEMS group and in 91% in MPS group. Stricture recurrence after a median follow up of 20 mo was observed in 10 (30.3%) patients in the cSEMS and 7 (7.7%) in the plastic stent group, a statistically significant difference (P = 0.0017). Successful stricture resolution after secondary treatment was achieved in 66.6% and 62.5% of patients respectively in the cSEMS and plastic stents groups.

CONCLUSION: Multiple plastic stents are currently the first treatment option for AS in patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis. cSEMS was associated with increased pancreatitis risk and higher recurrence rate.

Core tip: Endoscopic treatment is effective and safe in the management of post liver transplant biliary complications, mainly for anastomotic strictures. Progressive dilation and multiple plastic stenting have been demonstrated as the best endoscopic therapeutic modality with high success rates and low recurrence. Fully covered stent-expandable metal stents may be an option for endoscopic therapy potentially reducing the number and procedures lowering the costs, however their complication rate needs to be further evaluated.

- Citation: Martins FP, Kahaleh M, Ferrari AP. Management of liver transplantation biliary stricture: Results from a tertiary hospital. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(7): 747-757

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i7/747.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i7.747

Biliary complications have been considered for a long time the “Achilles’ heel” of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), due to its elevated incidence, need for long-term therapy and major impact on graft survival and quality of life. Despite the advances in surgical techniques, organ selection, preservation and immunosuppression, the biliary tract remains the most common site for postoperative complications[1-4].

The incidence of biliary complications varies from 6% up to 40% of patients and includes strictures, leakages, stones, casts, sludge and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction[1-5].

Among the risk factors enrolled in the development of biliary complications the most important are: type of liver transplant procedure, reconstruction technique, organ preservation, technical factors during surgery, reperfusion injury, infection, prolonged cold and warm ischemia, hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis, chronic rejection, ABO incompatibility, underlying disease, donation after cardiac death and older age donor[2-4,6-8].

Diagnosis of biliary complications after liver transplantation is challenging. Patients usually present asymptomatic elevations of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase and/or liver enzymes. Non-specific symptoms such as anorexia, fever, pruritus, jaundice and rarely pain (due to immunosuppression and hepatic denervation) can be observed.

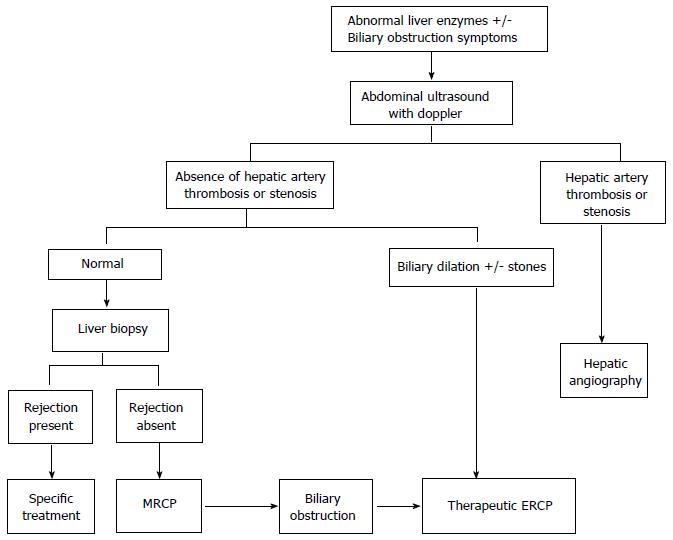

The evaluation should start with an abdominal ultrasound (US) with Doppler of hepatic vessels. If hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis is suspected, angiography should be indicated for specific treatment (Figure 1). If bile duct dilation, stones and/or leakage are identified by US the patient should be referred to therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) or percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography (PTC)[7,9-13]. In case of normal abdominal US, a liver biopsy should be performed to exclude rejection. Finally, in patients with normal US and rejection ruled out by liver histology, a magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) should precede more invasive procedures (Figure 1)[14]. Those patients who have a stricture or leakage confirmed by MRCP will be referred to therapeutic ERCP or PTC according to the type of biliary reconstruction.

Concerning management, although surgical repair used to be the standard treatment in the past, non-operative therapy of biliary complications has become the first line option in the last two decades[3,6]. Endoscopic approach is well established as the preferred therapeutic modality for patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis[15].

This paper will summarize the results of endoscopic treatment for anastomotic biliary strictures after deceased OLT in a tertiary center during an 8-year period and review the literature with future therapy considerations.

Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brazil, is a tertiary care hospital where around 120 liver transplantations are carried out annually. The study was reviewed and approved by the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein Institutional Review Board. We retrospectively evaluated all ERCPs performed between May 2006 and June 2014 in deceased orthotopic liver transplant recipients with duct-to-duct anastomosis and suspected biliary complications. This paper reports our overall experience in such patients. All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment. Procedures were performed under monitored care anesthesia.

Anastomotic biliary stricture (AS) was defined as a dominant short narrowing at the anastomotic site. Patients with AS were individually treated according to standardized protocols either with multiple plastic or single metal stents.

Briefly, plastic stents were initially placed after sphincterotomy and stricture balloon dilation. ERCP was repeated at 3-mo intervals for stent exchange, following a progressive balloon dilation and increasing number of stents protocol at each session, until 12 mo of therapy.

Covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMS) were deployed with or without sphincterotomy and removed after a 3-mo period if a partially covered metal stent-expandable metal stents (PCSEMS) was used or after 6 mo in case of a fully covered stent-expandable metal stents (FCSEMS). In our early experience, biliary SEMS were placed without sphincterotomy, which we started to perform after recognizing a high rate of pancreatitis in these patients. PCSEMS were also used in our early experience, when fully covered SEMS were not available in Brazil.

Complications after ERCP (pancreatitis, cholangitis, hemorrhage, perforation) were defined by established criteria[16].

Initial technical success was the ability to obtain a cholangiogram and accomplish stent placement at ERCP alone or with a trans-hepatic rendezvous procedure. The investigators determined successful stricture resolution if there was no more than a minimum waist at cholangiography and a 10 mm balloon could easily pass through the anastomosis with no need for further intervention after final stent removal. All patients were followed at the institution transplant clinic through a combination of routine laboratory testing and clinical examination protocol. Stricture recurrence was defined as the return of clinical symptoms and/or elevated liver function tests with imaging evidence of obstruction at the anastomosis level causing biliary flow impairment requiring a subsequent interventional procedure in a patient previously considered successfully treated.

The primary outcome was anastomotic stricture resolution rate. Secondary outcomes were technical success rate, number or ERCPs required per patient, number of stents placed, stent indwelling, follow-up duration, stricture recurrence rate and therapy for recurrent AS.

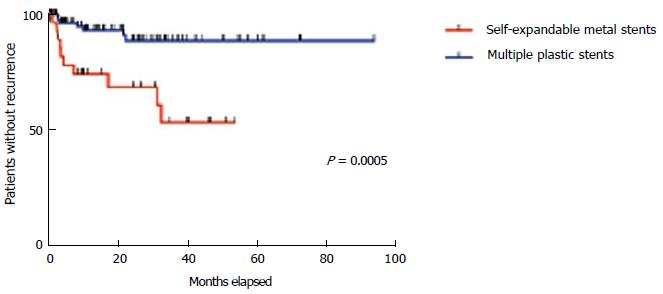

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data. Data was reported as the mean, standard deviation and range. Recurrence data was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical data analysis was performed by the author (Martins FP) and reviewed by Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein Statistics Department.

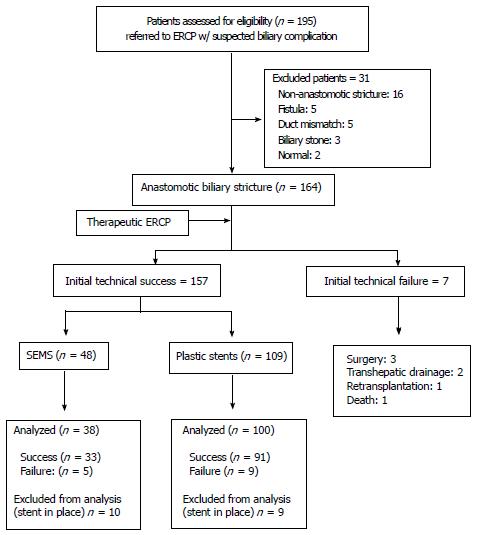

A total of 195 post-OLT patients were referred to our Endoscopy Unit with a suspected biliary complication between May 2006 and June 2014. One hundred and sixty-four (164) patients were diagnosed with anastomotic biliary stricture (Figure 2).

Patients were divided into 2 groups, according to the type of stent used (multiple plastic or covered self-expandable metal stents), which was chosen on a case-by-case basis (Table 1). Both groups were similar concerning gender, age, time from OLT to anastomotic stricture and associated biliary or hepatic artery lesions.

| Multiple plastic stents | cSEMS | |

| n | 109 | 48 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 76 (69.7%) | 36 (75.0%) |

| Female | 33 (30.3%) | 12 (25.0%) |

| Age (yr) | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 48.8 (± 14.5) | 54.5 (± 12.9) |

| Median | 50 | 56.8 |

| Range | 10-75 | 17-73 |

| Time of anastomotic stricture after orthotopic liver transplantation (d) | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 214.2 (± 411.4) | 221.6 (± 263.3) |

| Median | 72 | 115.5 |

| Range | 6-2663 | 8-1339 |

| Hepatic artery associated lesions | ||

| Stenosis | 3 (2.8%) | 3 (6.3%) |

| Thrombosis | 8 (7.3%) | 1 (2.1%) |

| Associated biliary lesions | ||

| Anastomotic fistula | 5 (4.6%) | 2 (4.2%) |

| Non-anastomotic fistula | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Non-anastomotic stricture | 1 (0.9%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cholangitis | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Stones | 2 (1.8%) | 0 (0.0%) |

Among the 164 patients with confirmed post-OLT anastomotic biliary stricture, initial technical success was obtained in 157 (95.7%); 109 individuals being treated with plastic stents and 48 with cSEMS (16 PCSEMS and 32 FCSEMS). Percutaneous trans-hepatic cholangiography was required in 11 (7.0%) patients to achieve access due to high-grade stricture or sharp angulation at the anastomosis. After percutaneous approach cSEMS were used in 7 and plastic stents in 4 cases.

Seven patients failed initial ERCP: 3 were referred to surgery (hepatic-jejunal anastomosis), 2 received external trans-hepatic biliary drainage, one was referred to re-transplantation and one died due to multiple organ failure after an episode of severe acute pancreatitis.

A total of 341 ERCPs were performed. Ten patients in the cSEMS group and 9 in the plastic stent group still have the stents in place and were excluded from analysis. Mean treatment duration, number of procedures and stents required were lower in the metal stent group (Table 2).

| Multipleplastic stents | cSEMS | |

| Total number of ERCP | 271 | 70 |

| Stent treatment duration (d) | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 282.7 (± 135.4) | 124.2 (± 67.9) |

| Median | 322 | 107.5 |

| Range | 3-767 | 9-269 |

| Number of ERCP per patient | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 3.9 (± 1.5) | 2.0 |

| Median | 4 | 2.0 |

| Range | 1-7 | - |

| Number of stents per ERCP session | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 2.9 (± 1.5) | 1 |

| Median | 3.0 | 1 |

| Range | 1-10 | - |

| Total number of stents per patient | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 10.0 (± 7.2) | 1 |

| Median | 10 | 1 |

| Range | 1-30 | - |

| Complications | 26 (9.6) | 17 (24.3) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 11 (4.1) | 12 (17.1) |

| Bleeding | 7 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Perforation | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cardiorespiratory | 2 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| Bacteremia | 4 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) |

| Pain | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.7) |

| Stent related complications | ||

| Migration | 15 (5.5) | 3 (4.3) |

| Occlusion | 5 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) |

Acute pancreatitis was the most common procedure related complication, occurring in 17.1% in the cSEMS and 4.1% in the plastic stent group (Table 2). Other 4 patients (5.7%) presented abdominal pain without pancreatitis, requiring hospital admission to receive intravenous analgesics. Among stent related complications, migration was the most frequent, observed in 4.3% and 5.5% of patients with metal and plastic stents respectively.

There was one death (0.3%) related to severe acute pancreatitis in one patient who was also a technical failure.

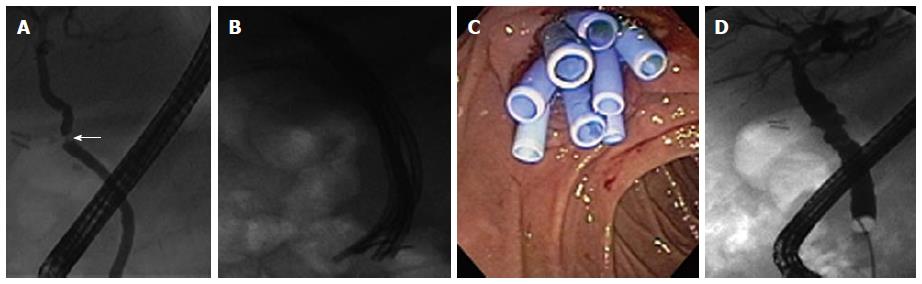

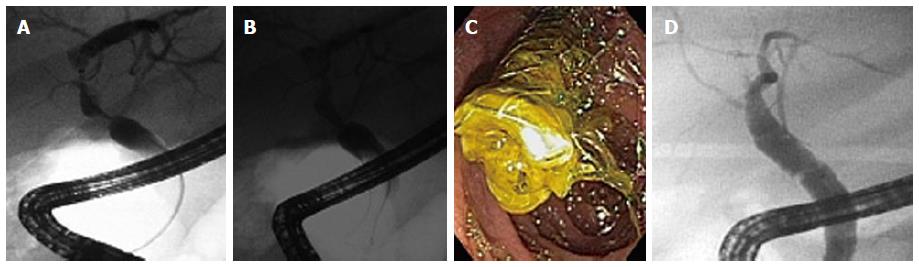

There was no lost of follow-up until the primary outcome. Stricture resolution was achieved in 86.8% in the cSEMS group (Figure 3) and in 91% in the multiple plastic stents group (Figure 4). There were 5 failures in the cSEMS group, two of them presented spontaneous distal stent migration (Figure 5).

Late stricture recurrence was observed in 10 (30.3%) patients in the cSEMS and 7 (7.7%) in the plastic stent group (Table 3). A Kaplan-Meier analysis (Figure 6) disclosed a statistically significant difference in the recurrence rate between both groups (P = 0.0017).

| Multiple plastic stents | cSEMS | |

| n | 100 | 38 |

| Stricture resolution rate | ||

| Success | 91 (91.0) | 33 (86.8) |

| Failure | 9 (9.0) | 5 (13.2) |

| Follow-up (d) | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 690.8 (± 632.6) | 620.3 (± 540.7) |

| Median | 538 | 479 |

| Range | 0-2823 | 0-1615 |

| Recurrence rate | 7 (7.7) | 10 (30.3) |

| Time to recurrent anastomotic stricture (d) | ||

| Mean (± SD) | 296.9 (± 259.5) | 310.0 (± 348.4) |

| Median | 240 | 124 |

| Range | 73-667 | 27-975 |

| Re-treatment after failure or recurrent anastomotic stricture | ||

| Success | 10 (62.5) | 10 (66.6) |

| Failure | 6 (37.5) | 1 (6.7) |

| In treatment | 0 (0.0) | 3 (20.0) |

| Lost of follow-up | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) |

In the cSEMS group, 8 patients received re-treatment with multiple plastic stents, 2 received another cSEMS, 4 were referred to surgery and 1 lost of follow-up. In the multiple plastic stents group, secondary treatment consisted of cSEMS in 9 patients, multiple plastic stents in 4, surgery in 2 and PTC in 1 (choice of treatment in patients who failed initial treatment was decided by the referring physician). The results are summarized in Table 3.

Bile duct strictures after OLT are the most common biliary complication and have been classified according to their location into anastomotic strictures and non-anastomotic. They will be discussed separately in this paper as they differ in pathogenesis, presentation, natural history and response to treatment.

Anastomotic strictures present as a thin, short, localized and isolated narrowing in the area of biliary anastomosis as a result of fibrotic healing arising from ischemia at the end of both the donor and recipient bile duct[4,6,17]. They occur in 5% to 15% of patients after deceased OLT and 19% to 32% after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT)[3,4,6,18,19]. Early presentation (within 12 wk) of anastomotic strictures have been related to technical issues, such as, small caliber of bile ducts, mismatch in size between donor and recipient ducts, inappropriate surgical techniques including suture material, tension at the anastomosis and excessive use of electrocautery[20]. The presence of bile leak has been reported as an independent risk factor for the development of AS; the underlying process may be related to the inflammation and subsequent fibrosis as a local effect caused by the bile itself or it may be a marker of poor vascularity in those patients in whom the leak is not originated from the cystic stump[8,21]. Late strictures are mainly due to vascular insufficiency, ischemia and problems with healing and fibrosis[12,22].

The majority of anastomotic stricture develops within the first year after OLT. In our series, the mean time between OLT and biliary stricture presentation was about 7 mo. Patients usually present asymptomatic or may have non-specific symptoms with abnormalities in liver function chemistries. Clinical suspicious must be confirmed by imaging diagnostic tools and patients are then referred to treatment, accordingly to the algorithm presented above.

There has been a transition over the past two decades in the primary management of benign biliary strictures from surgery to minimally invasive via ERCP. Endoscopic therapy presents a lower complication rate and shorter hospital stay when compared to surgery, not compromising the option of operation in case of failure[23,24]. Percutaneous therapy is still considered a second line option for patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis, though reserved to failed endoscopic access to the anastomotic stricture, and patients with hepaticojejunostomy or choledochojejunostomy reconstruction. Currently surgical revision is confined for patients who have failed endoscopic and percutaneous therapy with re-transplantation being the final option.

Most patients with anastomotic stricture require multiple endoscopic interventions at 3-mo intervals for 12 to 24 mo with balloon dilation and long-term stenting[4,6,7,19,25-29]. The rational for multiple biliary stents placement through the stricture is to maintain the maximal expansion in luminal diameter achieved during balloon dilation, possibly promoting the re-modelation of bile ducts over the stents and preventing duct narrowing when stents are still in place[27,30]. In addition, the use of multiple stents may reduce complications related to stent occlusion, such as obstructive jaundice and cholangitis by adding biliary drainage through interstent channels[27,30,31].

A recent systematic review showed that stricture resolution rates were 78.3% for stent indwelling of less than 12 mo, compared with 97% for those longer than 1 year. The corresponding recurrence rates were 14.2% and 1.5% respectively[32].

In our center, we adopted an aggressive multiple plastic prophylactic stent exchange protocol over 1 year period, achieving a stricture resolution rate of 91%, which compares favorably with literature results. Recurrence rate after a mean follow-up of approximately 2 years is as low as 7.7%, reinforcing the benefits of extending the treatment up to 1 year.

A recent multivariate regression analysis was published assessing the outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after OLT[5]. Patients who received a graft from living donor or from a donor after cardiac death and those who had a reoperation for a non-biliary indication within the first month after liver transplantation were less likely to respond to endoscopic therapy[5]. Another factor apparently associated to stricture recurrence is the presence of a biliary leakage at initial ERCP[33]. On the other hand, early onset strictures seem to respond better and this finding may be related to the fact that those with late-onset are likely to be more fibrotic and therefore tighter and more resistant to therapy[8,27,33,34]. However, in case of recurrence, patients appear to respond well to repeated endoscopic treatment[8,27,30,35].

The major drawbacks of endoscopic treatment with balloon dilation and multiple plastic stents placement are the need of multiple procedures. Partially or fully covered SEMS were introduced on the market and became a very appealing option for benign biliary strictures due to their removability[36-49].

Post OLT biliary strictures offer an anatomical advantage for the placement of SEMS, which is the presence of the graft duct, permitting enough space above the stenosis to accommodate the metal stent distant from the hepatic confluence. Kahaleh et al[44] have been pioneer in the use of SEMS for benign biliary strictures of different etiology. Firstly, by describing metallic stent removability[44] and afterwards testing partially and fully covered SEMS in different clinical and technical settings[42,43,50-52].

Temporary placement of FCSEMS in patients with post-OLT anastomotic strictures refractory to conventional endoscopic therapy reached 87.5% to 100% initial success rate with a 4.5% to 7.4% recurrence. The major drawback of FCSEMS use was migration; occurring in 27.2% to 37.5%, even though with no clinical consequences[36,40,46].

In a systematic review that included 21 studies, multiple plastic stents were compared with metal stents in post liver transplant anastomotic stricture. There was significant heterogeneity in stent protocols, types of SEMS used, the use of balloon dilation or plastic stents before SEMS placement, primary outcome and stent free follow-up. There were no randomized controlled trials or non-randomized studies comparing these two modalities. Two hundred patients treated with SEMS were analyzed and stricture resolution rate was 80% to 94% when stent indwelling was longer than 3 mo, very similar to a 94% to 100% rate seen with multiple plastic stent for at least 12 mo. Moreover SEMS were used as a second line therapy for refractory strictures in 125 of these patients, what can be considered a selection bias for more difficult strictures. The main problem with SEMS was stent migration, occurring in 16% of cases[32]. The rate of stricture resolution is lower in patients with FCSEMS migration[32,46,48].

In our study, we analyzed 38 post OLT patients with anastomotic stricture treated with cSEMS as a first line approach, reaching a stricture resolution of 86.8% after a mean stent indwelling of 124.2 d. Although the initial success was comparable with the currently standard multiple plastic stent treatment, there was a 30.3% recurrence rate after a mean of 310 d. We wonder if this higher recurrence rate was due to the shorter stent indwelling or the smaller final diameter of a 10 mm (30 French) cSEMS compared with the maximum number of plastic stents (up to 90 French per ERCP session) achieved in the other group.

We presented a mid-term evaluation of our randomized controlled trial comparing cSEMS with multiple plastic stents at DDW 2013. Although success rate was similar between groups, mean treatment duration and number of procedures required were statistically lower in cSEMS group (P < 0.001 for both comparisons). Moreover in our prospective trial, the mean total diameter for plastic stent group was 59 French (range 20 to 104.5 French)[47].

In summary, temporary placement of FCSEMS has been demonstrated effective and safe in the treatment of post OLT anastomotic strictures and should be considered for patients with refractory strictures[36,40,42,43,49]. On the basis of the current data, FCSEMS may allow anastomotic biliary stricture resolution with fewer procedure sessions possibly reducing treatment global cost, with the initial high price of a SEMS being compensated by the reduction in the number of ERCPs and the total number of plastic stents used during the 12-mo treatment period[53].

Questions remain about the optimal stenting interval and ideal metal stent. Concerning the first question, FCSEMS may be left in place for longer periods than partially covered ones, but prospective randomized studies with long-term follow-up are necessary to confirm this concept. The pursue for the ideal SEMS is still ongoing, it should be fully covered with an inert and resistant coating and have no fins, which seem to be associated to significant tissue reaction.

Concerning complications rate, in our study, the rate of post procedure acute pancreatitis in the plastic stent group was 4.1%, which compares favorably with the literature reports[54,55]. However, the rate of pancreatitis in the cSEMS group was 17.1%, which is exceedingly high even for a high-risk population.

Biliary sphincterotomy is usually not performed before SEMS placement in malignant biliary obstructions and therefore in the first 16 cases in our study cSEMS were deployed without one. The high incidence of acute pancreatitis (50% in the first 16 cases) came to our attention raising a debate over the impact of the sphincterotomy preceding metal stent deployment in a benign biliary stricture. Moreover, the severity of the event after cSEMS placement without sphincterotomy was also alarming, since 1 case was severe, 5 moderate and 2 mild.

The main hypothesis was that placing a trans-papillary metal stent in a native papilla without prior sphincterotomy was the main reason for the high rate of post procedure pancreatitis. Differently from patients with malignant obstruction that probably have already pancreatic parenchymal atrophy secondary to insidious pancreatic distal obstruction and therefore do not present acute pancreatitis after trans-papillary SEMS[56] Currently in our practice, all cSMES are placed after a biliary sphincterotomy in the post-OLT anastomotic stricture what drastically decreased acute pancreatitis rate to 12.5% (4/32) and all events were mild.

Although advances in surgical technique, organ preservation and selection have been made, biliary complications remain a significant source of morbidity in post liver transplant patients. Endoscopic treatment is already established as standard first line therapy. Progressive balloon dilation and multiple plastic stenting have been considered the first treatment option for biliary stricture in patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis. Our study shows encouraging results regarding placement of biliary cSEMS as the therapeutic endoscopic choice aiming to reduce the number of procedures and thus have a positive impact in cost, morbidity and quality of life of these patients, however their complication rate needs to be further evaluated.

Biliary complications have been considered for a long time the technical “Achiles heel” of orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT), with biliary strictures incidence up to 40% of patients. The standard strategy for post OLT biliary strictures in patients with duct-to-duct anastomosis has been balloon dilation followed by insertion of multiple plastic stents. Recently, covered self-expandable metal stents (cSEMS) has been increasingly used in the management of benign biliary strictures.

The major drawback of conventional endoscopic treatment with multiple plastic stents placement is the need of multiple procedures. cSEMS have removability previously demonstrated in published studies and longer patency. In the area of benign biliary lesions, the current research hotspot is to evaluate the effectiveness and adverse events related to cSEMS.

Current evidence does not suggest a clear advantage of SEMS use over multiple plastic sten. In the study although success rates were similar, mean treatment duration and number of procedures required were statistically lower in cSEMS group. On the basis of the current data, fully covered stent- EMS may allow anastomotic biliary stricture resolution with fewer procedure sessions possibly reducing treatment global cost, with the initial high price of a SEMS being compensated by the reduction in the number of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographys and the total number of plastic stents used during the 12-mo treatment period.

Conventional endoscopic treatment with progressive balloon dilation and multiple plastic stenting has been considered the first option for post-OLT biliary stricture for decades. The study shows encouraging results regarding placement of biliary cSEMS as the therapeutic endoscopic choice aiming to reduce the number of procedures and thus have a positive impact in cost, morbidity and quality of life of these patients, however the complication rate needs to be further evaluated.

Anastomotic biliary strictures in the post-OLT scenario present as a short narrowing at the area of choledochal anastomosis. Endoscopic therapy can be performed by standardized protocols either with multiple plastic or single metal stents. Multiple plastic stents are placed after sphincterotomy and stricture balloon dilation, exchanged at 3-mo interval, until 12 mo of therapy. cSEMS are deployed at the index procedure and removed after approximately 6 mo.

This is a good descriptive study in which the authors analyzed the effectiveness and safety of endoscopic therapy in the management of post-OLT anastomotic biliary stricture. The results are interesting and suggest that cSEMS is a potential therapeutic option to multiple plastic stents that could be used for reducing the number of procedures and overall costs.

| 1. | Fogel EL, McHenry L, Sherman S, Watkins JL, Lehman GA. Therapeutic biliary endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang JM, Lee JM, Suh KS, Yi NJ, Kim YT, Kim SH, Han JK, Choi BI. Biliary complications in living donor liver transplantation: imaging findings and the roles of interventional procedures. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:756-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Akamatsu N, Sugawara Y, Hashimoto D. Biliary reconstruction, its complications and management of biliary complications after adult liver transplantation: a systematic review of the incidence, risk factors and outcome. Transpl Int. 2011;24:379-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 5. | Buxbaum JL, Biggins SW, Bagatelos KC, Ostroff JW. Predictors of endoscopic treatment outcomes in the management of biliary problems after liver transplantation at a high-volume academic center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:37-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Williams ED, Draganov PV. Endoscopic management of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3725-3733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rerknimitr R, Sherman S, Fogel EL, Kalayci C, Lumeng L, Chalasani N, Kwo P, Lehman GA. Biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation with choledochocholedochostomy anastomosis: endoscopic findings and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:224-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, van der Jagt EJ, Limburg AJ, van den Berg AP, Slooff MJ, Peeters PM, de Jong KP, Kleibeuker JH. Anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: causes and consequences. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:726-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Verdonk RC, Buis CI, Porte RJ, Haagsma EB. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: a review. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2006;89-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pfau PR, Kochman ML, Lewis JD, Long WB, Lucey MR, Olthoff K, Shaked A, Ginsberg GG. Endoscopic management of postoperative biliary complications in orthotopic liver transplantation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:55-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thuluvath PJ, Pfau PR, Kimmey MB, Ginsberg GG. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: the role of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pascher A, Neuhaus P. Biliary complications after deceased-donor orthotopic liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:487-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thethy S, Thomson BNj, Pleass H, Wigmore SJ, Madhavan K, Akyol M, Forsythe JL, James Garden O. Management of biliary tract complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:647-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jorgensen JE, Waljee AK, Volk ML, Sonnenday CJ, Elta GH, Al-Hawary MM, Singal AG, Taylor JR, Elmunzer BJ. Is MRCP equivalent to ERCP for diagnosing biliary obstruction in orthotopic liver transplant recipients? A meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:955-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Balderramo D, Bordas JM, Sendino O, Abraldes JG, Navasa M, Llach J, Cardenas A. Complications after ERCP in liver transplant recipients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2086] [Article Influence: 59.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Ostroff JW. Post-transplant biliary problems. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:163-183. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Schlaak J, Malago M, Broelsch CE, Treichel U, Gerken G. Endoscopic therapy of posttransplant biliary stenoses after right-sided adult living donor liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1144-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Graziadei IW, Schwaighofer H, Koch R, Nachbaur K, Koenigsrainer A, Margreiter R, Vogel W. Long-term outcome of endoscopic treatment of biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Koneru B, Sterling MJ, Bahramipour PF. Bile duct strictures after liver transplantation: a changing landscape of the Achilles’ heel. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:702-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Welling TH, Heidt DG, Englesbe MJ, Magee JC, Sung RS, Campbell DA, Punch JD, Pelletier SJ. Biliary complications following liver transplantation in the model for end-stage liver disease era: effect of donor, recipient, and technical factors. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:73-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Testa G, Malagó M, Valentín-Gamazo C, Lindell G, Broelsch CE. Biliary anastomosis in living related liver transplantation using the right liver lobe: techniques and complications. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:710-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dumonceau JM, Devière J, Delhaye M, Baize M, Cremer M. Plastic and metal stents for postoperative benign bile duct strictures: the best and the worst. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:8-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Liotta G, Costa G, Lepre L, Miccini M, De Masi E, Lamazza MA, Fiori E. Management of benign biliary strictures: biliary enteric anastomosis vs endoscopic stenting. Arch Surg. 2000;135:153-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Costamagna G, Tringali A, Mutignani M, Perri V, Spada C, Pandolfi M, Galasso D. Endotherapy of postoperative biliary strictures with multiple stents: results after more than 10 years of follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:551-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Krok KL, Cárdenas A, Thuluvath PJ. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2010;14:359-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pasha SF, Harrison ME, Das A, Nguyen CC, Vargas HE, Balan V, Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Mulligan DC. Endoscopic treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after deceased donor liver transplantation: outcomes after maximal stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:44-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zoepf T, Maldonado-Lopez EJ, Hilgard P, Malago M, Broelsch CE, Treichel U, Gerken G. Balloon dilatation vs. balloon dilatation plus bile duct endoprostheses for treatment of anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Holt AP, Thorburn D, Mirza D, Gunson B, Wong T, Haydon G. A prospective study of standardized nonsurgical therapy in the management of biliary anastomotic strictures complicating liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2007;84:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Tabibian JH, Asham EH, Han S, Saab S, Tong MJ, Goldstein L, Busuttil RW, Durazo FA. Endoscopic treatment of postorthotopic liver transplantation anastomotic biliary strictures with maximal stent therapy (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Morelli J, Mulcahy HE, Willner IR, Cunningham JT, Draganov P. Long-term outcomes for patients with post-liver transplant anastomotic biliary strictures treated by endoscopic stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:374-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kao D, Zepeda-Gomez S, Tandon P, Bain VG. Managing the post-liver transplantation anastomotic biliary stricture: multiple plastic versus metal stents: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:679-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Alazmi WM, Fogel EL, Watkins JL, McHenry L, Tector JA, Fridell J, Mosler P, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Recurrence rate of anastomotic biliary strictures in patients who have had previous successful endoscopic therapy for anastomotic narrowing after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2006;38:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Thuluvath PJ, Atassi T, Lee J. An endoscopic approach to biliary complications following orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2003;23:156-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Morelli G, Fazel A, Judah J, Pan JJ, Forsmark C, Draganov P. Rapid-sequence endoscopic management of posttransplant anastomotic biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | García-Pajares F, Sánchez-Antolín G, Pelayo SL, Gómez de la Cuesta S, Herranz Bachiller MT, Pérez-Miranda M, de La Serna C, Vallecillo Sande MA, Alcaide N, Llames RV. Covered metal stents for the treatment of biliary complications after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2966-2969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chaput U, Scatton O, Bichard P, Ponchon T, Chryssostalis A, Gaudric M, Mangialavori L, Duchmann JC, Massault PP, Conti F. Temporary placement of partially covered self-expandable metal stents for anastomotic biliary strictures after liver transplantation: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1167-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Tee HP, James MW, Kaffes AJ. Placement of removable metal biliary stent in post-orthotopic liver transplantation anastomotic stricture. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:3597-3600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Marín-Gómez LM, Sobrino-Rodríguez S, Alamo-Martínez JM, Suárez-Artacho G, Bernal-Bellido C, Serrano-Díaz-Canedo J, Padillo-Ruiz J, Gómez-Bravo MA. Use of fully covered self-expandable stent in biliary complications after liver transplantation: a case series. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2975-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Traina M, Tarantino I, Barresi L, Volpes R, Gruttadauria S, Petridis I, Gridelli B. Efficacy and safety of fully covered self-expandable metallic stents in biliary complications after liver transplantation: a preliminary study. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1493-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vandenbroucke F, Plasse M, Dagenais M, Lapointe R, Lêtourneau R, Roy A. Treatment of post liver transplantation bile duct stricture with self-expandable metallic stent. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:202-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mahajan A, Ho H, Sauer B, Phillips MS, Shami VM, Ellen K, Rehan M, Schmitt TM, Kahaleh M. Temporary placement of fully covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: midterm evaluation (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:303-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kahaleh M, Behm B, Clarke BW, Brock A, Shami VM, De La Rue SA, Sundaram V, Tokar J, Adams RB, Yeaton P. Temporary placement of covered self-expandable metal stents in benign biliary strictures: a new paradigm? (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:446-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kahaleh M, Tokar J, Le T, Yeaton P. Removal of self-expandable metallic Wallstents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:640-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Trentino P, Falasco G, d’orta C, Coda S. Endoscopic removal of a metallic biliary stent: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:321-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Devière J, Nageshwar Reddy D, Püspök A, Ponchon T, Bruno MJ, Bourke MJ, Neuhaus H, Roy A, González-Huix Lladó F, Barkun AN. Successful management of benign biliary strictures with fully covered self-expanding metal stents. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:385-395; quiz e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Martins FP, Di Sena V, de Paulo GA, Contini ML, Ferrari Junior AP. Phase III randomized controlled trial of fully covered metal stent versus multiple plastic stents in anastomotic biliary strictures following orthotopic liver transplantation: midterm Evaluation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:AB318. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 48. | Kahaleh M, Brijbassie A, Sethi A, Degaetani M, Poneros JM, Loren DE, Kowalski TE, Sejpal DV, Patel S, Rosenkranz L. Multicenter trial evaluating the use of covered self-expanding metal stents in benign biliary strictures: time to revisit our therapeutic options? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:695-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Tarantino I, Traina M, Mocciaro F, Barresi L, Curcio G, Di Pisa M, Granata A, Volpes R, Gridelli B. Fully covered metallic stents in biliary stenosis after orthotopic liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2012;44:246-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Phillips MS, Bonatti H, Sauer BG, Smith L, Javaid M, Kahaleh M, Schmitt T. Elevated stricture rate following the use of fully covered self-expandable metal biliary stents for biliary leaks following liver transplantation. Endoscopy. 2011;43:512-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Wang AY, Ellen K, Berg CL, Schmitt TM, Kahaleh M. Fully covered self-expandable metallic stents in the management of complex biliary leaks: preliminary data - a case series. Endoscopy. 2009;41:781-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ho H, Mahajan A, Gosain S, Jain A, Brock A, Rehan ME, Ellen K, Shami VM, Kahaleh M. Management of complications associated with partially covered biliary metal stents. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:516-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Behm BW, Brock A, Clarke BW, Adams RB, Northup PG, Yeaton P, Kahaleh M. Cost analysis of temporarily placed covered self expandable metallic stents versus plastic stents in biliary strictures related to chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB211. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Rabenstein T, Schneider HT, Bulling D, Nicklas M, Katalinic A, Hahn EG, Martus P, Ell C. Analysis of the risk factors associated with endoscopic sphincterotomy techniques: preliminary results of a prospective study, with emphasis on the reduced risk of acute pancreatitis with low-dose anticoagulation treatment. Endoscopy. 2000;32:10-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Wilcox CM, Phadnis M, Varadarajulu S. Biliary stent placement is associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:546-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ, Uflacker R, Vujic I, Cotton PB. Transpapillary stenting of proximal biliary strictures: does biliary sphincterotomy reduce the risk of postprocedure pancreatitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:46-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Kobayashi N, Zhu YL S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL