Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.567

Peer-review started: October 11, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: November 29, 2014

Accepted: February 9, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Processing time: 219 Days and 4.9 Hours

A 32-year-old female presented with 5-year history of iron deficiency anemia, marked pallor and edema of both lower limbs. Laboratory investigations including complete blood count, blood film, iron studies, lipid profile, ascitic fluid analysis, test of stool for occult blood and alpha 1 anti-trypsin. Upper, lower gastrointestinal (GIT) endoscopies, and enteroscopy were performed. Imaging techniques as abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography were done. Echocardiography, lymph node biopsy and bone marrow examination were normal. The case was diagnosed as Waldmann’s disease with protein losing enteropathy and recurrent GIT bleeding. Management started with low fat diet with medium chain triglyceride, octreotide 200 μg twice a day, tranexamic acid and blood transfusion. Then, exploratory laparotomy with pathological examination of resected segment was done when recurrent GIT bleeding occurred and to excluded malignant transformation.

Core tip: To our knowledge, this is the first “Egyptian” case of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. In addition, its presentation is rare with blood loss anemia in contrast to the more common presentation with hypoproteinemia and edema. So, we are reporting a case with a rare clinical presentation of a rare disease. Double balloon enteroscopy was so beneficial in the diagnosis of the case superior to capsule endoscopy because the advantage of biopsy and histopathologic examination. There is controversy about medical treatment options, surgical treatment may be preferred in localized lesions otherwise, has no role. Prognosis may be favorable.

- Citation: El-Etreby SA, Altonbary AY, Sorogy ME, Elkashef W, Mazroa JA, Bahgat MH. Anaemia in Waldmann’s disease: A rare presentation of a rare disease. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(5): 567-572

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i5/567.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.567

Waldmann’s disease; also called primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (PIL) is a rare form of protein losing enteropathy caused by leakage of lymph inside the small intestinal lumen from dilated lacteals. The manifestations begin before the age of 30 years in 90% of cases, often in childhood. Whether bleeding into gastrointestinal tract a feature of PIL or not is still controversial. Here, we present a case of a young women with chronic blood loss anemia (iron deficiency and positive fecal occult blood test) caused by Waldmann’s disease.

A 32-year-old female with 5 year history of iron deficiency anemia was referred to our Gastroenterology Unit for further evaluation. History was irrelevant apart from easily fatigability and repeated blood transfusions as well as iron therapy. Examination revealed marked pallor and edema of both lower limbs.

Laboratory findings of a 32 years old female with Waldmann's disease are shown in Table 1.

| Test | Result | Normal reference |

| Complete blood count | ||

| Hemoglobin | 5.2 g/dL | 12-18 g/dL |

| HCT | 18.30% | 37%-51% |

| MCV | 70.2 pg | 80-97 flpg |

| MCHC | 28.4 g/dL | 31-36 g/dL |

| Platelets | 284 | 140-440 cell/cm3 |

| WBCs | 3.8 | 4.1-10.9 cell/cm3 |

| Lymphocytes | 500 | 600-1400 |

| Blood film | ||

| Hypercellular bone marrow with no blast cells | ||

| Blood chemistry | ||

| s. Albumin | 2.1 g/dL | 3.5-5 g/ dL |

| AST | 30 IU/L | Up to 40 U/L |

| ALT | 25 IU/L | Up to 45 U/L |

| s. cholesterol | 107 mg/dL | Up to 200 mg/dL |

| s. triglyceride | 54 mg/dL | Up to 160 mg/dL |

| s. iron | 23 ng/dL | 28-170 ng/dL |

| s. ferritin | 12 ng/mL | 40-430 ng/mL |

| TIBC | 750 ng/dL | 261-478 ng/dL |

| s. TSH | 1.2 mIU/L | 0.3-3.04 mIU/L |

| Stool tests | ||

| Occult blood | Positive | |

| α-1 AT clearance | 2 folds above normal range | |

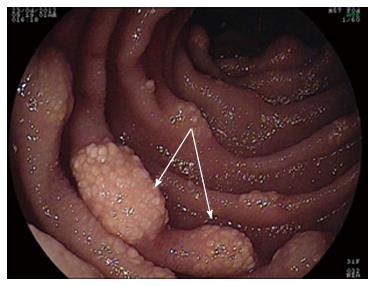

Upper and lower GI endoscopies were done twice within two-month period and did not reveal any gross pathology. So, Fujinon’s Double Balloon Endoscopy System (with 2.8 mm forceps channel) was used to examine the small bowel through oral route down to 310 cm from the ligament of Trietz. Multiple lymphangectasias (Figure 1) were seen starting at about 100 cm, extending all through the assessed parts; some of them were actively bleeding. The most affected area (at about 100 cm) was tattooed with India Ink. Histopathological examination of the lesions revealed multiple dilated vascular and lymphatic spaces and few lymphocytes with no evidence of malignancy, picture consistent with capillary telangiectasia.

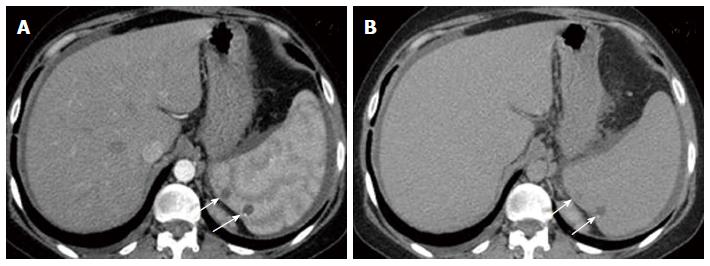

Abdominal ultrasonography, abdominal computed tomography (CT), echocardiography, inguinal lymph node biopsy, and bone marrow examination were performed to exclude secondary causes of lymphangiectasia. All tests were normal except for mild splenomegaly (due to multiple hemangiomas).

Management started with low fat diet with medium chain triglyceride, octreotide 200 μg/twice a day, tranexamic acid and blood transfusion till an acceptable level of hemoglobin was achieved (about 9 g/dL). She was discharged on diet regimen and regular follow up.

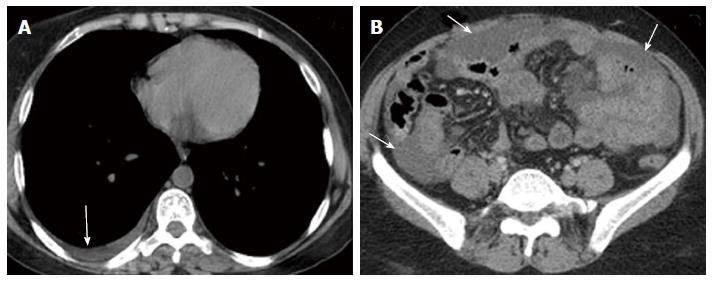

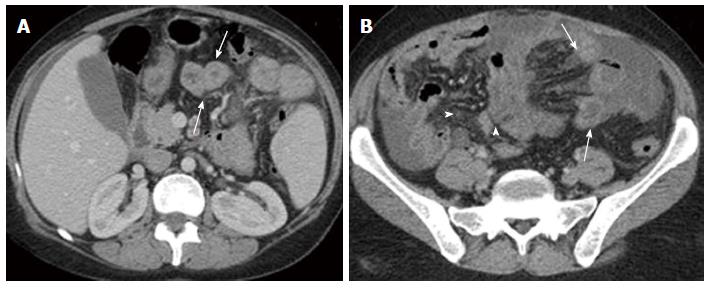

Nine months later during routine follow up, clinical examination showed marked pallor (Hb 6 g/dL) and abdominal ultrasonography revealed moderate ascites and mild right sided pleural effusion. Ascitic fluid was milky and turbid. Chemical analysis of ascitic fluid sample revealed glucose of 108 mg/dL, total protein of 1170 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase of 195 U/L, triglycerides of 1232 mg/dL (diagnostic of chylous ascites), WBCs of 250 cell/cm3 mainly lymphocytes, and RBCs of 0.01 × 106. Cytological examination of ascitic fluid revealed no atypical or malignant cells. ZN stain and adenosine deaminase were negative. Triphasic CT scan was performed by 8 multi-slice G.E. CT scanner. It revealed right pleural effusion, mild ascites; both had uncomplicated fluid density: 0-20HU (Figure 2) and multiple splenic hemangiomas (Figure 3). Regarding small intestine, CT revealed dilated small intestinal loops with diffuse, nodular wall thickening (reaching up to 9 mm), mesenteric hypodense bands representing dilated lymphatic channels and mesenteric edema (Figure 4). Neither lymphadenopathy nor hepatomegaly was detected.

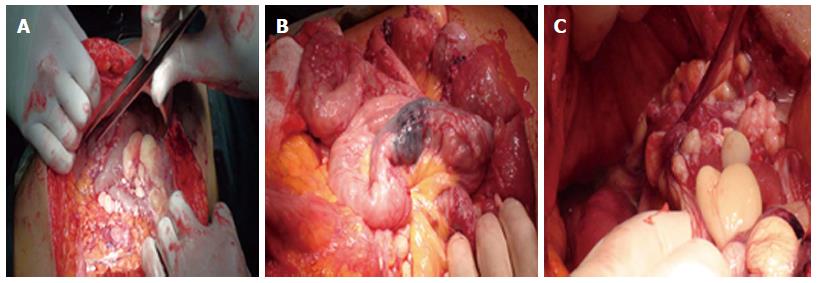

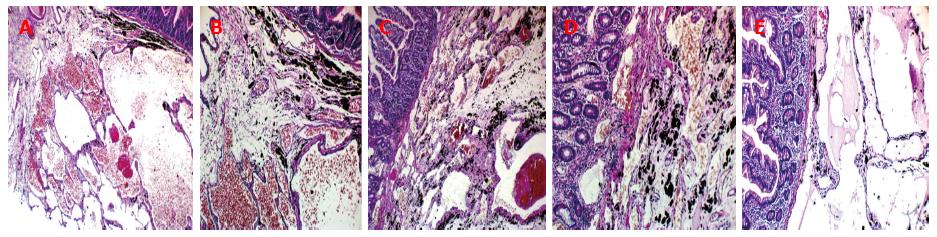

Surgical opinion was sought and malignant transformation was suspected. So, exploratory laparotomy was done through midline incision. Findings include minimal ascites, multiple cysts related to the small intestinal wall and its mesentry and a discolored segment of the proximal jejunum previously marked with India Ink by enteroscopy (Figure 5) but no masses were found. Resection anastomosis of the discolored segment was done. Histopathological examination revealed large gaping vascular spaces lined by flat endothelial cells and filled by lymph fluid, picture consistent with primary intestinal lymphangectasia (Figure 6).

Postoperative outcome was favorable and she was discharged home after 5 d.

On the 20th postoperative day, patient achieved marked improvement of her general condition, disappearance of edema lower limb, ascites, and pleural effusion. Laboratory investigations were; s. albumin 4.1 g/dL, HB 10.9 g/dL, platelets count 147 cell/cm3, WBCs 4900 cell/cm3 with normal distribution. Six months later, she remained asymptomatic with weight gain of 5 kg and rather stable hemoglobin level.

Protein losing enteropathy (PLE) is a rare cause of hypoproteinemia due to gastrointestinal (GI) loss of serum protein. This rare condition has many reported causes (Table 2) including the rare Waldmann’s disease (PIL) in which GI protein loss results from leakage of lymph through the ectatic intestinal lacteals[2].

| Erosive gastrointestinal disease |

| Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Gut malignancy |

| Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy |

| Erosive gastropathy |

| Acute graft vs host disease |

| Pseudomembranous enterocolitis |

| Ulcerative jejunoenterocolitis |

| Intestinal lymphoma |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Non erosive gastrointestinal disease |

| Celiac disease |

| Hypertrophic gastropathies |

| Eosinophilic gastroenteritis |

| Connective tissue disorders |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| Amyloidosis |

| Microscopic colitis |

| Tropical sprue |

| Whipple's disease |

| Parasitic diseases |

| Viral gastroenteritis |

| Increased interstitial pressure |

| Intestinal lymphangiectasia |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Constrictive pericarditis |

| Congenital heart diseases |

| Fontan procedure for single ventricle |

| Portal hypertensive gastroenteropathy |

| Hepatic venous outflow obstruction |

| Enteric lymphatic fistula |

| Mesenteric venous thrombosis |

| Sclerosing mesenteritis |

| Mesenteric tuberculosis or sarcoidosis |

| Neoplasia involving mesenteric lymph nodes or lymphatics |

| Chronic pancreatitis with pseudocysts |

| Congenital malformations of lymphatic |

| Retoperitoneal fibrosis |

PIL predominantly affects young children although it may also be diagnosed in older age. There is slight male preponderance with 3:2 ratio. On the other hand, race is not a predictor of PIL[3,4].

Patients usually present with bilateral lower limb edema[2-7]. Other manifestations like pain, loose motion, and malnutrition are less common[8]. Rare manifestations include abdominal mass, Mechanical ileus[9-11], chylous reflux[12,13], iron deficiency with anemia[14], necrolytic migratory erythema[15], recurrent hemolytic uremic syndrome[16], and osteomalacia[17]. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding was even more rare being reported in only 2 cases[18,19].

Work up of diagnosis consist of laboratory, imaging studies and GIT endoscopy with confirmatory histopathological examination[20].

The most common laboratory finding is hypoproteinemia. Hypo-albuminemia is most prominent and lymphopenia. Cholesterol levels are not usually elevated. PLE can be confirmed by presence of excess fecal α1-antitrypsin[21,22].

Abdominal CT scan may show dilated thickened small intestinal loops, ascites, halo sign and edematous mesentery. It also helps rule out secondary causes[23,24].

Diagnosis can only be confirmed by finding dilated lacteals both on endoscopic and histopathologic examination[25,26]. Video capsule endoscopy imaging provides the same information and allow exploration of the whole small bowel but does not allow biopsies[27].

PIL has to be differentiated from secondary causes of intestinal lymphangiectasia such as Crohn’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis, and Whipple’s disease as well as from causes of PLE without lymphangiectasia such as Mentrier’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[20].

Medical management relies on diet modification with low fat replaced by medium-chain triglycerides thus preventing fat overloading of intestinal lacteal[28,29].

Response to other medications, such as[30-31] octreotide[32-36] and steroids[37] is variable.

Small intestinal resection is indicated in localized forms of the disease[38,39].

Natural history of PIL is greatly variable; depending on involvement of intestine either generalized or localized with blockage of mesenteric lymphatic drainage. Prognosis may be favorable unless it is complicated by intestinal B-lymphoma or effusion in serous sacs[20,40].

A 32-year-old female presented with 5-year history of iron deficiency anemia, marked pallor and edema of both lower limbs.

Examination revealed marked pallor and edema of both lower limbs.

Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia has to be differentiated from secondary causes of intestinal lymphangiectasia such as Crohn’s disease, intestinal tuberculosis, and Whipple’s disease as well as from causes of protein losing enteropathy without lymphangiectasia such as Mentrier’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus.

Patient hemoglobin level and serum albumin were 5.2 g/dL, 2.1 g/dL respectively. α-1 AT clearance was 2 folds above normal range and stool test for occult blood yield positive result.

Computed tomography of the abdomen revealed dilated small intestinal loops with diffuse, nodular wall thickening, mesenteric hypodense bands representing dilated lymphatic channels and mesenteric edema.

Double balloon enteroscopy was performed, and revealed presence of multiple lymphangectasias, some of them were actively bleeding.

Histopathological examination of the lesions revealed multiple dilated vascular and lymphatic spaces and few lymphocytes with no evidence of malignancy, picture consistent with capillary telangiectasia.

Management started with low fat diet with medium chain triglyceride, octreotide 200 μg/twice a day, tranexamic acid and blood transfusion till an acceptable level of hemoglobin was achieved (about 9 g/dL). But the results was unsatisfactory.

Only two cases with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia were presented in literatures by gastrointestinal bleeding.

Chronic blood loss anemia (iron deficiency and positive fecal occult blood test) could be a one of manifestation of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia.

This case report represents a case of primary intestinal lymphangiectasia with rare presentation, recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding and iron deficiency anemia. Also, it yields our experience with different treatment modalities that could be used.

The article highlights the clinical characteristics, diagnostic modalities and treatment options available for primary intestinal lymphangiectasia.

| 1. | Greenwald D. Protein-Losing Gastroenteropathy. Sleisenger&Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 8th ed. Saunders: Philadelphia 2006; 557-563. |

| 2. | Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, Davidson JD, Gordon RS. The role of the gastrointestinal system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia”. Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Boursier V, Vignes S. Lymphangiectasiesintestinales primitives (maladie de Waldmann) révélées par unlymphoedème des membres. J Mal Vasc. 2004;29:103-106. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tift WL, Lloyd JK. Intestinal lymphangiectasia. Long-term results with MCT diet. Arch Dis Child. 1975;50:269-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Le Bougeant P, Delbrel X, Grenouillet M, Leou S, Djossou F, Beylot J, Lebras M, Longy-Boursier M. Familial Waldmann’s disease. Ann Med Interne (Paris). 2000;151:511-512. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Vardy PA, Lebenthal E, Shwachman H. Intestinal lymphagiectasia: a reappraisal. Pediatrics. 1975;55:842-851. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Goktan C, Pekindil G, Orguc S, Coskun T, Serter S. Bilateral breast edema in intestinal lymphangiectasia. Breast J. 2005;11:360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee WS, Boey CC. Chronic diarrhoea in infants and young children: causes, clinical features and outcome. J Paediatr Child Health. 1999;35:260-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rao R, Shashidhar H. Intestinal lymphangiectasia presenting as abdominal mass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:522-523, discussion 523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lobo B, Casellas F, de Torres I, Chicharro L, Malagelada JR. Usefulness of jejunal biopsy in the study of intestinal malabsorption in the elderly. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lenzhofer R, Lindner M, Moser A, Berger J, Schuschnigg C, Thurner J. Acute jejunal ileus in intestinal lymphangiectasia. Clin Investig. 1993;71:568-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | O’Driscoll JB, Chalmers RJ, Warnes TW. Chylous reflux into abdominal skin simulating lymphangioma circumscriptum in a patient with primary intestinal lymphangiectasia. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1991;16:124-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Karg E, Bereczki C, Kovacs J, Korom I, Varkonyi A, Megyeri P, Turi S. Primary lymphoedema associated with xanthomatosis, vaginal lymphorrhoea and intestinal lymphangiectasia. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:134-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Iida F, Wada R, Sato A, Yamada T. Clinicopathologic consideration of protein-losing enteropathy due to lymphangiectasia of the intestine. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;151:391-395. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Baricault S, Soubrane JC, Courville P, Young P, Joly P. [Necrolytic migratory erythema in Waldmann’s disease]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2006;133:693-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kalman S, Bakkaloğlu S, Dalgiç B, Ozkaya O, Söylemezoğlu O, Buyan N. Recurrent hemolytic uremic syndrome associated with intestinal lymphangiectasia. J Nephrol. 2007;20:246-249. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sahli H, Ben Mbarek R, Elleuch M, Azzouz D, Meddeb N, Chéour E, Azzouz MM, Sellami S. Osteomalacia in a patient with primary intestinal lymphangiectasis (Waldmann’s disease). Joint Bone Spine. 2008;75:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Herfarth H, Hofstädter F, Feuerbach S, Jürgen Schlitt H, Schölmerich J, Rogler G. A case of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding and protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4:288-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maamer AB, Baazaoui J, Zaafouri H, Soualah W, Cherif A. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia or Waldmann’s disease: a rare cause of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2012;13:97-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Vignes S, Bellanger J. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia (Waldmann’s disease). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2008;3:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 21. | Karbach U, Ewe K, Bodenstein H. Alpha 1-antitrypsin, a reliable endogenous marker for intestinal protein loss and its application in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut. 1983;24:718-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Strygler B, Nicar MJ, Santangelo WC, Porter JL, Fordtran JS. Alpha 1-antitrypsin excretion in stool in normal subjects and in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1380-1387. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Holzknecht N, Helmberger T, Beuers U, Rust C, Wiebecke B, Reiser M. Cross-sectional imaging findings in congenital intestinal lymphangiectasia. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:526-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hashemi J, Farhoodi M, Farrokh D, Pishva A. Congenital Intestinal Lymphangiectasia: Report of a Case. I. ran J Radiol. 2008;5:189. |

| 25. | Waldmann TA. Protein -losing gastroenteropathies. Bockus gastroenterology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985; 1814-1837. |

| 26. | Kazemi F, Lemann M, Modigliani R. Interet des explorations digestives invasives pour le diagnostic des lymphangiectasiesintestinales primitives. Gastroenterology cliniquesetbiologique. 2001;25:0399-8320. |

| 27. | Oh TG, Chung JW, Kim HM, Han SJ, Lee JS, Park JY, Song SY. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia diagnosed by capsule endoscopy and double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alfano V, Tritto G, Alfonsi L, Cella A, Pasanisi F, Contaldo F. Stable reversal of pathologic signs of primitive intestinal lymphangiectasia with a hypolipidic, MCT-enriched diet. Nutrition. 2000;16:303-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Aoyagi K, Iida M, Matsumoto T, Sakisaka S. Enteral nutrition as a primary therapy for intestinal lymphangiectasia: value of elemental diet and polymeric diet compared with total parenteral nutrition. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1467-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mine K, Matsubayashi S, Nakai Y, Nakagawa T. Intestinal lymphangiectasia markedly improved with antiplasmin therapy. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1596-1599. [PubMed] |

| 31. | MacLean JE, Cohen E, Weinstein M. Primary intestinal and thoracic lymphangiectasia: a response to antiplasmin therapy. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1177-1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ballinger AB, Farthing MJ. Octreotide in the treatment of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;10:699-702. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Kuroiwa G, Takayama T, Sato Y, Takahashi Y, Fujita T, Nobuoka A, Kukitsu T, Kato J, Sakamaki S, Niitsu Y. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia successfully treated with octreotide. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Klingenberg RD, Homann N, Ludwig D. Type I intestinal lymphangiectasia treated successfully with slow-release octreotide. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1506-1509. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Reichlin S. Somatostatin. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:1495-1501. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Nakabayashi H, Sagara H, Usukura N, Yoshimitsu K, Imamura T, Seta T, Yanase E, Kawato M, Hiraiwa Y, Sakato S. Effect of somatostatin on the flow rate and triglyceride levels of thoracic duct lymph in normal and vagotomized dogs. Diabetes. 1981;30:440-445. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fleisher TA, Strober W, Muchmore AV, Broder S, Krawitt EL, Waldmann TA. Corticosteroid-responsive intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to an inflammatory process. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:605-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Warshaw AL, Waldmann TA, Laster L. Protein-losing enteropathy and malabsorption in regional enteritis: cure by limited ileal resection. Ann Surg. 1973;178:578-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Chen CP, Chao Y, Li CP, Lo WC, Wu CW, Tsay SH, Lee RC, Chang FY. Surgical resection of duodenal lymphangiectasia: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2880-2882. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Lymphoedema Framework: Best practice for the management of lymphoedema. International consensus. London: MEP Ltd 2006; . |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Bilir C, Chow KW, Kurtoglu E S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL