Published online May 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.532

Peer-review started: November 2, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: January 1, 2015

Accepted: January 18, 2015

Article in press: January 20, 2015

Published online: May 16, 2015

Processing time: 200 Days and 9.2 Hours

Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists (β-blockers) have been well established for use in portal hypertension for more than three decades. Different Non-selective β-blockers like propranolol, nadolol, timolol, atenolol, metoprolol and carvedilol have been in clinical practice in patients with cirrhosis. Carvedilol has proven 2-4 times more potent than propranolol as a beta-receptor blocker in trials conducted testing its efficacy for heart failure. Whether the same effect extends to its potency in the reduction of portal venous pressures is a topic of on-going debate. The aim of this review is to compare the hemodynamic and clinical effects of carvedilol with propranolol, and attempt assess whether carvedilol can be used instead of propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Carvedilol is a promising agent among the beta blockers of recent time that has shown significant effects in portal hypertension hemodynamics. It has also demonstrated an effective profile in its clinical application specifically for the prevention of variceal bleeding. Carvedilol has more potent desired physiological effects when compared to Propranolol. However, it is uncertain at the present juncture whether the improvement in hemodynamics also translates into a decreased rate of disease progression and complications when compared to propranolol. Currently Carvedilol shows promise as a therapy for portal hypertension but more clinical trials need to be carried out before we can consider it as a superior option and a replacement for propranolol.

Core tip: Carvedilol is a promising agent among the beta blockers of recent time that has shown significant effects in portal hypertension hemodynamics. For primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, the effects of carvedilol were compared to band ligation in a few trials and showed some promise, but there has been no comparison with propranolol. Patients not responding to propranolol have shown clinical response to carvedilol, opening a new window of clinical application. For secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, carvedilol has been shown to be effective. However no head-to-head trials comparing propranolol and carvedilol for variceal re-bleeding were found in literature.

- Citation: Abid S, Ali S, Baig MA, Waheed AA. Is it time to replace propranolol with carvedilol for portal hypertension? World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(5): 532-539

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i5/532.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i5.532

Liver cirrhosis remains the 12th leading cause of death worldwide according to estimates by the Global Burden of Disease Study[1]. Portal hypertension is an inevitable consequence of cirrhosis and underlies most of its complications like: variceal bleeding, ascites and hepatic encephalopathy[2]. Portal hypertension is characterised by a pathologic increase in the portal pressure gradient (the pressure difference between the portal vein and the hepatic veins) y greater than 5 mmHg. This causes the creation of porto-systemic collaterals leading to shunting of portal blood to the systemic circulation, bypassing the liver parenchyma. It has been shown that therapeutic reduction in portal pressure has been shown to improve clinical outcomes and reduces the incidence of recurrent haemorrhage, ascites, encephalopathy, and death[3-5].

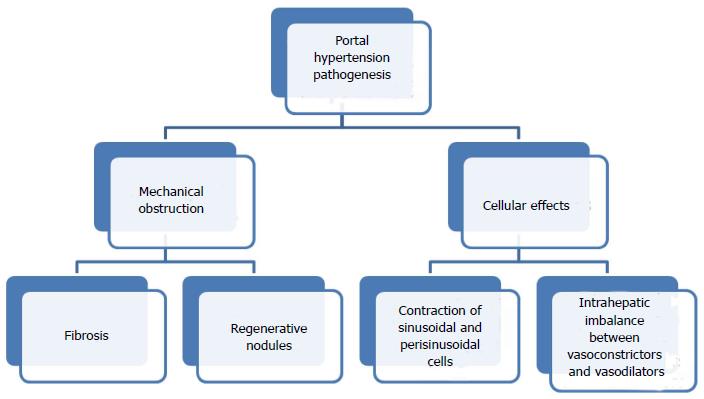

Beta-adrenergic receptor antagonists (β-blockers) have been well established for use in portal hypertension for more than three decades. Non-selective β-blockers (NSBB) have been widely utilized since 1980, when the first article on their role in portal hypertension was published by Lebrec et al[6]. Portal hypertension results from fibrosis or regenerative nodules in the liver parenchyma increasing resistance to flow and causing mechanical obstruction; contraction of sinusoidal and perisinusoidal contractile cells (stellate cells and vascular smooth muscle cells) with intrahepatic imbalance between vasoconstrictors (such as endothelin 1 and angiotensin) and vasodilators; and splanchnic vasodilatation in secondary to a relatively ischemic liver or extrahepatic excess of NO, with sGC-PKG signalling and smooth muscle cell relaxation[7] (Figure 1).

NSBB have a dual mode of action decrease portal pressure, i.e., reduction of cardiac output and splanchnic blood flow by β-1 receptor blockade, and β-2 receptor blockade, resulting in splanchnic vasoconstriction caused by unopposed effect of alpha 1 receptors[7]. NSBBs have been proven to decrease incidence of bleeding (primary prophylaxis) and re-bleeding (secondary prophylaxis) from esophageal varices[8-11]. It has been demonstrated that they also prevent bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy and development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[4,12,13]. Due to their widely diverse effects in patients with cirrhosis and widespread use, they have been dubbed as “aspirin” in clinical hepatology[14].

Different NSBBs like propranolol, nadolol, timolol, atenolol, metoprolol and carvedilol have been in clinical practice in patients with cirrhosis. Propranolol was the first, most widely studied NSBB and mainstream for treatment of portal hypertension. Carvedilol is a nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti-alpha1-adrenergic activity. It has been a relatively newer addition to the NSBBs, in the arena of portal hypertension and has demonstrated promising results in terms of clinical outcomes.

Carvedilol has proven 2-4 times more potent than propranolol as a beta-receptor blocker in trials conducted testing its efficacy for heart failure[15]. Whether the same effect extends to its potency in the reduction of portal venous pressures is a topic of ongoing debate.

The aim of this article is to compare the hemodynamic and clinical effects of carvedilol with propranolol, and attempt assess whether carvedilol can be used instead of propranolol in patients with cirrhosis.

To achieve successful protection against gastrointestinal bleeding, the portal pressure [usually measured as the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG)] has to be decreased to ≤ 12 mmHg or by 20% of baseline values[16]. Long-term follow-up of cirrhotic on beta blockers has shown that decrease of HVPG of above mentioned values results in lesser risk of developing variceal bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatorenal syndrome and hepatic encephalopathy[4].

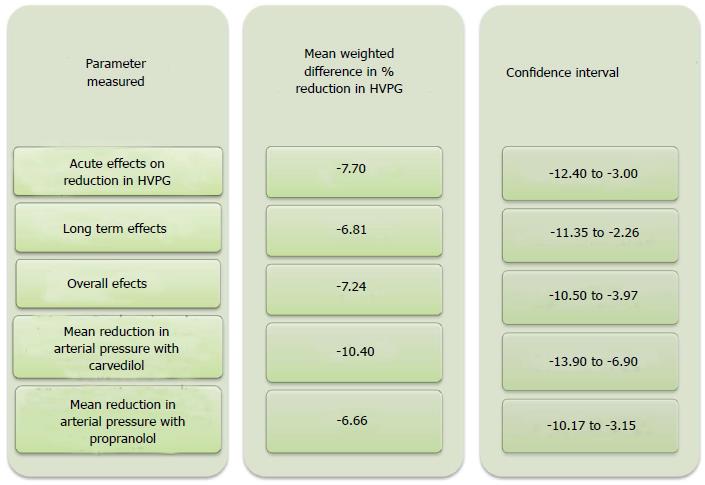

Comparison of carvedilol to propranolol for portal hypertension was made in a recent systematic review with meta-analysis which included five head-to-head randomised trials[17-22]. This analysis favored carvedilol against propranolol, in terms of: (1) acute effects on reduction in HVPG [mean weighted difference in % of reduction in hepatic vein pressure gradient; -7.70 (95%CI: -12.40--3.00)]; (2) long term effects [mean weighted difference in % of reduction in hepatic vein pressure gradient was -6.81 (95%CI: -11.35--2.26)]; and (3) overall effects [(mean weighted difference in % of reduction in hepatic vein pressure gradient -7.24 (95%CI: -10.50--3.97)].

Additionally the same metaanalysis showed that Carvedilol had a lower relative risk of failure to achieve hemodynamic response than propranolol. The number of patients who achieved a reduction in HVPG to ≥ 20% or to ≤ 12 mmHg was reported in 4 of the 5 studies and was also markedly higher with carvedilol vs propranolol (57/94 vs 33/87). However, this favourable difference for carvedilol did not reach statistical significance.

Carvedilol caused more reduction in arterial blood pressure resulting in orthostatic hypotension as compared to propranolol. Propranolol caused a - 6.66 mmHg (95%CI: -10.17--3.15) mean reduction in arterial pressure whereas carvedilol caused a mean reduction of -10.40 (95%CI: -13.9--6.9). The reduction in mean arterial pressure was found to be significant with both drugs, but the degree of reduction was in the order of one-third more with carvedilol compared to propranolol[17] (Figure 2).

Therefore carvedilol has been shown to be superior to propranolol in causing of acute, long-term and overall reduction of the hepatic venous pressure gradient, i.e., portal venous pressure. The proportion of patients who demonstrated an adequate response is also higher for carvedilol.

Although the translation of these effects in terms of clinical benefit of reduced gastrointestinal bleeding events is significant, these changes in hemodynamic parameters come at the cost of orthostatic hypotension and fluid retention including ascites, with the use of carvedilol. However carvedilol can be a safe alternative in patients who are not hypotensive. In addition carvedilol has achieved significant hemodynamic response in more than half of the patients who were resistant to propranolol[23].

Pre-primary prophylaxis: Prevention of development of varices in patients with portal hypertension is known as pre-primary prophylaxis. Experimental models of portal hypertension have shown that B-Blockers delay the development of collaterals[24,25]. Escorsell et al[26] demonstrated that administration of β-blockers (timolol) to patients without varices caused a greater reduction in portal pressure than the reduction seen in patients with varices[26]. However this effect of use of timolol did not translate into prevention of variceal formation and variceal hemorrhage in a randomised study by Groszmann et al[27] which compared timolol with placebo in patients without varices. The study by Calés et al[28] using propranolol, for pre-primary prophylaxis did not show clinical benefit in terms of variceal development. To-date there were no studies using carvedilol for pre-primary prophylaxis.

Due to lack of any demonstrated clinical benefits of β-blockers in patients with portal hypertension without varices and adverse effects of these medications, none of the current guidelines (including Baveno V consensus[2], AASLD[29], and EASL/AASLD consensus[30]) recommend their use for pre-primary prophylaxis.

Primary prophylaxis: NSBB are recommended for use in primary prevention of variceal bleeding, as they have been associated with decrease in incidence of first bleeding episode and mortality benefits[2].

A meta-analysis of published randomised controlled trials on primary prophylaxis including 1859 patients, revealed pooled risk difference of 11% in incidence of variceal bleeding with use of propranolol against controls[31]. In another meta-analysis, D’Amico et al[32] demonstrated that in patients with varices of any size, β-blockers reduced the risk of a first bleeding episode from 25% to 15% within 2 years. The absolute risk difference was 9% (15% vs 24%) as compared to placebo. Moreover, the absolute risk reduction in mortality was found to be 4% (from 27% to 23%)[32].

Another meta-analyses has reported the usage of Beta blockers as primary prophylaxis to be associated with a 40% reduction in bleeding risk and a trend towards improved survival[33]. In a double-blind randomised trial, the Boston-New Haven-Barcelona Portal Hypertension Study Group compared propranolol with placebo for primary prophylaxis. There was significant difference in incidence of bleeding between the study groups favouring propranolol (incidence of bleeding 4% vs 22%; P≤ 0.01) during a mean follow-up of 16 mo. However there was no difference in mortality rates between the two groups[34].

Propranolol has been compared to esophageal band ligation (EBL) in terms of bleeding prevention and mortality reduction in patients with cirrhosis in several randomised controlled trials. A meta-analysis of sixteen randomised controlled trials found EBL causing significant reduction of the risk of first variceal bleeding compared to propranolol (relative risk difference 9.2%, 95%CI: 5.2%-13.1%, and POR 0.5, 95%CI: 0.37–0.68). However there was no statistically significant difference in Mortality between the two groups (POR 0.94, 95%CI: 0.70-1.28). On average, 3 endoscopic sessions were required to eradicate varices and at least 33 endoscopic procedures were needed to prevent one bleeding episode as compared with NSBBs[35]. However as NSBB are cheap, as haemodynamic monitoring is not required[36].

In a randomized control trial, Carvedilol has been compared with EBL and showed a significantly lower rate of first variceal bleeding (with minor adverse effects) in patients taking carvedilol 12.5 mg daily compared with EBL (10% vs 23%, HR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.19-0.96)[37]. The lowest dose of carvedilol tested in this trial was 12.5 mg, which is known to cause a smaller reduction in HVPG than to actually cause prevention of first bleeding episode. So the results of this study need to be interpreted after considering its limitations[38].

Another randomised controlled trial by Shah et al[39] reported that both EBL and carvedilol groups had comparable variceal bleeding rates (8.5% vs 6.9%), bleeding related mortality (4.6% vs 4.9%) and overall mortality (12.8% vs 19.5%) respectively[39]. Although the study was underpowered, the authors suspect that carvedilol is not superior to EBL for primary prophylaxis of varices.

Use of carvedilol has been found to cause reduction of HVPG in patients failing to respond to propranolol, thus leading to lesser bleeding episodes in this group of patients. Bleeding rates followed up for 2 years were 11% with propranolol vs 5% with carvedilol and 25% with EBL (P = 0.0429)[23]. We did not find any studies comparing propranolol with carvedilol head-to-head for primary prevention.

Secondary prophylaxis: Secondary prophylaxis is prevention of recurrence after index variceal bleeding episode. The 1-year mortality after an episode of variceal bleeding is 40%[11]. Variceal bleeding recurs in 60% at 1-year with 6-wk mortality of 20% for every re-bleeding episode[2]. NSBBs have been widely used for prevention of re-bleeding and have been shown to decrease the rate of re-bleeding from varices to 42%, as compared to 63% in controls in several meta-analyses[32]. In addition these agents decrease overall mortality from 27% to 20%, and bleeding related mortality[40].

Carvedilol was compared with combination of nadolol and isosorbide-5-mononitrate in a randomized controlled trial in patients who previously had variceal bleeding. This study demonstrated that after a follow-up of 30 mo there was no significant difference in incidence of recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding between carvedilol and combination groups (62% vs 61%; P = 0.90). There was no significant difference between the Rate of recurrence of variceal bleeding between the carvedilol and combination groups (51% vs 43%; P = 0.46)[41]. Interim analysis of a multicentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with endoscopic band ligation for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding, demonstrated no significant difference between the groups in re-bleeding rates (37.5% vs 29%; P = 0.72). However the patients in carvedilol group had lower 1-year mortality rates as compared to EBL group (25% vs 51.6%; P = 0.058)[42].

The pioneer trial by Pagliaro et al[8] demonstrated that propranolol was effective in decreasing the incidence of variceal re-bleeding when compared to controls. A comprehensive meta-analysis of 12 randomised controlled trials for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding showed that, use of β-blockers (11 using propranolol) was associated with increase in mean percentage of patients with no re-bleeding (21% mean improvement rate, 95%CI: 10%-32%, P < 0.001), the mean percentage of patients with no variceal re-bleeding (20% mean improvement rate, 95%CI: 11%-28%, P < 0.001), the mean survival rate (5.4% mean improvement rate, 95%CI: 0%-11%, P < 0.05, RR = 1.27), the mean percentage of patients free of bleeding death (7.4%, 95%CI: 2%-13%, P < 0.01, RR = 1.50)[40].

Baveno V consensus guidelines recommend a combination of β-blockers and variceal band ligation as the preferred therapy for secondary prophylaxis because it results in lower re-bleeding rates compared to either therapy alone[2]. Ahmad et al[43] compared combination of EBL and propranolol against propranolol for secondary prevention and found no statistical difference in re-bleeding (22% vs 38%) and mortality rates (23% vs 19%) between the groups. However the incidence of re-bleeding was higher in patients on propranolol alone[43].

Propranolol retains its place as the most widely used and studied drug for secondary prophylaxis with clear benefits as compared to placebo and combination with EBL. The evidence for carvedilol in variceal rebleeding recurrence is minimal but promising.

Described as mosaic, snake-skin-like appearance of gastric mucosa with or without red punctuate erythema, portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) is estimated to be present in up to 80% of cirrhotic patients[44]. PHG can cause acute bleeding rarely with an incidence of 3% in three years, and in 2.5%-30% patients it may result in chronic insidious bleeding[45,46].

NSBBs have been shown to lower the incidence of bleeding in acute and chronic forms of haemorrhage from PHG. One of the earliest randomised controlled trials using propranolol showed lower haemorrhage rates, increase in haemoglobin level and an apparent improvement in the endoscopic appearance of the lesion when compared to placebo[47]. Pérez-Ayuso et al[12], in a randomised trial of used propranolol against no therapy in patients for secondary prophylaxis of bleeding from PHG. The study demonstrated higher number of patients remaining free of bleeding with propranolol in acute (85% vs 20%) and chronic setting (69% vs 30% at 30 mo). On multivariate analysis, the sole independent predictor of recurrent haemorrhage was the absence of propranolol[12].

Although the use of β-blockers for PHG is widespread, based upon current evidence strong recommendations can’t be made for NSBB for this indication. We also did not find any studies using carvedilol to control bleeding from portal gastropathy.

NSBBs have been shown to have preventive effect on development of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in a meta-analysis by Senzolo et al[13]. This analysis included three randomised controlled trials and two retrospective studies all using propranolol for prophylaxis of variceal bleeding, with respect to the incidence of SBP. Statistically significant difference of 12.1% (P < 0.001) was found in favour of propranolol in prevention of SBP.

A recently published thorough retrospective analysis of data from 607 patients with cirrhosis by Mandorfer et al[48] demonstrated no difference in incidence of SBP between NSBB users and patients who did not. Occurrence rates of SBP were similar between patients with and without NSBB treatment. However, NSBB use was associated with higher transplant-free survival in patients without SBP and reduced hospitalization rates[48].

In contrast, Mandorfer et al[48] demonstrated that in patients who have developed SBP, NSBB were associated with hemodynamic compromise and decreased blood pressures, reduced transplant free survival, increased hospitalization rates, and increased incidence of the hepatorenal syndrome and acute kidney injury. In another study, using a NSBB (propranolol) in patients with refractory ascites was found to reduce 1-year survival against those not using this drug (median survival: 5 mo vs 20 mo respectively)[49]. These results advocate against the use of NSBB in patients with advanced cirrhosis with ascites and SBP.

To conclude, the current evidence is variable about the role of NSBB in decreasing the incidence of SBP. However they can increase transplant-free survival in patients without SBP. In cases of advanced cirrhosis with ascites and the patients who have developed SBP, their use proves detrimental causing higher rates of hemodynamic compromise, time of hospitalization and risks of renal dysfunction. All the studies on NSBB use for SBP have used propranolol. We did not find any study about the use of carvedilol in patients with advanced cirrhosis and SBP, nor a head-to-head comparison of propranolol and carvedilol in this regard.

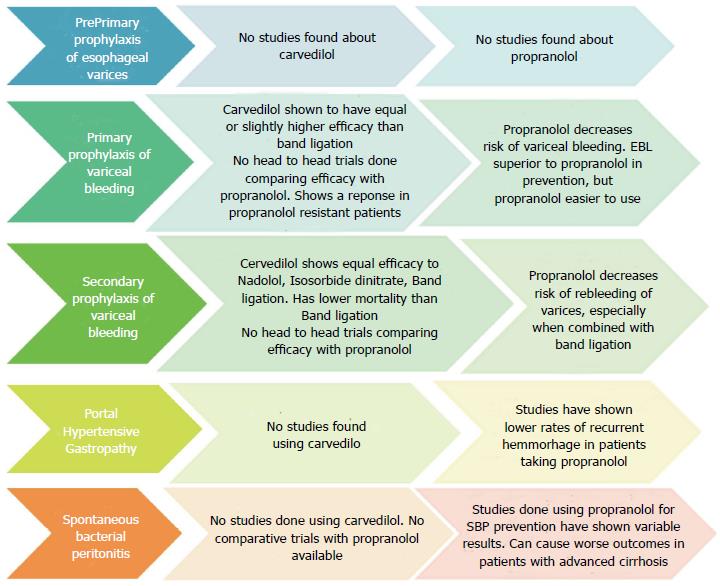

After reviewing the existing literature, it seems that Carvedilol has more potent desired physiological effects when compared to Propranolol. However, it is uncertain at the present juncture whether the improvement in hemodynamics also translates into a decreased rate of disease progression and complications when compared to propranolol (Figure 3).

There have been no clinical trials comparing carvedilol and propranolol for pre-primary prophylaxis. For Primary prophylaxis, the effects of Carvedilol have been compared to Endoscopic band ligation in a few trials and show some promise, but there has been no head to head comparison with propranolol. However, patients not responding to propranolol have shown clinical response to Carvedilol, opening a new window of clinical application.

For secondary prophylaxis, carvedilol has been compared to Beta blockers other than propranolol and Endoscopic Band Ligation, and seems to be equally effective. However, the most effective therapy to date remains a combination of Endoscopic Band Ligation, and no head to head trials have been conducted comparing carvedilol with propranolol. Similarly, there have been no trials exploring the role of carvedilol in portal hypertensive gastropathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis.

Thus, currently Carvedilol shows promise as a therapy for portal hypertension but more clinical trials need to be carried out before we can consider it as a superior option and a replacement for propranolol.

| 1. | Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095-2128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9500] [Cited by in RCA: 9741] [Article Influence: 695.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1066] [Cited by in RCA: 1047] [Article Influence: 65.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Feu F, Bordas JM, Luca A, García-Pagán JC, Escorsell A, Bosch J, Rodés J. Reduction of variceal pressure by propranolol: comparison of the effects on portal pressure and azygos blood flow in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1993;18:1082-1089. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Abraldes JG, Tarantino I, Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Rodés J, Bosch J. Hemodynamic response to pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension and long-term prognosis of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2003;37:902-908. [PubMed] |

| 5. | D’Amico G, Garcia-Pagan JC, Luca A, Bosch J. Hepatic vein pressure gradient reduction and prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1611-1624. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lebrec D, Nouel O, Corbic M, Benhamou JP. Propranolol--a medical treatment for portal hypertension? Lancet. 1980;2:180-182. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tripathi D, Hayes PC. Beta-blockers in portal hypertension: new developments and controversies. Liver Int. 2014;34:655-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pagliaro L. Lebrec D, Poynard T, Hillon P, Benhamou J-P. Propranolol for prevention of recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. A controlled study [N Engl J Med 1981; 305: 1371-1374]. J Hepatol. 2002;36:148-150. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pascal JP, Cales P. Propranolol in the prevention of first upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:856-861. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Poynard T, Calès P, Pasta L, Ideo G, Pascal JP, Pagliaro L, Lebrec D. Beta-adrenergic-antagonist drugs in the prevention of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis and esophageal varices. An analysis of data and prognostic factors in 589 patients from four randomized clinical trials. Franco-Italian Multicenter Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1532-1538. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 639] [Cited by in RCA: 649] [Article Influence: 40.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pérez-Ayuso RM, Piqué JM, Bosch J, Panés J, González A, Pérez R, Rigau J, Quintero E, Valderrama R, Viver J. Propranolol in prevention of recurrent bleeding from severe portal hypertensive gastropathy in cirrhosis. Lancet. 1991;337:1431-1434. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Senzolo M, Cholongitas E, Burra P, Leandro G, Thalheimer U, Patch D, Burroughs AK. beta-Blockers protect against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: a meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2009;29:1189-1193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Triantos C, Samonakis D, Thalheimer U, Patch D, Burroughs A. The relationship between liver function and portal pressure: what comes first, the chicken or the egg? J Hepatol. 2005;42:146-147; author reply 147-148. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Frishman WH. Carvedilol. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1759-1765. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Feu F, García-Pagán JC, Bosch J, Luca A, Terés J, Escorsell A, Rodés J. Relation between portal pressure response to pharmacotherapy and risk of recurrent variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Lancet. 1995;346:1056-1059. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sinagra E, Perricone G, D’Amico M, Tinè F, D’Amico G. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the haemodynamic effects of carvedilol compared with propranolol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bañares R, Moitinho E, Piqueras B, Casado M, García-Pagán JC, de Diego A, Bosch J. Carvedilol, a new nonselective beta-blocker with intrinsic anti- Alpha1-adrenergic activity, has a greater portal hypotensive effect than propranolol in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;30:79-83. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Bañares R, Moitinho E, Matilla A, García-Pagán JC, Lampreave JL, Piera C, Abraldes JG, De Diego A, Albillos A, Bosch J. Randomized comparison of long-term carvedilol and propranolol administration in the treatment of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;36:1367-1373. [PubMed] |

| 20. | De BK, Das D, Sen S, Biswas PK, Mandal SK, Majumdar D, Maity AK. Acute and 7-day portal pressure response to carvedilol and propranolol in cirrhotics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:183-189. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lin HC, Yang YY, Hou MC, Huang YT, Lee FY, Lee SD. Acute administration of carvedilol is more effective than propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate in the reduction of portal pressure in patients with viral cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1953-1958. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hobolth L, Møller S, Grønbæk H, Roelsgaard K, Bendtsen F, Feldager Hansen E. Carvedilol or propranolol in portal hypertension? A randomized comparison. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47:467-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Reiberger T, Ulbrich G, Ferlitsch A, Payer BA, Schwabl P, Pinter M, Heinisch BB, Trauner M, Kramer L, Peck-Radosavljevic M. Carvedilol for primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with haemodynamic non-response to propranolol. Gut. 2013;62:1634-1641. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Lin HC, Soubrane O, Cailmail S, Lebrec D. Early chronic administration of propranolol reduces the severity of portal hypertension and portal-systemic shunts in conscious portal vein stenosed rats. J Hepatol. 1991;13:213-219. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Sarin SK, Groszmann RJ, Mosca PG, Rojkind M, Stadecker MJ, Bhatnagar R, Reuben A, Dayal Y. Propranolol ameliorates the development of portal-systemic shunting in a chronic murine schistosomiasis model of portal hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:1032-1036. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Escorsell A, Ferayorni L, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, García-Tsao G, Grace ND, Rodés J, Groszmann RJ. The portal pressure response to beta-blockade is greater in cirrhotic patients without varices than in those with varices. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:2012-2016. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Grace ND, Burroughs AK, Planas R, Escorsell A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Patch D, Matloff DS. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2254-2261. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Calés P, Oberti F, Payen JL, Naveau S, Guyader D, Blanc P, Abergel A, Bichard P, Raymond JM, Canva-Delcambre V. Lack of effect of propranolol in the prevention of large oesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis: a randomized trial. French-Speaking Club for the Study of Portal Hypertension. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:741-745. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, Groszmann RJ. Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding--unresolved issues. Summary of an American Association for the study of liver diseases and European Association for the study of the liver single-topic conference. Hepatology. 2008;47:1764-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Cheng JW, Zhu L, Gu MJ, Song ZM. Meta analysis of propranolol effects on gastrointestinal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1836-1839. [PubMed] |

| 32. | D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. Pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension: an evidence-based approach. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:475-505. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Teran JC, Imperiale TF, Mullen KD, Tavill AS, McCullough AJ. Primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:473-482. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Conn HO, Grace ND, Bosch J, Groszmann RJ, Rodés J, Wright SC, Matloff DS, Garcia-Tsao G, Fisher RL, Navasa M. Propranolol in the prevention of the first hemorrhage from esophagogastric varices: A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. The Boston-New Haven-Barcelona Portal Hypertension Study Group. Hepatology. 1991;13:902-912. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Burroughs AK, Tsochatzis EA, Triantos C. Primary prevention of variceal haemorrhage: a pharmacological approach. J Hepatol. 2010;52:946-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Triantos CK, Nikolopoulou V, Burroughs AK. Review article: the therapeutic and prognostic benefit of portal pressure reduction in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:943-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tripathi D, Ferguson JW, Kochar N, Leithead JA, Therapondos G, McAvoy NC, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Hislop WS, Mills PR. Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology. 2009;50:825-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Tsochatzis EA, Triantos CK, Burroughs AK. Gastrointestinal bleeding: Carvedilol-the best beta-blocker for primary prophylaxis? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:692-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Shah HA, Azam Z, Rauf J, Abid S, Hamid S, Jafri W, Khalid A, Ismail FW, Parkash O, Subhan A. Carvedilol vs. esophageal variceal band ligation in the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2014;60:757-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Bernard B, Lebrec D, Mathurin P, Opolon P, Poynard T. Beta-adrenergic antagonists in the prevention of gastrointestinal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1997;25:63-70. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Lo GH, Chen WC, Wang HM, Yu HC. Randomized, controlled trial of carvedilol versus nadolol plus isosorbide mononitrate for the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1681-1687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stanley AJ, Dickson S, Hayes PC, Forrest EH, Mills PR, Tripathi D, Leithead JA, MacBeth K, Smith L, Gaya DR. Multicentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with variceal band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1014-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ahmad I, Khan AA, Alam A, Butt AK, Shafqat F, Sarwar S. Propranolol, isosorbide mononitrate and endoscopic band ligation - alone or in varying combinations for the prevention of esophageal variceal rebleeding. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2009;19:283-286. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P, Battaglia G, Carta A, Prada A, Cestari R, Angeli P, Gatta A, Rossi A. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. The New Italian Endoscopic Club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC). Gastroenterology. 2000;119:181-187. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Sarin SK, Shahi HM, Jain M, Jain AK, Issar SK, Murthy NS. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy: influence of variceal eradication. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2888-2893. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, Gentili F, Attili AF, Riggio O. The natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis and mild portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1959-1965. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Hosking SW. Congestive gastropathy in portal hypertension: variations in prevalence. Hepatology. 1989;10:257-258. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Mandorfer M, Bota S, Schwabl P, Bucsics T, Pfisterer N, Kruzik M, Hagmann M, Blacky A, Ferlitsch A, Sieghart W. Nonselective β blockers increase risk for hepatorenal syndrome and death in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1680-1690.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 49. | Sersté T, Melot C, Francoz C, Durand F, Rautou PE, Valla D, Moreau R, Lebrec D. Deleterious effects of beta-blockers on survival in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites. Hepatology. 2010;52:1017-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Sciarra A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL