Published online Feb 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i2.154

Peer-review started: October 12, 2014

First decision: December 12, 2014

Revised: December 22, 2014

Accepted: January 9, 2015

Article in press: January 12, 2015

Published online: February 16, 2015

Processing time: 133 Days and 0.9 Hours

Epidermolysis bullosa is a group of genetic disorders with an autosomal dominant or an autosomal recessive mode of inheritance and more than 300 mutations. The disorder is characterized by blistering mucocutaneous lesions and has several varying phenotypes due to anchoring defect between the epidermis and dermis. The variation in phenotypic expression depends on the involved structural protein that mediates cell adherence between different layers of the skin. Epidermolysis bullosa can also involve extra-cutaneous sites including eye, nose, ear, upper airway, genitourinary tract and gastrointestinal tract. The most prominent feature of the gastrointestinal tract involvement is development of esophageal stricture. The stricture results from recurrent esophageal mucosal blistering with consequent scarring and most commonly involves the upper esophagus. Here we present a case of a young boy with dominant subtype of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa who presented with dysphagia, extensive skin blistering and missing nails. Management of an esophageal stricture eventually requires dilatation of the stricture or placement of a gastrostomy tube to keep up with the nutritional requirements. Gastrostomy tube also provides access for esophageal stricture dilatation in cases where antegrade approach through the mouth has failed.

Core tip: Epidermolysis bullosa is a genetic disorder with four main types. The most prominent feature of the disease is extensive skin blisters. Extra-cutaneous manifestations like dysphagia vary among different subtypes. Recessive type of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is the subtype most commonly associated with esophageal strictures. Treatment of dysphagia secondary to esophageal stricture involves changing diet texture, dilatation of the stricture and placement of a gastrostomy tube.

- Citation: Makker J, Bajantri B, Remy P. Rare case of dysphagia, skin blistering, missing nails in a young boy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(2): 154-158

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i2/154.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i2.154

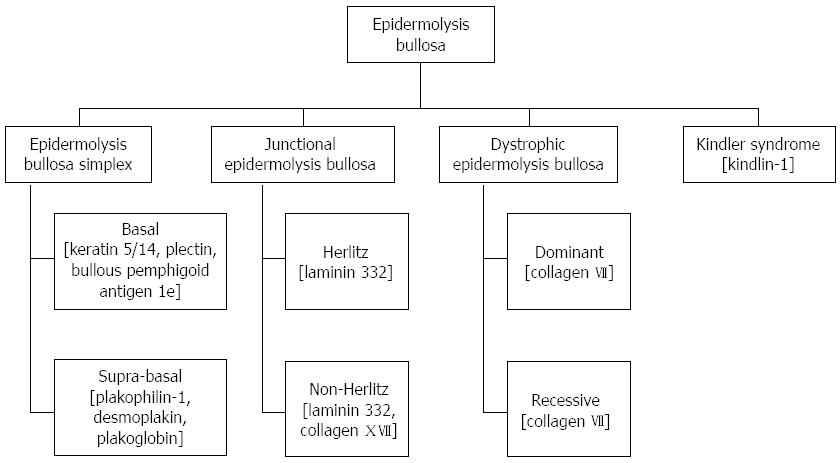

Epidermolysis bullosa is a multisystem inherited disorder with extensive skin blistering as the most prominent feature. Four distinct types of epidermolysis bullosa recognized are epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS), junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB), dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) and kindler syndrome. Severity and extent of cutaneous and extra-cutaneous features can vary among different subtypes and depends on the type of skin structural protein affected.

A 15-year-old boy with blistering skin disease since birth presented to this hospital complaining of worsening dysphagia for 3 d. He had been generally well till the age of 9 years when he started experiencing dysphagia. He described his symptoms as gradually worsening difficulty in swallowing solids for past 6 years. He mostly consumed liquids and soft consistency meals during these years. He reported an episode of worsening swallowing difficulty with inability to swallow liquids as well about 6 mo prior to presentation. At that time, he was admitted to another hospital and a barium esophagogram was obtained which showed upper esophageal stenosis. He also reported a failed endoscopic attempt at that time. Subsequently, he improved spontaneously in 2-3 d and resumed his liquid diet until 3 d ago when he again experienced difficulty swallowing liquids and solids both. He described his symptoms as inability to swallow and the food being stuck in his throat. He also claimed to have a choking sensation when he tried to drink milk. He denied chest pain, shortness of breath, fever and drooling of saliva. He denied any worsening of his skin condition.

He had an extensive skin blistering disease since birth and was advised by his pediatric dermatologist to use a moisturizing cream on the raw skin areas exposed by ruptured blisters. Review of his skin lesion biopsy done previously revealed the diagnosis of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa dominant type. He denied any prior surgeries. He did not smoke, use alcohol or any illicit drug. He lived with his mother who was apparently healthy without any chronic skin disease. His mother was separated from his father and did not have any details about his father’s medical conditions.

On examination, he appeared comfortable, afebrile with pulse 93 beats per minute, blood pressure 111/68 mmHg, respiratory rate 18 per minute and body mass index (BMI) was 16.1 kg per square meter. He had extensive erosions and crust formation with whitish papules involving face, neck, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1). On examination of his extremities, many of his finger and toenails were missing (Figure 1). His oral cavity examination and the systemic examination including chest, cardiac, abdomen and neurological examination were unremarkable.

During his hospital stay, an esophagogram was done which showed tight stenosis at the level of cervical esophagus (Figure 2). An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed which showed a tight stenosis involving the upper esophagus (Figure 3). Stenosed region of the upper esophagus could not be traversed even with the use of an extra slim 5.5 mm diameter endoscope. Patient eventually underwent a percutaneous gastrostomy tube placement.

A German dermatologist Heinrich Koebner coined the term epidermolysis bullosa in 1886[1]. Epidermolysis bullosa comprises a group of hereditary disorders characterized by recurrent mucocutaneous blisters that result from minor trauma. Due to several genotypic and phenotypic variants of epidermolysis bullosa, classifying this group of disorder was challenging. In 1962, Epidermolysis bullosa was first classified by Pearson based on the detailed structures of dermo-epidermal junction as seen on the electron microscope[2]. Since then the group of experts have had four international consensus meetings on diagnosis and classification of epidermolysis bullosa to include all the subclasses under one classification system.

The last international consensus meeting results were released in 2014 and the expert group continues to recognize epidermolysis bullosa into four major types based on the level of cleavage in the skin layers[1]. Skin is composed of an outer epidermis, inner dermis and an intermediate layer called basement membrane zone, which lies between the epidermis and dermis. Basement membrane zone has been further divided into four layers - hemidesmosome, lamina lucida, lamina densa and sub-lamina densa[3]. Four major types (Figure 4) of epidermolysis bullosa with their level of cleavage are – EBS (intra-epidermal cleavage), JEB (intra-lamina lucida cleavage), DEB (intra sub-lamina densa cleavage) and kindler syndrome (multiple levels of cleavage)[1].

Epidermolysis bullosa has a variable worldwide prevalence. The variability is likely due to genetic differences between different populations but the differences in recognizing and reporting of the disease are also contributory. In countries where epidermolysis bullosa registries have been established, epidemiological data is slowly emerging but is still underestimated. Prevalence of 10 per million in Australia[4], 49 per million in Scotland[5], 32 per million in Ireland[6] and 10.1 per million in Italy[7] has been reported. In United States, National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry (NEBR) was founded in 1986 and since then it has emerged as the largest registry of epidermolysis bullosa in the world. According to 1990 estimates of NEBR, the prevalence of epidermolysis bullosa was 8 per million in United States[8].

Epidermolysis bullosa is inherited as an autosomal dominant or an autosomal recessive disease. Mutations in genes encoding for structural proteins of epidermis, dermis and basement membrane zone are responsible for the fragility of the skin. Phenotypic heterogeneity of epidermolysis bullosa depends on the structural protein involved. Various proteins implicated in different subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa are shown in Figure 4[9].

Cutaneous manifestations: Skin blisters are the most prominent manifestations of epidermolysis bullosa. Blisters may involve oral mucosa as well. Besides skin blisters, other skin lesions described in literature are erosions, milia (small white papules), deformity or absence of finger and toenails, scarring and extensive granulation tissue. Skin lesions vary in severity and extent among different subtypes.

EBS is the predominant type prevalent in western countries and in general has milder skin lesions as compared to JEB or DEB. The herlitz subtype of JEB is less prevalent than the non-herlitz JEB, but both can have characteristic enamel hypoplasia. Skin scarring is a predominant feature of herlitz subtype JEB. In addition, involvement of the mucosal surfaces of esophagus, upper airway and cornea with subsequent scarring can also be seen with herlitz subtype JEB. The non-herlitz JEB has fewer tendencies to develop extra-cutaneous manifestations. Dominant form of DEB develops skin blisters at birth. Recurrent involvement of esophagus with subsequent scarring and stenosis can be seen among these patients. Recessive form of DEB is the most severe form of epidermolysis bullosa and leads to disfiguring skin scars, hand and foot deformities, growth retardation and failure to thrive. Kindler syndrome is characterized by photosensitivity and skin pigmentation besides skin blistering[8].

Epidermolysis bullosa, in addition to skin involvement, may involve extra-cutaneous sites leading to significant morbidity and mortality. It can involve eye, oral cavity, nose, gastrointestinal tract, genitourinary tract, respiratory tract and heart. Involvement of eye may manifest as conjunctival edema, keratitis, corneal erosions, corneal ulcerations and scarring. Genitourinary involvement may manifest as scarring of glans penis or vaginal vestibule, urethral strictures leading to hydroureter and hydronephrosis. Repeated blisters involving nose, oral cavity and ear may lead to scarring and occlusion of external nares, oropharynx and external auditory canal. Blisters may involve larynx and upper respiratory tract epithelium leading to scarring and respiratory compromise[10]. Musculoskeletal involvement in recessive DEB is characterized by extensive blistering and scarring that eventually leads to fusion of fingers and toes (mitten deformity). Other features of musculoskeletal involvement are contractures involving multiple joints, muscular dystrophy and osteoporosis.

Anemia is commonly seen in patients with JEB and recessive DEB. Cardiomyopathy secondary to micronutrient deficiencies, anemia and transfusion related iron overload has been uncommonly seen in recessive DEB. Skin cancers like squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and melanoma are also known to occur in patients with epidermolysis bullosa[11]. Squamous cell carcinoma is the leading cause of mortality in several subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa. It most commonly affects recessive form of epidermolysis bullosa and the cumulative risk increases with age[12].

The gastrointestinal tract is commonly involved in different subtypes of epidermolysis bullosa. Repeated blistering of the esophageal mucosal surface most commonly leads to scarring and stenosis of the upper esophagus. The resulting strictures can vary in length and may involve multiple sites. Recessive type of DEB is the subtype most commonly associated with esophageal strictures, however other types including dominant DEB, JEB and EBS may also show similar findings[13]. Analysis of 3280 epidermolysis bullosa patients enrolled in National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry showed the highest cumulative risk of esophageal strictures in the recessive subtype of DEB. Cumulative risk of about 95% and 35% were seen respectively in patients with recessive DEB and herlitz JEB[14].

Patients usually present with symptoms of dysphagia, odynophagia and malnutrition. Strictures, though commonly affect the upper esophagus, may involve mid and lower esophagus as well. Lower esophageal strictures can be precipitated by gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) besides blistering of the mucosa. The other common gastrointestinal problems affecting epidermolysis bullosa patients are constipation and fecal impactions, which result from painful perianal blistering or anal canal stenosis. Pyloric atresia that mostly involves JEB patients is another serious gastrointestinal problem that manifests early in life[11].

Currently there is no effective therapy available for curing epidermolysis bullosa. However, over the last decade several potential future therapies including protein replacement and gene therapies have been explored. Model systems using these approaches show promise for significant advances in future. Gene therapy for non-Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa has been performed and shown to be efficacious[15]. In the absence of a definite therapeutic modality to cure or modify epidermolysis bullosa disease course, management is largely symptomatic. Management of skin lesions focuses on avoiding further skin trauma and secondary bacterial infections[8].

Dietary modification with fiber supplementation is an effective initial approach to manage constipation. Osmotic laxatives can also be tried if dietary measures fail. GERD symptoms usually respond to histamine type 2 receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors.

Treatment of an esophageal stricture begins with modification of diet texture to soft, puree and liquids. Supplementation of multivitamins and minerals is an additional important measure. Despite these measures, patients may not be able to keep up with the required caloric intake resulting in malnutrition and growth retardation. Severe strictures eventually may require esophageal dilatation that can be done either with the use of a balloon catheter or a bougie. Both the methods have comparable efficacy, however balloon catheters are preferred due to their relative safety over bougies. Single or multiple sessions of esophageal dilatations may be needed. Usually an antegrade approach is used where a balloon catheter is inserted from the mouth under endoscopic or fluoroscopic guidance. In cases with microstomia due to oropharyngeal scarring, a retrograde approach from the gastrostomy tube may also be tried. With each dilatation small but definite risk of esophageal perforation exists[16]. Rarely, colonic interposition or transposition has also been used. Management of most of these complications of epidermolysis bullosa requires a multi-modality approach with multi-disciplinary coordination.

A 15-year-old boy with blistering skin disease since birth, dysphagia since age nine presented with worsening dysphagia for 3 d.

He had extensive skin erosions and crust formation involving face, neck, trunk, and extremities and many of his finger and toenails were missing.

Four main types of epidermolysis bullosa: epidermolysis bullosa simplex, junctional epidermolysis bullosa, dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa and kindler syndrome.

Skin lesion biopsy showed dominant type dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Esophagogram showed tight stenosis at the level of cervical esophagus and an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a tight stenosis involving the upper esophagus.

Gene mutation affecting collagen VII leads to skin blisters involving uppermost part of dermis.

Management of skin lesions is largely symptomatic but protein and gene replacement therapies are emerging. Worsening dysphagia may require esophageal stricture dilatation or gastrostomy tube placement.

Recessive type of dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) is the subtype most commonly associated with esophageal strictures, however other types including dominant DEB, junctional epidermolysis bullosa and epidermolysis bullosa simplex may also show similar findings.

Epidermolysis bullosa comprises a group of hereditary disorders characterized by recurrent mucocutaneous blisters that result from minor trauma.

This case report highlights the association of skin blisters, missing nails and dysphagia in patients with epidermolysis bullosa.

This is a very nice case report.

| 1. | Fine JD, Bruckner-Tuderman L, Eady RA, Bauer EA, Bauer JW, Has C, Heagerty A, Hintner H, Hovnanian A, Jonkman MF. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa: updated recommendations on diagnosis and classification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:1103-1126. |

| 2. | Pearson RW. Studies on the pathogenesis of epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 1962;39:551-575. |

| 3. | Chan LS. Human skin basement membrane in health and in autoimmune diseases. Front Biosci. 1997;2:d343-d352. |

| 4. | Murrell DF. Epidermolysis bullosa in Australia and New Zealand. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:433-438, xvi. |

| 5. | Horn HM, Priestley GC, Eady RA, Tidman MJ. The prevalence of epidermolysis bullosa in Scotland. Br J Dermatol. 1997;136:560-564. |

| 6. | McKenna KE, Walsh MY, Bingham EA. Epidermolysis bullosa in Northern Ireland. Br J Dermatol. 1992;127:318-321. |

| 7. | Tadini G, Gualandri L, Colombi M, Paradisi M, Angelo C, Zambruno G, Castiglia L, Annicchiarico G, Hasheem MEL, Barlati S. The Italian Registry of hereditary epidermolysis bullosa. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2005;140:359-372. |

| 8. | Fine JD. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2010;5:12. |

| 9. | Bruckner-Tuderman L, Has C. Molecular heterogeneity of blistering disorders: the paradigm of epidermolysis bullosa. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:E2-E5. |

| 10. | Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: part I. Epithelial associated tissues. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:367-384; quiz 385-386. |

| 11. | Fine JD, Mellerio JE. Extracutaneous manifestations and complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: part II. Other organs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:387-402; quiz 403-404. |

| 12. | Mallipeddi R. Epidermolysis bullosa and cancer. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27:616-623. |

| 13. | Travis SP, McGrath JA, Turnbull AJ, Schofield OM, Chan O, O’Connor AF, Mayou B, Eady RA, Thompson RP. Oral and gastrointestinal manifestations of epidermolysis bullosa. Lancet. 1992;340:1505-1506. |

| 14. | Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Gastrointestinal complications of inherited epidermolysis bullosa: cumulative experience of the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:147-158. |

| 15. | Mavilio F, Pellegrini G, Ferrari S, Di Nunzio F, Di Iorio E, Recchia A, Maruggi G, Ferrari G, Provasi E, Bonini C. Correction of junctional epidermolysis bullosa by transplantation of genetically modified epidermal stem cells. Nat Med. 2006;12:1397-1402. |

| 16. | Mortell AE, Azizkhan RG. Epidermolysis bullosa: management of esophageal strictures and enteric access by gastrostomy. Dermatol Clin. 2010;28:311-318, x. |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Al-Biltagi M, de Bortoli N, Dumitrascu DL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN