INTRODUCTION

The term “achalasia” (from the Greek “alfa” and “chalasis”, words for absence of relaxation) was introduced by Lendrum in 1937[1]. Before that and since then, a host of other names have been used, including achalasia cardiae, cardiospasm, and esophageal aperistalsis, reflecting the key physiological abnormalities of the disease. The incidence of achalasia is expected to be 1 in 100000 persons per year with a prevalence of 10 in 100000. This disorder can appear at any age, with a two peaks incidence at 20-40 and 70-80 years, without gender prevalence[2]. Esophageal achalasia has been credited to a loss of myenteric plexus ganglionic cells in the esophagus, but its cause remains uncertain[3,4]. Achalasia is characterized by the absence of esophageal body peristalsis associated with an impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), and usually with an elevated LES pressure[5,6]. Obviously, these features lead to a failure in the passage of bolus through the esophagogastric junction. The predominant symptom in most patients with achalasia is dysphagia, often for both solids and liquids, or “paradoxical” (first for liquids, then for solids) as a distinction from organic dysphagia. Other symptoms often reported are listed as regurgitation, chest pain, heartburn, and weight loss. Patients with achalasia may also present with symptoms such as slow eating or “augmenting pressure” manoeuvres, to allow a bolus passage through gastric cardia; this may hesitate in delaying medical examination, with a progressive dilation of esophageal lumen[7]. Patients who are suspected to be affected by achalasia commonly require endoscopy, barium esophagram and esophageal manometry for diagnosis[8]. Endoscopic evaluation of the esophagus and stomach must rule out a malignancy or a stenosis causing dysphagia. In achalasia patients, it is common to detect a dilation of esophageal lumen, with food deposit and fluid collection; tight LES appears to be tight and passage through the esophago-gastric junction with the endoscope is perceived as a “pop” opening. Nevertheless, a common esophagus appearing at upper endoscopy can be found, because up to 40% of patients with early-stage disease will have an apparent lack of dilated esophagus[9]. On barium esophagram, achalasia is characterized by the presence of a dilated esophagus, absence of peristalsis, and an impaired passage at the esophagogastric junction, associated with symmetric, smooth narrowing of the region (“bird’s beak” sign). Accumulation of barium is seen in the body of the esophagus, especially in patients with huge dilation and curvature of the lower esophagus[10]. Although endoscopic examinations and esophagography currently play an important role in the diagnosis, esophageal motility evaluation by means of manometry is considered the “gold standard” test for achalasia. Classically, at standard esophageal manometry, achalasia is diagnosed when esophageal body peristalsis is totally lacking (absence), often associated to a LES resting pressure > 45 mmHg (hypertensive) and a poorly relaxing LES (residual pressure > 8 mmHg)[11]. Recently, high-resolution manometry (HRM) has been introduced as a new technique for the evaluation of esophageal motility disorders. HRM uses 1 cm spaced pressure sensors spanning thorough the whole esophagus, distal pharynx and proximal stomach, enabling the motility to be displayed as concrete colour images. The new Chicago classification has been proposed to classify esophageal motility disorders on HRM. Achalasia is now organized into 3 types (I, II and III) according to the esophageal motor function[12]. In particular, “classic achalasia” (Type I) appears as a peristaltic esophagus with no distal increase in pressure > 30 mmHg; “achalasia with pan-esophageal compression”, or type II, has to show at least 20% of liquid swallows with a body pressurization > 30 mmHg, and “spastic achalasia” (type III) is described when at least 20% of liquid swallows appears to be spastic contractions, associated or not to a pressurization. In this study, the authors showed that achalasia with pan-esophageal compression was associated with a better symptom response and a lower necessity to undergo several treatments than the other 2 types. A definitive cure for achalasia is currently unavailable. Palliative treatment options provide only transit of food and liquid bolus through the gastroesophageal junction, thereby relieving feeding and symptoms. These treatments include drug therapy, endoscopic botulinum toxin injection (BTI), endoscopic pneumatic dilation (PD), per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), and surgical extramucosal myotomy, with or without an anterior, posterior or total fundoplication. This article will review different endoscopic treatments in achalasia, and summarize the short-term and long-term outcomes.

ENDOSCOPIC BOTULINUM TOXIN INJECTION

Botulinum toxin can impede the release of acetylcholine from cholinergic neurons. Chemical denervation after an injection of botulinum toxin is intended to lower both basal and residual LES pressure, therefore reducing bolus obstruction[13,14]. Usually, an endoscopic needle is used to inject 20 to 25 units of botulinum toxin into quadrants, at the squamocolumnar junction or up to 1 cm proximally, for a total dose of 80 to 100 units. Recommendations are given to inject the toxin equally in a circumferential manner and at the same level, avoiding submucosal injection or injection outside the esophageal wall. Different authors proposed alternative solutions to improve outcomes, such as injecting by means of endoscopic ultrasound or using different types of botulinum toxin, but these remained only experimental practices[15]. Commonly, 70%-80% of patients referred showed relieved or improved symptoms within 30 d after the procedure.

After BTI, patients occasionally referred transitory non-cardiac chest pain and only those who experienced a beneficial effect of the toxin rarely reported reflux. Severe complications related to BTI are reported only as isolated cases (fatal arrhythmia, gastroparesis and mediastinitis), probably due to technical difficulties during procedures[16]. In an initial study, Pasricha et al[17] reported 82% of patients with dysphagia improvement after BTI. Annese et al[18] showed 75% of subjects with dysphagia remission at 2 years follow-up; however some of the patients required at least one repeated BTI. The short-term effectiveness of BTI was also investigated by Neubrand et al[19] using esophageal manometry 1 wk after treatment; LES pressure dropped from 62.1 ± 15.2 mmHg to 43.1 ± 12.5 mmHg (P < 0.01). However, symptomatic remission induced by BTI usually decreases within one year (40.6% at one year or longer)[20]. Also, the appearance of antibodies against botulinum toxin or development of regional fibrosis can dissipate the effects of successive injections[21]. BTI was found to be effective only in the short-term evaluation, with reduced benefit within 2 years after injection and eventually with none after repeated injections[22,23]. Because of these limitations, BTI is best reserved for patients who are too ill to undergo surgery, such as elderly patients or patients whose disease is complicated by overlapping diseases or those declining surgery or PD[24]. Compared to PD and surgery (myotomy), BTI was clearly inferior at mid and long term efficacy[25]. A recent Cochrane Review evaluated 178 patients from 6 randomized, controlled trials after esophageal dilation vs endoscopic botulinum toxin injection. At one year follow up, up to 74% of patients who underwent BTI were found to have failed treatment, compared to 30% of patients who underwent dilation[26]. Also, Campos et al[20], performing a systematic review and a meta-analysis on 7855 achalasia patients, found a better symptomatic relief when treated by PD than BTI. A recent review on 5 best evidence papers trials on BTI vs surgical myotomy reported that surgery should be the first line treatment due to its superior long-term clinical success rate[27]. BTI has been used as rescue treatment after unsuccessful PD or surgical myotomy[28]. There is an increased risk for perforation during PD[29], or increased difficulty of performing esophagomyotomy after BTI[30].

PNEUMATIC DILATION

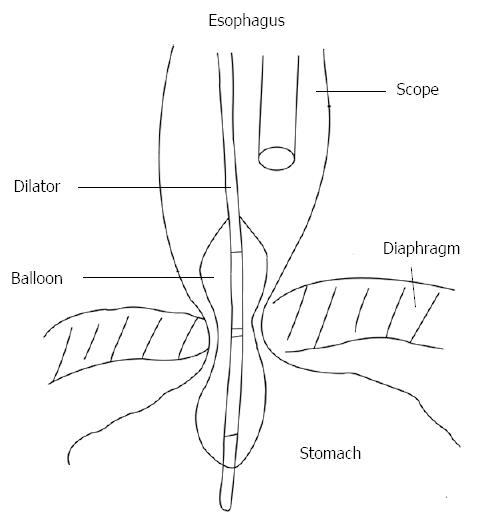

Pneumatic dilation (PD) in patients with achalasia aims to forcibly fracture the muscularis propria, decreasing LES pressure and thereby improving bolus transit through cardia. Forceful dilation of the LES dates back to 1674, when Willis used whalebone as a prototypic bougie to accomplish distraction of the muscular fibres in the esophago-gastric junction[31]. Subsequently, dilation has been performed by various techniques. In fact, up to date, there is no well-standardized, unique technique performing PD in achalasia patients, with different technical modifications. Recently, a ≥ 3 cm polyethylene low-compliance balloon (Rigiflex Achalasia Balloon Dilator, Boston Scientific, Boston, MA, United States) has been most widely used because it is considered the safest and most effective[20], nevertheless other companies produce analogous devices. These polyethylene balloons are more consistent than latex ones, with the advantage that a fixed diameter (usually as 30, 35, 40 mm sizes) can be achieved during inflation. The position of balloon across the LES is typically performed using a guidewire and fluoroscopy. In recent times, PD has been performed during endoscopic direct imaging rather than fluoroscopy guidance in order to avoid radiation exposure and to obtain a better clinical response and limiting complications (Figure 1). However, even if both fluoroscopically and endoscopically guided PD are safe and effective techniques, the authors were not able to demonstrate differences in outcomes[32]. During endoscopy, a metallic guidewire with a soft distal tip is passed through the LES, then the balloon is put along the wire, until its centre is correctly placed through the esophagogastric junction. After fixing the device by a firm grasp to avoid distal migration during the procedure, the balloon is filled slowly with air until a value of 7 to 10 psi on sphygmomanometry is reached. The aim is to sustain dilation until the LES waist appears closed around the balloon; some prefer a prolonged dilation whereas others deflate the balloon immediately afterwards[33]. Then the balloon device and guidewire are removed. Commonly, blood presence around the balloon cannot be considered a useful marker of successful PD. With the use of a Rigiflex Achalasia Balloon Dilator, the mean time required to reach the required pressure for PD was reported to be 73 s (range, 6-240 s), with a mean dilation pressure of 10.9 psi (range, 7-18)[20]. Usually, an esophageal RX transit with hydro-soluble (gastrografin) contrast agent can be carried out after anesthesia recovery, to verify the presence of lumen perforation and perhaps treatment outcome. There is general agreement that a single dilation, when successful, could be more efficient over time. However, patients typically require serial dilations to remain clinically silent. Success rates of PD are reported up to 84.8% within one month after the procedure, as stated in a systematic review carried out by Campos et al[20] However, success rates declined on longitudinal follow-up; in fact, the success rate was reported to be 73.8% at 6 mo, 68.2% at one year, and 58.4% at 3 years or longer. Also, 25% of patients required a second or a repeated PD. Several studies with a long-term follow-up are currently available. Eckardt et al[34] showed with a unique PD a response of 40% at 5-year follow-up, and patients with relieved symptoms at 5 years were more likely to continue in this way, whereas Zerbib et al[35] reported an estimated efficacy of 97% and 93% at 5 and 10 years respectively, but frequently with repeated PD. In a study on 209 patients with a mean follow up of 70 mo, a success rate with balloon dilation was observed in 72% of subjects[36]. However, in these studies PD is not routinely repeated, but only performed on demand for still-symptomatic patients; instead, in the study by Hulselmans et al[36] patients repeated PD with a bigger balloon only if manometry and barium esophagram did not show optimal treatment outcomes. Long-term efficacy of PD was investigated only in a few studies that have followed-up patients over a decade[37]. The authors concluded that PD, when performed by experienced operators, can achieve good to excellent outcomes (defined as a better swallowing ability and a better quality of life); however, only a few patients can be definitively treated with a first, single dilation, needing repeated dilations at long term follow-up[38]. The most common complication of PD is esophageal perforation, being reported to occur, fortunately, in less than 5% of dilations. Moreover, improvements in balloon materials and other factors have decreased the incidence of perforation to 1.6% on average[20,39]. PD-associated perforation seems to not be related to any well confirmed risk factors and there is no evidence that larger balloons are linked to an increased perforation rate[40]. The PD-linked overall complication rate is estimated to be lower than 10%; these include perforation, transient non-cardiac chest pain, esophagogastric lacerations, hematomas, hemorrhage, fever, and formation of diverticula[41]. Esophageal perforation may be treated with a completion myotomy emergently by a laparotomy, or more recently, performed via laparoscopy[42]. Reflux symptoms can be present after PD, reflecting a success in widening the gastroesophageal junction[43]. Several factors are considered responsible for predicting outcomes after PD. Eckardt et al[44] showed that, if after PD a manometrical-determined LES pressure of 10 mmHg or less is achieved, this can be the most important predictor of long-term clinical response and that response rates in patients younger than 40 years are relatively lower. Duranceau et al[45] reported that grade 4 achalasia patients (“sigmoid esophagus” or “end-stage” disease) generally do not show a good response to PD (or to other treatments). Ghoshal and colleagues instead reported that poor outcomes were associated with sex (male gender) and with a missed drop in LES resting-pressure > 50% after dilation, but they were not related to age, or other factors such as elevated dysphagia score, presence of regurgitation, end stage esophagus, or initial LES resting-pressure[46,47]. Recent use of HRM has suggested, based on Chicago classification, that those with type I and type II (classic and compressive achalasia, respectively) respond much better to PD than those with type III (spastic achalasia)[48]. The role of PD in comparison to surgery is still debated. Both techniques produce an optimal initial resolution of dysphagia; nevertheless surgery is considered to be superior at longer follow up[22,49]. A study by Gockel et al[50] showed comparable clinical outcomes with surgical myotomy and PD, but surgery achieved a better LES resting-pressure drop. On the other hand, only a few prospective randomized controlled trials comparing these techniques are available in the literature. There has been a single randomized prospective trial examining outcomes in 81 patients after Heller myotomy plus Dor fundoplication vs pneumatic dilation, with a median follow-up of about 5 years[51]. In this trial, investigators found that patients undergoing myotomy resulted in similar relief of dysphagia, but had fewer relapse of symptoms at longer follow-up than those patients undergoing PD (95% success rate vs 65%, respectively). However, an important limitation of this study was that dilation was performed with a Mosher bag rather than with a Rigiflex balloon dilator, currently considered the most effective dilator. In a prospective randomized study by Boeckxstaens et al[52], PD was compared with surgical therapy (laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus Dor’s fundoplication), using a rigorous design. The study included 201 patients, with a 43 mo mean follow-up; at 12 mo, the two groups showed no significant difference in dysphagia and overall Eckardt score. At 24 mo, the success rate was similar; there was no difference in LES resting-pressure, esophageal transit during RX-barium swallow, or quality of life. However, when a 35-mm balloon was used for dilation in this study, perforation occurred in 4 (31%) of 13 patients. This protocol was abolished during the study. With a balloon 30 mm in diameter, the perforation rate decreased to 4%. In either case, however, PD is associated with a substantial risk of perforation and has not been shown to be clearly superior to surgical therapy in terms of safety. PD can be also considered for a second treatment (“salvage”) in patients that had a prior unsuccessful myotomy, but the efficacy rate is reported to be lower when compared to those patients who underwent only dilation[53].

Figure 1 Pneumatic dilation under direct endoscopic guidance (from ref.

[32]).

PER ORAL ENDOSCOPIC MYOTOMY

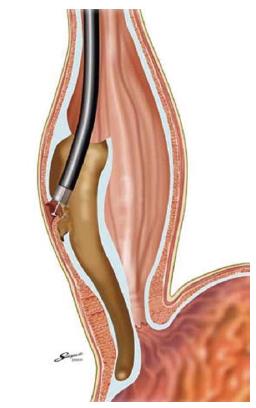

Per oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM), first described by Inoue et al[54,55] developed from a technique to access the mediastinum in Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES)[56]. The technique of POEM can be summarized in the following steps: (1) lift of submucosa by injection, and creation of esophageal mucosa tear; (2) tunnellization in the submucosal space; (3) identification and separation of esophageal circular muscle; (4) myotomy; and (5) repair of the mucosal tear. A fundamental step of POEM is the creation of a submucosal tunnel with subsequent closure of the mucosal tear entry site away from the myotomy (Figure 2). An endoscopic myotomy of inner circular muscle within this tunnel is then performed, accomplishing a minimal dissection of the LES circular muscle. The myotomy of clasp fibers is performed by grasping the inner muscle layer with a hook and dividing them with an electrocautery-based device. This dissection of muscle is continued distally until it is extended 1-2 cm into the cardia. The overall cut length is approximately 12 cm. The mucosal defect is closed with endoscopic clips. Finally, an easy and smooth passage of an endoscope through the gastroesophageal junction is confirmed at the end of the procedure. This procedure is performed during general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation. Inoue et al[55] initially indicated POEM for the treatment of early-stage achalasia, but recently he described POEM performed in 16 sigmoid achalasia patients, extending the indication to all categories of achalasia, including longstanding disease. Contraindications to endoscopic myotomy include severe pulmonary disease, significant coagulation disorder and prior therapy that compromise esophageal mucosal integrity. Inoue et al[57] have treated 43 cases of achalasia, with a maximum follow-up period of 1 year 9 mo. Symptoms of achalasia decreased or disappeared in all patients. The LES pressure decreased significantly after the procedure. No specific complications related to POEM were reported. Although about 10% of patients had gastroesophageal reflux disease after the procedure, symptoms resolved in response to treatment with a proton-pump inhibitor. Actually, there are only series from a few centers[58,59] but literature on POEM is drastically increasing, reflecting the world wide interest in this technique. In follow-up studies, von Renteln et al[60] used POEM to treat 16 patients with achalasia and reported similar, favourable results; Li et al[61] reported a treatment success (Eckardt score ≤ 3) in 96% (95 of 99) of patients treated with a full-thickness myotomy and in 95% (115 of 121) of patients treated with circular muscle myotomy. Recently, 70 patients who underwent POEM at 5 centres in Europe and North America, were enrolled in a prospective, international, multicenter study, aiming to determine the outcomes of this technique[62]. At the first follow-up (3 mo) after the procedure, 97% of subjects displayed complete symptom relief (95%CI: 89%-99%); dysphagia and other mean symptoms scores dropped from 7 to 1 (P < 0.001) and LES resting-pressures fell from 28 to 9 mmHg (P < 0.001). At 6 and 12 mo follow-up visits, symptom relief was found in 89% and 82% of patients, respectively. The authors concluded that POEM, at a 10 mo mean follow-up, can be considered an effective treatment in the management of achalasia. Swanstrom et al[63] described 6-mo physiological and symptomatic outcomes in 18 patients after POEM for achalasia. The authors found that all investigated patients displayed remission of dysphagia (dysphagia score ≤ 1), whereas only 2 patients showed Eckardt scores > 1, related to persistent non cardiac chest pain. During the POEM procedure, 3 intraoperative complications were noted: 2 gastric mucosal tears and 1 esophageal perforation. In all patients, surgeons were able to repair the esophageal and gastric wall endoscopically without any further comorbidity. All patients reported a persisting dysphagia resolution at 11.4 mo mean follow-up. Postoperative LES relaxations and esophageal transit were found to be strongly improved, when investigated by manometry and RX barium esophagogram, respectively. However, the postoperative presence of gastroesophageal reflux was objectivized in 46% of patients. The latter data are in contrast with the low rate (10%) of reflux reported by Inoue[55]. In theory, POEM might not damage anti-reflux barriers such as phrenoesophageal ligamentous attachments and, therefore, may not additionally require an anti-reflux procedure. Gastroesophageal reflux should be prevented to some extent, but objective studies, as previously performed after laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus fundoplication[64,65] are needed. Recently, Verlaan et al[66] studied the physiological outcomes of POEM on the esophagogastric junction, reporting 60% rate of reflux esophagitis at endoscopy. Although POEM is expected to become a state-of-the-art technique for minimally invasive surgery in patients with achalasia, it is associated with the risk of serious complications such as mediastinitis and peritonitis caused by perforation of the esophagus or stomach. At present, therefore, it should be performed with caution and only by operators proficient in both esophagoscopic submucosal dissection and open or laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Recent studies compared POEM with laparoscopic Heller myotomy alone[67], or with laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus a partial fundoplication[68], showing similar rates in dysphagia relief. Wider use of POEM would require the results of large, multicentre clinical trials demonstrating the safety of this procedure. Follow-up studies should also be performed to establish the long-term effectiveness of POEM.

Figure 2 Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy; creation of submucosal tunnel and inner myotomy (from ref.

[55]).

CONCLUSION

As endoscopic treatment for achalasia, PD is superior to BTI. Botulinum toxin injection may be reserved for severly ill patients. It is difficult to make definitive conclusions regarding the comparison between PD and surgery with fundoplication, however Heller mytomy with fundoplication appears to be better especially in young patients. POEM is expected to become a valid substitute for Heller myotomy, but long-term outcomes, the real incidence of “de novo” GERD and safety must be confirmed.

P- Reviewer: Chang JH S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Zhang DN