Published online May 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i5.186

Revised: February 7, 2014

Accepted: April 17, 2014

Published online: May 16, 2014

Processing time: 169 Days and 12.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate association(s) between withdrawal time and polyp detection in various bowel preparation qualities.

METHODS: Retrospective cohort analysis of screening colonoscopies performed between January 2005 and June 2011 for patients with average risk of colorectal cancer. Exclusion criteria included patients with a personal history of adenomatous polyps or colon cancer, prior colonic resection, significant family history of colorectal cancer, screening colonoscopy after other abnormal screening tests such as flexible sigmoidoscopy or barium enema, and screening colonoscopies during in-patient care. All procedures were performed or directly supervised by gastroenterologists. Main measurements were number of colonic segments with polyps and total number of colonic polyps.

RESULTS: Multivariate analysis of 8331 colonoscopies showed longer withdrawal time was associated with more colonic segments with polyps in good (adjusted OR = 1.16; 95%CI: 1.13-1.19), fair (OR = 1.13; 95%CI: 1.10-1.17), and poor (OR = 1.18; 95%CI: 1.11-1.26) bowel preparation qualities. A higher number of total polyps was associated with longer withdrawal time in good (OR = 1.15; 95%CI: 1.13-1.18), fair (OR = 1.13; 95%CI: 1.10-1.16), and poor (OR = 1.20; 95%CI: 1.13-1.29) bowel preparation qualities. Longer withdrawal time was not associated with more colonic segments with polyps or greater number of colonic polyps in bowel preparations with excellent (OR = 1.07, 95%CI: 0.99-1.26; OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 0.99-1.24, respectively) and very poor (OR = 1.02, 95%CI: 0.99-1.12; OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 0.99-1.10, respectively) qualities.

CONCLUSION: Longer withdrawal time is not associated with higher polyp number detected in colonoscopies with excellent or very poor bowel preparation quality.

Core tip: This study revealed the merit of a novel finding that longer withdrawal time was not associated with higher polyp number detected in colonoscopies with excellent or very poor bowel preparation quality. The conclusion of this study may change the way we perform screening colonoscopy with excellent or very poor bowel preparation qualities, especially in those with high risk to develop complications related to prolonged sedation.

- Citation: Widjaja D, Bhandari M, Loveday-Laghi V, Glandt M, Balar B. Withdrawal time in excellent or very poor bowel preparation qualities. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(5): 186-192

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i5/186.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i5.186

Polyp detection rate during colonoscopies is influenced by factors including withdrawal time and quality of bowel preparation[1,2]. Barclay et al[1] reported that colonoscopies with longer withdrawal had higher adenoma detection rates. In a similar retrospective study of over 10000 colonoscopies, Simmons et al[3] found that prolonged withdrawal time was associated with higher polyp detection rates and that overall median polyp detection corresponded to a withdrawal time of > 6.7 min. In the same publication year, the American College of Gastroenterology and American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend that the average withdrawal time should exceed 6 min in normal colonoscopies in which no polypectomies or biopsies were performed[4]. The strategy of prolonged withdrawal time may logically increase polyp detection rate during colonoscopies with inadequate bowel preparation qualities, which was reported between 23% and 30% in the United States[5-9]. However, since the implementation of this recommendation, quality improvement efforts by simply mandating a minimal withdrawal time have largely proven to be unsuccessful in significantly improving polyp detection rate[10,11].

Although the effect of longer withdrawal time on higher adenoma detection rate was not related to bowel preparation quality[1], the benefit of this strategy in different bowel preparation qualities was not reported. In this study, we report association between withdrawal time and polyp detection rate in various bowel preparation qualities during screening colonoscopy in an inner city Bronx, NY, United States hospital with a high rate of inadequate bowel preparation quality.

This study was conducted at the Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center (Bronx, NY, United States) and approved by the hospital’s institutional review board. All procedures were performed or directly supervised by six full-time and two part-time gastroenterologists. We reviewed the medical records of all patients who underwent screening colonoscopies between January 1, 2005 and June 30, 2011. Data was collected through ProVationMD, an onsite computer generated medical record system used by endoscopists to create patient reports immediately after procedures. The electronic records of all these patients were reviewed for age, sex, race, date, time of colonoscopy, indication of colonoscopy, family history of colon cancer, timing of colonoscopy, bowel preparation quality, duration of colonoscope withdrawal, and polyp findings. We also collected the names of endoscopists of each case along with their average adenoma detection rates in the last 3 mo.

As per institutional practice at the time, all patients who were evaluated for screening colonoscopy were given verbal and written instructions about diet and laxative use on the day before the procedure. All these patients were instructed to consume a clear liquid diet the day before the procedure, followed by 1 gallon of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution starting at 6 PM the evening before the procedure. In addition, 20-25 mg of bisacodyl was taken at 9 PM. Several endoscopists started giving split doses of PEG in mid-2009 for patients who underwent screening colonoscopy in the afternoon. Patients undergoing procedures before noon were not expected to take laxatives on the day of the procedure. All colonoscopies which were performed before noon were categorized as morning procedures.

Based on the ProVationMD reporting system, the bowel preparation quality was rated as unsatisfactory, poor, fair, good, or excellent. Criteria for each bowel preparation quality are shown in Table 1. All patients who were included in the study had an average risk of colorectal cancer. Screening colonoscopies were performed in an outpatient setting. Patients were excluded if the indication for colonoscopy was associated with an increased risk for colorectal cancer, which included constipation, anemia, weight loss, hematemesis, hematochezia, and positive fecal occult blood test. Other exclusion criteria included patients with a personal history of adenomatous polyps or colon cancer, prior colonic resection, significant family history of colorectal cancer, screening colonoscopy after other abnormal screening tests such as flexible sigmoidoscopy or barium enema, and screening colonoscopies during in-patient care.

| Bowel preparation quality | Criteria |

| Excellent | Mucosal detail clearly visible without washing (suctioning of liquid allowed |

| Good | Minimal turbid fluid in colonic segments and entire mucosa well seen after cleaning |

| Fair | There is minor residual material in the colonic segments. Necessary to suction liquid to adequately view the colonic segments |

| Poor | Necessary to wash and suction to obtain a reasonable view. Portion of mucosa in colonic segments seen after cleaning but up to 15% of the mucosa not seen because of retained material |

| Unsatisfactory | Solid stool not cleared with washing and suctioning. More than 15% of the mucosa not seen |

We evaluated polyp detection outcome based on the distribution and total number of colonic polyps. Distribution of the colonic polyp was defined as the number of colonic segments found to have polyps. We divided the examined intestinal portion examined during colonoscopy into eight segments: (1) rectum; (2) sigmoid colon; (3) descending colon; (4) splenic flexure; (5) transverse colon; (6) hepatic flexure; (7) ascending colon; and (8) cecum. If a polyp or several polyps were found in a colonic segment, the colonic segment would be marked as containing polyps. Therefore, the maximum total number of colonic segments with polyps would be eight. We did not use adenoma detection rate as one of the measured outcomes, as we considered adenoma a pathologic diagnosis, not an endoscopic finding.

The data were collected and analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for MAC version 20. Colonoscopies without bowel preparation quality data were not included in further analysis. Bowel preparation quality was graded by the endoscopists as (1) excellent; (2) good; (3) fair; (4) poor; and (5) unsatisfactory or very poor. The five groups of bowel preparation quality were coded and classified as ordinal data. These groups were used as independent variables in the analysis. The mean duration of colonoscope withdrawal between each group of bowel preparation quality were compared by one-way ANOVA. We evaluated the differences in the number of intestinal segments with polyps and total number of colonic polyps between the five bowel preparation quality groups by Kruskal Wallis test.

Further analysis was performed to measure the correlation between polyp detection outcomes (number of colonic segments with polyps and total number of polyps) and withdrawal time using ordinal regression analysis. In this analysis, the number of intestinal segments with polyps or total number of colonic polyps was used as the dependent variable. Other variables, including withdrawal time and bowel preparation quality were included in this analysis as independent variables. Bowel preparation quality was an independent variable during subgroup analysis. Categorical data, such as race, sex, and the presence of a trainee during colonoscopy, were used as factors of independent variables. Continuous and ordinal data (i.e., age, duration of colonoscope withdrawal, timing of colonoscopy, bowel preparation quality, adenoma detection rate of endoscopists, and duration of colonoscopy practice of endoscopists) were included as covariates of the independent variable. Odd ratios and 95%CI were calculated using exponents of estimates obtained from ordinal regression analysis. Statistical significance was defined as P-values ≤ 0.05.

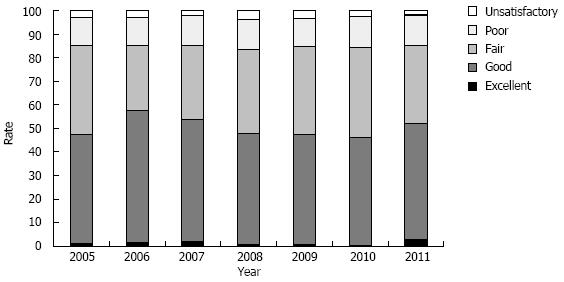

During the study period, there were 8581 screening colonoscopies which fulfilled inclusion and exclusion criteria. There were 250 colonoscopies without documented information of bowel preparation quality, therefore a total of 8331 colonoscopies were used for further analysis. Of these 8331 colonoscopies, bowel preparation quality was distributed as follows: 1% was excellent, 49% were good, 35% were fair, 13% were poor, and 3% were unsatisfactory. The frequencies of bowel preparation quality for each year are shown in Figure 1. The mean age was 58.9 years (range 45-85 years), 58% were women, 24% were non-Hispanic Blacks, and 62% were Hispanic. Characteristics of the subjects based on the quality of bowel preparation are shown in Table 2.

| Characteristics | Quality of bowel preparation | ||||

| Excellent (n = 108) | Good (n = 4051) | Fair (n = 2889) | Poor (n = 1045) | Unsatisfactory (n = 238) | |

| Mean age ± SD, yr | 58 ± 7.6 | 59 ± 7.6 | 59 ± 7.9 | 60 ± 7.7 | 59 ± 8.3 |

| Women | 65 (60) | 2481 (61) | 1596 (55) | 537 (51) | 117 (49) |

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 1 (1) | 32 (1) | 16 (1) | 4 (0) | 0 (0) |

| White | 1 (1) | 47 (1) | 34 (1) | 15 (1) | 5 (2) |

| Black | 25 (23) | 875 (22) | 697 (24) | 280 (27) | 82 (35) |

| Hispanic | 81 (75) | 3097 (77) | 2142 (74) | 746 (71) | 151 (63) |

| Morning procedure | 45 (42) | 1877 (46) | 1212 (42) | 428 (41) | 78 (33) |

Distribution of mean duration of colonoscope withdrawal based on bowel preparation quality is shown in Table 3. The longest mean duration of colonoscope withdrawal was seen among subjects with fair quality. Subjects with excellent bowel preparation quality had the shortest mean duration of colonoscope withdrawal.

| Quality of bowel preparation | P-value | |||||

| Excellent (n = 108) | Good (n = 4051) | Fair (n = 2889) | Poor (n = 1045) | Unsatisfactory (n = 238) | ||

| Mean duration of colonoscope withdrawal ± SD, min | 10 ± 5.5 | 12 ± 5.3 | 13 ± 5.9 | 12 ± 5.2 | 11 ± 9.4 | < 0.001 |

| No. of colonic segments with polyps | < 0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 85 (77) | 2707 (67) | 1799 (62) | 703 (67) | 181 (76) | |

| 1 | 17 (16) | 769 (19) | 581 (20) | 223 (21) | 38 (16) | |

| 2 | 3 (3) | 375 (9) | 305 (11) | 74 (7) | 13 (6) | |

| 3 | 1 (1) | 136 (3) | 145 (5) | 31 (3) | 6 (3) | |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 43 (1) | 38 (1) | 11 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| 5 | 0 (0) | 16 (0) | 18 (1) | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 6 | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 3 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 7 | 0 (0) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 8 | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Total No. of colonic polyps | < 0.001 | |||||

| 0 | 85 (77) | 2707 (67) | 1799 (62) | 703 (67) | 181 (76) | |

| 1 | 13 (12) | 581 (14) | 446 (15) | 42 (4) | 30 (13) | |

| 2 | 2 (2) | 231 (6) | 164 (6) | 60 (6) | 8 (3) | |

| 3 | 4 (4) | 256 (6) | 195 (7) | 37 (4) | 10 (4) | |

| 4 | 2 (2) | 152 (4) | 155 (5) | 22 (2) | 5 (2) | |

| 5 | 1 (1) | 73 (2) | 90 (3) | 6 (1) | 4 (2) | |

| > 5 | 1 (1) | 51 (1) | 30 (1) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | |

The distribution of the number of colonic segments with polyps and total number of colonic polyps based on bowel preparation quality is shown in Table 3. The overall rate of subjects with no colonic polyps was 66% (5475/8331). The rate of patients with polyps in multiple colonic segments were 7% in the excellent group, 14% in good group, 18% in fair group, 12% in poor group, and 8% in unsatisfactory group.

Odd ratios for each variable in predicting a higher number of colonic segments with polyps and total number of polyps are shown in Table 4. Older age, male sex, longer duration of withdrawal time, bowel preparation quality and higher adenoma detection rate of endoscopist predicted a higher number of colonic segments with polyps and a higher number of polyps found during colonoscopy. Non-Hispanic Black was a predictor for a higher number of polyps found during colonoscopy. However, the duration of colonoscopy practice of the endoscopist had an inverse relationship with the number of colonic segments with polyps and number of polyps found during colonoscopy. The mean ± SD adenoma detection rate of the endoscopist was 26% ± 8.3%. Of the colonoscopy procedures performed, 76.2% (6348/8331) of them performed by endoscopists with high adenoma detection rate, which was defined as a rate greater than 20%. In subgroup analysis, longer withdrawal time was associated with better polyp detection outcomes in patients with good, fair, or poor bowel preparation quality (Table 5). However, among those with excellent or very poor bowel preparation quality, longer duration of withdrawal time was not related to higher number of colonic segments with polyps and higher total number of colonic polyps.

| No. colonic segment with polyps | Total No. colonic polyps | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Older age | 1.01 (1.00-1.03) | 0.011 | 1.01 (1.00-1.02) | 0.026 |

| Gender of male1 | 1.31 (1.11-1.55) | 0.002 | 1.18 (1.00-1.39) | 0.047 |

| Race | ||||

| Asian2 | 0.89 (0.34-2.25) | NS | 1.06 (0.41-2.73) | NS |

| White2 | 0.69 (0.33-1.45) | NS | 0.70 (0.33-1.45) | NS |

| Black2 | 1.17 (0.97-1.41) | NS | 1.22 (1.01-1.47) | 0.041 |

| Later time of colonoscopy | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | NS | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.043 |

| Better bowel preparation quality | 1.10 (1.00-1.21) | 0.04 | 1.11 (1.01-1.22) | 0.030 |

| Longer duration of colonoscope withdrawal | 1.14 (1.12-1.16) | < 0.0001 | 1.14 (1.12-1.16) | < 0.0001 |

| Adenoma detection rate of endoscopist | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | < 0.0001 | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) | < 0.0001 |

| Duration of colonoscopy practice of endoscopist | 0.98 (0.97-0.98) | < 0.0001 | 0.98(0.97-0.99) | < 0.0001 |

| Involvement of trainee during colonoscopy | 0.93 (0.72-1.19) | NS | 0.93(0.73-1.19) | NS |

| No. of colonic segments with polyps | Total No. colonic polyps | |||

| OR (95%CI)1 | P-value | OR (95%CI)1 | P-value | |

| Excellent | 1.07 (0.99-1.26) | NS | 1.11 (0.99-1.24) | NS |

| Good | 1.16 (1.13-1.19) | < 0.0001 | 1.15 (1.13-1.18) | < 0.0001 |

| Fair | 1.13 (1.10-1.17) | < 0.0001 | 1.13 (1.10-1.16) | < 0.0001 |

| Poor | 1.18 (1.11-1.26) | < 0.0001 | 1.20 (1.13-1.29) | < 0.0001 |

| Unsatisfactory/very poor | 1.02 (0.99-1.12) | NS | 1.05 (0.99-1.10) | NS |

Results of this study showed that half of screening colonoscopies in our minority-predominant community were performed with fair, poor, or unsatisfactory bowel preparation quality. The distribution of quality remained unchanged over the years, even though some providers started prescribing split-dose laxatives since mid-2009 for many patients undergoing afternoon screening colonoscopies. Therefore, modification of other factors, including longer withdrawal time, may improve polyp detection rate in this population.

Our study showed that the rate of colonoscopies with single colonic polyps and polyps in multiple colonic segments were highest among those with fair bowel preparation quality. In addition, this group of patients had the longest duration of colonoscope withdrawal. This likely includes patients who at presentation had poor or unsatisfactory bowel preparation quality but were cleaned in order to visualize the colon. This cleaning of intraluminal contents by diluting and suctioning has been recommended by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the American College of Gastroenterology[4,12]. The rating of bowel preparation quality is to be given only after colon cleansing has taken place[12,13]. As a result of this cleansing process, the withdrawal time was prolonged.

Multivariate analysis of our data showed that older age, male sex, longer duration of colonoscope withdrawal, bowel preparation quality, and higher endoscopist adenoma detection rate were independent predictors of higher number of colonic segments with polyps and a higher number of total polyps. Older age, male sex, and adenoma detection rate of the endoscopist were previously reported to be associated with higher polyp detection[14-17], but these factors are not modifiable during a colonoscopy procedure. On the other hand, longer duration of colonoscope withdrawal is an operator-dependent factor, which may be used as a compensatory measure when encountering inadequate bowel preparation quality. In addition, many studies have confirmed the association between this modifiable factor and adenoma detection[1,17-19].

Analysis of each bowel preparation quality group showed that longer withdrawal time was not associated with higher number of colonic segments with polyps or higher total number of colonic segments in those with excellent or unsatisfactory bowel preparation quality. These data may explain the findings of studies reporting no relationship between longer withdrawal time and polyp or adenoma detection rate. Sawhney et al[10] reported that the establishment of a mandatory withdrawal time of ≥ 7 min produced a significant increase in the compliance rate for withdrawal time from 65% to 100%. However, in spite of this, there was no concomitant increase in polyp detection ratio noted for all polyps (slope 0.0006; P = 0.45) or for 1-5 mm (slope 0.001; P = 0.26), 6-9 mm (slope 0.002; P = 0.43), or ≥ 10 mm polyps (slope 0.006; P = 0.13)[10]. A study by Moritz et al[11] also reported that withdrawal time was not associated with detection of polyps > 5 mm in size in a prospective cohort study. In addition, recording of withdrawal time or implementing a withdrawal time policy of > 7 min was not associated with a significant increase in colonic polyp detection[20]. However, all the aforementioned studies did not analyze the effect of withdrawal time based on bowel preparation qualities. It is worth pointing out that with an excellent bowel preparation quality, the completeness of evaluation might have been at a maximum that could not be improved with prolonged withdrawal time. On the other hand, prolonged withdrawal time for cleansing and evaluating the colonic mucosa of those with unsatisfactory or very poor bowel preparation is unlikely to remove solid or semi-solid stool. Therefore, aborting the procedure may be a reasonable option.

Our data showed that a longer duration of colonoscopy practice of endoscopist was inversely associated with a higher polyp detection rate. Harris et al[21] reported that colonoscopies in centers where over 50% of the endoscopists were of senior rank had a higher adenoma detection rate than centers with fewer senior endoscopists. However, the senior endoscopists may have had more patients with a high risk of developing colonic polyps. In addition, the study included diagnostic procedures and colonoscopies for patients with increased risk of colonic cancer. Our finding indicates that the colonoscopy technique (i.e., longer duration of colonoscope withdrawal) and better bowel preparation quality are important factors for senior endoscopists to achieve a higher polyp detection rate during screening colonoscopy in individuals with an average risk.

There are several limitations of this study, including its retrospective nature. In this study, we used overall bowel cleanliness, rather than segmental cleanliness of the bowel. The bowel preparation quality was not assessed for the right colon (cecum, ascending), mid-colon (transverse, descending), and recto-sigmoid, individually. Nonetheless, recent retrospective studies[22-25] of bowel preparation quality included the total bowel preparation scale score for the assessment. Of note, this study defined polyp detection as the number of colonic segments with polyps and number of polyps rather than adenoma detection rate of each colonoscopy. We believe that this outcome measurement reflects the overall colon condition and its endoscopic, not pathologic, lesions. Moreover, a recent study showed that the difference between benign, pre-malignant, and malignant colorectal polyps could not be accurately predicted visually alone[26]. Therefore, all polyps visualized during colonoscopy need to be excised for ex vivo histology regardless of size, location, or predicted pathology.

In summary, based on these data, the longest duration of colonoscope withdrawal time and highest colonic detection rate occurred in colonoscopies with fair quality. Similar to previous studies[1,10,27,28], we found that colonic segments with polyps and total number of colonic polyps are affected by colonoscopic withdrawal time. Further analysis showed that longer withdrawal time was not associated with higher polyp detection among those with an extreme spectrum of bowel preparation quality (i.e., excellent and unsatisfactory/very poor). This study finds that prolonged withdrawal time in those with good, fair, and poor bowel preparation quality is likely beneficial to improving polyp detection during screening colonoscopy.

Many factors influence the finding of colonic polyps during colonoscopy, including clear visualization of the colonic mucosa and completeness of the examination. The presence of a significant amount of stool requiring washing and suctioning prolongs the duration of the colonoscope withdrawal. In contrast, the withdrawal time could be faster in patients with high-quality bowel preparation. The benefit of prolonged duration of colonoscope withdrawal in various degrees of bowel cleanness has not been evaluated.

One study with a large number of samples found that prolonged colonoscope withdrawal time was associated with higher polyp detection rates and that the overall median polyp detection corresponded to a withdrawal time of > 6.7 min. Based on this study, United States gastroenterology societies recommend that the average colonoscope withdrawal time should exceed 6 min, not including time spent for removal of the polyps. However, since the implementation of this recommendation, quality improvement efforts, such as by simply mandating a minimal withdrawal time, have largely proven to be unsuccessful in significantly improving the polyp detection rate.

In this article, the authors showed that half of the screening colonoscopies in minority-predominant community were performed with inadequate bowel preparation quality. Moreover, the rate remained unchanged over the years, even though some providers started new methods of preparation. The authors then showed that prolonged colonoscope withdrawal by endoscopists practicing in this community was beneficial for the majority of cases, except for those with very poor and excellent bowel preparation qualities.

The findings of this study suggest aborting screening colonoscopy procedure in those with very poor bowel preparation quality because a prolonged duration of the colonoscope procedure is unlikely beneficial. On the other hand, prolonging colonoscope withdrawal time by more than the recommended duration in patients with an excellent quality of bowel preparation increases sedation time without benefits in polyp detection.

A colonoscopy is an endoscopic procedure to detect and remove polyps in the large bowel (colon). Polyps in the colon have potential to become cancer. Detail evaluation of the colon is performed while withdrawing the colonoscope after reaching the beginning segment of the colon. Bowel preparation quality is considered unsatisfactory or very poor if the colon contains solid stool that does not clear with washing and suctioning. In this situation, more than 15% of the large bowel wall is not seen. If the detail of the colonic wall is clearly visible without washing, then the bowel preparation quality is considered to be excellent.

It provides new information, particularly for young gastroenterologists and other doctors regarding polyp screening policies. It is a very interesting article and is well documented.

| 1. | Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2533-2541. |

| 2. | Liu X, Luo H, Zhang L, Leung FW, Liu Z, Wang X, Huang R, Hui N, Wu K, Fan D. Telephone-based re-education on the day before colonoscopy improves the quality of bowel preparation and the polyp detection rate: a prospective, colonoscopist-blinded, randomised, controlled study. Gut. 2014;63:125-130. |

| 3. | Simmons DT, Harewood GC, Baron TH, Petersen BT, Wang KK, Boyd-Enders F, Ott BJ. Impact of endoscopist withdrawal speed on polyp yield: implications for optimal colonoscopy withdrawal time. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:965-971. |

| 4. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28. |

| 5. | Harewood GC, Sharma VK, de Garmo P. Impact of colonoscopy preparation quality on detection of suspected colonic neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:76-79. |

| 6. | Cohen SM, Wexner SD, Binderow SR, Nogueras JJ, Daniel N, Ehrenpreis ED, Jensen J, Bonner GF, Ruderman WB. Prospective, randomized, endoscopic-blinded trial comparing precolonoscopy bowel cleansing methods. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:689-696. |

| 7. | Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797-1802. |

| 8. | Kolts BE, Lyles WE, Achem SR, Burton L, Geller AJ, MacMath T. A comparison of the effectiveness and patient tolerance of oral sodium phosphate, castor oil, and standard electrolyte lavage for colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:1218-1223. |

| 9. | Seinelä L, Pehkonen E, Laasanen T, Ahvenainen J. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy in very old patients: a randomized prospective trial comparing oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:216-220. |

| 10. | Sawhney MS, Cury MS, Neeman N, Ngo LH, Lewis JM, Chuttani R, Pleskow DK, Aronson MD. Effect of institution-wide policy of colonoscopy withdrawal time > or = 7 minutes on polyp detection. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1892-1898. |

| 11. | Moritz V, Bretthauer M, Ruud HK, Glomsaker T, de Lange T, Sandvei P, Huppertz-Hauss G, Kjellevold Ø, Hoff G. Withdrawal time as a quality indicator for colonoscopy - a nationwide analysis. Endoscopy. 2012;44:476-481. |

| 12. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873-885. |

| 13. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. |

| 14. | Rex DK, Lehman GA, Ulbright TM, Smith JJ, Pound DC, Hawes RH, Helper DJ, Wiersema MJ, Langefeld CD, Li W. Colonic neoplasia in asymptomatic persons with negative fecal occult blood tests: influence of age, gender, and family history. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:825-831. |

| 15. | Regula J, Rupinski M, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Pachlewski J, Orlowska J, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Colonoscopy in colorectal-cancer screening for detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1863-1872. |

| 16. | Imperiale TF, Wagner DR, Lin CY, Larkin GN, Rogge JD, Ransohoff DF. Risk of advanced proximal neoplasms in asymptomatic adults according to the distal colorectal findings. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:169-174. |

| 17. | Chen SC, Rex DK. Endoscopist can be more powerful than age and male gender in predicting adenoma detection at colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:856-861. |

| 18. | Kaminski MF, Regula J, Kraszewska E, Polkowski M, Wojciechowska U, Didkowska J, Zwierko M, Rupinski M, Nowacki MP, Butruk E. Quality indicators for colonoscopy and the risk of interval cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1795-1803. |

| 19. | Sanchez W, Harewood GC, Petersen BT. Evaluation of polyp detection in relation to procedure time of screening or surveillance colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1941-1945. |

| 20. | Taber A, Romagnuolo J. Effect of simply recording colonoscopy withdrawal time on polyp and adenoma detection rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:782-786. |

| 21. | Harris JK, Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Burnand B, Gonvers JJ, Vader JP. Factors associated with the technical performance of colonoscopy: An EPAGE Study. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:678-689. |

| 22. | Seo EH, Kim TO, Park MJ, Heo NY, Park J, Yang SY. Low-volume morning-only polyethylene glycol with specially designed test meals versus standard-volume split-dose polyethylene glycol with standard diet for colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized trial. Digestion. 2013;88:110-118. |

| 23. | Bae SE, Kim KJ, Eum JB, Yang DH, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. A Comparison of 2 L of Polyethylene Glycol and 45 mL of Sodium Phosphate versus 4 L of Polyethylene Glycol for Bowel Cleansing: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Gut Liver. 2013;7:423-429. |

| 24. | Samarasena JB, Muthusamy VR, Jamal MM. Split-dosed MiraLAX/Gatorade is an effective, safe, and tolerable option for bowel preparation in low-risk patients: a randomized controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1036-1042. |

| 25. | Ibáñez M, Parra-Blanco A, Zaballa P, Jiménez A, Fernández-Velázquez R, Fernández-Sordo JO, González-Bernardo O, Rodrigo L. Usefulness of an intensive bowel cleansing strategy for repeat colonoscopy after preparation failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1578-1584. |

| 26. | Sharma P, Frye J, Frizelle F. Accuracy of visual prediction of pathology of colorectal polyps: how accurate are we? ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:365-370. |

| 27. | Lim G, Viney SK, Chapman BA, Frizelle FA, Gearry RB. A prospective study of endoscopist-blinded colonoscopy withdrawal times and polyp detection rates in a tertiary hospital. N Z Med J. 2012;125:52-59. |

| 28. | Overholt BF, Brooks-Belli L, Grace M, Rankin K, Harrell R, Turyk M, Rosenberg FB, Barish RW, Gilinsky NH. Withdrawal times and associated factors in colonoscopy: a quality assurance multicenter assessment. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:e80-e86. |

P- Reviewers: Damin DC, Goral V, Han HS, Yoshiji H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN