INTRODUCTION

Placement of an esophageal self-expandable stent is a safe and effective procedure to palliate inoperable esophageal carcinoma. Recently, it also has been indicated for the management of benign strictures recalcitrant to endoscopic dilation[1-4].

Migration is one of the most common complications after stent placement, ranging from 4%-36%[5-11]. Although the majority of migrations are asymptomatic, symptoms like recurrent dysphagia and chest pain may arise. A foreign body sensation may be present in cases of proximal dislodgment. Fully covered stents, plastic stents, concurrent chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy and stents placed across the gastroesophageal junction are factors that increase the risk of migration[4,5,12,13].

Management of migrated stents is a controversial issue[14] and it is extremely important that the endoscopist is able to recognize and manage this situation. In this review, we will discuss how to manage stent migration, as well as the endoscopic techniques that can be used for retrieving migrated stents and the new techniques for preventing migration.

CONSERVATIVE APPROACH TO DISTALLY MIGRATED ESOPHAGEAL STENTS

Some authors recommend conservative management of migrated esophageal stents. De Palma et al[15] described 13 cases of esophageal stents migrated to the stomach. Three patients eliminated the stent through the rectum, one underwent surgery for stent impaction in the colon, and in nine patients, the stents remained in the stomach without clinical complications (range, 1.8-6.5 mo). Di Fiore et al[16] described two cases of stent impaction in the duodenum that could not be resolved by endoscopy. The stents were left in place and the patients died of metastatic disease 2 and 10 mo later, respectively. Williams et al[17] related a case of esophageal stent migration to the colon, with the patient presenting with constipation which was resolved conservatively. Indeed, migration of an esophageal stent to the stomach should not be considered an emergency but small bowel obstruction and perforation can occur[18-22], so migrated stents should be removed whenever possible.

ENDOSCOPIC REMOVAL

Endoscopic removal will depend on the kind of stent and the site of migration. When the metallic stent is distally migrated but still in the esophagus, those with a proximal lasso can be pulled back by grasping the lasso with rat-tooth forceps, which allows constriction of the upper flange, permitting repositioning or removal. Endoscopic traction of plastic or metallic stents that do not have a proximal lasso might be trickier. A double-channel endoscope can be helpful for grasping both sides of the upper flange and pulling the stent. In this situation, previous endoscopic dilation is advisable if a proximal stricture is present.

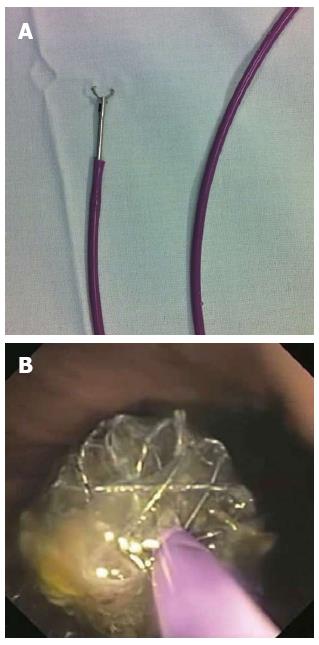

A more challenging situation is when a stent migrates to the stomach. Metallic stents with a proximal lasso can be removed by grabbing and pulling the lasso. However, in some cases, constriction is not enough to remove the stent without esophageal injury, especially if a stenotic tumor is present. Some techniques have been developed to deal with this situation: (1) Endoloops: one or more endoloops may be placed to reduce the size of the stent and facilitate its removal[23,24]; (2) Polypectomy snare: one of the flanges of the stent can be grasped with a polypectomy snare, reducing the proximal diameter and making stent removal possible[25]. Some variations of this technique have been described when collapsing the stent proves to be difficult. One example is the use of a snare and rat-tooth forceps passed through a double-channel endoscope. The forceps is passed through the snare, which is advanced along the forceps and closed, grasping the stent[26]. Another technique variation is the replacement of the plastic sheath of the snare by a metallic sheath from a basket designed for bile duct stone lithotripsy[27]. The stiffness of the metallic sheath facilitates the collapsing of the stent by the snare; (3) “Push and grasper” technique: a biliary stent pusher (10 Fr for double-channel and 7 Fr for standard endoscope) is inserted into the operational channel and a grasp forceps is passed inside the pusher (pediatric, 7 Fr pusher) (Figure 1). The lasso is grasped and pulled back into the pusher while the pusher is advanced against the stent. This maneuver allows constraining of the proximal flange of the stent, facilitating its removal[28]; (4) A foreign body hood protector in combination with a rat-tooth forceps or snare can be used to facilitate the removal of the stent, reducing the risk of mucosa injury during removal[29]; (5) An overtube may be used to protect the esophageal mucosa while retrieving the stent with a rat-tooth grasper[30].

Figure 1 Endoscopic removal.

A: Rat-toothed grasper inside the biliary stent pusher; B: Stent border constrained by the grasper and pusher together.

Enteroscopy can be used to attempt removal of a stent migrated beyond the duodenum. Kohli et al[31] described the use of double-balloon enteroscopy to retrieve a self expandable plastic esophageal stent migrated through a Roux-en-Y anastomosis into the distal small intestine. In general, stents migrated beyond the reach of an endoscope should be observed with serial radiographs and physical examination.

PREVENTING ESOPHAGEAL STENT MIGRATION

Use of larger diameter stents (25-28 mm) may reduce the risk of migration, as suggested by two studies with migration rates varying from 8%-15%[32,33]. However, larger stents can increase the risk of stent-related complications involving the esophagus, such as hemorrhage, perforation and fistula[33-35].

New stent designs were developed with the intent to reduce migration. The Niti-S stent (Taewong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) has a double layer configuration, with an inner polyurethane layer to prevent tumor ingrowth and an outer uncovered nitinol-wire mesh, which was designed to embed into the esophageal wall and reduce migration (Figure 2). In a study with 42 patients, Verschuur et al[36] demonstrated low migration (7%) and ingrowth rates (5%) with this stent. In a series with 48 patients, Kim et al[37] showed a low migration rate (2%), but a high stent dysfunction rate caused by tumor overgrowth (27.1%). Another novel design, fully covered metal stent (Hanarostent Skidpoof; M.I. Tech Co, Pyeongtaek, South Korea) was described by Ji et al[38]. This stent has multiple protuberances on its body designed to be separate from the inner silicone membrane so that they can embed into the mucosa. The authors compared the new stent with a regular fully covered stent in dogs and showed a lower migration rate with the new stent (100% vs 55%, P = 0.035).

Figure 2 The Niti-S stent has a double-layered configuration.

The inner covered layer protects against tumor ingrowth and the additional uncovered mesh helps to resist migration.

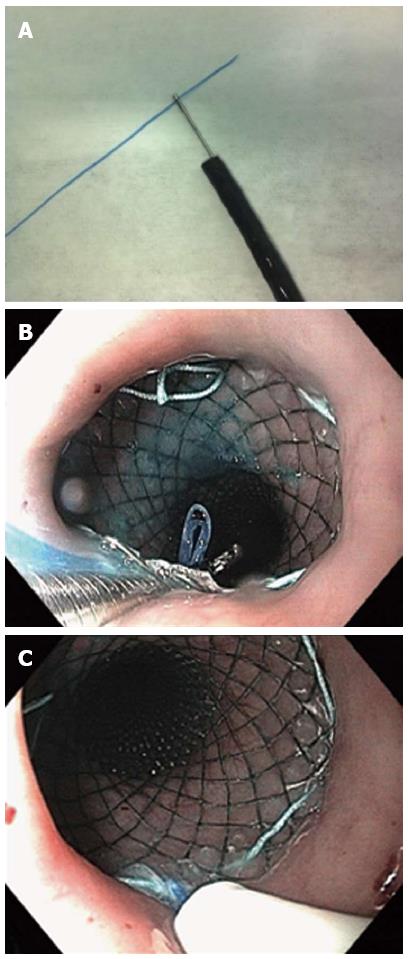

Some techniques of stent fixation have been described preventing migration. Shim’s technique consists of a modified covered metallic stent designed with a silk thread attached at the edge of the proximal end of the stent (HanarostentTM; M.I. Tech Co, Pyeongtaek, South Korea). After stent deployment, the thread is fixed to the patient’s nose or ear lobe by tape. The stent also has a proximal uncovered flange that allows tissue embedment. Endoscopy is repeated 2 wk after fixation and, if the stent is embedded in the esophageal mucosa and does not separate from the esophagus with air insufflation, the external fixation is removed. Using this technique, Shim et al[39] reported no migration in 61 patients. If stents with Shim’s technique are not available, a modified technique can be used[40]. A length of dental floss or equivalent thread is grasped with a biopsy forceps and passed through the working channel of a standard endoscope (Figure 3). The endoscope is positioned at the upper border of the stent and the forceps is passed through the stent mesh from outside to inside and advanced, carrying down the floss. The forceps is retrieved, leaving the floss down at the stent. The endoscope is advanced through the stent and the floss is grasped and gently brought back to the mouth, avoiding stent dislodgment. The floss is passed inside a nasoenteric soft tube to protect the nasopharyngeal mucosa. In addition to the silk and dental floss technique, other external stent fixation devices described have included umbilical tape[41] and snare[42].

Figure 3 A length of dental floss or equivalent thread is grasped with a biopsy forceps and passed through the working channel of a standard endoscope.

A: The dental floss is grasped with a biopsy forceps; B: The dental floss is passed through the stent mesh from the outside to the inside and carried down using the biopsy forceps; C: The dental floss is inserted into a nasoenteral tube, which is pushed down towards the mesh to protect the nasopharyngeal mucosa.

Fixation of the proximal flare of the stent to the esophageal mucosa with clips may be useful to avoid stent migration (Figure 4). Kato et al[43] reported no migration in nine patients with stent fixation with clips (three with strictures and six with digestive-respiratory fistula). In a series of 44 patients, fixation of the upper flare end of the stent to the esophageal mucosa with clips reduced migration rates of fully covered stents from 34% to 13% (3 out of 23 patients)[44].

Figure 4 Endoscopic clips may be applied at the upper border of the stent to prevent migration.

Recently, a small pilot study described successful stent fixation using an overstitch endoscopic suturing device (Apollo Endosurgery, Inc., Austin, TX, United States). This device can make interrupted or continuous stitches of various lengths and each stitch is finished with intracorporeal knot tying[45].

CONCLUSION

Esophageal stent placement is a safe and effective procedure to palliate dysphagia in patients with esophageal cancer, as well as to treat benign conditions such as esophageal strictures, fistulas and perforation. Migration is the most common complication after stent placement, especially with fully covered stents, but can be prevented by adequate stent selection and external or internal stent fixation. Migrated stents should be removed or repositioned whenever possible. Constriction of the proximal flare is the most important step for stent removal and forceps, snare and loops can be used individually or in combination to achieve adequate constriction. Endoscopic removal of the migrated stent is a low-morbidity procedure.

P- Reviewers: Braden B, Bordas JM, Koh PS, Murata A S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Zhang DN