Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.630

Revised: October 8, 2014

Accepted: October 28, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 131 Days and 5.9 Hours

A 57-year-old woman previously diagnosed with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) reported hematemesis. BRBNS is a rare vascular anomaly syndrome consisting of multifocal hemangiomas of the skin and gastrointestinal (GI) tract but her GI tract had never been examined. An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a large bleeding esophageal hematoma positioned between the thoracic esophagus and the gastric cardia. An endoscopic injection of polidocanol was used to stop the hematoma from bleeding. The hematoma was incised using the injection needle to reduce the pressure within it. Finally, argon plasma coagulation (APC) was applied to the edge of the incision. The esophageal hematoma disappeared seven days later. Two months after the endoscopic therapy, the esophageal ulcer healed and the hemangioma did not relapse. This rare case of a large esophageal hematoma originating from a hemangioma with BRBNS was treated using a combination of endoscopic therapy with polidocanol injection, incision, and APC.

Core tip: A patient with a large hemorrhagic esophageal hematoma complicated with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome was treated using endoscopic injection with polidocanol and incision with an injection needle. The hematoma was then treated with argon plasma coagulation.

- Citation: Takasumi M, Hikichi T, Takagi T, Sato M, Suzuki R, Watanabe K, Nakamura J, Sugimoto M, Waragai Y, Kikuchi H, Konno N, Watanabe H, Obara K, Ohira H. Endoscopic therapy for esophageal hematoma with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 6(12): 630-634

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v6/i12/630.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v6.i12.630

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare vascular anomaly syndrome consisting of multifocal hemangiomas of the skin and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. GI bleeding is a frequent complication that often presents with anemia as a result of chronic occult blood loss. Mortality depends on the GI involvement because it is difficult to treat GI bleeding. The use of endoscopic treatment of GI bleeding for hemangiomas has been reported[1,2]. We treated a single case of a large esophageal hematoma caused by a hemangioma. The treatment involved endoscopic injection, incision of the hematoma using an injection needle, and argon plasma coagulation (APC).

A 57-year-old woman was diagnosed with BRBNS because of skin hemangiomas since teen. However, her GI tract had never been examined. The patient had no anemia that suggested occult GI bleeding. She had no other history and did not take any drugs, including anti-thrombotics. In July 2011, she was admitted to a previously attended hospital complaining of hematemesis. An upper GI endoscopy showed a bleeding esophageal hematoma from the thoracic esophagus to the gastric cardia. We treated with total parenteral nutrition and nothing by mouth before endoscopic treatment, however, her anemia progressed. She was referred to our hospital because her hematoma had suspected esophageal or gastric varices.

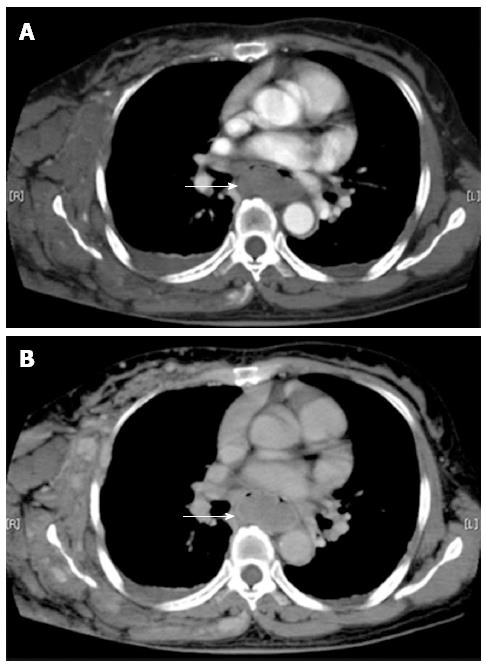

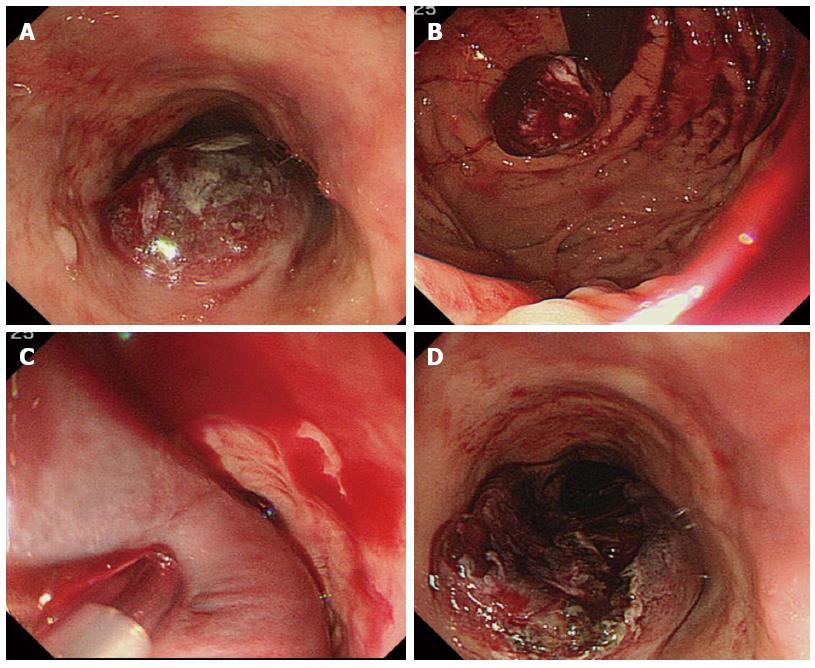

A physical examination at admission revealed a scar on her left breast from hemangioma resection and multiple bluish hemangiomas on her left arm (Figure 1). She had a height of 154 cm and a weight of 60 kg. The patient’s vital signs were stable: blood pressure 120/72 mmHg, heart rate 92 beats per minute, body temperature 36.3 °C, and SpO2 100% (room air). Laboratory data showed anemia, with a hemoglobin level of 7.4 g/dL. However, a mean corpuscular volume 95.6 fl suggested no chronic bleeding. The patient’s white blood cell count, liver function, renal function, and electrolyte balance were normal. The blood urea nitrogen/creatinine ratio was normal. The D dimer level was high (101.7 μg/mL) because of hypercoagulation in multiple hemangiomas. Dynamic computed tomography (CT) revealed an esophageal hematoma but no marked hemoperfusion to the hematoma (Figure 2). Upper GI endoscopy showed a growing esophageal hematoma with oozing bleeding (Figure 3A and B). The hematoma was large and bulging, and it was difficult to pass the endoscope over the hematoma. We inferred that this hematoma originated from hemangiomas related to BRBNS and that the hematoma had slow inflow from vessels such as esophageal varices because it had grown since it was identified at the other hospital. The patient had no history of vomiting, abdominal straining after excessive eating and drinking.

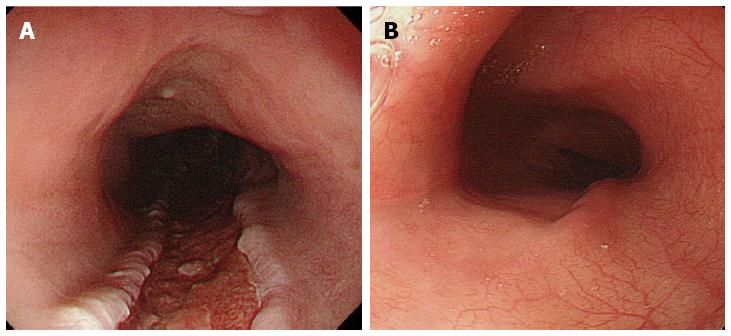

We first used endoscopic injection with polidocanol (aethoxysclerol; ASKA Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.) as a sclerosant for endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) for esophageal varices. This agent was used to obstruct the inflow vessels to the hematoma because it was dependent on esophageal varices. Twenty-four ml of 1% polidocanol was injected into the hematoma using a 23 G injection needle (Varixer; TOP Corp., Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 3C). Ten minutes after polidocanol injection, the hematoma was incised using the same injection needle to reduce the pressure within it (Figure 3D). Finally, argon plasma coagulation (APC: APC300; Amco Corp., Tokyo, Japan) was applied to the edge of the incision. We finished the endoscopic procedure because no active bleeding or oozing from the hematoma occurred. The patient received six units of transfused blood. Seven days after the treatment, upper GI endoscopy showed that the hematoma had disappeared (Figure 4A). The anemia did not progress. A liquid diet was started and was increased gradually to solid food. Ten days after endoscopic therapy, colonoscopy (CS) and capsule endoscopy (CE) were performed to check other hemorrhagic lesions and hemangiomas related to BRBNS in the small intestine and colon. Although CS revealed no hemangiomas, CE revealed a bluish lesion that implied the existence of a hemangioma in the small intestine. Two months after the endoscopic therapy, the esophageal ulcer healed and the hemangioma did not relapse (Figure 4B).

BRBNS is a rare disease associated with multiple rubbery cavernous hemangiomas on the skin and GI tract mucosa. Bean[3] first described BRBNS with cutaneous and GI malformations in 1958. The incidence of this syndrome is very low, and only approximately 200 cases have been described in the literature[4]. Histologically, BRBNS hemangiomas correspond to venous malformations. Vascular malformations are similar to hemangiomas and consist of abnormal vascular channels lined with a single layer of dysplastic endothelium. However, these lesions do not regress the way hemangiomas do. Vascular malformations are present at birth and are congenital[5]. They consist of mature endothelial-lined channels with insufficient surrounding smooth muscle[6]. For convenience, we use the words “hemangioma” to describe both vascular malformations and hemangiomas in this case report. Hemangiomas related to BRBNS have no malignant potential. However, the most important clinical concern is the high probability of fatal GI bleeding or chronic severe anemia[1]. The GI involvement in BRBNS is typically minimal, circumscribed, and multifocal[6]. The most common site of bowel involvement in BRBNS is the small intestine. In the case described in this study, CE revealed suspected hemangiomas. An upper GI endoscopy revealed a large intramural hematoma, but no hemangioma. The exact pathogenesis of the intramural hematoma in the esophagus is unclear. Intramural esophageal hematomas are generally characterized by a hemorrhagic episode that starts within the submucosa of the esophagus. Vomiting and abdominal straining, prior endoscopic procedures, and bleeding disorders are the common predisposing factors[7]. We were unable to prove that the hematoma had originated from a hemangioma due to BRBNS because the patient’s GI tract was not examined. However, we inferred that the large hematoma was related to the hemangiomas related to BRBNS because no other trigger such as vomiting or excessive eating or drinking was found.

EIS has been widely used to treat esophageal varices. We first considered that the pathology of the large hematoma was similar to esophageal varices. Intramural hematoma of the esophagus is reportedly a rare complication after EIS[8,9]. An intramural hematoma after EIS is an iatrogenic complication. It is formed by blood inflow because of faulty EIS. The use of an incision to treat the intramural hematoma after EIS was needed to reduce the pressure of the large hematoma and prevent its growth[9]. Although CT did not reveal inflow vessels to the hematoma in this case, we inferred that the hematoma was enlarged by slight and slow inflow from esophageal vessels. We selected endoscopic injection using polidocanol before incision to obstruct the inflow vessels to the hematoma and prevent the risk of bleeding. The hematoma was then incised using the same injection needle after confirmation that there was no bleeding from the pinhole or hematoma growth. Finally, APC was applied to the edge of the incision to stop any oozing bleeding that occurred after the incision. The presence of oozing bleeding after the incision suggested there was slow inflow to the hematoma. Seven days after endoscopic treatment of the hematoma, upper GI endoscopy showed that it had disappeared. The combination treatment consisting of endoscopic therapy, polidocanol injection, incision, and APC was effective.

An intramural hematoma of the esophagus might resolve spontaneously without therapeutic intervention and have a benign course[8]. However, the hematoma in this patient expanded and was growing. Symptom relief was rapid after incision of the hematoma. The patient was able to resume eating sooner than might have been predicted based on prior reports[7-11]. Following conservative therapy, symptoms usually begin to resolve 36-72 h after treatment and disappear completely in 2-3 wk[8]. The start of oral intake was sooner than previous cases[9-11]. It was possible for our patient to resume oral intake three days after the endoscopic incision, although it took approximately one week with conservative therapy in other studies[7,8]. In conclusion, a large esophageal hematoma from a bleeding hemangioma with BRBNS was treated using endoscopic techniques. It is noteworthy that an incision of the hematoma prevented its growth. This method is regarded as applicable not only to hematoma with BRBNS but also to hematomas with other GI diseases.

A 57-year-old woman previously diagnosed with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) reported hematemesis.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a bleeding esophageal hematoma from the thoracic esophagus to the gastric cardia.

Esophageal varices and intramural hematoma of the esophagus.

Laboratory data showed anemia with a hemoglobin level of 7.4 g/dL; however, mean corpuscular volume 95.6 fL suggested no chronic bleeding.

Dynamic computed tomography revealed an esophageal hematoma but no marked hemoperfusion to the hematoma.

No histological examination was done in this case.

Endoscopic treatment of polidocanol injection was applied, with incision by injection needle and argon plasma coagulation to the hematoma.

The incidence of BRBNS is very low. Approximately 200 cases have been described in the literature. Moreover, very few cases of intramural hematoma of the esophagus treated with endoscopy have been reported in the literature. Their treatment is controversial.

It is noteworthy that an incision of the hematoma prevented its growth. This method is regarded as applicable not only to hematoma with BRBNS but also to hematomas with other GI diseases.

This case demonstrates that treatment of esophageal intramural hematoma using endoscopic techniques was more effective than conservative therapy to relieve her symptoms rapidly.

The authors have described a case of esophageal hematoma with BRBNS that was treated using endoscopic techniques. The article describes novel treatment applied to an intramural hematoma of the esophagus.

| 1. | Hernandez OV, Blancas M, Paz V, Moran S, Hernandez L. Diagnosis and treatment of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome with double balloon enteroscopy and endoscopic ultrasound. Dig Endosc. 2007;19:86-89. |

| 2. | Ng EK, Cheung FK, Chiu PW. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: treatment of multiple gastrointestinal hemangiomas with argon plasma coagulator. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:40-42. |

| 3. | Bean WB. Blue rubber bleb naevi of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in vascular spiders and related lesions of the skin. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas 1958; 178-185. |

| 4. | Dobru D, Seuchea N, Dorin M, Careianu V. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: case report and literature review. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004;13:237-240. |

| 5. | Elsayes KM, Menias CO, Dillman JR, Platt JF, Willatt JM, Heiken JP. Vascular malformation and hemangiomatosis syndromes: spectrum of imaging manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:1291-1299. |

| 6. | Fishman SJ, Smithers CJ, Folkman J, Lund DP, Burrows PE, Mulliken JB, Fox VL. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: surgical eradication of gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Surg. 2005;241:523-528. |

| 7. | Hong M, Warum D, Karamanian A. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma (IEH) secondary to anticoagulation and/or thrombolysis therapy in the setting of a pulmonary embolism: a case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2013;7:1-10. |

| 8. | Van Beljon J, Krige JE, Bornman PC. Intramural esophageal hematoma after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for bleeding varices. Dig Endosc. 2004;16:61–65. |

| 9. | Adachi T, Togashi H, Watanabe H, Okumoto K, Hattori E, Takeda T, Terui Y, Aoki M, Ito J, Sugahara K. Endoscopic incision for esophageal intramural hematoma after injection sclerotherapy: case report. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:466-468. |

| 10. | Cho CM, Ha SS, Tak WY, Kweon YO, Kim SK, Choi YH, Chung JM. Endoscopic incision of a septum in a case of spontaneous intramural dissection of the esophagus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35:387-390. |

| 11. | Sudhamshu KC, Kouzu T, Matsutani S, Hishikawa E, Saisho H. Early endoscopic treatment of intramural hematoma of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:297-301. |

P- Reviewer: Kakushima N, Seicean A, Vernimmen FJ S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN