Endoscopic submucosal dissection

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is an established technique for resection of gastric or colorectal neoplasms. After circumferential mucosal incision, step-by-step dissection of submucosal and muscular fibres with different electrosurgical knifes allows precise en-bloc resection of tumors. The technique has been used for resection of SET originating from the MP. In this context, it has also been called “endoscopic muscularis dissection”, “endoscopic enucleation” or “endoscopic submucosal excavation”[10,17,18]. The largest study in this field was recently published by a He and colleagues. 145 patients with gastric SET arising from the MP with an average diameter of 15.14 mm (range 3-50) underwent ESD. Complete resection rate was 92%. Perforation occurred in 14%, all of which could be managed endoscopically[19]. A Chinese study included 143 patients with SET of the esophagogastric junction arising from the MP. Histologically complete en bloc resection could be achieved in 94.4%, perforation rate was 4.2%[20]. Other studies report success rates of 68%-100% with perforation rates of 2.4%-13.3%[21-26]. In conclusion, ESD appears to be an effective technique for resection of SET up to a size of 50 mm. However, the technique is technically demanding and may be time consuming. Moreover, for tumors arising from the MP, perforation rates up to 15% even in experienced hands have been reported. Lesions fixed to to the MP exhibit an increased risk of perforation when compared to lesions with a positive rolling sign[22]. Although extent of connection to the MP has not shown to be associated with increased risk of perforation[22], thorough EUS evaluation is mandatory prior treatment.

Submucosal endoscopic tumor resection/submucosal tunneling

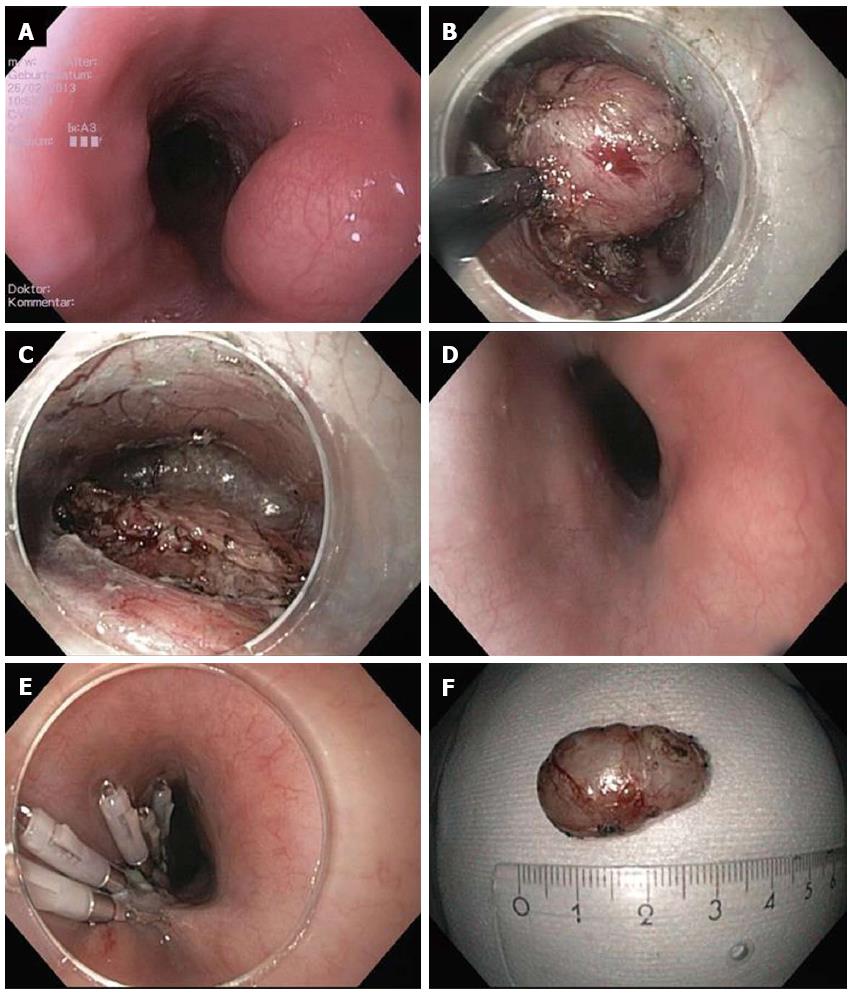

The concept of “submucosal tunnelling” in the esophagus was initially described for peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) procedure by Inoue et al[27] in 2010. Only a few years later, this technique was applied for resection of subepithelial tumors in the esophagus and in the cardia[28,29]. In analogy to the POEM procedure, a mucosal incision at least 5 cm proximal to the tumor is created and the endoscope is introduced into the submucosal space. Then, the submucosal fibres are dissected until the tumor gets visible in the tunnel. The tumor is subsequently enucleated in ESD technique. During tunnelling and enucleation, it is crucial not to perforate the mucosa. After extracting the tumor from the tunnel, the mucosal incision is finally closed with standard clips (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Submucosal endoscopic tumor resection/tunneling technique.

A: Endoscopic image of lumen obstruction subepithelial tumor in the proximal esophagus in a 42 years old woman with dysphagia; B: After preparing the submucosal tunnel, the tumor gets visible and is enucleated in endoscopic submucosal dissection-technique with a TT knife. The tumor was arising from the muscularis propria; C: Resection site (endoscope in the submucosal tunnel). The muscularis propria is excised/perforated; D: Resection site (endoscope in the esophageal lumen. Intact mucosa completely covers the muscular perforation; E: The mucosal incision (about 5 cm proximal tot he resection site) was closed with standard clips; F: Resection specimen. Histological examination revealed a Leiomyoma, which had been R0-resected.

Submucosal endoscopic tumor resection is especially suitable for tumors originating from or infiltrating into the MP. Compared to conventional ESD, a major advantage of this novel technique is that a mucosal layer covers the resection site and protects from mediastinitis/peritonitis when intended or accidental perforation of the MP occurs.

The largest study published to date included 85 SET (60 esophageal and 9 gastric). The tumors were mainly arising form the superficial MP (88.2%) and had a mean size of 19.2 mm (range 10-30 mm). Complete resection was achieved in 100% of cases with a mean procedure time of 57.2 min. Pneumothorax occurred in 7.1%, subcutaneous emphysema in 9.4% and pneumoperitoneum im 4.7%[30]. Other smaller studies reported success rates between 78% and 100% and complication rates between 13% and 33%[18,29,31,32]. The most common complications reported are pneumothorax, subcutaneous and mediastinal emphysema and pneumoperitoneum. While occurrence of pneumothorax generally requires a chest drain, air leakage into the mediastinum, the abdominal cavity and the subcutaneous tissue may not be considered as a “complication” rather than a natural consequence when the MP is perforated/resected. As long as the covering mucosa over the perforation is preserved, leakage of esophageal or gastric content is prevented. In the clinical studies published to date, no severe intraabdominal or mediastinal infections have been reported. Hence, submucosal endoscopic tumor resection using a tunnelling technique is feasible and relatively safe for tumors originating from the MP in the esophagus and cardia. Although a few gastric cases are also reported, submucosal tunnelling requires a relatively straight endoscope position and may not be applicable for tumors in locations like the fundus or proximal corpus.

Endoscopic full thickness resection

For SET arising from or infiltrating deep layers of the MP, full thickness resection may be necessary to achieve complete removal of the tumor. As full thickness resection naturally results in a GI wall perforation, secure and effective defect closure is mandatory. Generally, there are two different approaches for endoscopic full thickness resection (EFTR): (1) Full thickness resection followed by endoscopic defect closure; and (2) Creation of GI wall duplication (with serosa-to-serosa apposition) followed by EFTR.

Zhou et al[33] reported full thickness resection of 26 gastric SETs arising from the MP. Resection/enucleation of the tumors was performed using ESD technique and the gastric wall defect was closed with standard clips. Mean tumor size was 2.8 cm (1.2-4.5 cm). Complete resection rate was 100% with a mean procedure time of 105 min; no major complications were reported. Another study from 2013 reported 20 on a similar resection technique in 20 patients. In this study, the wall defects were closed with clips and endoloops[34]. En bloc resection rate was 100% without severe complications. A Chinese study reported on 42 gastric stromal tumors which were resected either by EFTR with secondary clip closure or laparascopically. In this non-randomized study, complete resection rate, operation time, length of hospital stay and complications were not statistically different in both groups[35].

Although the studies mentioned report excellent results with no serious complications, it must be emphasized that defect closure with standard clips may only be possible for small perforations. Moreover, concerns have been raised whether closure of only the mucosal layer is sufficient after EFTR[36]. Von Renteln and colleagues compared closure of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) gastrostomies by either conventional or over-the-scope clips (OTSC) in a porcine study with 20 pigs[37]. In the conventional clip group, 3 minor and 1 major leaks were observed and four pigs developed peritonitis. In the OTSC group, no leaks were observed and microscopic evaluation showed that OTSC led to a deeper defect closure within the submucosal or muscular layer. Multiple clinical studies have shown effectivity of OTSC for durable closure of GI wall perforations[38]. EFTR with consecutive defect closure with OTSC was clinically evaluated in the EndoResect study[39]. Twenty patients with gastric SET ≤ 3 cm were enrolled; six tumors could not be resected endoscopically due to large size or extraluminal growth. The other tumors were resected using a double channel endoscope, a tissue retractor and a monofilament snare. Perforation occurred in six cases, all of which could be closed by OTSC application; mean procedure time was 44 min. Although this approach is very interesting because of its technical simplicity, most of the procedures in the study were done under laparoscopic control. Moreover, OTSC application requires secure apposition of the borders of the gastric defect which may not be possible in case of large perforations.

Even if clinical data suggest that EFTR with secondary defect closure is feasible and safe, secure closure of the GI wall may be technically demanding and strongly depends on the skills and the experience of the endoscopist[10]. Therefore, securing GI wall patency before resection (in analogy to laparoscopic wedge resection) may be an interesting and potentially safer approach. The concept of OTSC application over a SET followed by snare resection above the clip was recently reported by a United States group[40,41]. Lesions were located in the duodenum, in the esophagus, in the stomach and in the rectum. After application of an 11 mm OTSC, all lesions could be resected successfully. R0-resection was achieved in 7/8 cases. A drawback of this technique is that the size of the cap limits the maximum size of the lesion (mean size in the study was 13.4 mm). A novel over-the-scope device (FTRD, Ovesco Endoscopy) uses a modified 14 mm OTSC mounted on a long transparent cap with a preloaded snare (Figures 2 and 3)[42-45]. This device has been designed for one-step full thickness resection using a clip-and-cut technique. Due to the larger diameter of the OTSC and the longer cap, resection of larger lesions is possible compared to the standard OTSC system. The device was investigated by von Renteln et al[44] for resection of artificial submucosal lesions in a porcine study. The OTSC was able to close the resection site completely in all cases, however, EFTR was achieved in 50% of cases only. This is probably due to the fact that the thick gastric wall can often not fully be incorporated into the cap with its inner diameter of 13 mm. Another drawback of the device is its large outer diameter of 21 mm which hampers peroral introducability. Two porcine studies evaluated the device for use in the colon and showed that EFTR was feasible with efficient OTSC closure of the defects. Maximum size of resection specimen was 30 and 40 mm. In our first clinical experience (25 patients, manuscript submitted), colorectal EFTR with the FTRD was effective and safe. Due to the limitations in the upper GI tract, the FTRD is currently CE marked exclusively for colorectal EFTR.

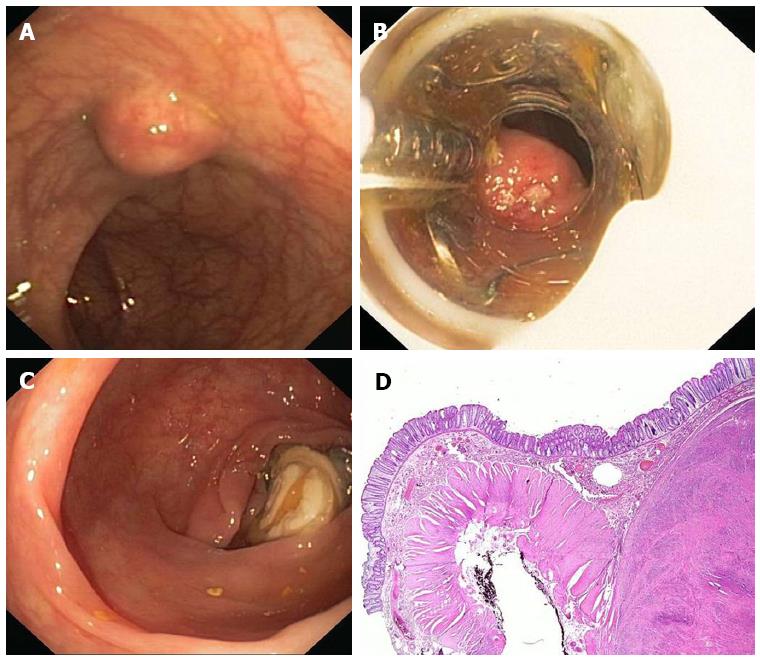

Figure 2 FTRD (Full Thickness Resection Device, Ovesco Endoscopy, Tübingen Germany).

The device is assembled on a standard colonoscope. It consists of 14 mm modified over-the-scope clips which is mounted on a long transparent cap. A monofilament snare is preloaded in the tip of the cap. The handle of the snare runs on the outer surface of the endoscope underneath a transparent sheath. A grasping forceps or a tissue anchor can be advanced through the working channel of the endoscope.

Figure 3 Endoscopic full thickness resection with the FTRD.

A: A 75 years old woman presented with a 1.5 cm subepithelial tumor in the descending colon; B: Endoscopic view with the FTRD mounted on a standard colonoscope; C: Resection site after endoscopic full thickness resection. The over-the-scope clips secures colonic wall patency; D: Histologic image (HE-staining) of the resection specimen showing one lateral resection margin. Note the cross-sectional view of the whole colonic wall on the left side. The tumor (leiomyoma) is shown on the right.

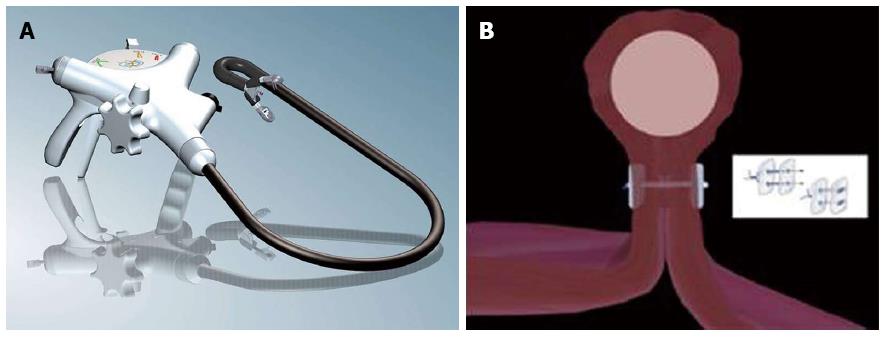

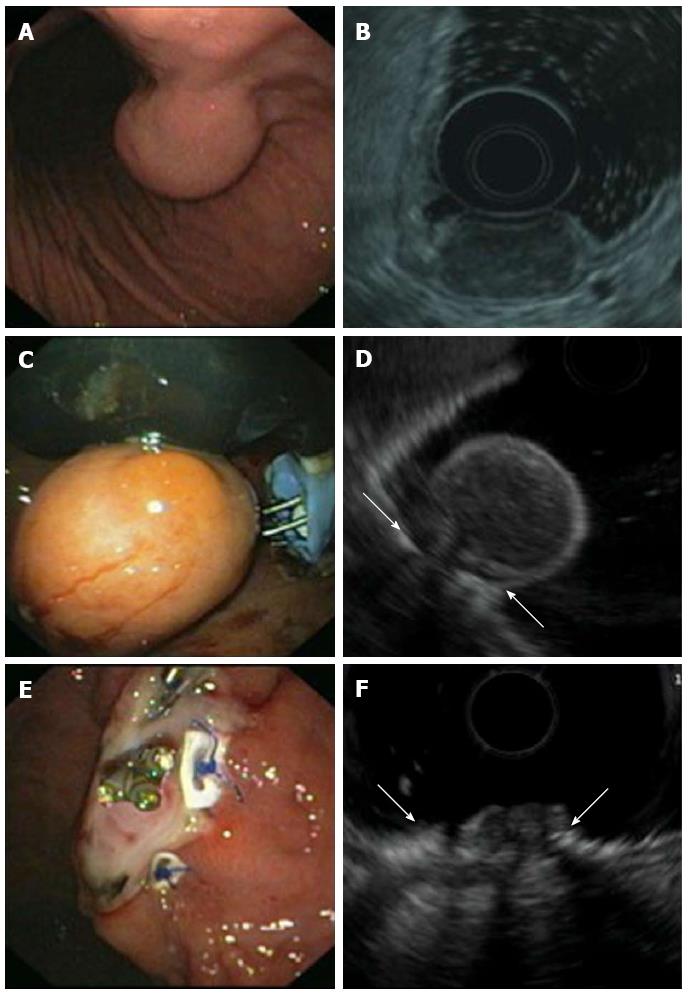

In 2008, our group reported on the concept of applying transmural sutures underneath the tumor prior EFTR for the first time. Two transmural PTFE-pledgeted sutures were placed underneath the tumor using a device originally designed for endoscopic anti-reflux Therapy (PlicatorTM, NDO Surgical, Inc, Mansfield, Mass) thereby creating a full thickness duplication with serosa-to-serosa apposition (Figure 4). The tumor was then resected with a monofilament snare above the suture (Figure 5)[46]. In 2011, a second series with three patients undergoing successful EFTR with the use of resorbable sutures was published[47]. In the meantime, our group has applied this technique for EFTR of subepithelial gastric tumors in a total of 31 patients [Schmidt et al, manuscript accepted in Endoscopy]. Mean tumor size was 20.5 mm (range 8-48). Macroscopically complete en bloc resection could be achieved in 100%, R0-resection rate was 90.3% with a median procedure time of 60 min. Perforation occurred in three patients; in all cases, the defect was successfully closed by application of additional transmural sutures. When compared to OTSC application before resection, this method is applicable for tumors up to a size of about 4 cm. Moreover, it is feasible in almost every location in the stomach. As the suturing device was originally designed to work in retroflex position, the technique is especially suitable for tumors in the proximal corpus, cardia and even in the fundus. In comparison to the clip closure techniques described above, patency of the gastric wall is secured not only by mucosal closure but rather by full-thickness suturing with serosa-to-serosa apposition. This technique meets surgical standards for defect closure and may result in a more durable gastric wall repair especially for resection of large tumors. The suturing device can not only be used for suturing prior resection but also for secondary perforation closure[48]. A major limitation of EFTR after transmural suturing is the need of special endoscopic equipment. The PlicatorTM device from NDO is not any more commercially available. However, a new CE-marked single-use device is available in Europe now (GERDXTM, G-Surg, Seeon, Germany). This device was used for the last two cases in our series and seems to be as effective as the PlicatorTM.

Figure 4 Endoscopic full thickness suturing.

A: The GERDX suturing device (G-Surg, Seeon, Germany); B: Schematic illustration of full thickness suturing. Application of PTFE-pledgeted sutures underneath the tumor creates a gastric wall duplication with serosa-to-serosa apposition.

Figure 5 Endoscopic full thickness resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors after transmural suturing.

A: Subepithelial tumor in the gastric corpus; B: Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed a hypoechoic tumor originating from the muscularis propria with a maximum diameter of 27 mm; C: Two transmural sutures underneath the tumor were applied using the PlicatorTM suturing device; D: EUS image of the pseudopolyp after suturing. Arrows are indicating the sutures; E: The tumor was resected with a snare above the sutures. The transmural PTFE-pledgeted sutures are securing gastric wall patency. Resection was macroscopically complete; F: EUS image of the resection site. Arrows are indicating the sutures. There was no evidence of residual tumor.