Published online Apr 16, 2013. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v5.i4.154

Revised: February 7, 2013

Accepted: February 28, 2013

Published online: April 16, 2013

Processing time: 264 Days and 9.9 Hours

AIM: To determine the test characteristics of community based video capsule endoscopy (VCE) in patients undergoing sequential VCE and double balloon enteroscopy (DBE).

METHODS: Eighty-nine patients (34 females, 55 males, mean age 66) who underwent both VCE and DBE from 2008-2010 were retrospectively reviewed. Lesions detected at VCE were categorized. Capsule directed DBE followed and included 44 antegrade, 11 retrograde and 34 combined antegrade and retrograde procedures. Lesions detected were compared utilizing the McNemar’s test.

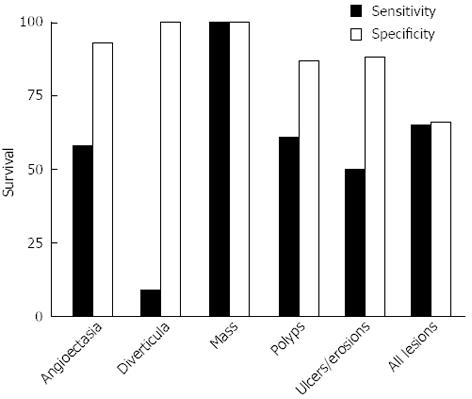

RESULTS: Angioectasia detection with VCE was 25% and with DBE 35% (P < 0.03) with a calculated sensitivity and specificity of 58% and 93% respectively. Polyps were detected by VCE in 22% and in DBE 20%, (P = 0.6), with a sensitivity and specificity for VCE of 61% and 87%. Small bowel diverticula were only seen in 1% of VCE but in 12% of DBE patients (P < 0.002) with a calculated sensitivity and specificity of VCE of 9% and 100%.

CONCLUSION: VCE would be moderately sensitive and specific overall with considerable variation by lesion. Furthermore, VCE cannot be relied upon to diagnose small bowel diverticula.

Core tip: Advances in endoscopic technology have revolutionized the evaluation of small intestinal disorders. Non-invasive imaging utilizing video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers the potential to safely visualize the entire small bowel with a high diagnostic yield. It is limited by a lack of therapeutic ability, imprecise localization, failure to reach the colon in all cases and inconsistent visualization of the entire small bowel. Deep enteroscopy, utilizing double balloon enteroscopy (DBE), enables diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy of the small bowel. Although total enteroscopy can be accomplished, it typically requires antegrade and retrograde approaches. In most clinical situations, VCE is performed initially. By using DBE as the criterion (gold) standard, the sensitivity and specificity of community based VCE can be assessed for individual lesions, offering a more informative comparison than diagnostic yield.

- Citation: Tenembaum D, Sison C, Rubin M. Accuracy of community based video capsule endoscopy in patients undergoing follow up double balloon enteroscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2013; 5(4): 154-159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v5/i4/154.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i4.154

Advances in endoscopic technology have revolutionized the evaluation of small intestinal disorders. Non-invasive imaging utilizing video capsule endoscopy (VCE) offers the potential to safely visualize the entire small bowel with a high diagnostic yield[1,2]. It is limited by a lack of therapeutic ability, imprecise localization, failure to reach the colon in all cases and inconsistent visualization of the entire small bowel[3]. Deep enteroscopy, utilizing double balloon enteroscopy (DBE), enables diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopy of the small bowel. Limitations of DBE include its invasive nature, limited availability and the need for anesthesia[4]. Although total enteroscopy can be accomplished, it typically requires antegrade and retrograde approaches. The rate of total enteroscopy varies between 11%-66%[5,6]. In most clinical situations, VCE is performed initially[3]. The results can then be used to determine the need for deep enteroscopy as well as the entry route (antegrade or retrograde)[7,8]. Studies comparing the relative abilities of VCE and DBE, are based on “diagnostic yield” which refers to the proportion of examinations in which any abnormality is detected. Two recent meta-analyses of studies comparing VCE and DBE have demonstrated comparable diagnostic yields[1,2]. Few studies, however, compared the individual abnormalities detected at VCE with those subsequently confirmed at DBE[9]. We propose to evaluate the test characteristics of VCE for each type of lesion by comparing the results of community based VCE to the findings at follow up DBE for each patient. By using DBE as the criterion (gold) standard, the sensitivity and specificity of community based VCE can be assessed for individual lesions, offering a more informative comparison than diagnostic yield.

Eighty-nine patients, 34 females and 55 males with a mean age of 66, who underwent sequential VCE and DBE exams between 2008-2010 were retrospectively reviewed (Table 1). The study was approved by the New York Hospital Queens institutional review board. All VCE studies but one were performed with the Given Imaging Pillcam SB2® system. VCE studies were read by both community and full-time academic gastroenterologists in the New York metropolitan area. A formal second review of VCE studies by a single expert was not performed. Preparation for VCE was variable and depended on the preferences of the referring physician. Findings were not correlated with use and type of preparation. No attempt was made to correlate VCE findings with pre-procedure preparation since the effect of preparation on diagnostic yield remains controversial[10-12]. All patients undergoing antegrade DBE were NPO for eight hours prior to the exam. All patients undergoing retrograde DBE were prepped with a combination of 2 L of polyethylene glycol and Bisacody l20 mg.

| Total patients | 89 |

| Male | 55 (62) |

| Female | 34 (38) |

| Median days from VCE to DBE | 29 (8-64) |

| Age (range) (yr) | 66 (19-93) |

| Antegrade DBE | 44 (49) |

| Retrograde DBE | 11 (12) |

| Antegrade and retrograde DBE | 34 (38) |

DBE studies were performed with the Fujinon EN-450T5 enteroscope with a methodology described previously[13]. All DBE procedures were performed by one attending (MR) and a gastroenterology fellow at New York Hospital Queens Weill-Cornell Medical College. The approach to DBE was guided by VCE findings. Patients with positive VCE findings in the proximal and mid small-bowel underwent antegrade DBE initially. If the lesion was not found, a retrograde procedure was then performed. Patients with lesions seen in the distal small bowel at VCE underwent a retrograde DBE as the initial procedure. If the lesion was not found, an antegrade procedure was then performed. In total 44 patients underwent antegrade DBE, 11 retrograde DBE and 34 underwent both. Sixteen of the 34 had complete enteroscopy[5,6]. In patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and negative VCE exams, DBE was guided by the patient’s history. A second DBE was only performed if no lesion was found. The median time interval between the performance of VCE and the initial DBE was 29 d.

Descriptive statistics such as means, SD, medians and interquartile range were used to characterize the age distribution and time between VCE and DBE. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV), along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals, were calculated to evaluate the accuracy of VCE for identification of lesions using DBE as criterion standard. McNemar’s test for paired data was used to compare detection rates between VCE and DBE. In addition to investigating detection rates for the overall presence of any lesion, separate analyses were also performed according to the type of lesion (angioectasia, diverticula, mass, polyps, ulcers/erosions). All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A result was considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level of significance.

Abnormalities identified by VCE and DBE were categorized into 5 groups to facilitate the comparison of VCE to DBE by lesion type. These groups include: (1) Angioectasia; (2) Diverticula; (3) Mass; (4) Polyps; and (5) Ulcers/Erosions.

Indications for VCE included OGIB (n = 78, 88%), suspicion of Crohn’s disease (n = 10, 11%), and suspicion of Whipples disease (n = 1, 1%).

The overall diagnostic yields of VCE and DBE were 64% and 66% respectively (P = 0.72). Diagnostic yield by lesion type showed a significantly higher detection rate for DBE in the detection of angioectasia and diverticula. Angioectasia detection by VCE was 25% compared to 35% for DBE (P = 0.03, Table 2). By location, 35% of angioectasias identified at VCE were in the first tertile, 43% in the second tertile and 22% in the third tertile. The vast majority of angioectasias (11/13) seen at DBE but not at VCE were in the proximal to mid-small bowel. Small bowel diverticula were seen in 1% of all VCE patients compared to 12% of DBE patients (P = 0.002). Diverticula were identified in the duodenum in 2 patients, jejunum in 7 patients and the ileum in 4 patients. Mass lesions were seen in two patients with VCE and both were confirmed at DBE. No additional mass lesions were discovered by DBE. Small bowel polyps were seen in 22% of VCE patients compared to 20% of DBE patients (P = 0.62). Small bowel ulcers were seen in 17% of VCE patients compared to 14% of DBE patients (P = 0.44) (Table 2).

| VCE | DBE | P value | |

| Angioectasia | 25% | 35% | 0.03 |

| Diverticula | 1% | 12% | 0.002 |

| Mass | 2% | 2% | NA |

| Polyps | 22% | 20% | 0.62 |

| Ulcers | 17% | 14% | 0.44 |

| All Lesions | 64% | 66% | 0.72 |

Comparison of VCE and DBE findings by lesion type: (1) Angioectasia: Angioectasias were found by both VCE and DBE in 18 patients. They were found only in VCE in 4 patients and in DBE alone in 13 patients; and (2) Diverticula: Small bowel diverticula were seen in both VCE and DBE in only 1 patient but were seen at DBE in 10 additional patients (Figure 1).

Two masses were seen by both VCE and DBE. Polyps were found by both VCE and DBE in eleven patients, at VCE and not DBE in 9 patients, and were seen at DBE and not VCE in 7 patients. Ulcers were found in both VCE and DBE in 6 patients, at VCE but not DBE in 9 patients, and were seen at DBE and not VCE in 6 patients (Table 3).

| Lesions | VCE+/DBE+ | VCE+/DBE+ | VCE+/DBE+ | VCE+/DBE+ | Sensitivity of VCE | Specificity of VCE | PPV | NPV |

| Angioectasia | 18 | 4 | 13 | 54 | 58% | 93% | 82% | 81% |

| Diverticula | 1 | 0 | 10 | 78 | 9% | 100% | 100% | 89% |

| Mass | 2 | 0 | 0 | 87 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| Polyps | 11 | 9 | 7 | 62 | 61% | 87% | 55% | 90% |

| Ulcers/erosions | 6 | 9 | 6 | 68 | 50% | 88% | 40% | 92% |

The sensitivity and specificity of VCE using DBE as the criterion standard varied by lesion type (Figure 2). Overall, the sensitivity of VCE was 65% and the specificity was 66%. VCE was most sensitive and specific for masses (100%). It was moderately sensitive (58%) but highly specific (93%) for angioectasia. The sensitivity for ulcers/erosions was 50% and the specificity was 88%. For polyps, the sensitivity and specificity was 61% and 87%. Importantly, VCE had very low sensitivity for detecting diverticulosis (9%) (Figure 2, Table 3).

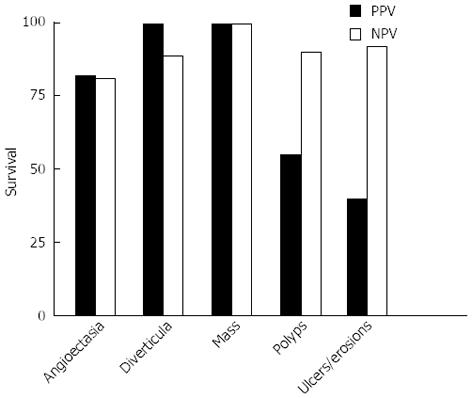

The positive and NPV of VCE by lesion were; Angioectasia 82% and 81% respectively; Diverticula 100% and 89% respectively; Mass 100% positive and NPV; Polyps 55.0% and 90% respectively; Ulcers/erosions 40% and 92% respectively (Figure 3, Table 3).

In our study of patients undergoing sequential VCE and DBE, the overall diagnostic yield of these two procedures was equivalent. This is consistent with prior studies[1,2]. However, when diagnostic yield was compared by lesion type, we found significant differences between VCE and DBE. DBE had a higher diagnostic yield for both diverticula and angioectasia.

Duodenal diverticula are reported in 5% of upper abdominal radiographs and up to 25% in patients undergoing ERCP or at autopsy[14]. Small bowel diverticula are less common but have been found in 0.5% to 5% of radiographs and autopsies[15,16]. In our study, 11 patients (12%) who were referred for DBE were found to have diverticula. However, only 1 of 11 was detected on VCE. The failure of VCE to diagnose small bowel diverticula has been noted previously. In 2008, Hussain et al[17] reported finding multiple diverticula in a patient undergoing DBE, which was not detected by VCE. In 2009, Fukumoto et al[18] reported finding an ileal diverticulum on DBE that was missed by VCE. Marmo et al[19] reported two missed jejunal diverticula that were later seen on subsequent DBE. Similarly, Arakawa et al[20] reported 2 cases of diverticulosis of the small bowel that were missed at previous VCE. In this larger series, the sensitivity of VCE for detecting diverticula was only 9%, confirming that VCE cannot be relied upon to make this diagnosis.

The diagnostic yield for angioectasia at DBE was significantly higher than VCE (35% vs 25%). Differences in angioectasia detection by VCE and DBE have been reported. Some studies found a higher detection rate at VCE while others found a higher rate at DBE. Fukumoto et al[18] described 2 patients that had angioectasia at VCE that were missed at subsequent DBE. Similarly, Arakawa reported 3 cases with missed angioectasia at DBE. Both studies attributed the missed lesions to incomplete DBE[18,20]. Angioectasia detected at DBE but not at VCE has also been described. Arakawa and Marmo each reported 2 VCE-negative DBE-positive cases[19,20]. None of these studies, however, assessed the test characteristics of VCE using DBE as the criterion standard. In our study, we found that VCE is highly specific but only moderately sensitive for detecting angioectasia (93% and 58% respectively). Since DBE detects a greater number of angioectasia, a negative capsule should not be viewed as conclusive. However, since not all red spots identified at DBE are true angioectasia, the clinical significance of the detection rate differences between VCE and DBE remains uncertain.

The diagnostic yield for polyp detection at VCE and DBE was statistically equivalent (22% and 20% respectively). However, using DBE as the criterion standard, the actual sensitivity of VCE was only 61% and the specificity was 87%. The low sensitivity implies that a significant number of lesions were missed at VCE. Alternatively some lesions thought to be polyps at VCE that were not confirmed at DBE may have been due to over interpretation of bulges and folds at VCE. The limitation of DBE however, was a lack of complete enteroscopy in all patients. Our approach of VCE directed deep enteroscopy is consistent with standard practice[3]. Nevertheless, these findings illustrate the limitation of relying on diagnostic yield as an overall measure of test accuracy. The same findings holds true for ulcers and erosions.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective design, interobserver variability in community based VCE interpretation[21], reliance on capsule directed deep enteroscopy rather than attempting complete enteroscopy in all patients and the likelihood of false positive and false negative results at DBE. Correlation of VCE findings with pre-procedure preparation was not assessed since the effect of preparation on diagnostic yield remains controversial[10-12]. Despite these limitations, we believe this data is significant and reflects the actual clinical practice of referring patients to specialized centers for deep enteroscopy based on the findings of community read VCE studies. Thus, the test characteristics described in this study may be unique to patients undergoing community based VCE followed by expert DBE and may not reflect the test characteristics of VCE in patients undergoing both studies at a tertiary care referral center. However, our study is reflective of real world practice and adds to our understanding of the benefits and limitations of these modalities.

In summary, our results suggest that comparing the diagnostic yield of VCE and DBE as a measure of test accuracy is misleading. By assessing the test characteristics of VCE utilizing deep enteroscopy as the criterion standard, we have demonstrated that VCE is moderately sensitive and specific in the diagnosis of patients with small bowel disease. VCE cannot, however, be relied upon to rule out small bowel diverticula. Furthermore, based on our findings, the currently accepted algorithm for the evaluation of patients with obscure bleeding[22] which currently recommends observation alone in patients with a negative VCE should be reconsidered.

Studies comparing video capsule endoscopy (VCE) and deep enteroscopy have shown equivalent diagnostic yields. Although both procedures yield similar numbers of abnormalities, the accuracy of VCE by lesion type utilizing double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) as the criterion standard has not been well defined.

The aim of this study is to determine the test characteristics of community based VCE in patients undergoing subsequent DBE and define the accuracy of VCE by individual lesion type.

The results of this study show that the detection rates for DBE and VCE were equivalent overall (66% vs 64%). However, detection rates were not equivalent when comparing individual lesions. DBE had a significantly greater detection rate for AVM’s (35% vs 25%, P = 0.03) and diverticulosis (12% vs 1%, P = 0.002). The sensitivity and specificity of VCE varies by lesion type.

VCE and DBE are complimentary procedures. In the community setting, VCE is typically performed initially in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and will help guide subsequent DBE. However, VCE has a low sensitivity for certain lesions, especially small bowel diverticula. Therefore, patients with negative VCE and obscure bleeding should undergo subsequent deep enteroscopy.

Diagnostic yield refers to the number of positive findings in each exam.

The manuscript is very valuable presenting a comparison of VCE with DBE in real life setting. Although the review is retrospective it offers a lot of new information mostly for the daily endoscopy practice.

| 1. | Teshima CW, Kuipers EJ, van Zanten SV, Mensink PB. Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Pasha SF, Leighton JA, Das A, Harrison ME, Decker GA, Fleischer DE, Sharma VK. Double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy have comparable diagnostic yield in small-bowel disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:671-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Leighton JA. The role of endoscopic imaging of the small bowel in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:27-36; quiz 37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy (push-and-pull enteroscopy) of the small bowel: feasibility and diagnostic and therapeutic yield in patients with suspected small bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:62-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 261] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, Lenz P, Meister T, Luegering A, Ullerich H, Aabakken L, Heinecke A, Domschke W. Single- vs. double-balloon enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2011;43:472-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | May A, Färber M, Aschmoneit I, Pohl J, Manner H, Lotterer E, Möschler O, Kunz J, Gossner L, Mönkemüller K. Prospective multicenter trial comparing push-and-pull enteroscopy with the single- and double-balloon techniques in patients with small-bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:575-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pasha SF, Hara AK, Leighton JA. Diagnostic evaluation and management of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a changing paradigm. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2009;5:839-850. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 379] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Li X, Dai J, Lu H, Gao Y, Chen H, Ge Z. A prospective study on evaluating the diagnostic yield of video capsule endoscopy followed by directed double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1704-1710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen HB, Huang Y, Chen SY, Song HW, Li XL, Dai DL, Xie JT, He S, Zhao YY, Huang C. Small bowel preparations for capsule endoscopy with mannitol and simethicone: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pons Beltrán V, González Suárez B, González Asanza C, Pérez-Cuadrado E, Fernández Diez S, Fernández-Urién I, Mata Bilbao A, Espinós Pérez JC, Pérez Grueso MJ, Argüello Viudez L. Evaluation of different bowel preparations for small bowel capsule endoscopy: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2900-2905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de Franchis R, Avgerinos A, Barkin J, Cave D, Filoche B. ICCE consensus for bowel preparation and prokinetics. Endoscopy. 2005;37:1040-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 896] [Cited by in RCA: 867] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Løtveit T, Skar V, Osnes M. Juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula. Endoscopy. 1988;20 Suppl 1:175-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Baskin RH, Mayo CW. Jejunal diverticulosis; a clinical study of 87 cases. Surg Clin North Am. 1952;1185-1196. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Rosedale RS, Lawrence HR. Jejunal diverticulosis. Am J Surg. 1936;34:369-373. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hussain SA, Esposito SP, Rubin M. Identification of small bowel diverticula with double-balloon enteroscopy following non-diagnostic capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2296-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fukumoto A, Tanaka S, Shishido T, Takemura Y, Oka S, Chayama K. Comparison of detectability of small-bowel lesions between capsule endoscopy and double-balloon endoscopy for patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:857-865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Casetti T, Manes G, Chilovi F, Sprujevnik T, Bianco MA, Brancaccio ML, Imbesi V, Benvenuti S. Degree of concordance between double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Arakawa D, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Honda W, Shirai O, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Niwa Y, Maeda O, Ando T. Outcome after enteroscopy for patients with obscure GI bleeding: diagnostic comparison between double-balloon endoscopy and videocapsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:866-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zheng Y, Hawkins L, Wolff J, Goloubeva O, Goldberg E. Detection of lesions during capsule endoscopy: physician performance is disappointing. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:554-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Mergener K, Ponchon T, Gralnek I, Pennazio M, Gay G, Selby W, Seidman EG, Cellier C, Murray J, de Franchis R. Literature review and recommendations for clinical application of small-bowel capsule endoscopy, based on a panel discussion by international experts. Consensus statements for small-bowel capsule endoscopy, 2006/2007. Endoscopy. 2007;39:895-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

P- Reviewers Racz I, Swaminath A S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN