Published online Aug 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i8.347

Revised: February 27, 2012

Accepted: August 8, 2012

Published online: August 16, 2012

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a clinicopathological entity characterized by a set of symptoms similar to gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal epithelium. EoE is an emerging worldwide disease as documented in many countries. Recent reports indicate that EoE is increasingly diagnosed in both pediatric and adult patients although the epidemiology of this new disease entity remains unclear. It is unclear whether EoE is a new disease or a new classification of an old esophageal disorder. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and biopsies with histological examination of esophageal mucosa are required to establish the diagnosis of EoE, verify response to therapy, assess disease remission, document and dilate strictures and evaluate symptom recurrence of EoE. Repeated endoscopies with biopsies are necessary for monitoring of disease progression and treatment efficacy. EGD has a fundamental role in the diagnosis and management of EoE, forming an essential part of the investigation and follow-up of this condition. EoE is now considered a systemic disorder and not only a local condition with an important immunological background. One of the aims of research in EoE is to study non-invasive markers, such as immune indicators found in plasma, that correlate with local presence of EoE in esophageal tissues. Studies over the next few years will provide new information about diagnosis, pathogenesis, endoscopic/histologic criteria, non-invasive markers, novel and more efficacious treatments, as well as establishing natural history. Randomized clinical trials are urgently called for to inform non-invasive diagnostic tests, hallmarks of natural history and more efficacious treatment approaches for patients with EoE. The collaboration between pediatric and adult clinical and experimental studies will be paramount in the understanding and management of this disease.

- Citation: Ferreira CT, Goldani HA. Contribution of endoscopy in the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(8): 347-355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i8/347.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i8.347

Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders are increasingly described diseases that are characterized by eosinophilic infiltration and inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract in the absence of others identified causes of eosinophilia. These disorders include eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), eosinophilicgastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis[1].

EoE is a clinical entity characterized by a set of symptoms similar to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal epithelium[2]. EoE is an emerging worldwide disease as documented in many countries[3-9]. During the last decade, pediatric and adult specialists including gastroenterologists, allergists and pathologists have published a multidisciplinary body of literature solidifying the position of EoE as a distinct clinicopathological entity[10].

With the accumulating data providing evidence that EoE appears to be an antigen-driven immunologic process with multiple pathogenic pathways, a new conceptual definition is proposed to highlight that EoE represents a chronic, immune/antigen-mediated disease characterized clinically by symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction and histologically by eosinophil-inflammation[11].

The primary symptoms of EoE are also observed in patients with chronic esophagitis. However, in contrast to GERD, EoE is typically associated with normal pH probe results, occurs more frequently in males (75% to 80%), and appears to have a common familial incidence and a high rate of association with atopic diseases[1-3].

EoE affects all age groups but it was first described in children because routine biopsies are common practice in pediatric gastroenterology[12,13]. Recent reports indicate that EoE is increasingly diagnosed in both pediatric and adult patients although the epidemiology of this new disease entity remains unclear[14].

Epidemiological data indicate that EoE is now the second leading cause of chronic esophagitis, after GERD, and is a frequent cause of dysphagia[15]. A potential genetic component is suggested not only by the male predominance, but also by the increased number of white people affected and the augmented incidence in familial cases[16]. Familial clusters of EoE have been described, although the exact susceptibility loci for familial and sporadic disease require further clarification[17].

The prevalence of EoE seems to be rising, although increased detection is likely to have contributed to a change in prevalence statistics. According to a recent review the number of new patients has increased on an annual basis[16]. The authors suggested that although the background to this rise of EoE remains unclear, it is probably similar to the increase seen in other atopic diseases such as asthma and atopic dermatitis[16,18].

A recent electronic survey demonstrated that EoE is diagnosed more often in northeastern American states and urban areas than in rural settings[19]. Another recent systematic review of published literature stated the prevalence of EoE in adult populations varies considerably. It is high in dysphagia patients, quite low in population-based studies and intermediate among unselected endoscopy patients[7].

DeBrosse et al[20] have recently demonstrated a dramatic increase of incidence of new cases of esophageal eosinophilia over a 17-year period in their institution, but when corrected for the large increase in the number of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) performed, there was a stable proportion of esophageal eosinophilia per EGD. They suggest that EoE is not a new disease but instead is a new classification of a persistent esophageal disorder[20].

According to guidelines, EoE can only be diagnosed by endoscopy and biopsy with the finding of 15 or more eosinophils per high-power field (hpf) of esophageal tissue after aggressive treatment for gastroesophageal reflux medications[1,2]. An updated consensus report noted important additions since the 2007-consensus including a new potential disease phenotype, proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia, and genetic modifications that included EoE susceptibility caused by polymorphisms in the thymic stromal lymphopoietin protein gene[11].

Endoscopic findings coupled to histology have been used to support a diagnosis of EoE, and to assess response to therapy. Some patients may need endoscopic dilations in the case of eosinophilic strictures.

The treatment of EoE in the majority of children relies on elemental diets or elimination of one or several food allergens. In older children and adults, treatment usually involves a topical corticosteroid or short courses of systemic steroids. Monitoring of treatment response requires repeated esophagogastroscopic examinations and esophageal biopsies[1,2,11].

There have been few randomized controlled trials investigating optimal EoE management, and currently there is a paucity of reliable prognostic data regarding the long-term outcome of untreated patients. Among the different therapeutic approaches suggested for EoE none has absolute advantages[18,19]. Options should therefore be chosen on a patient-by-patient basis given their characteristics, their sensitivity to various allergens and treatment responses. This multidisciplinary approach to EoE is fundamental because of the frequent association of EoE and atopical manifestations. Coordination of the work of gastroenterologists and allergologists is essential, and it is also very important to involve nutritional experts in cases of significant food restriction.

The dramatic increase in prevalence of EoE over the last decade provides clinicians with new explanations for previously unexplained food impaction, dysphagia, heartburn, chest pain, vomiting and abdominal pain in children and in adults. Clinicians are faced with complex issues regarding the diagnosis and optimal management of these often difficult-to-treat patients. This review highlights some important aspects of EoE and special considerations in the contribution of endoscopy in the management of the condition.

According to the American Gastroenterological Association and the First International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Research Symposium (FIGERS), as recommended by the consensus report, EoE is a clinicopathological entity and its diagnosis is dependent on the demonstration of high eosinophilic counts in esophageal biopsies from a patient with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and the exclusion of GERD[1,2]. An increasing body of information describes a subset of patients whose symptoms and histological findings are responsive to proton pump-inhibitor (PPI) treatment and who might or might not have GERD[11]. The new guideline continues to define EoE as an isolated chronic disorder of the esophagus diagnosed by both clinical and pathological features but also describe a new disease phenotype, i.e., proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia[11].

The leading symptom of EoE in adolescents and adults is dysphagia for solids with the imminent risk of prolonged food impaction. Furthermore, patients frequently report retrosternal pain that is unrelated to swallowing activity. For this reason, esophageal biopsies should be taken to look for histological evidence of EoE in adult patients with unexplained dysphagia, even if results of endoscopy appear normal or identify other potential cause of dysphagia[11].

Clinical manifestations of EoE in infants and children are nonspecific and vary by age but are predominantly feeding difficulties[11]. The diagnostic guidelines regarding this disorder are evolving continuously as more is learned from ongoing research. However, diagnosis based on symptoms alone is not feasible. The clinical and histopathologic distinctions between EoE and GERD remain controversial and are based on limited data[20].

The number of eosinophils used to define EoE has varied widely in different publications and there are limited numbers of studies comparing patients with EoE and GERD[21]. Recent data report a substantial number of patients (30%) previously diagnosed with reflux esophagitis between 1982 and 1999 with histological evidence of EoE[20]. These patients were predominantly male and distinguished from patients with chronic esophagitis by a chief complaint of dysphagia[20]. Another important feature in the diagnosis is the absence of eosinophilia in others parts of gastrointestinal with mainly normal gastric and duodenal biopsies.

The diagnostic criteria have varied considerably not only in terms of eosinophil counts (5 to 30 eosinophils/hpf) but also in the definition of hpf, and the method of counting eosinophils[22].

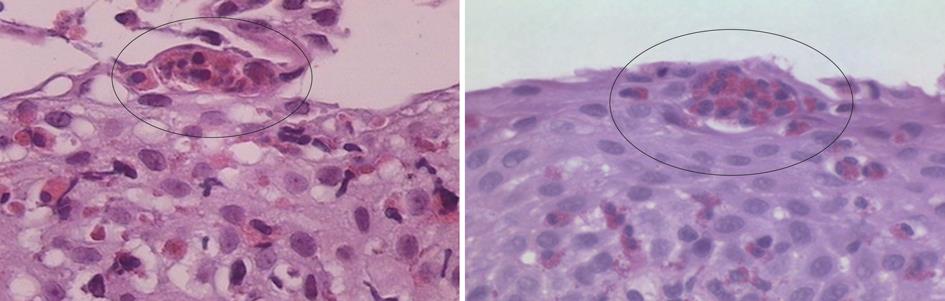

Intraepithelial eosinophilia is considered the cardinal histopathological feature, although it is not limited to EoE, and may be seen in a variety of other conditions including GERD, drug-related esophagitis, infections, Crohn’s disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis[22]. Other characteristics including eosinophilic micro abscesses and involvement of the long esophageal segment, albeit in a patchy distribution, have been observed to be associated with EoE[22] (Figure 1). Reactive mucosal changes such as basal cell hyperplasia and papillary elongation are other important features that can also be associated with GERD but may be more pronounced in EoE[21,22]. Aceves et al[23] have found pan-esophageal eosinophilia associated with pan-esophageal basal zone hyperplasia. They showed in children that biopsy specimens with less than 5 eosinophils per hpf never demonstrated basal zone hyperplasia. Studies have documented submucosal fibrosis and subepithelial sclerosis as important features of EoE[22,24,25].

Recently Lee et al[22], comparing 23 cases of EoE compared to 20 cases of GERD in an adult cohort, found that EoE patients had significantly higher eosinophils counts in proximal (39.4 vs 0.6 eosinophils/hpf) and distal biopsies (35.6 eosinophils/hpf vs 1.9 eosinophils/hpf) with high eosinophils counts (> 15/hpf) in proximal biopsies being an exclusive feature of EoE (83% vs 0%).

It is recognized that EoE tends to involve the esophagus more proximally than GERD[22,26]. Another major EoE diagnostic finding in that study was subepithelial sclerosis[22]. While intense eosinophilic infiltration most probably represents EoE, the diagnostic dilemma lies in those patients with biopsies that show intermediate numbers of eosinophils (5-15/hpf). In these cases additional pathological diagnostic features are necessary[27].

The diagnosis of EoE remains the responsibility of the gastrointestinal endoscopist and the pathologist because confirmatory endoscopic biopsies from esophageal mucosa are still the only means of establishing the diagnosis and assessing the effectiveness of treatment. Because the range of eosinophil numbers in EoE and GERD varies considerably, the potential exists for esophagitis with more than 15 eosinophils/hpf in the esophageal mucosa to respond completely to antireflux therapy[11,22,27-29]. In that setting, the clinical diagnosis could therefore be ‘‘GERD with reflux esophagitis,’’ despite the histological diagnosis of EoE, or according to the new guidelines it could be the phenotype “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia”. The number of eosinophils in reflux esophagitis is typically fewer than 7/hpf[27]. However, recent reports of children and adults who have large numbers of eosinophils consistent with EoE that responded to antireflux therapy lead us to be careful in assigning a clinical diagnosis[28,29]. This should be done only when additional information supports the diagnosis. Without clinical and pathologic follow-up EoE might well be overestimated[29]. Until more is known regarding this subgroup of patients, they should be given diagnoses of PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia[11]. Clinical judgment, as well as information derived from therapeutic response to PPI, impedance-pH monitoring, or both, should be taken into consideration to differentiate carefully between GERD-esophagitis and EoE[11].

PPI responsiveness or diagnostic testing (pH monitoring) might not adequately distinguish between GERD and EoE[11]. Future studies could help to determine whether PPIs may have a potential anti-inflammatory property or a barrier-healing role that helps to decrease an immune-antigen-driven response[11].

EGD and biopsies with histological examination of esophageal mucosa are required to establish the diagnosis of EoE, verify response to therapy, assess disease remission, document and dilate strictures and evaluate symptom recurrence of EoE. EGD is an essential part of the investigation and follow-up of EoE[1].

In contrast to the variable history and characteristic histology, endoscopic abnormalities can be very suggestive of EoE, but can often be unremarkable or misleading[19,21]. EoE presents a variety of signs, evoking an endoscopic pattern that is neither disease specific nor consistent in a range of examinations[30]. In general, findings of endoscopic mucosal abnormalities are used to support or refute a diagnosis of EoE and they are very important in assessing the response to treatment[31].

Repeated EGDs are often required to assess the efficacy of any therapeutic intervention for EoE. In addition, endoscopy potentially allows dilatation of esophageal strictures.

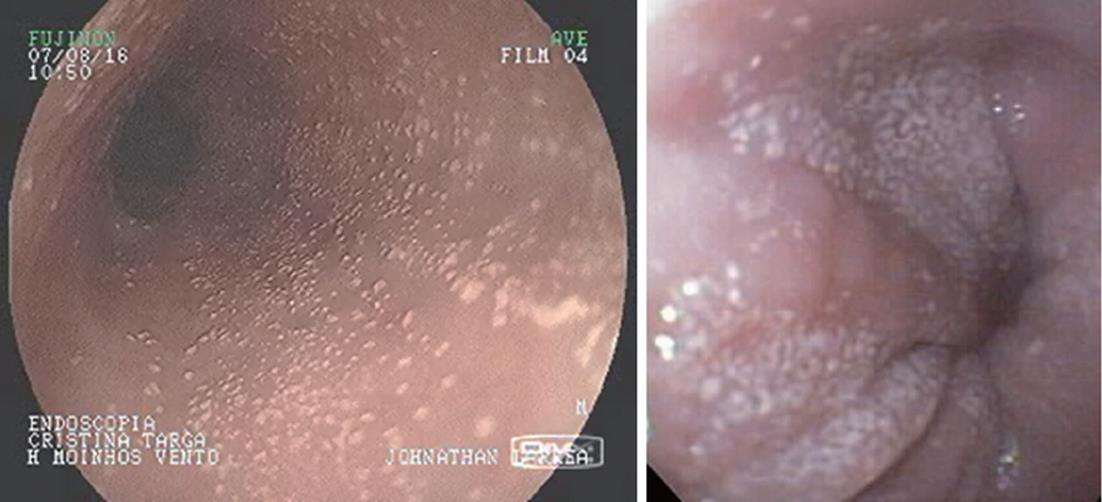

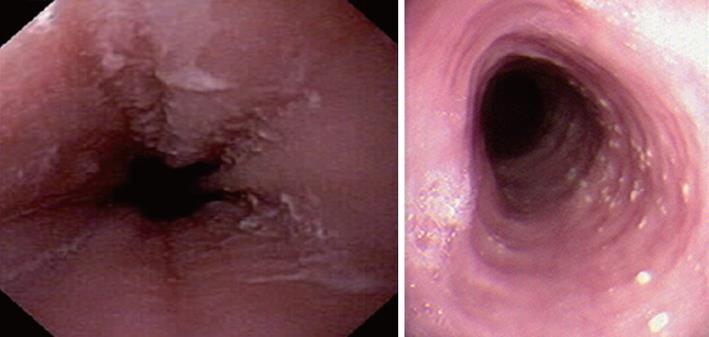

Characteristic upper endoscopic features in EoE include mucosal friability, erythema and loss of vascularity, linear furrowing, white plaques or exudates, concentric rings (esophageal “trachealization”), delicate mucosa (crepe-paper mucosa) prone to tearing and diffuse luminal narrowing or strictures. Another important finding of EoE is eosinophilic infiltrates in endoscopically normal esophagus. Significant intraepithelial eosinophilia can be found in about one third of patients with grossly unremarkable mucosa[3,32].

White mucosal plaques are a common feature, reflecting fibrinous exudates due to epithelial eosinophilic inflammation (Figure 2). Although the exact etiology is not known, the plaques are thought to represent eosinophilic abscesses on the surface of the esophageal mucosa. They may be mistaken for esophageal candidiasis and esophageal biopsies (culture) are, therefore, necessary to differentiate these disorders. While not pathognomonic, rings, linear furrows, or white plaques on endoscopy are very suggestive of EoE (Figure 3). The presence or absence of these endoscopic findings is used by most gastroenterologists, in making a diagnosis of EoE, to guide biopsy decisions, and to assess a patient’s response to therapy. It is still unclear whether endoscopists can reliably and accurately identify these findings. While the exact cause of the furrowing and ring-like formation is unknown, they are thought to represent tissue edema, inflammation and possible fibrosis. Chronic inflammation is of concern as it may cause progressive scarring, strictures, and potentially result in permanent narrowing of the esophagus[29,32]. Liacouras et al[3] reported retrospectively on a total of 381 pediatric patients (66% male, age 9.1 ± 3.1 years) who were diagnosed with EoE; 312 presented with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux and 69 with dysphagia. Endoscopically, 68% of patients had a visually abnormal esophagus: 41% had vertical lines, 12% had concentric rings, and 15% had white specks. Among those patients, 32% had a normal-appearing esophagus despite severe histological esophageal eosinophilia. The average numbers of esophageal eosinophils (per 400 × hpf) proximally and distally were 23.3 ± 10.5 and 38.7 ± 13.3, respectively[3].

In a retrospective study of 29 patients from southern Brazil with a median age of 7 years (76% male) we have found 24% with a normal-appearing esophagus, 48% with vertical furrowing, 41% with white mucosal plaques, and only 7% with concentric rings[6]. Several patients presented more than one feature as white specks and linear furrowing (Figures 4 and 5).

The FIGERS consensus guideline recommend taking several biopsies from different levels along the length of the esophagus, regardless of its macroscopic appearance[1]. Lower esophageal eosinophilia is common in GERD, and further counting of eosinophils in the proximalmucosa is needed to differentiate between GERD and EoE.

The patchy eosinophilic infiltration in proximal and distal esophageal mucosa is very important in the differential diagnosis with GERD. Therefore biopsies should be taken from several esophageal levels. Biopsies from stomach and duodenum should also be obtained to allow differentiation between EoE and a more widespread eosinophilic gastroenteritis[1,2]. It is noteworthy that a normal esophageal appearance does not rule out EoE[1-3].

A remaining unresolved question is which endoscopic signs reflect acute inflammation, and are therefore potentially reversible, and which signs persist despite successful treatment of the inflammation and are thus a possible manifestation of esophageal remodeling[15]. EoE may also be ascertained incidentally in patients undergoing endoscopy for other reasons.

One recent study was conducted to assess inter- and intraobserver reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light endoscopy and further adding narrow band imaging (NBI)[21]. Gastroenterologists identified rings and furrows with fair to good reliability, but did not reliably identify plaques or normal images. Intraobserver agreement varied and NBI did not improve endoscopic recognition. The conclusion was that endoscopic findings might not be reliable for supporting a diagnosis of EoE or for making treatment decisions[21]. Another report assessing the value of confocal laser endomicroscopy with video for the in vivo diagnosis of EoE has indicated the potential of this technique for the diagnosis of this new entity[33].

In terms of histology, the counting of eosinophils can be problematic because they often lie just under the luminal surface of the esophagus in EoE, and their number may be underestimated from a poorly oriented section in which the immediate subluminal area is outside the sample. The eosinophilia in EoE can be remarkably patchy, particularly during treatment. It is not unusual to have an abnormal biopsy specimen taken millimeters from another specimen that is completely normal.

Studies in adults with EoE have established that six biopsies taken from the esophagus are enough for diagnosis. Fewer biopsies can miss the diagnosis because of sampling errors[25,34]. By using 15 eosinophils/hpf as a threshold for diagnosis, one study identified that the sensitivity of a single biopsy was 73% and increased to 84%, 97% and 100% when taking 2, 3 and 6 biopsies, respectively[35]. According to the latest guidelines, 2 to 4 mucosal biopsies specimens of the proximal and distal esophageal mucosa should be obtained[11]. Long-standing disease tends to create a ringed appearance, more common in the adult population with EoE. In addition, strictures, diffuse narrowing (so-called ‘‘small-caliber esophagus’’), and friability of the epithelium, such that it longitudinally tears with passage of the scope (tissue paper mucosa), can be features of more long duration EoE.

Repeat endoscopy at appropriate intervals is needed to determine whether the inflammation has completely abated, irrespective of the therapy initiated. Symptoms can resolve in 2 to 4 wk, regardless of the type of treatment, but this is an unreliable measure of inflammation because the absence of symptoms does not assure the absence of inflammation. Histological response to topical steroids is generally complete in 4 to 12 wk. Histological response to dietary antigen elimination can be seen in 4 to 8 wk but is remarkably variable, having taken more than 4 mo in some individuals[27].

Evidence-based guidelines on the frequency of follow-up endoscopy have not been published, and frequency varies in clinical practice. In some practices the endoscopy is repeated 12 wk after diet or medication change, allowing sufficient time for a response to develop[27]. Incomplete responses are difficult to interpret and often require extension of the trial and repeated endoscopy to access the impact of therapy before changing the protocol[27]. Successful therapy results in complete resolution of the inflammation. When partial responses occur they must be evaluated for the necessity of more aggressive or alternative therapy, depending on the degree of remaining inflammation.

Chronic and active EoE is associated with tissue remodeling, manifest as deposition of dense collagen in the lamina propria. There is risk for the development of small-caliber esophagus and strictures, both of which have been observed as consequences of EoE in children and adults[30]. Assuring that esophageal histology has returned to normal seems to be an essential part of the management of each patient, to prevent further injury to the esophagus. Endoscopic re-evaluation after diet or medication changes determines whether a specific therapy has achieved a complete histological response and forms the basis for future management, with the goal of maintaining clinical and histological remission to avoid long-term complications such as esophageal stricture formation[27].

Some subjects with more severe disease present with severe structuring, furrowing, and ortrachealization, or food impaction which may need mechanical dilation of the esophagus. Endoscopic dilation should only be considered in cases with persistent symptoms and reduction in the caliber of the esophagus that have failed to respond to medical therapies. After instrumentation, tearing of the esophagus may occur in patients with moderate to severe inflammation. The mucosa may be extremely friable and may tear simply with the introduction of an endoscope during a routine diagnostic study because of the underlying edema and fibrosis. More significant tears have been reported in patients with small caliber esophagus or in patients undergoing esophageal dilatation.

EoE has been associated with an increased risk of esophageal mucosal tears induced by vomiting to dislodge impacted food. However, Boerhaave’s syndrome or transmural perforation of the organ resulting from vomiting induced to dislodge impacted food has rarely been reported[36]. This rare complication of EoE has been documented in 13 reports, predominantly affecting young men in whom EoE had not been previously diagnosed, despite the majority having esophageal symptoms and a history of atopy[36]. There are only two published cases of esophageal perforation in children, and these were managed conservatively. Esophageal perforation caused by vomiting is a potentially severe complication of EoE that is being increasingly described in literature. Therefore, patients with non-traumatic Boerhaave’s syndrome should be assessed for EoE, especially if they are young men who have a prior history of dysphagia and allergic manifestations[36].

The long-term consequences of esophageal eosinophilic infiltration, fibrous remodeling or possible modification using different therapies are controversial. For these reasons, it is difficult to recommend common guidelines for all patients although EoE should be considered a chronic disease with intermittent symptoms, persistent histological inflammation which affects patients quality-of-life[30]. Current guidelines suggest repeated biopsies for monitoring of disease progress and treatment efficacy. Since repeated endoscopy with biopsy entails risks to patients and costs to the medical system, the current aim is to study immune markers in plasma that correlate with a local presence in esophageal tissues in EoE subjects.

Because EoE and GERD cannot be differentiated on the basis of eosinophil counts alone, it can be a challenge to distinguish these disorders[21]. GERD and EoE need to be distinguished as they do not respond, in most of patients, to the same treatment[34]. Patients with EoE present with symptoms similar to those of GERD along with dense esophageal eosinophilia (with normal gastric and duodenal biopsies)[1,2]. Acid-induced esophagitis as a manifestation of GERD is the most frequent confounding diagnosis because reflux esophagitis may coexist with clinical EoE or mimic it histologically on hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections. Few mast cells are present in reflux esophagitis, which may help in discriminating it from EoE at presentation provided special stains are applied to identify them, as they are not distinguishable on hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections[37,38]. Some studies have identified increased numbers of mast cells in EoE patients in comparison to patients with GERD[39]. In the same way, EoE shows degranulating and active eosinophils in esophageal epithelium and molecular studies show specific up-regulated genes. Microarray analysis reveals signature panels which are distinct between patients with GERD and EoE[37,38].

Given to the coexistence of GERD in many cases of EoE and the effect shown by acid secretion inhibitors in controlling symptoms, in cases of suspected EoE, it is appropriate to carry out a therapeutic test using high dose PPIs over a period of 8 wk before repeating the endoscopy and taking further biopsies. This measure could correctly characterize those patients in whom EoE and GERD coexist and, in addition, would be better than monitoring the esophageal pH for ruling out GERD as the cause of eosinophilia[34,40]. It is only be possible to propose specific treatment for EoE when the persistence of the eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate and the symptoms deriving from it continue in spite of previous acid blockade[41].

In the latest guidelines the inclusion of the new phenotype “PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia” challenges these concepts because therapeutic and basic studies as well as clinical experience have identified a potential anti-inflammatory or barrier-healing role for proton pump inhibition in patients with esophageal eosinophilia[11]. Potential explanations include healing of a disrupted epithelial barrier to prevent further immune activation, decreased eosinophil longevity, inherent anti-inflammatory proprieties of PPIs, or unreliable diagnostic testing[11]. According to current guidelines, responsiveness to PPI therapy rules out EoE. However, this statement is being questioned, since recent reports have indicated in vitro anti-inflammatory effects of PPIs, independent of acid suppression[29]. Cortes et al[42] demonstrated that omeprazole improved murine asthma by down-regulating interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13 and signal transducer and activator of transcription factor 6. Zhang et al[43] have demonstrated that PPIs suppress IL-13-induced eotaxin-3 expression by the acid-independent mechanism.

Currently, neither histopathology nor distribution of inflammatory changes in esophageal biopsies predicts response to PPI treatment[11]. Eosinophilic microabscesses and superficial layering of eosinophils are more typical of findings associated with EoE than GERD[11].

Features of GERD can coexist with EoE. Because of this, separating the 2 disorders into distinct diseases may be very difficult. Several theories regarding this interaction have been proposed: GERD causes esophageal injury with subsequent development of esophageal eosinophilic infiltration; GERD and EoE coexist but are unrelated; because of esophageal inflammation, EoE causes or contributes to the development of secondary GERD (poor motility); GERD causes mucosal disruption contributing to the development of EoE[44].

The high frequency of GERD described in adult populations with EoE suggests that there may be more than a chance association between the two conditions[44]. A trial of PPIs, even when diagnosis of EoE is clear-cut, is recommended[44]. However, on some occasions PPI responsiveness as well as diagnostic testing might not be helpful in distinguish between GERD and EoE[11].

Dellon et al[45] performed the largest retrospective clinical, endoscopic, and histological case-control study on data collected from 2000 to 2007 to differentiate between GERD and EoE. Data from 151 patients with EoE and 226 with GERD were analyzed. Features that independently predicted EoE included younger age, symptoms of dysphagia, documented food allergies, observations of esophageal rings, linear furrows, white plaques, or exudates and an absence of a hiatal hernia by upper endoscopy. In biopsy specimens, a higher maximum eosinophil count and the presence of eosinophil degranulation were observed[45].

The identification of histological features of EoE in nearly 30% of patients previously given diagnoses of reflux esophagitis suggests that EoE might have been under-diagnosed in the 1980s and 1990s[20]. On the other hand, Molina-Infante et al[29] demonstrated 75% of unselected patients and 50% with an EoE phenotype responding to PPI therapy. They stated that patients with PPI-responsive eosinophilic infiltration are phenotypically indistinguishable from EoE patients, thereby overestimating EoE[29]. Dohil et al[46] have recently suggested that patients with PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia should have ongoing monitoring for EoE during PPI monotherapy because this is a transient phenomenon. A database search revealed children who had an initial histological response to PPI monotherapy but had recurrence of esophageal eosinophilia and symptoms despite continued PPI therapy.

Additional follow-up studies are needed to better delineate EoE and GERD. In the pediatric EoE population is important to define disease behavior and to assess whether pediatric and adult EoE represent a continuum.

The endoscopic data concerning EoE represent a distinctive pattern of nonerosive inflammatory disease that can involve superficial or deep esophageal layers and present with a variety of clinical symptoms. Early recognition of these findings and their variability may lead to improved care of patients who have EoE. Upper endoscopy with biopsies is essential for the diagnosis, and for assessing the follow up of these patients. It is therefore crucial for the endoscopist to become familiar with the clinical and endoscopic EoE findings to ensure correct diagnosis and treatment.

Emerging data has increased our knowledge of EoE but important questions remain unanswered. Over the last decade pediatric and adult clinicians have published a multidisciplinary body of information confirming EoE as a distinct clinicopathological entity. Significant diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic uncertainties are still associated with EoE, because it is a relatively recently discovered medical condition[11].

Basic science has in recent years unraveled some of the underlying pathological mechanisms of EoE, which lead to eosinophil recruitment, infiltration and activation as well as lesions in the esophagus. However, it is not yet clear which patient characteristics are associated with an increased risk of stricturing disease and whether lower degrees of symptoms or eosinophilic infiltration deserve treatment at all. Controversy remains as to whether histology and endoscopic findings should aim for complete mucosal remission, eosinophilic clearance or merely for symptomatic control, There are many remaining issues which cannot be resolved based on current published knowledge. These include the definition of EoE phenotypes allowing clear differentiation between EoE and GERD.

Subjects with EoE have different immune indicator profiles in blood plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and local esophageal tissue from subjects with GERD, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, and healthy controls. This suggests that EoE is not only a local condition but also a systemic disorder that may be detected through analysis of plasma samples[47]. These indicators could serve in the near future as surrogate non-invasive markers that could be a useful substitute for endoscopy and biopsies[47]. Some authors, for example, have recently demonstrated that fibroblast growth factors may play an important role in the pathophysiology of EoE and may be part of a set of immune indicators that could, without biopsy, differentiate EoE subjects from subjects with other clinically similar symptoms such as GERD[47].

Future studies will provide new information about diagnosis, pathogenesis, endoscopic /histological criteria, non-invasive markers and novel and more efficacious treatments, as well as establishing natural history. Randomized clinical trials are urgently needed to inform non-invasive diagnostic tests, hallmarks of natural history and more efficacious treatment approaches for patients with EoE[12]. The collaboration between pediatric and adult clinical and experimental studies will be paramount in the understanding and management of this disease.

| 1. | Liacouras CA, Bonis P, Putnam PE, Straumann A, Ruchelli E, Gupta SK, Lee JJ, Hogan SP, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME. Summary of the First International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Research Symposium. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:370-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1342-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1400] [Cited by in RCA: 1174] [Article Influence: 61.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liacouras CA, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Verma R, Mascarenhas M, Semeao E, Flick J, Kelly J, Brown-Whitehorn T, Mamula P. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 28.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cherian S, Smith NM, Forbes DA. Rapidly increasing prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in Western Australia. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:1000-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Beausoleil JL, Franciosi J, Shuker M, Verma R, Liacouras CA. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features and prognosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ferreira CT, Vieira MC, Vieira SM, Silva GS, Yamamoto DR, Silveira TR. [Eosinophilic esophagitis in 29 pediatric patients]. Arq Gastroenterol. 2008;45:141-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sealock RJ, Rendon G, El-Serag HB. Systematic review: the epidemiology of eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:712-719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prasad GA, Alexander JA, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Smyrk TC, Elias RM, Locke GR, Talley NJ. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis over three decades in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1055-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis: escalating epidemiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:418-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee JJ, Furuta GT. Upper gastrointestinal tract eosinophilic disorders: pathobiology and management. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2006;8:439-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3-20.e6; quiz 21-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1605] [Cited by in RCA: 1518] [Article Influence: 101.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Allen KJ, Heine RG. Eosinophilic esophagitis: trials and tribulations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:574-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fox VL, Nurko S, Furuta GT. Eosinophilic esophagitis: it's not just kid's stuff. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:260-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enns R, Kazemi P, Chung W, Lee M. Eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical features, endoscopic findings and response to treatment. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010;24:547-551. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Felder S, Kummer M, Engel H, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, Schoepfer A, Simon HU. Budesonide is effective in adolescent and adult patients with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1526-137, 1537.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Franciosi JP, Tam V, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. A case-control study of sociodemographic and geographic characteristics of 335 children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:415-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Collins MH, Blanchard C, Abonia JP, Kirby C, Akers R, Wang N, Putnam PE, Jameson SC, Assa'ad AH, Konikoff MR. Clinical, pathologic, and molecular characterization of familial eosinophilic esophagitis compared with sporadic cases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:621-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cianferoni A, Spergel JM. Food allergy: review, classification and diagnosis. Allergol Int. 2009;58:457-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Spergel JM, Book WM, Mays E, Song L, Shah SS, Talley NJ, Bonis PA. Variation in prevalence, diagnostic criteria, and initial management options for eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases in the United States. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:300-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | DeBrosse CW, Collins MH, Buckmeier Butz BK, Allen CL, King EC, Assa'ad AH, Abonia JP, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME, Franciosi JP. Identification, epidemiology, and chronicity of pediatric esophageal eosinophilia, 1982-1999. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:112-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dellon ES, Aderoju A, Woosley JT, Sandler RS, Shaheen NJ. Variability in diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2300-2313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee S, de Boer WB, Naran A, Leslie C, Raftopoulous S, Ee H, Kumarasinghe MP. More than just counting eosinophils: proximal oesophageal involvement and subepithelial sclerosis are major diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic oesophagitis. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:644-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, Schwimmer J, Bastian JF. Distinguishing eosinophilic esophagitis in pediatric patients: clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features of an emerging disorder. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:252-256. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Parfitt JR, Gregor JC, Suskin NG, Jawa HA, Driman DK. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults: distinguishing features from gastroesophageal reflux disease: a study of 41 patients. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:90-96. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chehade M, Sampson HA, Morotti RA, Magid MS. Esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:319-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gonsalves N, Policarpio-Nicolas M, Zhang Q, Rao MS, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability and endoscopic correlates in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:313-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Putnam PE. Evaluation of the child who has eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2009;29:1-10, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ngo P, Furuta GT, Antonioli DA, Fox VL. Eosinophils in the esophagus--peptic or allergic eosinophilic esophagitis Case series of three patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1666-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Ripoll C, Hernandez-Alonso M, Mateos JM, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Dueñas C, Fernandez-Gonzalez N, Quintana EM, Gonzalez-Nuñez MA. Esophageal eosinophilic infiltration responds to proton pump inhibition in most adults. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:110-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Straumann A. The natural history and complications of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2008;18:99-118; ix. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Peery AF, Cao H, Dominik R, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Variable reliability of endoscopic findings with white-light and narrow-band imaging for patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:475-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chang F, Anderson S. Clinical and pathological features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: a review. Pathology. 2008;40:3-8. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Neumann H, Vieth M, Atreya R, Mudter J, Neurath MF. First description of eosinophilic esophagitis using confocal laser endomicroscopy (with video). Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Genevay M, Rubbia-Brandt L, Rougemont AL. Do eosinophil numbers differentiate eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:815-825. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Shah A, Kagalwalla AF, Gonsalves N, Melin-Aldana H, Li BU, Hirano I. Histopathologic variability in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:716-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lucendo AJ, Friginal-Ruiz AB, Rodríguez B. Boerhaave's syndrome as the primary manifestation of adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Two case reports and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2011;24:E11-E15. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 37. | Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Jameson SC, Kirby C, Konikoff MR, Collins MH. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:536-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Furuta GT, Straumann A. Review article: the pathogenesis and management of eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lucendo AJ, Bellón T, Lucendo B. The role of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2009;20:512-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Molina-Infante J, Ferrando-Lamana L, Fernandez-Bermejo M, Porcel-Carreño S. Eosinophilic esophagitis in GERD patients: a clinicopathological diagnosis using proton pump inhibitors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2856-2857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | González-Castillo S, Arias A, Lucendo AJ. Treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: how should we manage the disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:663-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cortes JR, Rivas MD, Molina-Infante J, Gonzalez-Nuñez MA, Perez-G M, Masa JF, Sanchez JF, Zamorano J. Omeprazole inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 activation and reduces lung inflammation in murine asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:607-10, 610.e1. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Zhang X, Cheng E, Huo X, Yu C, Hormi-Carver KK, Andersen J, Spechler SJ, Souza RF. In esophageal squamous epithelial cell lines from patients with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), omeprazole blocks the stimulated secretion of eotaxin-3: a potential anti-inflammatory effect of omeprazole in eoe that is independent of acid inhibition. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S-122. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 44. | Spechler SJ, Genta RM, Souza RF. Thoughts on the complex relationship between gastroesophageal reflux disease and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1301-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Dellon ES, Gibbs WB, Fritchie KJ, Rubinas TC, Wilson LA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. Clinical, endoscopic, and histologic findings distinguish eosinophilic esophagitis from gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1305-1313; quiz 1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Dohil R, Newbury RO, Aceves S. Transient PPI responsive esophageal eosinophilia may be a clinical sub-phenotype of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:1413-1419. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Huang JJ, Joh JW, Fuentebella J, Patel A, Nguyen T, Seki S, Hoyte L, Reshamwala N, Nguyen C, Quiros A. Eotaxin and FGF enhance signaling through an extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK)-dependent pathway in the pathogenesis of Eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2010;6:25. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Kaushal Kishor Prasad, Associate Professor, Chief, MD, PDCC, Division of GE Histopathology, Department of Superspeciality for Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Sector-12, Chandigarh 160012, India; Luis Rodrigo, Professor, Gastroenterology Service, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, c/ Celestino Villamil s. nº, Oviedo 33-006, Spain; Hoon Jai Chun, Professor, Korea University College of Medicine,126-1, 5-ga Anam-dong, Seongbuk-gu, Seoul 136-705, South Korea

S- Editor Song XX L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Zheng XM