Published online Mar 16, 2012. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v4.i3.50

Revised: November 4, 2011

Accepted: March 1, 2012

Published online: March 16, 2012

Vasculitis is an inflammation of vessel walls, followed by alteration of the blood flow and damage to the dependent organ. Vasculitis can cause local or diffuse pathologic changes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The variety of GI lesions includes ulcer, submucosal edema, hemorrhage, paralytic ileus, mesenteric ischemia, bowel obstruction, and life-threatening perforation.The endoscopic and radiographic features of GI involvement in vasculitisare reviewed with the emphasis on small-vessel vasculitis by presenting our typical cases, including Churg-Strauss syndrome, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Behçet’s disease. Important endoscopic features are ischemic enterocolitis and ulcer. Characteristic computed tomographic findings include bowel wall thickening with the target sign and engorgement of mesenteric vessels with comb sign. Knowledge of endoscopic and radiographic GI manifestations can help make an early diagnosis and establish treatment strategy.

- Citation: Hokama A, Kishimoto K, Ihama Y, Kobashigawa C, Nakamoto M, Hirata T, Kinjo N, Higa F, Tateyama M, Kinjo F, Iseki K, Kato S, Fujita J. Endoscopic and radiographic features of gastrointestinal involvement in vasculitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4(3): 50-56

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v4/i3/50.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v4.i3.50

Vasculitis is an inflammation of vessel walls, followed by alteration of the blood flow and damage to the dependent organ. It can affect vessels of all sizes. The clinical course and pathological features are quite variable and dependon the size and location of the affected vessels[1,2]. Vasculitis can cause local or diffuse pathologic changes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The variety of GI lesions includes ulcer, submucosal edema, hemorrhage, paralytic ileus, mesenteric ischemia, bowel obstruction, and perforation[3]. Of note, bowel ischemia and perforations are significantly associated with increased mortality[4]. Knowledge of endoscopic and radiographic GI manifestations can suggest the possibility of systemic vasculitis and help establish the specific diagnosis[5-7]. Although radiographic features of vasculitis involving the GI tract have been well studied especially in computed tomography (CT), the combination of endoscopic and radiographic features has not been fully evaluated. We herein review the endoscopic and radiographic features of GI involvement in vasculitiswith the presentation of our typical cases.

Vasculitis is classified as primary or secondary (Table 1). Primary vasculitis was defined by the Chapel Hill International Consensus on the Nomenclature of Systemic Vasculitis[1]. The conference classified ten vasculitides into large-vessel vasculitis, medium-sized-vessel vasculitis, and small-vessel vasculitis, depending on the types of predominantly affected vessels. Large-vessel vasculitis affects the aorta and the largest arterial branches,and includesgiant-cell (temporal) arteritis and Takayasu’s arteritis. Medium-sized-vessel vasculitis affects the main visceral arteries and their branches, and includespolyarteritisnodosa and Kawasaki’s disease. Small-vessel vasculitis affects arterioles, venules, and capillaries, and includes Wegener’s granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, microscopic polyangiitis, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, and cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis[1].Secondary vasculitis is caused by connective tissue diseases (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus, Behçet’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis), bacterial and viral infection, malignancy, and drugs. Most cases of secondary vasculitis present with small-vessel vasculitis[2,5].

| Primary vasculitis |

| Large-vessel vasculitis |

| Giant-cell (temporal) arteritis |

| Takayasu's arteritis |

| Medium-sized-vessel vasculitis |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Kawasaki's disease |

| Small-vessel vasculitis |

| Wegener's granulomatosis |

| Churg-strauss syndrome |

| Microscopic polyangitis |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura |

| Essential cryoglobulinemic vasculitis |

| Cutaneous leukocytoclastic vasculitis |

| Secondary vasculitis |

| Connective tissue diseases |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Behçet's disease |

| Rheumatoid arthritis |

| Infectious diseases |

| Bacteria |

| Virus |

| Drugs |

| Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Anti-cancer drugs |

| Antibiotics |

| Paraneoplastic vasculitis |

| Carcinoma |

| Lymphoproliferative neoplasm |

| Myeloproliferative neoplasm |

Giant cell (temporal) arteritis: Giant cell (temporal) arteritis is a form of granulomatous arteritis of the aorta and its major branches, with a predilection for the extracranial branches of the carotid artery[1]. It is often associated with polymyalgia rheumatica. The frequency of its GI involvement is rare[5,8].

Takayasu’s arteritis: Takayasu’s arteritis (TA) is a form of granulomatous inflammation of the aorta and its major branches[1].It is characterized by ocular disturbances and decreased brachial artery pulse (pulseless disease). The descending aortic syndrome may cause mesenteric vasculitis, but the frequency of mesenteric or celiac involvement is rare[3,5,6,8]. Although the precise etiology is unknown, the coexistence of TA and ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease has been increasingly reported[9,10].

Polyarteritis nodosa: Polyarteritis nodosa (PN) is a form of necrotizing inflammation of medium-sized or small arteries without glomerulonephritis or vasculitis in arterioles, capillaries, or venules[1]. Approximately two-thirds of the patientshave abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or other manifestations associated with GI ischemia and infarction[3,5-7]. The clinical course is often dramatic. The typical radiographic feature is an angiographic finding of aneurysms up to 1 cm in diameter within the renal, mesenteric, and hepatic vasculature[3].

Kawasaki’s disease: Kawasaki’s disease is a form of arteritis involving large, medium-sized, and small arteries and is associated with mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome[1]. It usually occurs in children and coronary arteries are often involved. GI involvement is relatively uncommon but acute abdomen with paralytic ileus, ischemic enteritis, and vasculitic appendicitis may occur[6].

Wegener’s granulomatosis: Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) is a form of granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis affecting small-to-medium-sized vessels[1]. GI involvement is relatively rare and granulomatous colitis or gastritis may occur[5].

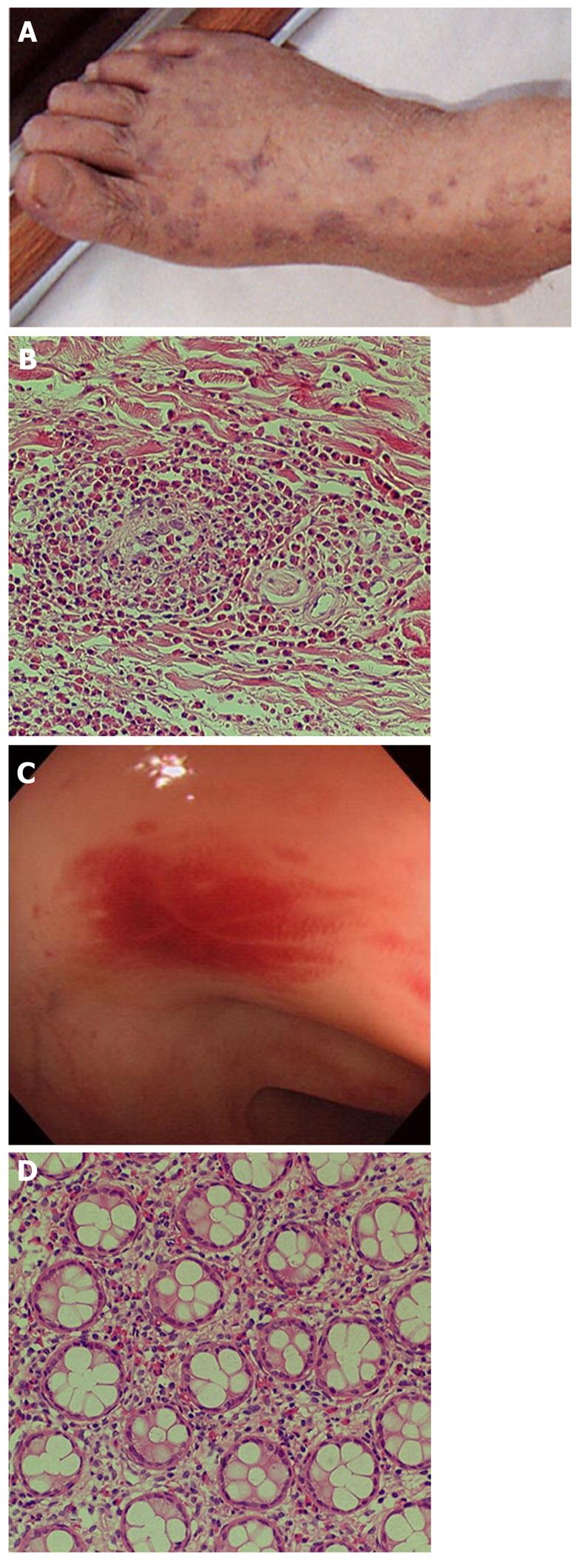

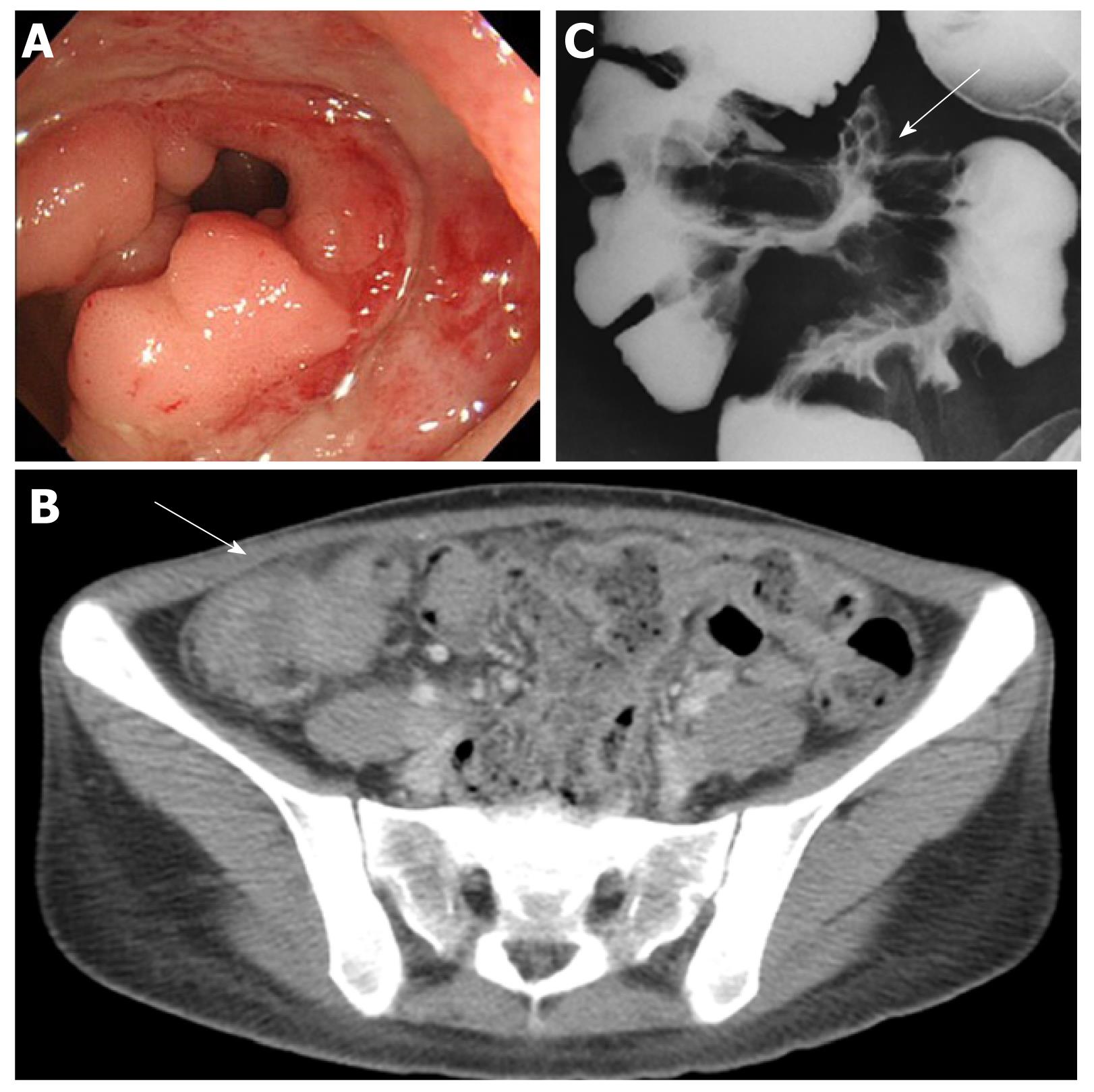

Churg-Strauss syndrome: Churg-Strauss syndrome(CSS) is a form of eosinophil-rich and granulomatous inflammation involving the respiratory tract and necrotizing vasculitis affecting small-to-medium-sized vessels and is associated with asthma and eosinophilia[1]. GI symptoms of CSS are abdominal pain and diarrhea caused by eosinophilic gastroenteritis (Figure 1)[11].Mesenteric vasculitis may occur, leading to GI ulceration, ischemia, and perforation. Among antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies-associated vasculitiswhich include WG, CSS, and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), GI involvement increases the risk of relapse in CSS[12].

Microscopic polyangiitis: MPA is a form of necrotizing vasculitis with few or no immune deposits affecting small vessels[1]. Although necrotizing glomerulonephritis and pulmonary capillaritis are very common, GI involvement is rare[6].

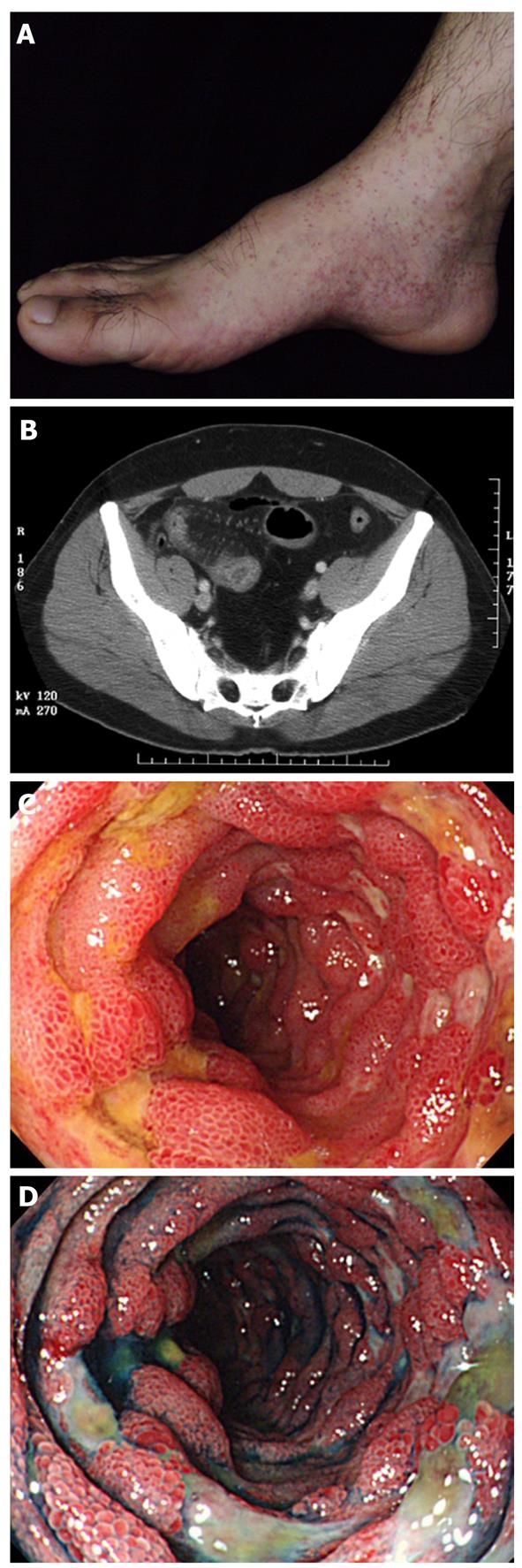

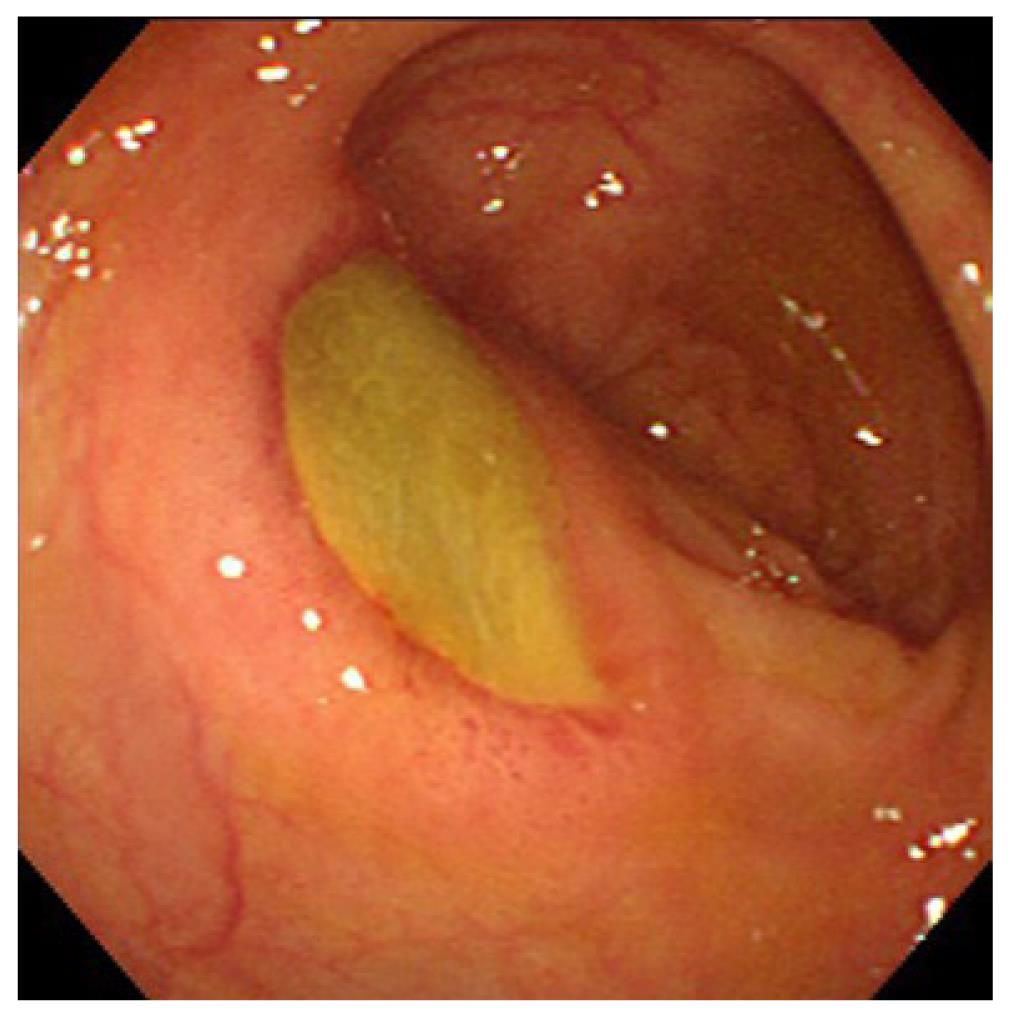

Henoch-Schönlein purpura: Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a form of vasculitis with IgA-dominant immune deposits affecting small vessels[1]. Although HSP is typically a disease of children, adult cases present more severe disease compared to children. It involves the skin, joints, GI tract and kidneys. GI symptoms include colicky abdominal pain and bleeding caused by bowel ischemia and edema. Serious complications include intussusception, infarction, and perforation[6,13]. The descending duodenum and the terminal ileum are frequently involved, with endoscopic characteristics of diffuse mucosal redness, petechiae, hemorrhagic erosions and ulcers[14].Longitudinal ulcers may be clear evidence of mesenteric vascular involvement (Figure 2)[15]. The CT features are bowel wall thickening with the target sign and engorgement of mesenteric vessels with comb sign (Figure 2)[15].

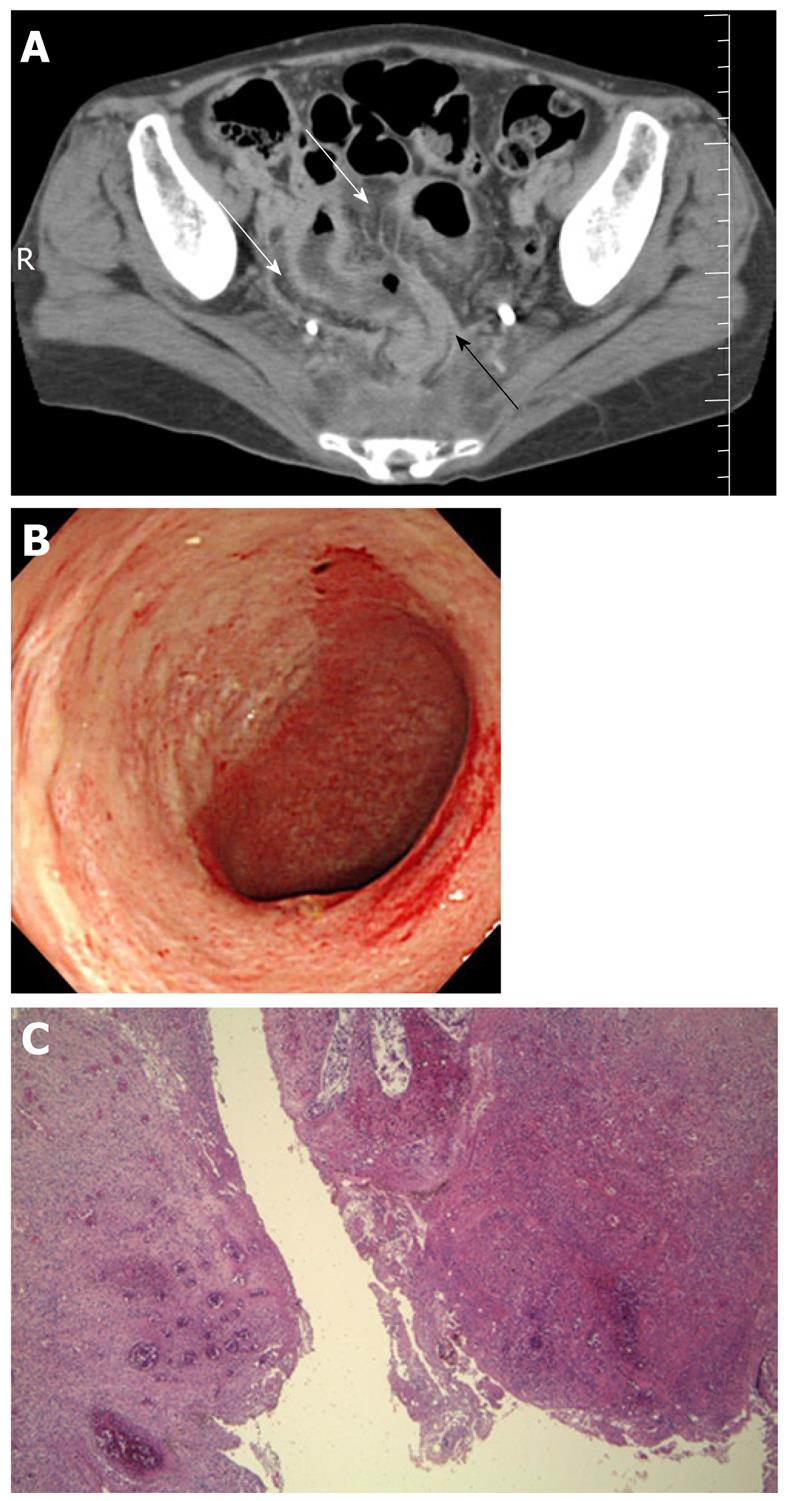

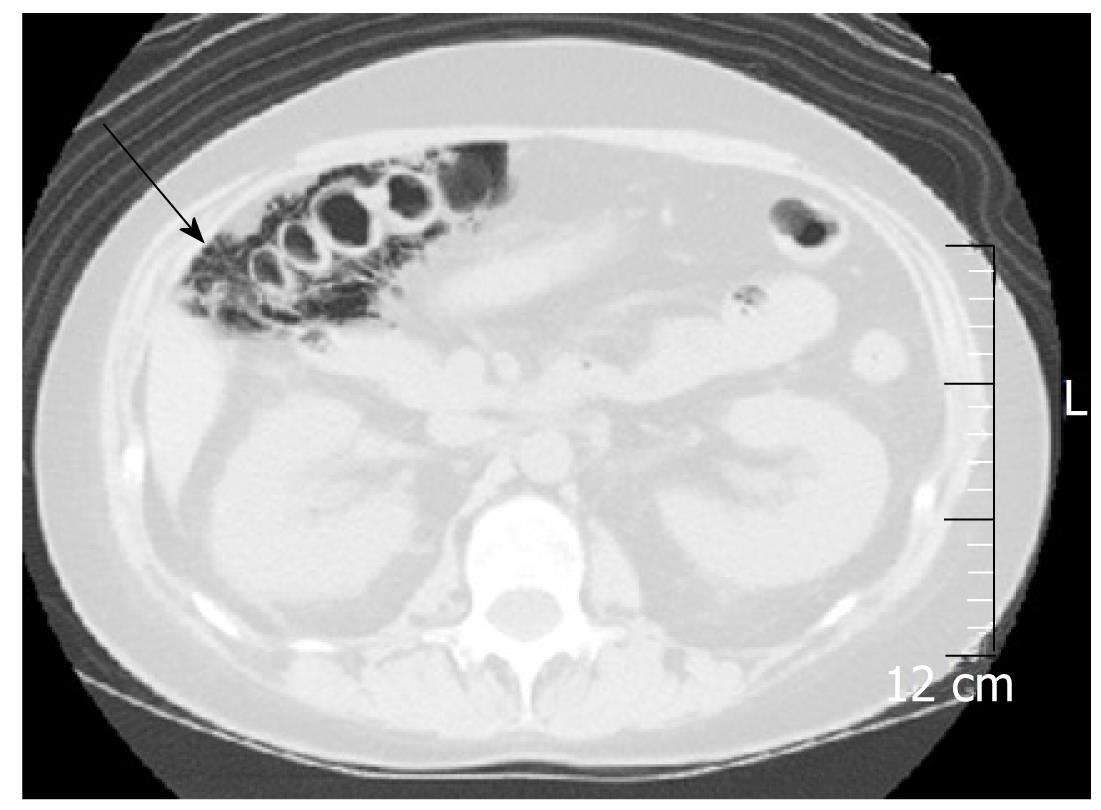

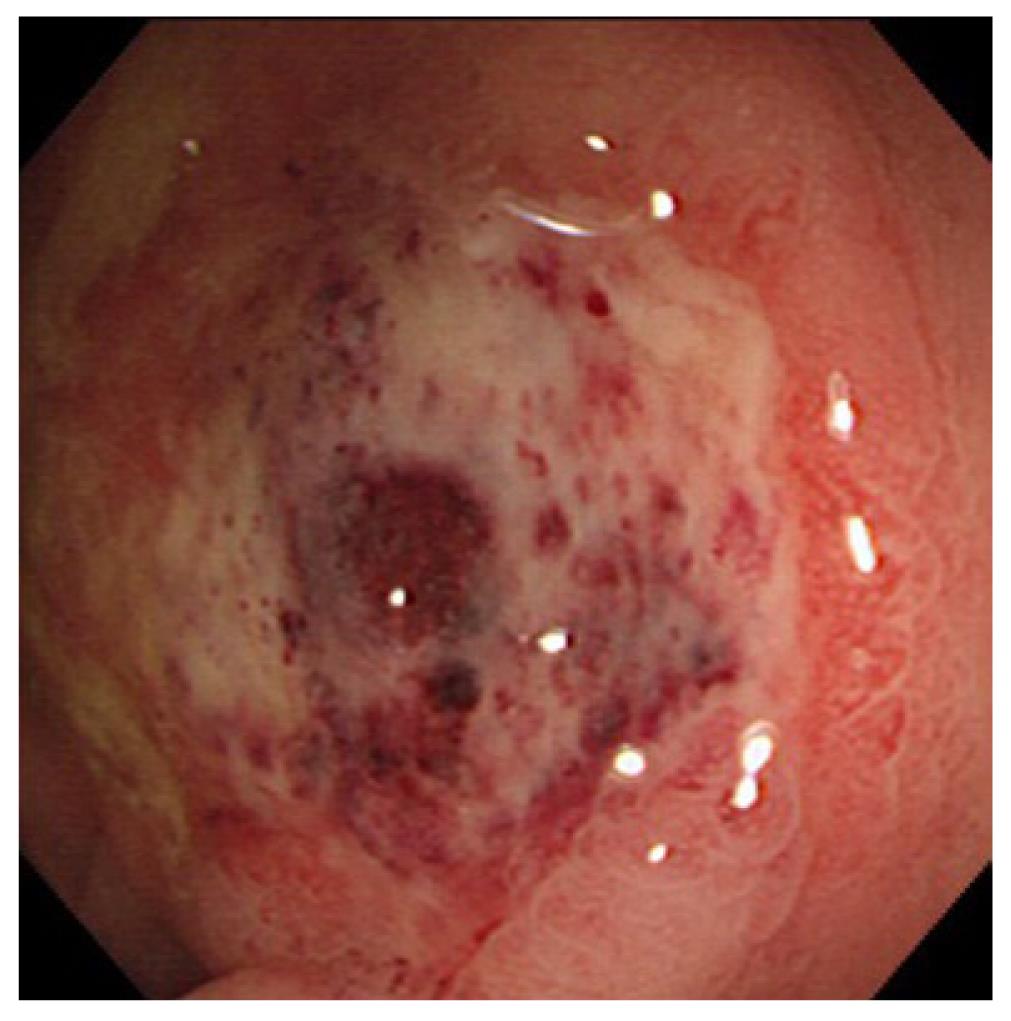

Systemic lupus erythematosus: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune connective tissue disease with local deposition of antigen-antibody complexes or antibodies inducing necrotizing vasculitis[3].It involves the skin, joints, GI tract, kidneys, central nervous system, and blood cells. Itfrequently involves any part of the GI tract, liver, and pancreas[16,17]. Acute abdominal pain caused by bowel ischemia secondary to lupus mesenteric vasculitis (LMV) is common[18]. The ischemic change can differ according to the sensitivity of the vessels in four different bowel layers; mucosal ulceration and hemorrhage, submucosal edema and intestinal pseudo-obstructiondue to muscular damage, and ascites and perforation due toserosal damage[18]. The endoscopic features areischemic enterocolitis and ‘punched out’ ulcers (Figure 3). Although histopathological diagnosis of LMV can be obtained[19], most endoscopic superficial biopsies might not yield a definitive diagnosis because the affected vessels are usually located in an inaccessible area[18]. The CT features include focal or diffuse bowel wall thickening with the target sign, bowel dilatation, ascites, and engorgement of mesenteric vessels with comb sign (Figure 3)[3,17]. LMV rarely causes pneumatosis intestinalis (PI)[20], which is gas collection in the bowel wall (Figure 4). PI may result in hepatic portal venous gas with a high mortality rate. Another important GI manifestation in SLE is protein losing gastroenteropathy[16]. Edematous villi and lymphangiectasia, which may be caused by immunological vascular or mucosal damage, have been the postulated pathology[20].

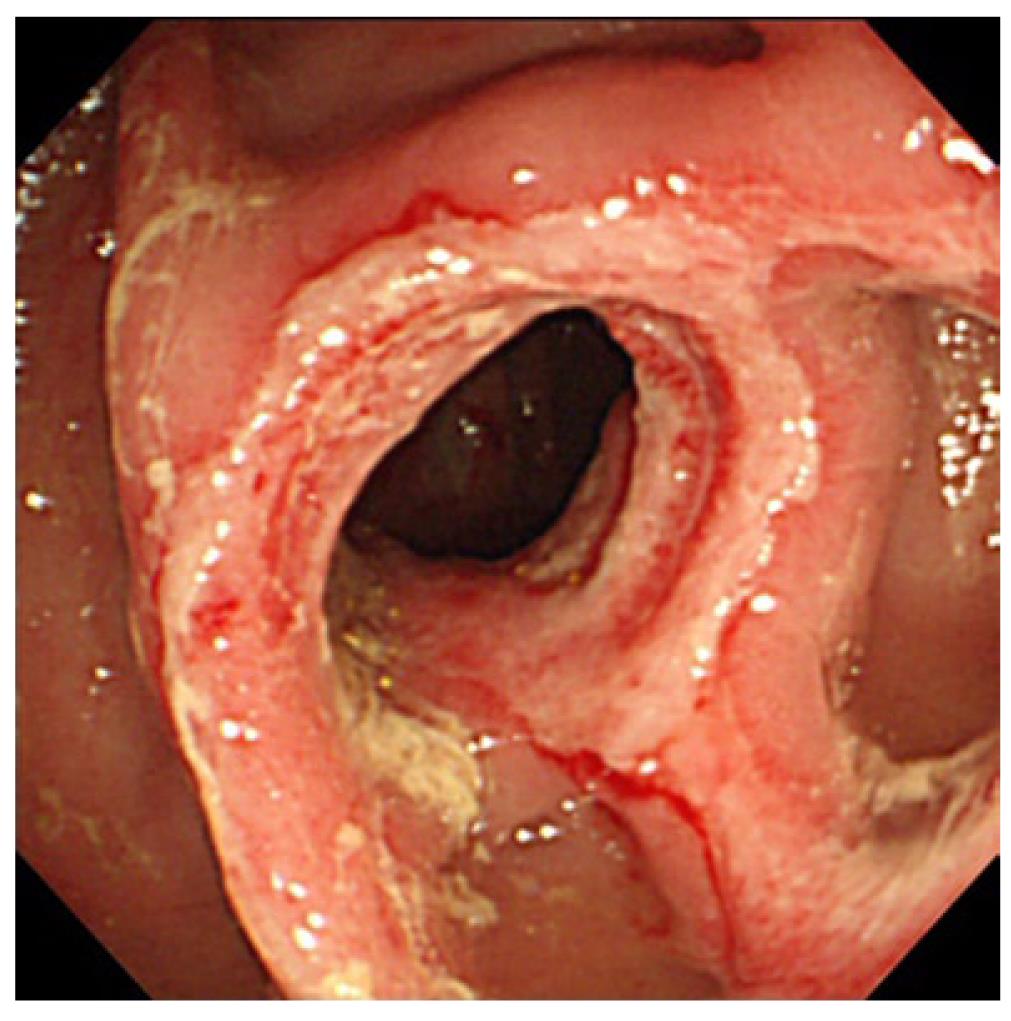

Behçet’s disease: Behçet’s disease (BD) is a nonspecific necrotizing vasculitis characterized by recurrent orogenital ulcers, uveitis, arthritis, and skinlesions[21,22]. It frequently involves nerves and the GI tract. The frequently involved sites are the ileocecal region and esophagus. The hallmark of BD is the presence of ulceration. Two types of ulceration occur: localized and diffuse[22]. In the ileocecal region, a localized large deeply penetrating ulcer may present with a high frequency of hemorrhage and perforation. The CT features are mass-like lesions and unevenly thickened bowel wall with marked enhancement[3,22]. Barium examination shows a large irregular ulcer with marked thickening of the surrounding intestinal wall (Figure 5). Diffuse lesions are small, multiple, discrete, “punched-out” ulcers commonly observed in the colon (Figure 6)[23]. A recent large scale study confirmed that patients with intestinal BD younger than 25 years, who had a history of prior laparotomy or volcano-shaped intestinal ulcers (the former type) have an increased risk of free bowel perforation[24].

Other small-vessel vasculitis: Drugs in nearly all pharmacological classes can cause drug-induced vasculitis/drug-induced lupus-like syndrome[25]. As the clinical presentation and pathological features are indistinguishable from primary vasculitis, a high index of suspicion is required for the accurate diagnosis of drug-induced vasculitis. Discontinuation of the suspected drugis often enough to induce prompt improvement, obviating immunosuppressive treatment.

Infectious agents often cause vasculitis via mechanisms including direct microbial invasion of vascular endothelial cells, immune complex-mediated damage and stimulation of autoreactive lymphocytes through molecular mimicry and superantigens[26]. Causative pathogens include bacteria (e.g., streptococci, mycobacteria, Treponema pallidum), viruses (e.g., cytomegalovirus, herpes virus, hepatitis virus B and C, human immunodeficiency virus), fungi, and parasites.

Vasculitis/connective tissue disease and malignancy are related and this association is bidirectional. Malignancy occurs more frequently in the course of vasculitis and vasculitis occurs in the course of malignancy[27,28]. Therefore, the presence of vasculitis/connective tissue disease may justify a workup for hidden malignancy. In addition, as blood hypercoagulability frequently occurs in malignancy, leading to thrombophlebitis and thrombosis[29], we should pay greater attention to vascular diseases in the treatment of cancer patients.

As immunosuppressive drugs, including prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, cyclosporine A, tacrolimus, and anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies, have been the key treatment for vasculitis, opportunistic infection can be a life-threatening complication. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) has been increasingly recognized as an important pathogen in such immunocompromised states[30]. GI symptoms of CMV infection are usually nonspecific and include abdominal pain, diarrhea and GI bleeding, which are similar to those of vasculitis. The colon and stomach are the most common sites of CMV GI infection. Endoscopic features are quite variable and include macroscopically normal mucosa, diffuse erythema[31], nodules, pseudotumors, erosions and ulcers[32], which are also similar to those of vasculitis. CMV-associated colonic ulcerin SLE is shown in Figure 7. Pathological proof of classical intranuclear inclusions is not always possible because CMV may infect vascular endothelium or connective tissue stromal cells under the ulcers. Therefore, several diagnostic methods should be used including CMV antigenemia assay and polymerase chain reaction of the specimen. Most GI CMV infections respond well to ganciclovir.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) are widely used in long-standing vasculitis/connective tissue diseases. Although gastroduodenal peptic ulceris well-known as a classic NSAID-induced GI damage, diaphragm disease (Figure 8)[33] and various types of enteropathy in the small and large intestine have received greater recognition as adverse effects of NSAIDs. Diagnosis is traditionally made by symptom improvement on discontinuation of the NSAID[34].

Any type of vasculitis can involve the GI tract. Bowel ischemia due to mesenteric vasculitis is frequently seen in association with increased mortality. Important endoscopic features areischemic enterocolitis and ulcer. Characteristic CT features include bowel wall thickening with the target sign and engorgement of mesenteric vessels with comb sign. Knowledge of these GI manifestations can help make an early diagnosis and establish a management strategy with prompt immunosuppressive treatment.

| 1. | Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, Bacon PA, Churg J, Gross WL, Hagen EC, Hoffman GS, Hunder GG, Kallenberg CG. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:187-192. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1512-1523. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ha HK, Lee SH, Rha SE, Kim JH, Byun JY, Lim HK, Chung JW, Kim JG, Kim PN, Lee MG. Radiologic features of vasculitis involving the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 2000;20:779-794. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Pagnoux C, Mahr A, Cohen P, Guillevin L. Presentation and outcome of gastrointestinal involvement in systemic necrotizing vasculitides: analysis of 62 patients with polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, Wegener granulomatosis, Churg-Strauss syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis-associated vasculitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2005;84:115-128. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Müller-Ladner U. Vasculitides of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15:59-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Morgan MD, Savage CO. Vasculitis in the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:215-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Passam FH, Diamantis ID, Perisinaki G, Saridaki Z, Kritikos H, Georgopoulos D, Boumpas DT. Intestinal ischemia as the first manifestation of vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2004;34:431-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rits Y, Oderich GS, Bower TC, Miller DV, Cooper L, Ricotta JJ, Kalra M, Gloviczki P. Interventions for mesenteric vasculitis. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:392-400.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hokama A, Kinjo F, Arakaki T, Matayoshi R, Yonamine Y, Tomiyama R, Sunagawa T, Makishi T, Kawane M, Koja K. Pulseless hematochezia: Takayasu's arteritis associated with ulcerative colitis. Intern Med. 2003;42:897-898. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Farrant M, Mason JC, Wong NA, Longman RJ. Takayasu's arteritis following Crohn's disease in a young woman: any evidence for a common pathogenesis? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:4087-4090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hokama A, Kinjo F, Hirata T. Image of the month. Churg-Strauss syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:642, 945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pavone L, Grasselli C, Chierici E, Maggiore U, Garini G, Ronda N, Manganelli P, Pesci A, Rioda WT, Tumiati B. Outcome and prognostic factors during the course of primary small-vessel vasculitides. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1299-1306. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zhang Y, Huang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1038-1043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Esaki M, Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, Kawasaki M, Iwai K, Hirakawa K, Tarumi K, Yao T, Iida M. GI involvement in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:920-923. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Hokama A, Shimoji K, Nakamura M, Chinen H, Kishimoto K, Hirata T, Kinjo F, Fujita J. An uncommon cause of haematochezia in an adult with skin rash. Gut. 2008;57:1430, 1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sultan SM, Ioannou Y, Isenberg DA. A review of gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999;38:917-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mok CC. Investigations and management of gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2005;19:741-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ju JH, Min JK, Jung CK, Oh SN, Kwok SK, Kang KY, Park KS, Ko HJ, Yoon CH, Park SH. Lupus mesenteric vasculitis can cause acute abdominal pain in patients with SLE. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:273-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee JR, Paik CN, Kim JD, Chung WC, Lee KM, Yang JM. Ischemic colitis associated with intestinal vasculitis: histological proof in systemic lupus erythematosus. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3591-3593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tian XP, Zhang X. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: insight into pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2971-2977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sakane T, Takeno M, Suzuki N, Inaba G. Behçet's disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1284-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1288] [Cited by in RCA: 1247] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Chung SY, Ha HK, Kim JH, Kim KW, Cho N, Cho KS, Lee YS, Chung DJ, Jung HY, Yang SK. Radiologic findings of Behçet syndrome involving the gastrointestinal tract. Radiographics. 2001;21:911-24; discussion 924-926. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Hokama A, Yamashiro T, Kinjo F, Saito A. Behçet's colitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:239. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Moon CM, Cheon JH, Shin JK, Jeon SM, Bok HJ, Lee JH, Park JJ, Hong SP, Kim TI, Kim NK. Prediction of free bowel perforation in patients with intestinal Behçet's disease using clinical and colonoscopic findings. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:2904-2911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Mor A, Pillinger MH, Wortmann RL, Mitnick HJ. Drug-induced arthritic and connective tissue disorders. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2008;38:249-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lidar M, Lipschitz N, Langevitz P, Shoenfeld Y. The infectious etiology of vasculitis. Autoimmunity. 2009;42:432-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fain O, Hamidou M, Cacoub P, Godeau B, Wechsler B, Pariès J, Stirnemann J, Morin AS, Gatfosse M, Hanslik T. Vasculitides associated with malignancies: analysis of sixty patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1473-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ehrenfeld M, Abu-Shakra M, Buskila D, Shoenfeld Y. The dual association between lymphoma and autoimmunity. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:750-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Buggiani G, Krysenka A, Grazzini M, Vašků V, Hercogová J, Lotti T. Paraneoplastic vasculitis and paraneoplastic vascular syndromes. Dermatol Ther. 2010;23:597-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gandhi MK, Khanna R. Human cytomegalovirus: clinical aspects, immune regulation, and emerging treatments. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:725-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 406] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hokama A, Taira K, Yamamoto Y, Kinjo N, Kinjo F, Takahashi K, Fujita J. Cytomegalovirus gastritis. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;2:379-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hoshino K, Shibata D, Miyagi T, Yamamoto Y, Arakaki S, Maeshiro T, Hokama A, Kinjo F, Takahashi K, Fujita J. Cytomegalovirus-associated gastric ulcers in a patient with dermatomyositis treated with steroid and cyclophosphamide pulse therapy. Endoscopy. 2011;43 Suppl 2 UCTN:E277-E278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Hokama A, Tanaka K, Nakamoto M, Uchima N, Kinjo F, Saito A. An unusual cause of rectal bleeding in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Gut. 2005;54:1061, 1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Zeino Z, Sisson G, Bjarnason I. Adverse effects of drugs on small intestine and colon. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;24:133-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewers: David Friedel, MD, Gastroenterology, Winthrop University Hospital, 222 Station Plaza North, Suite 428, Mineola NY 11501, United States; Young-Tae Bak, MD, PhD, Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Korea UniversityGuro Hospital, 97 Gurodong-gil, Guro-gu, Seoul 152-703, South Korea

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Yang XC