Published online May 16, 2011. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v3.i5.95

Revised: April 23, 2011

Accepted: April 30, 2011

Published online: May 16, 2011

AIM: To compare band ligation (BL) with endoscopic sclerotherapy (SCL) in patients admitted to an emergency unit for esophageal variceal rupture.

METHODS: A prospective, randomized, single-center study without crossover was conducted. After endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal variceal rupture, patients were randomized into groups for SCL or BL treatment. Sclerotherapy was performed by ethanolamine oleate intravascular injection both above and below the rupture point, with a maximum volume of 20 mL. For BL patients, banding at the rupture point was attempted, followed by ligation of all variceal tissue of the distal esophagus. Primary outcomes for both groups were initial failure of bleeding control (5 d), early re-bleeding (5 d to 6 wk), and complications, including mortality. From May 2005 to May 2007, 100 patients with variceal bleeding were enrolled in the study: 50 SCL and 50 BL patients. No differences between groups were observed across gender, age, Child-Pugh status, presence of shock at admission, mean hemoglobin levels, and variceal size.

RESULTS: No differences were found between groups for bleeding control, early re-bleeding rates, complications, or mortality. After 6 wk, 36 (80%) SCL and 33 (77%) EBL patients were alive and free of bleeding. A statistically significant association between Child-Pugh status and mortality was found, with 16% mortality in Child A and B patients and 84% mortality in Child C patients (P<0.001).

CONCLUSION: Despite the limited number of patients included, our results suggest that SCL and BL are equally efficient for the control of acute variceal bleeding.

- Citation: Luz GO, Maluf-Filho F, Matuguma SE, Hondo FY, Ide E, Melo JM, Cheng S, Sakai P. Comparison between endoscopic sclerotherapy and band ligation for hemostasis of acute variceal bleeding. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2011; 3(5): 95-100

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v3/i5/95.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v3.i5.95

Although the superiority of band ligation (BL) over endoscopic sclerotherapy (SCL) for the secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage has been proven, the best approach for acute bleeding remains controversial. The international Baveno IV consensus[1] on portal hypertension recommends band ligation as a first-choice therapy, leaving sclerotherapy as a second-choice procedure. Ligation leads to lower complication rates and higher survival rates[2,3].

A recent meta-analysis suggested that sclerotherapy should remain as the first-choice therapy for cases of bleeding[4]. According to Triantos and colleagues[4], sclerosing agents can be injected by a catheter through the endoscope working channel immediately after the endoscopic diagnosis of esophageal variceal rupture is made. Still, these authors report that when band ligation is employed, it is necessary to withdraw the endoscope for system assembly, potentially increasing complication risk and procedural time.

Conversely, endoscopic SCL performed through the intravascular injection of a 2.5% ethanolamine oleate solution has been used in the majority of Brazilian GI endoscopy units as a low-cost, efficient procedure that is technically easy to perform[5].However, neither of these techniques has been clearly established as the best endoscopic therapy for acute variceal hemorrhage; this fact motivated the current study.

The primary outcome analyzed in this trial was the rate of survival, free of variceal hemorrhage, 6 wk after the index bleeding episode. We calculated that in order to prove a difference of 15% (i.e., 90% vs 75%) in the primary outcome between the groups (BL and SCL) with a power of 80% and a significance level lower than 5%, each group should contain at least 112 patients. Failure of bleeding control and early re-bleeding (see “definitions” section below) were considered secondary outcomes.

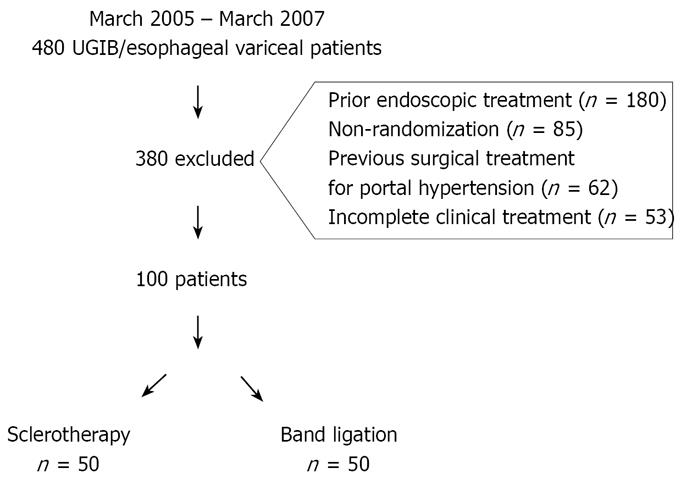

From May 2005 to May 2007, 480 patients with bleeding secondary to esophageal variceal rupture were treated in the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit of the Hospital das Clínicas of São Paulo University Medical School (HC-FMUSP) in São Paulo, Brazil. Of this total, 380 patients were excluded from the study for a number of reasons (Figure 1).

One hundred patients participated in this study, 50 in the SCL group and 50 in the BL group. Patients older than 18 years and with signs of upper GI bleeding for more than 24 h (confirmed hematemesis and melena) were considered candidates for inclusion.

Acute variceal bleeding was defined when endoscopy indicated active bleeding or the presence of a platelet-fibrin plug or gastric fundus with fresh blood, recent clots, and presence of varices, with no other potential source of hemorrhage.

Whenever endoscopy revealed signs of bleeding secondary to the esophageal variceal rupture, patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups: endoscopic sclerotherapy or band ligation. Patients were randomized through a drawing of 100 sealed envelopes under the principle of concealed allocation. All endoscopic procedures were performed by attending physicians or residents under supervision. All patients included in this study were treated with terlipressin (2-4 mg bolus followed by a 2 mg IV maintenance dose every 4 h) and antibiotics (third generation cephalosporin or quinolone) maintained for 5 d or 48 h without signs of re-bleeding.

Sclerotherapy was performed according to the technique adopted in the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit of HC-FMUSP. An injection of 2.5% ethanolamine-oleate was used. The sclerosing solution was injected into the lumen of the hemorrhagic varix at 5 mL increments above and below the rupture point. The maximum volume used per session was 20 mL. If randomization indicated band ligation as treatment, the endoscope was withdrawn from the patient for assembly of the six-shooter multi-band kit (MBL-6, Cook Inc., Winston-Salem, USA). Attempts were made to ligate the varix on the rupture point while also treating the other varices with the remaining bands. Whenever the exact rupture point could not be identified, ligation of all variceal tissue visible in the final 5 cm of the esophagus was performed with six elastic bands.

This study was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the Gastroenterology Department of São Paulo University Medical School (FMUSP) and by the Ethics Committee for Research Project Analysis (CAPPesp) of the Clinical Board of Hospital das Clínicas and FMUSP. All patients, or their legal representatives, signed informed consent forms.

In order to evaluate the efficacy of both treatments, groups were compared regarding failure in bleeding control (up to 5 d), early recurrence of bleeding (5 d and 6 wk), complications, and mortality.

Failure in bleeding control was defined as the failure to control bleeding at the moment of examination, or the occurrence of re-bleeding or mortality within the first 5 d after the procedure. Failure criteria included the need for a change in technique in order to achieve hemostasis, the presence of hematemesis, or the presence of fresh blood in the nasogastric tube aspirate associated with signs of hemodynamic instability (systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg and/or pulse > 100 bpm), or a 3-point hemoglobin level decrease within a 6 h period. Only severe locoregional complications derived from the endoscopic treatment involving surgical treatment or a longer hospital stay were considered, e.g., dissecting hematoma, dysphagia, hemorrhagic ulcer, perforation, mediastinitis, or esophageal stenosis. Bleeding-related mortality was defined as any death occurring between admission and 6 wk after admission[1].

After endoscopic treatment, patients were followed up for 6 wk through bedside appointments or telephone contact (with patients discharged before 6 wk) for analysis of re-bleeding, complications, and mortality. Whenever permitted by clinical conditions, secondary prophylaxis with band ligation (independent from the allocation group) was indicated on the 14th day after the initial procedure.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients from both groups are presented in Table 1.

| Ligationn = 50 | Sclerotherapyn = 50 | ||

| Mean age (years) | 54.48 | 50.24 | P1 = 0.47 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 37 (74.0) | 35 (70.0 ) | P2 = 0.58 |

| Female | 13 (26.0) | 15 (30.0 ) | |

| Etiology | |||

| Alcohol | 19 (38.0) | 17 (34.0) | P2 = 0.83 |

| Virus | 19 (38.0) | 15 (30.0) | P2 = 0.53 |

| Schistosomiasisa | 6 (12.0) | 11 (22.0) | P2 = 0.29 |

| Secondary biliary cirrhosis | 4 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) | P2 = 0.99 |

| Cryptogenic cirrhosis | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.0) | P2 = 0.99 |

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 1(2.0) | 2 (4.0) | P2 = 0.99 |

| Child-Pugh Classification | |||

| Child A | 2 ( 4.0) | 3 (6.0) | |

| Child B | 22 (44.0) | 21 (42.0) | P1 =0.69 |

| Child C | 20 (40.0) | 15 (30.0) |

Hemorrhage intensity was assessed as mild, moderate, or severe according to the criteria proposed by Johnston et al[6]. The classification of digestive hemorrhage intensity according to these criteria[6] is summarized in Table 2.

| Band Ligation (n=50) | Sclerotherapy (n =50) | ||

| Size of Varices | |||

| Small | 10 | 13 | |

| Medium | 5 | 7 | |

| Large | 5 | 4 | |

| Small/Medium | 17 | 17 | |

| Small/Large | 2 | 2 | |

| Medium/Large | 11 | 7 | |

| Digestive hemorrhage intensity | |||

| Mild | 15 (30) | 17 (34) | |

| Moderate | 20 (40) | 19 (38) | P = 0.32 |

| Severe | 15 (30) | 14 (28) | |

| Hemoglobin at admission | |||

| mean ± SD | 9.52 ± 3.25 | 9.47 ± 2.55 | P = 0.96 |

| Red spots | |||

| Presence | 46(92.8) | 43(86.8) | P = 0.64 |

| Absence | 4 (8.8) | 7 (14.8) | |

| Endoscopic criteria for variceal bleeding | |||

| Active bleeding | 5 (10) | 10 (20) | |

| Platelet-fibrin plug | 35 (70) | 34 (68) | P = 0.43 |

| Varices and gastric blood | 10 (20) | 6 (12) |

During endoscopic examination, the caliber of esophageal varices was classified as small, medium, or large (alternatively, this assessment was made according to the descriptions made by the performing physicians) according to Paquet’s classification[7].

Red spots on variceal cords were subjectively classified as present or absent by the examining physician. The frequency of red spots is presented in Table 2, as are the mean values for hemoglobin levels at admission and the frequency of endoscopic appearance of variceal hemorrhage.

A student’s t test was used for the comparison of means with normal distribution variables, and a Mann-Whitney test was used for means without normal distribution. A chi-square test was used to verify associations in contingency tables (occurrence data). A Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze these results, namely, the comparisons of the frequencies observed in variables across the BL and SCL groups. Effects with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

One hundred patients participated in this study, 50 in the SCL group and 50 in the BL group.

The rate of failure in bleeding control (up to 5 d) is shown in Table 3. Results did not differ when patients with schistosomiasis were excluded from the analysis (Table 4).

| Group | Re-bleeding | Success | Mortality |

| Sclerotherapy (n = 50) | 7 (14.0) | 43 (86.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Band Ligation (n = 50) | 11 (22.0) | 39 (78.0) | 6 (12.0) |

| Group | Success | Re-bleeding | Mortality |

| Sclerotherapy (n = 39) | 33 (84.6) | 6 (15.4) | 3 (7.7) |

| Band Ligation (n = 44) | 33 (75.0) | 11 (25.0) | 6 (13.6) |

| P = 0.41 | P = 0.49 |

Among the 50 patients who underwent endoscopic SCL, seven (14%) presented re-bleeding within a 5-day period. In the BL group, 11 (22%) patients presented re-bleeding during the same period. For the 50 patients treated with BL, 218 elastic bands were applied, ranging from 3 to 6 bands per patient with an average of 4 bands per procedure.

No association was observed between the occurrence of failure in bleeding control and endoscopic treatment (P = 0.2978). Among the patients who presented re-bleeding in the SCL group, one (2%) had schistosomiasis, two (4%) had Child-Pugh B cirrhosis, and four (8%) had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. Likewise, among those with failure in bleeding control in the BL group, four (8%) had Child-Pugh B cirrhosis, and seven (14%) had Child-Pugh C cirrhosis. Among the total number of patients who presented re-bleeding within 5 d (18 patients), 11 (61.11%) were Child-Pugh C patients. The difference between the Child-Pugh C group and the other Child-Pugh groups regarding failure occurrence is shown by the results from the Fisher’s exact test. The probability of a Child-Pugh C patient re-bleeding within this period was 3.74-fold higher than that of a Child-Pugh A or B patient.

Among SCL patients with treatment failure, two (4%) presented failure in immediate hemostasis, requiring a change of technique to achieve hemostasis after endoscopic SCL. Bleeding in one patient was controlled through the use of cyanoacrylate. The second patient underwent esophageal balloon tamponade, which was withdrawn after 18 h, at which time a new endoscopic SCL was successfully performed. In the BL group, immediate failure during the procedure occurred in four patients (8%). The first patient was treated with complementation through endoscopic SCL. The second patient received a cyanoacrylate injection. The third patient underwent esophageal balloon tamponade, and the fourth patient underwent tamponade for 12 h, followed by cyanoacrylate injection after balloon withdrawal, and was immediately referred for trans-jugular, intra-hepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) placement evolving without re-bleeding through a 6-week follow-up.

Between 5 d and 6 wk after the procedure, 42 SCL and 37 BL patients were considered for early re-bleeding analysis. This number excludes those patients who died in the first period (up to 5 d), as well as five SCL and seven BL patients who were lost to follow-up. Among the SCL group, two (4.8%) patients presented re-bleeding after 5 d, 36 patients (86%) survived until the end of the study, and six patients (14%) died after 5 d. In the BL group, one (2.7%) patient presented re-bleeding after 5 d, 33 (89%) survived until the end of the study, and four (11%) died (Table 5).

| Group | Re-bleeding | Success | Mortality |

| Sclerotherapy (n = 42) | 2 (4.8) | 36 (86.0) | 6 (14.0) |

| Band Ligation (n = 37) | 1 (2.7) | 33 (89.0) | 4 (11.0) |

No additional endoscopic treatment-derived complications were observed.

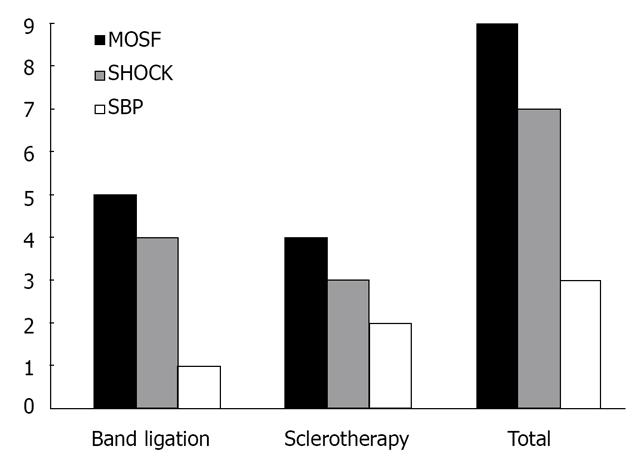

Of 88 follow-up patients, 19 (21.6%) died, nine (20%) from the SCL group and 10 (23%) from the BL group (Table 6). Of these 19 deceased patients, three (16%) were Child-Pugh B, and 16 (84%), Child-Pugh C patients (P < 0.001).

| Group | Deaths through 6 wk | |||

| Mortalityup to 5 d | Mortality after 5 d | Total Mortality | Success | |

| Sclerotherapy (n = 45) | 3 (7.0) | 6 (13.0) | 9 (20.0) | 36 (80.0) |

| Band Ligation (n = 43) | 6 (14.0) | 4 (9.0) | 10 (23.0) | 33 (77.0) |

| P = 0.40 | ||||

Among patients who presented active bleeding on endoscopic examination (n = 15), 10 (66%) were from the SLC group, and five (34%) were from the BL group. Among this subgroup of patients, 33% mortality was observed up to 6 wk (two SCL and three BL patients), with no difference between groups (P = 0.186). The causes of death among groups are presented in Figure 2.

The general improvement in the results of the treatment of variceal acute bleeding might be attributed to better clinical management of these patients. The use of vasoactive drugs and antibiotic prophylaxis is currently mandatory for patients with variceal bleeding. Antibiotic therapy reduced the infection rate from 45% to 14%[8], bleeding recurrence from 44% to 18%[9], and mortality rate from 48% to 15%[8]. Terlipressin was found to be as effective as an endoscopic treatment with an efficacy of 80% for acute variceal bleeding control within the first 48 hours[10].

Although the highest-level recommendation of the use of antibiotics and vasoactive drugs in the treatment of acute variceal rupture episodes is already established in the literature[11], no consensus exists regarding the preferred endoscopic treatment: band ligation or sclerotherapy.

Sclerotherapy has proven to be inferior to band ligation for primary and secondary prophylaxes of variceal hemorrhage, due to a higher number of complications, and the fact that more sessions are required to achieve variceal obliteration[12,13]. However, endoscopic SCL has still been found to be similar to BL for control of bleeding in some studies[4].

Band ligation, described by Stiegmann and colleagues[14] in 1986, acts by mechanical action; it causes the strangulation of the variceal cord, resulting in necrosis and scar formation 7-10 d later. The technical difference is provided by the number of elastic bands used, and up to 10 bands may be used in a single endoscopic procedure. Because this technique is relatively easy to perform, results are generally reproducible and homogeneous.

In contrast to BL, the intravariceal injection of sclerosing agents was the first endoscopic treatment used, nearly 50 years before the introduction of the elastic band device[15]. There are a number of variations in the endoscopic sclerosing technique, including the type of sclerosing agent used, its concentration, injected volume, and injection location (intravascular, paravascular or combined), which is reflected in the heterogeneous results of SCL presented in different publications. Moreover, this technique requires significant experience and skill of the endoscopist, and it is thus a more operator-dependent technique than band ligation.

A meta-analysis comparing the use of sclerotherapy and band ligation was published in 2006[4]. This analysis involved 12 studies with a total of 1309 patients. The efficacy of endoscopic SCL for initial hemostasis was found to be on average 95% (76%-100%), whereas BL efficacy was found to be 97% (86%-100%). Despite the better results in bleeding control obtained by band ligation, no difference in mortality was found, and these authors concluded that both band ligation and sclerotherapy can be used for the control of acute variceal hemorrhage.

A comparison of 5% ethanolamine-oleate sclerotherapy with band ligation for the treatment of acute variceal bleeding was conducted in 2006[3] in 179 patients (89 in the endoscopic SCL group and 90 in the BL group). Treatment failure occurred in 24% of SCL patients and in 10% of BL patients (relative risk: 2.4%). The major adverse effect rate was found to be 13% for those receiving endoscopic SCL and 4% for those in the BL group (P = 0.04). Despite the superior efficacy and safety of band ligation, the 6-week survival likelihood was similar for both groups (P = 0.17), with 19 deaths (21%) among SCL patients and 12 deaths (13%) among BL patients.

In the present study, the efficacy of bleeding control within the first 5 days was found to be 86% in the SCL group and 78% in the BL group (P = 0.30). Mortality within 6 wk was found to be 20% in the SCL group (9 patients) and 23% in the BL group (10 patients), figures similar to those found in the literature. Local adverse effects caused by SCL, such as hemorrhagic ulcer and perforation, are actually described in the literature more often[3] than was observed in this study. This suggests the refinement of the endoscopic sclerosis technique used in the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit at Hospital das Clínicas of São Paulo University Medical School. An example of this refinement is the use of a sclerosing agent diluted to 2.5%, rather than the 5% employed in other studies[3].We also advocate the use of the intravascular technique and a maximum injection volume of 20 mL.

The Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Unit of HC-FMUSP has amassed over 30 years of experience using sclerotherapy for esophageal variceal treatment. The benefit of endoscopic SCL for patients with schistosomiasis, with a 95% efficacy rate in bleeding control, was demonstrated by Sakai and colleagues[5] in 1990. The importance of hepatic function in the results of endoscopic SCL was described by these authors in another study conducted in 1988[16]. Band ligation, conversely, was introduced in this unit for acute variceal bleeding control in 2004. The greater experience with SCL than BL in this unit might have favored the results of endoscopic sclerosis. It is well recognized that the presence of the distal cap with the bands reduces the endoscopic field which is specially critical during active bleeding.

In this study, 17 (17%) patients presented with liver schistosomiasis, which causes pre-sinusoidal, intra-hepatic portal hypertension with minimal damage to liver function. Due to the patient randomization process, these patients made up 22% of the sclerotherapy group and 12% of the banding group (P = 0.29). This uneven distribution of schistosomiasis patients could also have favored the results of the sclerotherapy group. However, no change in the results was observed when these patients were excluded from the analysis.

Failure in bleeding control and mortality were found to be more frequent in Child-Pugh C patients. Of the 18 patients who presented re-bleeding within the first 5 d, 11 (61.1%) were Child-Pugh C patients; 16 (84%) of the total deaths in the 6-week period (19 patients) were also Child-Pugh C patients. Mortality in this subgroup at the end of 6 wk was found to reach 45.7% (45% in the BL and 46.6% in the SCL group).

A comparative analysis of endoscopic sclerosis with ethanolamine-oleate and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Hystoacril®) injection for acute bleeding control in Child-Pugh C cirrhotic patients demonstrated that significant improvement can be seen with the use of Hystoacril®, according to a study conducted by our group[17] in 2001. Although Hystoacril® is traditionally recommended in patients with gastric varices[1,18], its use for esophageal varices in Child-Pugh C patients improves bleeding control results[17]. This technique has not been widely used, probably due to the risk of damage to the endoscope. Furthermore, the substance has yet to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this specific purpose and, therefore, is not used in the US. In Brazil, its registration has been approved by the national drug regulatory agency.

The economic perspective on the treatment of this complication from portal hypertension should be emphasized. A ligation device with six elastic bands currently costs $400.00 on average. In comparison, a sclerosis needle costs approximately $100.00, and the sclerosing substance costs approximately $10.00. In a setting where financial resources allocated to healthcare are scarce, the use of this less costly but similarly efficient technique is a sensible choice.

The present study was clearly too small to prove the tested hypothesis, due to the major difficulty in finding patients appropriate for inclusion in this trial. Several patients were sent to our academic tertiary referral center by other smaller hospitals, but endoscopic treatment at other locations or the absence of previous adequate clinical management precluded their inclusion in the trial. Despite the abovementioned limitations, our results suggest that sclerotherapy should not be dismissed as a possible alternative treatment of rupture of esophageal varices.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding caused by rupture of esophageal varices is a common and feared complication of hepatic cirrhosis and portal hypertension. It carries a high mortality rate. The accepted treatment of the acute bleeding episode involves the use of vasoactive drugs and endoscopic treatment. Among possible endoscopic treatments, the applications of elastic bands (banding) and the injection of sclerosing agents into the varix (sclerotherapy) have been studied. For the acute bleeding episode it is not clear whether banding is superior to sclerotherapy for the definitive hemostasis.

In the area of endoscopic treatment of acute variceal bleeding, one of the research hotspots is to compare endoscopic banding and endoscopic sclerotherapy for definitive hemostasis and hospital mortality.

In the present study, the authors conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic banding and endoscopic sclerotherapy for the treatment of the acute bleeding episode of esophageal variceal rupture.

The study results suggest that both treatments are equally effective for the treatment of bleeding caused by esophageal varices.

The authors preformed a single center randomized clinical trial comparing sclerotherapy and band ligation for the control of acute variceal bleeding. The trial was terminated prematurely before the calculated patient number estimated to need to prove a 15% difference in the primary endpoint (survival) was recruited, due to difficulties in patient recruitment. This is an interesting study on an important problem for all interventional gastrointestinal endoscopists.

| 1. | de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005;43:167-176. |

| 2. | Laine L, Cook D. Endoscopic ligation compared with sclerotherapy for treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:280-287. |

| 3. | Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, Gómez C, López-Balaguer JM, Gonzalez B, Gallego A, Torras X, Soriano G, Sáinz S. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45:560-567. |

| 4. | Triantos CK, Goulis J, Patch D, Papatheodoridis GV, Leandro G, Samonakis D, Cholongitas E, Burroughs AK. An evaluation of emergency sclerotherapy of varices in randomized trials: looking the needle in the eye. Endoscopy. 2006;38:797-807. |

| 5. | Sakai P, Boaventura S, Ishioka S, Mies S, Sette H, Pinotti HW. Sclerotherapy of bleeding esophageal varices in schistosomiasis. Comparative study in patients with and without previous surgery for portal hypertension. Endoscopy. 1990;22:5-7. |

| 6. | Johnston SJ, Jones PF, Kyle J, Needham CD. Epidemiology and course of gastrointestinal haemorrhage in North-east Scotland. Br Med J. 1973;3:655-660. |

| 7. | Paquet KJ, Oberhammer E. Sclerotherapy of bleeding oesophageal varices by means of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1978;10:7-12. |

| 8. | Bernard B, Grangé JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1655-1661. |

| 9. | Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Kuo BI, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. Antibiotic prophylaxis after endoscopic therapy prevents rebleeding in acute variceal hemorrhage: a randomized trial. Hepatology. 2004;39:746-753. |

| 10. | Ioannou GN, Doust J, Rockey DC. Systematic review: terlipressin in acute oesophageal variceal haemorrhage. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:53-64. |

| 11. | Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-938. |

| 12. | van Buuren HR, Rasch MC, Batenburg PL, Bolwerk CJ, Nicolai JJ, van der Werf SD, Scherpenisse J, Arends LR, van Hattum J, Rauws EA. Endoscopic sclerotherapy compared with no specific treatment for the primary prevention of bleeding from esophageal varices. A randomized controlled multicentre trial [ISRCTN03215899]. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:22. |

| 13. | Garcia-Pagán JC, Bosch J. Endoscopic band ligation in the treatment of portal hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:526-535. |

| 14. | Van Stiegmann G, Cambre T, Sun JH. A new endoscopic elastic band ligating device. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:230-233. |

| 15. | Craaford C, Frenckner P. New surgical treatment of varices veins of the esophagus. Acta Otolaryngol. 1939;27:422-429. |

| 16. | Sakai P, Boaventura S, Capacci ML, Macedo TM, Ishioka SZ. Endoscopic sclerotherapy of bleeding esophageal varices. A comparative study of results in patients with schistosomiasis and cirrhosis. Endoscopy. 1988;20:134-136. |

| 17. | Maluf-Filho F, Sakai P, Ishioka S, Matuguma SE. Endoscopic sclerosis versus cyanoacrylate endoscopic injection for the first episode of variceal bleeding: a prospective, controlled, and randomized study in Child-Pugh class C patients. Endoscopy. 2001;33:421-427. |

| 18. | Marques P, Maluf-Filho F, Kumar A, Matuguma SE, Sakai P, Ishioka S. Long-term outcomes of acute gastric variceal bleeding in 48 patients following treatment with cyanoacrylate. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:544-550. |

Peer reviewers: Christoph Eisenbach, MD, Department of Gastroenterology, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 410, D-69210 Heidelberg, Germany; Peter Born, Professor, Chief, 2nd Department of Medicine, Red Cross Hospital, Munich, Germany

S-Editor Wang JL L-Editor Herholdt A E-Editor Zhang L