Published online May 16, 2010. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v2.i5.190

Revised: March 23, 2010

Accepted: March 30, 2010

Published online: May 16, 2010

Choledochal varices are a rare cause of hemobilia associated with chronic portal vein thrombosis. We present a case of chronic portal vein thrombosis complicated with bleeding from choledochal varices. The presentation, clinical manifestations and management are described.

- Citation: Ng CH, Lai L, Lok KH, Li KK, Szeto ML. Choledochal varices bleeding: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 2(5): 190-192

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v2/i5/190.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v2.i5.190

Choledochal varices should be considered as a possible cause of obstructive jaundice in patients with history of portal vein thrombosis or hypertension. Diagnosis of choledocal varices can be easily missed by the usual imaging procedures. Unrecognized choledochal varices can lead to bleeding during endoscopic biliary tract procedures. We report a case of bleeding choledochal varices with biliary tree obstruction secondary to chronic portal vein thrombosis. The contribution of endoscopic ultrasound findings towards making a prompt diagnosis is emphasized.

A 53 year old man was admitted to hospital with splenomegaly and thrombocythemia in 2001. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen revealed splenomegaly and the absence of blood flow in the main portal vein which suggested portal vein thrombosis. Bone marrow biopsy showed trilineage hyperplasia which suggested myeloproliferative disease. He experienced an episode of esophageal varices bleeding in 2001 which was controlled with multiple banding ligations. He was followed up in the hematology clinic and given hydroxyurea 500 mg daily and propanolol 20 mg three times daily. His regular surveillance endoscopy did not show recurrence of esophageal varices.

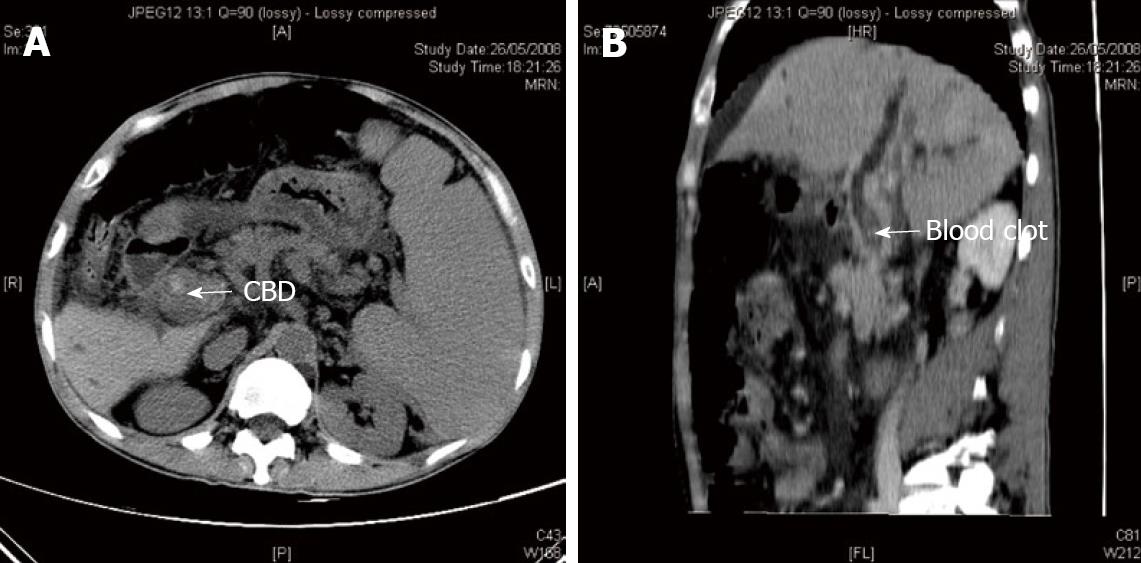

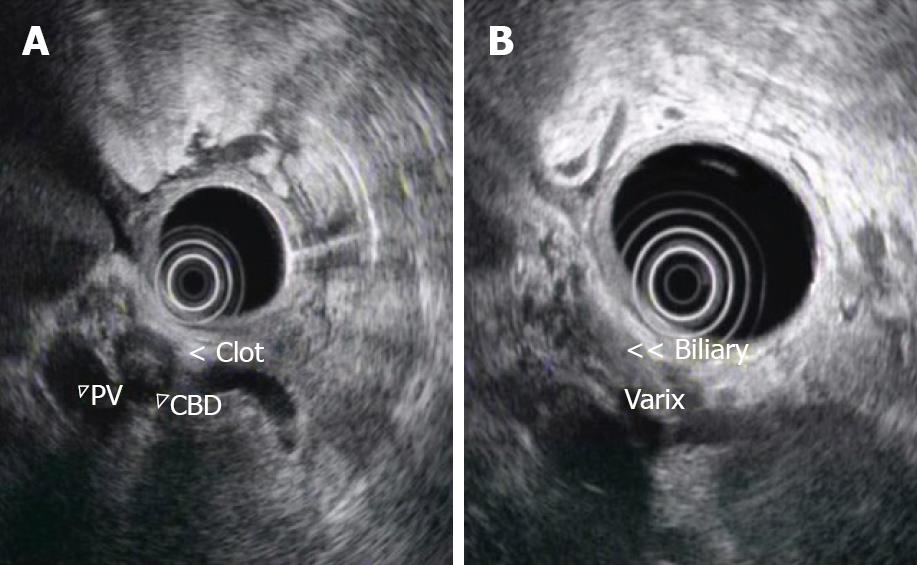

In May 2008 he presented with a 2 d history of rectal bleeding. On admission, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. Physical examination showed only splenomegaly and a fresh blood clot in the rectum. Blood tests revealed hemoglobin 10.6 g/dL (reference level 13-18 g/dL), platelets 225 × 109/L (reference level 150 - 400 × 109/L) and total bilirubin 61 μmol/L (reference level 2-23 μmol/L). Serum alanine transferase, alkaline phosphatase and prothrombin time were normal. An upper esophageal gastroduodenoscopy was performed one day after admission. There were three columns of small esophageal varices with no evidence of recent bleeding. No gastric varix was detected. However, active spurting through the ampulla of Vater was noted. Computer tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed mild biliary tree dilatation with intraluminal hyperdensities that suggested a blood clot (Figure 1A and B). Features of chronic portal hypertension which include ascites, splenomegaly, portal venous thrombosis and portasystemic collaterals were seen. No definite liver mass suggestive of a liver tumor was seen. He was given intravenous terlipressin injections and the bleeding subsided after medical therapy. Four days after admission, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) of the biliary system showed echogenic material with acoustic shadow, consistent with a blood clot inside the common bile duct (Figure 2A). In addition, there were multiple collaterals around the duodenum and common bile duct (Figure 2B) and the main portal vein was occluded. There was no pancreatic mass and no mass extension outside the common bile duct. The splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein were patent. However, he developed a fever, chill and shock on the same day after the EUS. Blood tests showed evidence of cholangitis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. His clinical course was complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure despite percutaneous biliary tree drainage. He died 9 d after admission.

We described a man with chronic extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis and choldedochal varices secondary to an underlying haematological thrombotic tendency. He had bleeding from bile duct varices complicated by obstructive jaundice. He died due to cholangitis and multi-organ failure.

There are several causes of hemobilia. Experience from Green’s series[1] indicate that trauma during medical procedures is the most common etiology of haemobilia. Other causes include inflammation, gallstone disease, vascular abnormalities and tumor. Bleeding from bile duct varices is relatively rare and to our knowledge, less than 10 case series have been reported[2,3].

Bile duct varices result from abnormal venous dilatation of the bile duct wall when the pressure within the main portal vein is elevated. This is particularly observed in the presence of portal vein obstruction. The extrahepatic bile duct is surrounded by two venous systems, namely the paracholedochal veins of Petren[4] and the epicholedochal venous plexus of Saint[5]. The paracholedochal veins are extrinsic to the bile duct wall so dilatation of these veins results in extrinsic compression on the common bile duct. Saint plexus on the other hand, is a fine reticular venous network covering the outer surface of the common hepatic and bile duct. When the portal vein is obstructed, these plexus dilate and bypass the occlusion. Occasionally this abnormal dilated venous structure may bleed and cause mechanical obstruction.

Although choledochal varices may be an incidental finding of imaging, its occurrence can result in several clinical consequences. Firstly, case reports reveal that unrecognized bile duct varices may lead to excessive hemorrhage during surgery of bile duct[6]. Secondly, choledocal varices may compress the bile duct lumen and result in obstruction and jaundice[7]. Moreover, bleeding from the bile duct can be fatal and can be spontaneous or secondary to endoscopic procedure. The possibility of procedure induced bleeding was highlighted by a report of a case of severe bleeding resulting from endoscopic bile duct dilatation[8]. Finally, the variable appearance of choledochal varices on cholangiogram can lead to a diagnostic dilemma. Classically, choledocal varices appear as smooth extrinsic compression on cholangiogram. However, an appearance resembling primary sclerosing cholangitis has been reported. Liver biopsy of these patients showed features of small bile duct disease. One possible explanation is a direct compressive injury to the bile duct by porta cavernoma or ischaemic injury secondary to poor venous drainage. In addition, bile duct angulation and displacement (pseudo cholangiocarcinoma sign) has been reported in the case of bile duct varices which render its differentiation from malignant biliary stricture difficult.

Diagnosis of choledochal varices relies on high clinical suspicion, typical cholangiogram appearances and evidence of extrahepatic portal venous obstruction and collateral venous circulation on imaging. The role of endoscopic ultrasound in diagnosis had been described by Palazzo et al[9]. It is advantageous over other imaging modalities by allowing better visualization of the portal vein and bile duct anatomy and the relationship of the dilated venous collaterals or varices with the bile duct and duodenum. Besides, EUS can also detect unrecognized malignant tumors in patients with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction of undetermined origin or thrombosis that has not been previously recognized in a CT scan[10].

Treatment is usually offered when complications develop. For patients with jaundice due to obstruction by bile duct varices, treatment options include portosystemic shunting and hepaticojejunostomy. Portosystemic shunting can be achieved by transjugular or surgical methods. Regression of bile duct varices following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting has been reported[11]. For a patient presenting with variceal bleeding, both endoscopic sclerotherapy and portasystemic shunting are an effective treatment of choice[12].

In conclusion, we report a case of haemobilia due to choledochal varices complicated with common bile duct obstruction and cholangitis. Choledochal varices should be included in the differential diagnosis of haemobilia or unexplained CBD stricture, especially in the presence of portal hypertension. It is particularly important since unrecognized choledochal varices may result in hemorrhage during endoscopic procedures involving the bile duct.

| 2. | Layec S, D’Halluin PN, Pagenault M, Bretagne JF. Massive hemobilia during extraction of a covered self-expandable metal stent in a patient with portal hypertensive biliopathy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:555-556; discussion 556. |

| 3. | Oo YH, Olliff S, Haydon G, Thorburn D. Symptomatic portal biliopathy: a single centre experience from the UK. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:206-213. |

| 4. | Petren T. The veins of the extrahepatic biliary system and their pathologic-anatomic significance. Verh Anat Ges. 1932;41:139-143. |

| 5. | SAINT JH. The epicholedochal venous plexus and its importance as a means of identifying the common duct during operations on the extrahepatic biliary tract. Br J Surg. 1961;48:489-498. |

| 6. | Dan SJ, Train JS, Cohen BA, Mitty HA. Common bile duct varices: cholangiographic demonstration of a hazardous portosystemic communication. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:42-43. |

| 7. | Perlemuter G, Béjanin H, Fritsch J, Prat F, Gaudric M, Chaussade S, Buffet C. Biliary obstruction caused by portal cavernoma: a study of 8 cases. J Hepatol. 1996;25:58-63. |

| 8. | Tighe M, Jacobson I. Bleeding from bile duct varices: an unexpected hazard during therapeutic ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:250-252. |

| 9. | Palazzo L, Hochain P, Helmer C, Cuillerier E, Landi B, Roseau G, Cugnenc PH, Barbier JP, Cellier C. Biliary varices on endoscopic ultrasonography: clinical presentation and outcome. Endoscopy. 2000;32:520-524. |

| 10. | Lai L, Brugge WR. Endoscopic ultrasound is a sensitive and specific test to diagnose portal venous system thrombosis (PVST). Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:40-44. |

| 11. | Görgül A, Kayhan B, Dogan I, Unal S. Disappearance of the pseudo-cholangiocarcinoma sign after TIPSS. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:150-154. |

| 12. | Ito T, Segawa T, Kanematsu T. Successful endoscopic injection sclerotherapy for bleeding from bile duct varices. Surg Today. 1997;27:174-176. |

Peer reviewer: Satoru Kakizaki, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine and Molecular Science, Gunma University, Graduate School of Medicine, 3-39-15 Showa-machi, Maebashi, Gunma 371-8511, Japan