Published online Jul 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.108082

Revised: April 23, 2025

Accepted: May 26, 2025

Published online: July 16, 2025

Processing time: 95 Days and 4.6 Hours

Endocytoscopy is an advanced imaging modality that provides real-time, ultra-high magnification views of the intestinal mucosa. In ulcerative colitis (UC), the combined assessment of endoscopic and histological remission is now becoming a standard practice. However, histological evaluation typically falls outside the scope of the endoscopist. By offering in vivo microscopic imaging, endocytoscopy has the potential to streamline workflow and enhance efficiency in assessing UC activity.

To evaluate the utility of real-time endocytoscopy in assessing endoscopic and histological disease activity in UC, and to validate endocytoscopic scoring sys

This study was conducted at Concord Hospital. Patients with UC who consented to undergo colonoscopy with endocytoscopy were enrolled. Data collected in

A total of 61 colonic segments from 15 patients were assessed, with 187 analyzable endocytoscopic images. Endocytoscopy showed significant correlation with the MES using both the ECSS (κ = 0.60, P < 0.001; r = 0.78, P < 0.001) and ELECT (κ = 0.88, P < 0.001; r = 0.81, P < 0.001) scoring systems. Similarly, correlations with the Nancy histological index were significant for both ECSS (κ = 0.47, P < 0.001; r = 0.69, P < 0.001) and ELECT (κ = 0.88, P < 0.001; r = 0.74, P < 0.001). The ELECT score demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy in identifying histological remission, with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 85%, and an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.90 (95% confidence interval: 0.78-1.00), compared to 68.3%, 85%, and an area under the receiver ope

Endocytoscopy allows for real-time, simultaneous assessment of endoscopic and histological activity in UC and has been proven to be accurate, safe, and well-tolerated. Compared with the ECSS, the ELECT score showed superior concordance with histological findings.

Core Tip: Endocytoscopy is an advanced imaging technique providing ultra-high magnification for real-time mucosal assessment. This prospective study evaluated its role in simultaneously assessing endoscopic and histological activity in ulcerative colitis. Endocytoscopy score, particularly the ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis score, correlated strongly with standard indices including the Mayo endoscopic score and the Nancy histological index. ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis outperformed the endocytoscopy score in identifying histological remission. These findings support endocytoscopy as a safe, accurate, and efficient tool that may streamline ulcerative colitis disease assessment in daily practice.

- Citation: Chaemsupaphan T, Shir Ali M, Fung C, Paramsothy S, Leong RW. Endocytoscopy in real-time assessment of histological and endoscopic activity in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(7): 108082

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i7/108082.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.108082

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic gastrointestinal disorder that poses a significant global health challenge. IBD primarily includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease, both characterized by relapsing-remitting inflammation, affecting both the small and large intestines[1,2]. Given the chronic nature of IBD, a comprehensive long-term strategy for monitoring disease activity and progression is essential. Regular endoscopic evaluations and histological assessments play a crucial role in managing IBD. These evaluations typically involve colonoscopies, supplemented by biopsies from different regions of the bowel, to facilitate continuous monitoring and allow for timely treatment adjust

Focusing on UC, this chronic inflammatory condition is confined to the colon and is often associated with diarrhea and rectal bleeding[2]. While no curative treatment currently exists, the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease initiative by the International Organization for the Study of IBD has recommended endoscopic healing, defined as a Mayo endoscopic score (MES) of < 1, as a key long-term treatment goal[4]. However, histological remission has increasingly been recognized and emerged as a promising goal due to its association with more sustained long-term remission, including reduced rates of corticosteroids use, hospitalization, and colectomy[5-10]. Histological normalization is also associated with significantly higher odds of relapse-free survival compared to histological quiescence (hazards ratio = 4.31) and presence of histological activity (hazards ratio = 6.69)[7]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 studies, patients who achieved histological remission experienced a 63% reduced risk of clinical relapse than those with persistent histological activity, even if they were in endoscopic remission[5]. Additionally, another meta-analysis of 15 UC studies showed that relapse or exacerbation was significantly less frequent with baseline histological remission (relative risk = 0.48) compared to histological activity, and also lower compared to baseline clinical and endoscopic remission (relative risk = 0.81)[6]. The absence of specific histological features, such as neutrophils in the epithelium, lamina propria, crypt abscesses, and chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate, further reduced the risk of relapse. However, histological outcome is not yet a standard target due to the lack of universally accepted histological reporting methods. Additionally, histological assessment is not real-time, requiring specimen processing, which may delay clinical decision-making. Therefore, having an endoscopy that can assess these microscopic features immediately would be highly advantageous and potentially enhance quality of clinical practice[11].

Endocytoscopy is a high-resolution imaging modality, enabling histology-equivalent visualization of intestinal cell and nuclear morphology. This technique is particularly valuable in the management of IBD, especially UC, as it facilitates the detection of the degree of inflammation and subtle dysplastic changes[12]. By allowing real-time evaluation of histolo

Endocytoscopy score (ECSS), developed in 2011, employing previous-generation device with 450-fold magnification, is a widely used scoring system during the procedure, focusing on crypt shape, crypt distance, and microvasculature visi

We conducted a prospective cross-sectional study of patients diagnosed with UC at Concord Hospital, Sydney, Australia, between December 2023 to April 2024. Participants eligible for this study included UC patients aged > 18 years and scheduled for colonoscopy for different clinical indications, such as disease assessment or dysplasia surveillance. Recruitment was conducted during clinic visits, where detailed information was provided and informed consents were obtained. Patients were excluded from the study if they were medically unfit for a colonoscopy, had a known allergy to methylene blue, were pregnant or breastfeeding, or presented with conditions requiring emergency colonoscopy. Patients unable or unwilling to provide informed consent were also excluded. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics, including disease status, were collected before procedures.

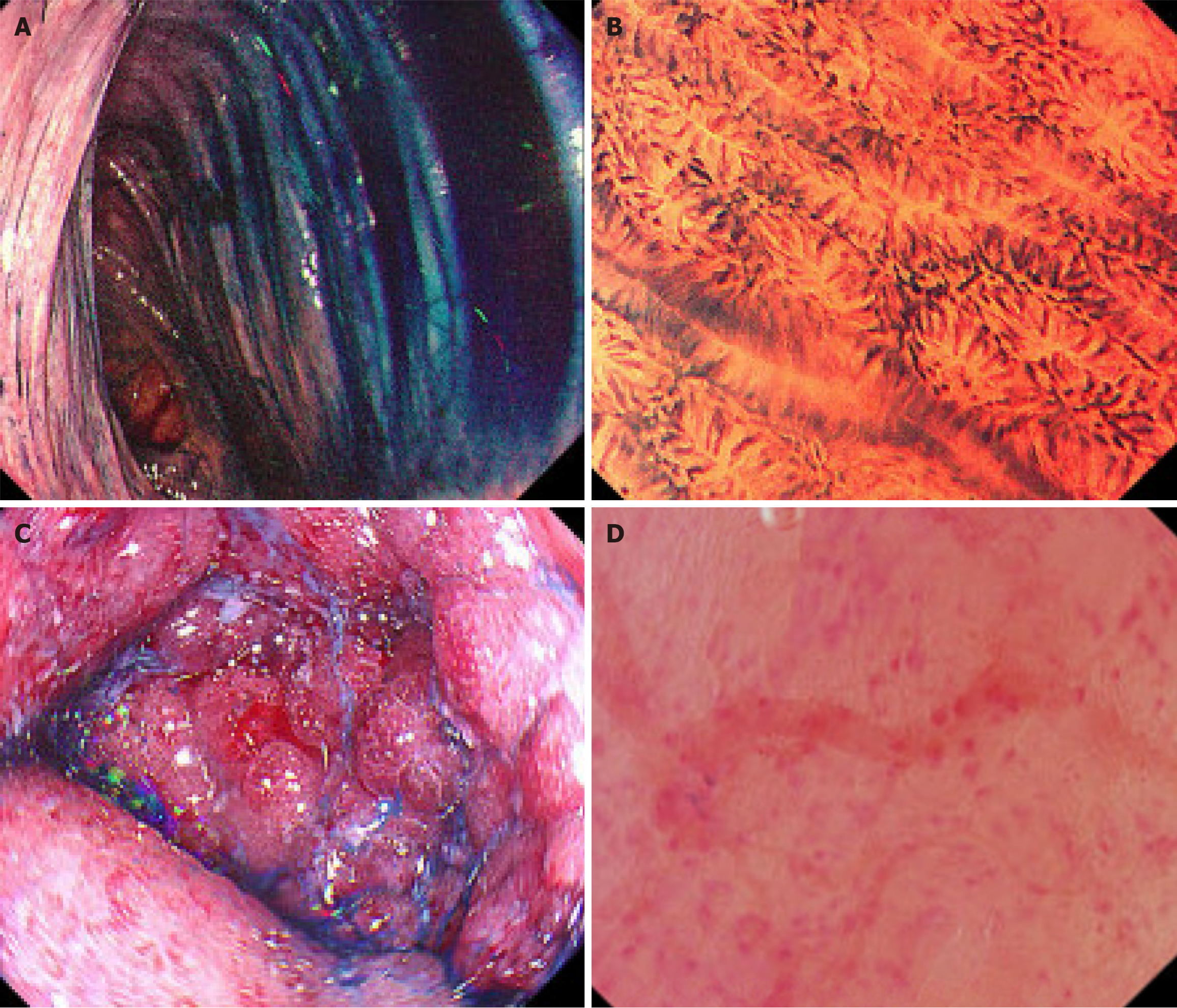

Colonoscopy was performed as per standard procedures, utilizing the endocytoscopy (CF-H290ECI, Olympus Medical Systems Corporation, Japan) at designated colonic segments based on the necessary clinical indications. Areas that were not adequately cleaned were irrigated with water until the mucosa was clearly visible. The mucosal surface was then assessed, and the MES was assigned to that segment, ranging from 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe disease activity[22]. Following this, 8-10 mL of 1% methylene blue, an approved staining dye for diagnostic procedures by the Therapeutic Goods Administration, was applied and irrigated to stain the colonic mucosa. After mucosa was stained, the endoscopic view was zoomed in, allowing for detailed assessment based on the ECSS. We evaluated only readable images that were well-stained, with over two-thirds of each image clearly visible. The ECSS, with a range of 0 to 6, evaluates three parameters: Crypt shape (0 to 3), crypt distance (0 to 2), and visible small vessels (0 to 1), where an ECSS of < 1 indicates remission[15]. The ELECT score, also ranging from 0 to 6, includes five parameters: Crypt shape (0 to 2), crypt distance (0 to 1), vascular architecture (0 to 1), inflammatory cell infiltrate (0 to 1), and the presence or absence of crypt abscess (0 to 1), with a score of < 2 indicating remission[19]. Examples of endoscopic pictures, MES, endocytoscopic, and NHI scores in this study are shown in Figure 1. Tissue biopsies were obtained from the stained area for subsequent histological assessment as part of the standard of care and were sent to the anatomical pathology department for analysis and scoring using the NHI. This typically involved taking two superficial biopsies from the lining of the colon. A maximum of two endocytoscopic assessments and tissue biopsies were permitted for each evaluated segment. All procedures were conducted by experienced IBD specialists and endoscopists to ensure accuracy. The pathologists were blinded to the endoscopy results to prevent any potential bias. We monitored potential side effects for four hours following the procedure, including assessing abdominal signs and any allergic reactions. Patient symptoms were tracked for a total of 24 hours post-procedure.

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD and median with interquartile range, while categorical variables were reported as frequency and percentage. The correlation between scores was assessed using Kappa (κ) statistics for categorical outcomes and Spearman’s rank correlation (r) for continuous outcomes. A P value of less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Diagnostic performance and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) were calculated to evaluate the diagnostic yield of ECSS and ELECT scores in predicting histological remission as defined by the NHI. All statistical analysis was conducted using Stata 17.0 (TX, United States).

A total of fifteen UC patients participated in this study, with a mean age of 41.3 ± 10.6 years, and 53.3% were male (Table 1). Of these, 11 patients (73.3%) were in clinical remission. A total of 61 of endocytoscopic evaluations were performed across large bowel segments. A total of 187 readable images were evaluated, with the mean number of readable images per segment as follows: Cecum 2.5, ascending colon 3.1, transverse colon 3.8, descending colon 3.0, sigmoid 2.8, and rectum 2.9 images. Biopsies were obtained at each evaluation. The most frequent assessed locations were sigmoid colon (24.6%), transverse colon (18%), and descending colon (18%), respectively. The majority had endoscopic remission with MES 0 (67.2%). The ECSS measured crypt shape, crypt distance, and small vessel visibility. Thirty-one assessment sites (50.8%) achieved ECSS remission. The ELECT measured crypt shape, crypt distance, vascular structure, inflammatory cell infiltrate, and crypt abscess, with 42 sites (68.9%) achieving ELECT remission. The percentage breakdown of parameters in each subscore is shown in Table 2. Biopsies from 39 sites (67.2%) had NHI of 0. Table 3 highlights the corresponding endoscopic remission rates and histological response/remission across each colonic seg

| Characteristics | Value |

| Male | 8 (53.3) |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 41.3 ± 10.6 |

| Clinical remission (partial Mayo score < 2) | 11 (73.3) |

| Assessment sites | 61 (100) |

| Cecum | 4 (6.6) |

| Ascending colon | 10 (16.4) |

| Transverse colon | 11 (18.0) |

| Descending colon | 11 (18.0) |

| Sigmoid | 15 (24.6) |

| Rectum | 10 (16.4) |

| Mayo endoscopic score | |

| 0 (endoscopic remission) | 41 (67.2) |

| 1 | 1 (1.6) |

| 2 | 13 (21.3) |

| 3 | 6 (9.8) |

| Endocytoscopy scores | |

| Endocytoscopy score (0-6), median (IQR) | 2 (0-4) |

| Crypt shape (0-3) | 1 (0-1) |

| Crypt distance (0-2) | 0 (0-1) |

| Small vessels (0-1) | 1 (0-1) |

| Endocytoscopy scores remission (< 1) | 31 (50.8) |

| ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis (0-6), median (IQR) | 1 (0-4) |

| Crypt shape (0-2) | 1 (0-1) |

| Crypt distance (0-1) | 0 (0-1) |

| Vascular architecture (0-1) | 0 (0-1) |

| Inflammatory cell infiltrate (0-1) | 0 (0-1) |

| Crypt abscess (0-1) | 0 (0-0) |

| ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis remission (< 2) | 42 (68.9) |

| Nancy histological index (0-4) | 0 (0-3) |

| 0 (histological remission) | 41 (67.2) |

| 1 | 3 (4.92) |

| 2 | 3 (4.92) |

| 3 | 8 (13.1) |

| 4 | 6 (9.84) |

| Endocytoscopy score | n (%) | ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis score | n (%) |

| Crypt shape | Crypt shape | ||

| Normal (0) | 28 (45.9) | Round/oval (0) | 31 (50.8) |

| Oval/possible distortion (1) | 19 (31.1) | Irregular, distorted (1) | 18 (29.5) |

| Irregular/severe distortion (2) | 7 (11.5) | Disruption/loss of crypts (2) | 12 (19.7) |

| Unclear/not recognized (3) | 7 (11.5) | Crypt distance | |

| Crypt distance | < 2 crypt diameter (0) | 44 (72.1) | |

| > 3 crypts in a visual field (0) | 7 (11.5) | > 2 crypt diameter (1) | 17 (27.9) |

| 2 < crypts < 3 in a visual field (1) | 43 (70.5) | Vascular architecture | |

| Elongated, < 2 crypts in a visual field (2) | 9 (14.8) | Normal: Round and small caliber (0) | 40 (65.6) |

| Small vessels | Distorted: Tortuous, dilated, erythrocyte leakage (1) | 21 (34.4) | |

| Not visible (0) | 22 (36.1) | Inflammatory cell infiltrate | |

| Visible (1) | 39 (63.9) | Absent (0) | 44 (72.1) |

| Present (1) | 17 (27.9) | ||

| Crypt abscess | |||

| Absent (0) | 61 (100) | ||

| Present (1) | 0 (0) |

| Endoscopic remission (MES = 0) | ECSS remission (< 1) | ELECT remission (< 2) | Histological response (NHI < 1) | Histological remission (NHI = 0) | |

| Cecum (n = 4) | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | 3 (75) | 3 (75) |

| Ascending colon (n = 9) | 9 (90) | 7 (70) | 9 (90) | 9 (90) | 9 (90) |

| Transverse colon (n = 12) | 9 (81.8) | 7 (63.6) | 9 (81.8) | 9 (81.8) | 7 (63.6) |

| Descending colon (n = 11) | 10 (90.9) | 6 (54.6) | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.9) | 10 (90.9) |

| Sigmoid (n = 15) | 8 (53.3) | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 9 (60) | 9 (60) |

| Rectum (n = 10) | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 4 (40) | 4 (40) | 3 (30) |

We assessed the relationship between the MES and ECSSs using r and κ indices, revealing a significantly strong corre

| Correlation | Spearman’s rho | P value | Kappa1 | P value |

| MES vs ECSS | 0.78 | < 0.001 | 0.60 | < 0.001 |

| MES vs ELECT score | 0.81 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | < 0.001 |

| ECSS vs NHI | 0.69 | < 0.001 | 0.47 | < 0.001 |

| ELECT vs NHI | 0.74 | < 0.001 | 0.88 | < 0.001 |

| ECSS vs NHI | ||||

| Cecum | 1.0 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Ascending colon | 0.59 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.05 |

| Transverse colon | 0.30 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.24 |

| Descending colon | 0.53 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.12 |

| Sigmoid | 0.87 | < 0.001 | 0.61 | 0.01 |

| Rectum | 0.90 | < 0.001 | 0.21 | 0.25 |

| ELECT vs NHI | ||||

| Cecum | 0.82 | < 0.001 | 1 | 0.02 |

| Ascending colon | 0.60 | 0.07 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Transverse colon | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.56 | 0.02 |

| Descending colon | 0.59 | 0.06 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Sigmoid | 0.91 | < 0.001 | 1 | < 0.001 |

| Rectum | 0.88 | < 0.001 | 0.78 | 0.005 |

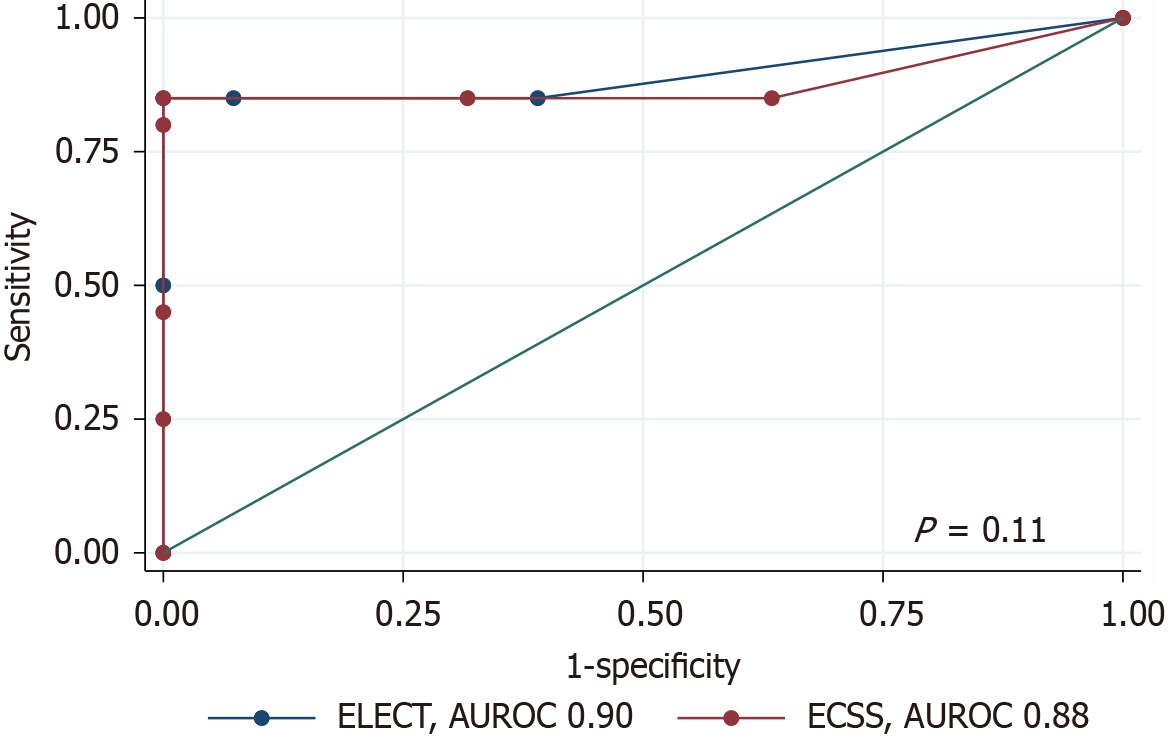

The diagnostic performance of ELECT in predicting histological remission had an AUROC of 0.90 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.78-1.00], compared to 0.88 (95%CI: 0.75-1.00) for ECSS. A DeLong test comparison showed no statistically significant difference between both scores (P = 0.11) (Figure 2). The ECSS, using a cut-off < 1 to indicate histological remission, demonstrated a sensitivity of 68.3% (95%CI: 51.9-81.9) and a specificity of 85.0% (95%CI: 62.1-96.8). In compa

In this study of UC patients, 61 endocytoscopies were conducted, with biopsies taken from various large bowel segments. Clinical remission was noted in 73.3% of patients, and 67.2% demonstrated endoscopic remission with MES 0. The remission rates for ECSS and ELECT were 50.8% and 68.9%, respectively. Histological remission, defined as NHI 0, was noted in 67.2% of assessment sites. Both ECSS and ELECT scores correlated strongly with the MES (r = 0.78 and r = 0.81, respectively) and the NHI (r = 0.69 and r = 0.74, respectively). Strong agreement was observed between ELECT remission and both endoscopic (κ = 0.88) and histological remission (κ = 0.88), whereas ECSS remission showed moderate agree

The ECSS initially focused on three structural parameters: Crypt shape, crypt distance, and small vessel visibility[15], while the ELECT expanded upon this by incorporating markers of active inflammation, including inflammatory cell infiltrates and crypt abscesses[19]. Following the establishment of the NHI, the most commonly used histological index for UC, which incorporates inflammatory cells as part of the scoring system[20], we hypothesized that the newer endocytoscopic scoring system may offer improved assessment of disease activity. The ELECT score is designed to be simpler, with the inclusion of more objective evaluation criteria. These additional parameters are expected to enhance the correlation and agreement with histological indices. As expected, strong correlations were observed between both ECSSs and the MES, with similar correlation values. However, the agreement for assessing endocytoscopic remission was lower when using the ECSS, possibly because the remission cut-off threshold for ECSS was set more strictly in the previous literature, defined as a score of < 1 out of 6. This stricter criterion may have contributed to the lower agreement observed compared to other scoring methods. While both ECSSs correlate well with the NHI, the ELECT score provides a more consistent and reliable assessment of histological remission. The higher κ value for ELECT may reflect its inclusion of additional inflammatory features, such as inflammatory cell infiltration, which likely improve its ability to capture subtle histological changes and align more closely with the NHI. In sub-analysis, the correlation between ECSSs and NHI varied across colonic segments. Strong correlations with statistical significance were observed in the sigmoid colon and rectum. In contrast, correlations in the ascending, transverse, and descending colon were weaker and did not reach statistical significance. This is likely due to variability in disease presentation and a limited number of samples, which may have reduced the statistical power of the analysis.

For diagnostic performance comparison, the AUROC for predicting histological remission was slightly higher for the ELECT score (0.90) compared to the ECSS (0.88), indicating a marginally better diagnostic accuracy for ELECT. However, a DeLong test showed no statistically significant difference between the scores (P = 0.11). The ELECT score demonstrated higher sensitivity than the ECSS, making it more effective at ruling out active disease when remission is indicated. The reduced sensitivity of the ECSS may also be due to its stricter remission cut-off (< 1), which could classify patients with minimal residual inflammation as having active disease.

The strengths of this study include its prospective design, which allows for the inclusion of a diverse range of clinical and endoscopic disease activities, making it as the first to compare the ELECT and ECSS scores. However, there are limitations to consider, such as a single-center study with a relatively small sample size that may affect the statistical power of the analyses. Additionally, the expertise of clinicians performing endocytoscopy could impact diagnostic. The unblinded design may also introduce bias, as it provided researchers with knowledge of patients’ clinical disease activity before assessment.

Endocytoscopy allows for real-time evaluation of both endoscopic and histological disease activity in UC and was found to be safe and well-tolerated. While both scoring systems have strong correlations to histological activity, the ELECT score demonstrates superior sensitivity and overall diagnostic accuracy compared to the ECSS for predicting histological remission, making it a valuable tool for real-time assessment of disease activity in UC. This ability could help improve clinical decision-making, precise treatment adjustments, and better long-term outcomes. Future studies should continue to explore the clinical implications of these findings in different and larger populations.

| 1. | Le Berre C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Danese S, Singh S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn's Disease Have Similar Burden and Goals for Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:14-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gros B, Kaplan GG. Ulcerative Colitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:951-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | de Souza HS, Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:13-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1185] [Cited by in RCA: 1190] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Schölmerich J, Bemelman W, Danese S, Mary JY, Rubin D, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Abreu MT, Dignass A; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 1982] [Article Influence: 396.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Yoon H, Jangi S, Dulai PS, Boland BS, Prokop LJ, Jairath V, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Singh S. Incremental Benefit of Achieving Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1262-1275.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park S, Abdi T, Gentry M, Laine L. Histological Disease Activity as a Predictor of Clinical Relapse Among Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:1692-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Christensen B, Hanauer SB, Erlich J, Kassim O, Gibson PR, Turner JR, Hart J, Rubin DT. Histologic Normalization Occurs in Ulcerative Colitis and Is Associated With Improved Clinical Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1557-1564.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099-105; quiz 1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 583] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta A, Yu A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ananthakrishnan AN. Treat to Target: The Role of Histologic Healing in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1800-1813.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shah SC, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Narula N. Mucosal Healing Is Associated With Improved Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1245-1255.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Iacucci M, Kiesslich R, Gui X, Panaccione R, Heatherington J, Akinola O, Ghosh S. Beyond white light: optical enhancement in conjunction with magnification colonoscopy for the assessment of mucosal healing in ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy. 2017;49:553-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Neumann H, Vieth M, Neurath MF, Atreya R. Endocytoscopy allows accurate in vivo differentiation of mucosal inflammatory cells in IBD: a pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:356-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Iacucci M, Jeffery L, Acharjee A, Nardone OM, Zardo D, Smith SCL, Bazarova A, Cannatelli R, Shivaji UN, Williams J, Gkoutos G, Ghosh S. Ultra-high Magnification Endocytoscopy and Molecular Markers for Defining Endoscopic and Histologic Remission in Ulcerative Colitis-An Exploratory Study to Define Deep Remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1719-1730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakazato Y, Naganuma M, Sugimoto S, Bessho R, Arai M, Kiyohara H, Ono K, Nanki K, Mutaguchi M, Mizuno S, Kobayashi T, Hosoe N, Shimoda M, Abe T, Inoue N, Ogata H, Iwao Y, Kanai T. Endocytoscopy can be used to assess histological healing in ulcerative colitis. Endoscopy. 2017;49:560-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bessho R, Kanai T, Hosoe N, Kobayashi T, Takayama T, Inoue N, Mukai M, Ogata H, Hibi T. Correlation between endocytoscopy and conventional histopathology in microstructural features of ulcerative colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:1197-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 16. | Nishiyama S, Oka S, Tanaka S, Sagami S, Nagai K, Ueno Y, Arihiro K, Chayama K. Clinical usefulness of endocytoscopy in the remission stage of ulcerative colitis: a pilot study. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1087-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Maeda Y, Ohtsuka K, Kudo SE, Wakamura K, Mori Y, Ogata N, Wada Y, Misawa M, Yamauchi A, Hayashi S, Kudo T, Hayashi T, Miyachi H, Yamamura F, Ishida F, Inoue H, Hamatani S. Endocytoscopic narrow-band imaging efficiency for evaluation of inflammatory activity in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:2108-2115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ueda N, Isomoto H, Ikebuchi Y, Kurumi H, Kawaguchi K, Yashima K, Ueki M, Matsushima K, Akashi T, Uehara R, Takeshima F, Hayashi T, Nakao K. Endocytoscopic classification can be predictive for relapse in ulcerative colitis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vitali F, Morgenstern N, Eckstein M, Atreya R, Waldner M, Hartmann A, Neurath MF, Rath T. Endocytoscopy for assessing histologic inflammation in ulcerative colitis: development and prospective validation of the ELECT (ErLangen Endocytoscopy in ColiTis) score (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:100-111.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mosli MH, Feagan BG, Zou G, Sandborn WJ, D'Haens G, Khanna R, Shackelton LM, Walker CW, Nelson S, Vandervoort MK, Frisbie V, Samaan MA, Jairath V, Driman DK, Geboes K, Valasek MA, Pai RK, Lauwers GY, Riddell R, Stitt LW, Levesque BG. Development and validation of a histological index for UC. Gut. 2017;66:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marchal-Bressenot A, Salleron J, Boulagnon-Rombi C, Bastien C, Cahn V, Cadiot G, Diebold MD, Danese S, Reinisch W, Schreiber S, Travis S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Development and validation of the Nancy histological index for UC. Gut. 2017;66:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized study. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1958] [Cited by in RCA: 2330] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/