Published online Jul 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.106352

Revised: April 18, 2025

Accepted: May 24, 2025

Published online: July 16, 2025

Processing time: 136 Days and 11.6 Hours

Foreign body (FB) ingestion is one of the most challenging clinical situations faced by endoscopists. Most esophageal FB impaction emergencies occur in children. It is important to study the epidemiological profile and endoscopic methods for treating FB impacted in the esophagus of children, as it can help in the deve

To define the profile of children seeking emergency care due to FB impaction in the esophagus, analyze factors associated with complications, and evaluate the effectiveness of rigid (RE) and flexible endoscopes (FE).

A retrospective cohort study of 166 children with impacted FB in the esophagus who underwent an endoscopy (FE = 84 vs RE = 82) at the Dr. José Frota Institute was performed. The primary outcomes were to assess the efficacy of the endoscopic technique and factors associated with complications. The secondary outcomes were age group, gender, symptoms, length of hospital stay, and location of the FB.

Boys (66.9%), preschoolers (43.4%), FB > 24 hours (62.7%), cervical esophagus (60.8%), coin ingestion (57.2%) and complaints of dysphagia (24.9%) and sialorrhea (23.1%) were the predominant findings. Endoscopy was successful (90.4%) with sedation (89.1%). A total of 97% of patients were discharged from the hospital, while 3% died. The average hospital stay length was 2.6 days. Most patients did not experience complications predominated (64.5%). Esophageal perforations were more frequent after RE (11% vs 4.8%), while FE was more effective (95.2% vs 85.4%). The χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables. For continuous variables, the Kruskal-Wallis test or analysis of variance was used. Statistical analyses were performed in R® software (version 1.3.1093).

Coins were the most frequent FBs and were mainly lodged in the upper esophagus of preschool boys. Risk factors for complications due to esophageal FB include battery ingestion, delayed removal (> 48 hours) and lodging in the thoracic esophagus. FE was generally more effective than RE for removing FBs; both procedures are safe.

Core Tip: The study described 166 cases of children with esophageal foreign body (FB) impaction, analyzed factors associated with complications, and evaluated the efficacy of rigid (RE) and flexible endoscopy (FE). Coins were the most common FB, and they were primarily lodged in the upper esophagus of preschool-aged children. Risk factors for complications include battery ingestion, delayed removal (> 48 hours), and lodging in the thoracic esophagus. Overall, FE was more effective than RE for FB removal, and both procedures are safe.

- Citation: Pereira LDM, Barreira MA, de Saboia Mont’Alverne TN, Maia MM, de Castro MAJ, de Oliveira JWC, Maia MM, de Vasconcelos PRC, de Oliveira AT. Endoscopic techniques and factors for complications in pediatric esophageal foreign body removal. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(7): 106352

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i7/106352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i7.106352

Foreign body (FB) ingestion is one of the most challenging clinical situations endoscopists face. Most FB ingestion emergencies occur in children, and the most frequent location is the esophagus (80%). Most pass spontaneously through the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) without complications. In other cases, endoscopic intervention is necessary[1]. Coins are the most common FB in children's upper GIT, while meatloaf is the most frequent in adults[2].

The choice of the most appropriate approach for treating FBs impacted in the esophagus varies widely between institutions. It depends on factors such as available resources, patient-related factors (age, clinical condition), type and size of the FB, anatomical site, time since ingestion, and the physicians' experience[3,4].

The risk of aspiration, obstruction, or perforation determines the timing of an endoscopy. The procedure should be performed on an emergency basis when patients have a complete esophageal obstruction and esophageal obstruction by batteries or sharp objects[4,5]. Most clinically stable patients without symptoms of upper GIT obstruction do not require an urgent endoscopy, as the object usually passes spontaneously. Esophageal coin impactions can be seen in asymptomatic patients but should be removed within 24 hours of ingestion if spontaneous passage does not occur[4].

A therapeutic endoscopy performed by an experienced and qualified endoscopist is a reliable, safe, and effective method for treating FB of the upper GIT. A variety of endoscopic techniques and instruments are indicated for different situations[5,6]. A rigid endoscope (RE) and flexible endoscope (FE) are both used to remove upper gastrointestinal FBs with high success rates and low morbidity[7]. Otorhinolaryngologists most commonly use the RE to remove FBs from the upper esophagus, while endoscopists usually use the FE to remove FBs in the lower esophagus[8].

Further understanding of the epidemiological profile and endoscopic methods for treating FBs impacted in the esophagus in children is important, as it can guide more effective, safer, and personalized preventive and therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, it can contribute to the efficiency of health services, reducing costs associated with complications and prolonged hospitalizations.

This study aimed to describe the profile of children who come to the emergency room due to FB impaction in the esophagus, analyze factors associated with complications, and evaluate the effectiveness of endoscopic techniques (FE vs RE). Evaluation included factors such as effectiveness in removing the FB, length of stay (LOS), complications and clinical outcome of the endoscopic procedures.

The retrospective cohort study was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board (number 6.886.384) and the Brazil platform system (approval with CAAE number 79007324.1.0000.5047). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and collected data from medical records.

Data was collected from the medical records of 166 patients aged 0 to 12 diagnosed with FB impacted in the esophagus. Patients were admitted to the pediatric emergency department of the Dr. José Frota Institute (IJF) from January 2018 to December 2023 and referred to the upper digestive endoscopy (UDE) service. The IJF is the largest trauma center in northeastern Brazil, located in Fortaleza-CE.

Patients aged over 12 with FB in the airways, lungs, and other parts of the GIT (pharynx, stomach, and intestines) were excluded from the study. Patients whose pediatrician opted for observation after clinical evaluation associated with imaging, patients with surgical indications on arrival at the emergency room, and patients where an UDE did not detect an FB were also excluded from the study. Patients were not followed up after hospital discharge.

Patients were treated according to the judgment and experience of the endoscopist with FE (n = 84) or RE (n = 82) for FB removal.

The primary outcomes aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of the endoscopic technique used and to compare FE and RE in removing FBs by evaluating the LOS, capacity for FB removal, complications, and clinical outcome. Prognostic factors associated with a higher risk of death were also assessed. The secondary outcomes were age group, gender, and symptoms, as well as the duration, location, and type of FB.

Endoscopy was performed under sedation or general anesthesia and used RE, FE, or both to remove esophageal FBs. The capacity for FB removal after the first UDE was classified as successful, unsuccessful, or FB pushed into the stomach. The LOS was recorded in days. Complications encountered during endoscopic intervention of the esophagus were mucosal edema or erosion and esophageal perforation. The need for an auxiliary surgical procedure was recorded. Clinical outcomes were divided into hospital discharge or death. The factors assessed with the highest risk of death were the type and outcome of the endoscopic procedure, complications, need for surgery, and the LOS. Factors associated with the development of complications due to FB were age group, LOS, location, nature, and type of FB.

The age range of the patients was divided into 0-4 years, 5-8 years, and 9-12 years. Gender was divided into male and female. The length of time the FB remained in the esophagus until UDE was performed was recorded as less than 24 hours, between 24 and 48 hours, and more than 48 hours. The location of the FB in the esophagus was divided into cervical, thoracic, and abdominal portions. The endoscopist recorded the type of FB after its removal. The symptoms recorded in the medical records by the emergency pediatrician were reported by the patient, companion, or family members.

All procedures were conducted by the endoscopist on duty with the assistance of an anesthesiologist who opted for sedation or general anesthesia. The routine of the IJF endoscopy service is to perform FB removal under sedation. The definitive airway is generally the option chosen when there is a greater chance of difficulty in extracting the FB, hemodynamic instability, greater risk of complications and/or bronchoaspiration.

The choice between FE and RE was based on the endoscopist's experience after evaluating the patient. Patients who developed suspected esophageal perforation, sepsis and hemodynamic instability after an endoscopic procedure underwent a surgical procedure.

Sample size calculation was performed considering a 95%CI and a 5% significance level (α = 0.05). To ensure the representativeness of the target population and the accuracy of the estimates, previous studies on the prevalence and characteristics of FB ingestion and aspiration in children were used as a reference. Based on these parameters and assuming an appropriate sampling error for robust statistical inferences, the minimum estimated sample size was 160 participants. This sample size provides sufficient statistical power to detect significant differences between the analyzed groups, minimizing biases related to sample variability. The sampling process followed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring that the collected data adequately represent the studied phenomenon. Thus, the results reliably reflect the occurrence and clinical characteristics of FB cases in children.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to analyze normality of continuous numerical variables. The data for continuous variables, such as age, were described using central tendency and dispersion measurements presented as medians and interquartile ranges, as well as means and standard deviations, depending on the data distribution. The results were expressed as absolute, relative, and percentage frequencies for categorical variables. Comparisons between categorical variables were made using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test, depending on whether they matched the expected frequencies. In some analyses of continuous variables, the residuals showed non-normal distributions; therefore, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons in the case of non-parametric distributions or analysis of variance in cases where normality was verified. All statistical analyses were performed using R® software (version 1.3.1093), thus guaranteeing the accuracy and reproducibility of the results.

There were a total of 166 patients, 111 (66.9%) were male and 55 (33.1%) were female. Concerning age, the highest number of patients (72; 43.4%) were between 0 and 4 years old. There were 57 (34.3%) cases in the 5 to 8 age group. The oldest age group in the study (9 to 12 years) had the lowest number of cases (37; 22.3%).

The time from the start of the FB to endoscopic procedure was less than 24 hours in 62 (37.3%) patients. Most patients (78/47.0%) took between 24 and 48 hours to have the UDE, while a minority (26/15.7%) waited more than 48 hours to perform the procedure. The cervical esophagus was the most common FB location, with 101 (60.8%) patients. The FB was found in the thoracic esophagus in 44 (26.5%) patients and in the abdominal esophagus in 21 (12.7%) patients. Most FBs were classified as inorganic (145/87.3%). The most frequent types of FB were coins (95/57.2%), batteries (32/19.3%), and food (20/12.0%) (Table 1).

| Variable | n = 169 |

| Impaction time (hours) | |

| < 24 | 62 (37.3) |

| 24-48 | 78 (47.0) |

| > 48 | 26 (15.7) |

| Location of the FB | |

| Cervical esophagus | 101 (60.8) |

| Thoracic esophagus | 44 (26.5) |

| Abdominal esophagus | 21 (12.7) |

| Nature of the FB | |

| Inorganic | 145 (87.3) |

| Organic | 21 (12.7) |

| FB type | |

| Coin | 95 (57.2) |

| Battery | 32 (19.3) |

| Food | 20 (12.0) |

| Non-rechargeable battery | 12 (7.2) |

| Bone | 6 (3.6) |

| Needle | 1 (0.6) |

Table 2 summarizes symptoms related to FB ingestion. The most common symptoms were dysphagia (42/24.9%), sialorrhea (39/23.1%), vomiting or regurgitation (28/16.6%), and chest or retrosternal pain (17/10.1%). Pain (23/13.6%) was often associated with more than one other symptom; 5 (3.0%) patients were asymptomatic.

| Symptom | n = 166 |

| Dysphagia | 42 (24.9) |

| Sialorrhea | 39 (23.1) |

| Vomiting/regurgitation | 28 (16.6) |

| Pain thoracic/retrosternal | 17 (10.1) |

| Abdominal pain | 9 (5.3) |

| Pain or cervical discomfort | 8 (4.7) |

| Irritability | 6 (3.6) |

| Asymptomatic | 5 (3.0) |

| Stuck | 3 (1.8) |

| Pain combined with other symptoms | 23 (13.6) |

Anesthesia data show 148 (89.1%) patients were sedated, while 18 (10.9%) patients received general anesthesia. During the endoscopy, 84 (50.6%) procedures used the FE and 82 (49.4%) used the RE. The endoscopic procedure successfully removed the FB in 150 cases (90.4%), while the first endoscopy was unsuccessful in 12 cases (7.2%). In four (2.4%) cases, it was necessary to push the FB into the stomach. Regarding outcome, 161 (97.0%) patients were discharged from hospital, while five (3.0%) patients died. The latter patients required a surgical procedure. The average LOS was 2.6 ± 3.0 days (mean ± SD) (Table 3).

| Variable | n = 166 |

| Anesthesia | |

| Sedation | 148 (89.1) |

| General | 18 (10.9) |

| Endoscopic technique | |

| Flexible | 84 (50.6) |

| Rigid | 82 (49.4) |

| Endoscopic procedure | |

| Successful | 150 (90.4) |

| Unsuccessful | 12 (7.2) |

| Pushed into the stomach | 4 (2.4) |

| Surgical procedure | |

| No | 164 (97.0) |

| Yes | 5 (3.0) |

| Clinical outcome | |

| Hospital discharge | 161 (97.0) |

| Death | 5 (3.0) |

| LOS (days) | |

| mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 3.0 |

Most patients (107/64.5%) had no complications related to the FB or the procedures. Mucosal erosion (26/15.7%) and mucosal edema (20/12.0%) were the most frequent complications, while esophageal perforations occurred in 13 (7.8%) patients.

There was no association between age and an increased or decreased risk of complications from esophageal FB. The factors associated with increased complications were the presence of a FB for over 48 hours, the presence of FB lodged in the thoracic esophagus, and the ingestion of batteries (P < 0.001). Furthermore, the factors associated with lower complication rates were the presence of an FB for less than 24 hours, the presence of an FB lodged in the cervical esophagus, and coin ingestion (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

| Variable | Complications | P value1 | |

| No, n = 107 | Yes, n = 59 | ||

| Impaction time (hours) | < 0.001 | ||

| < 24 | 47 (43.9) | 15 (25.4) | |

| 24-48 | 52 (48.6) | 26 (44.1) | |

| > 48 | 8 (7.5) | 18 (30.5) | |

| Location of the FB | < 0.001 | ||

| Cervical esophagus | 79 (73.8) | 22 (37.3) | |

| Thoracic esophagus | 16 (15.0) | 28 (47.5) | |

| Abdominal esophagus | 12 (11.2) | 9 (15.3) | |

| Nature of the FB | 0.003 | ||

| Inorganic | 99 (92.5) | 46 (78.0) | |

| Organic | 8 (7.5) | 13 (22.0) | |

| FB type | < 0.001 | ||

| Coin | 85 (79.4) | 10 (16.9) | |

| Battery | 9 (8.4) | 23 (39.0) | |

| Food | 8 (7.5) | 12 (20.3) | |

| Non-rechargeable battery | 4 (3.7) | 8 (13.6) | |

| Bone | 1 (0.9) | 5 (8.5) | |

| Needle | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.7) | |

There was no statistically significant difference between FE and RE complications (P = 0.413), but esophageal perforations occurred more frequently after RE procedures (11% vs 4.8%). Perforations were caused by battery (n = 11, 34.4%), needle (n = 1), and bone (n = 1) ingestion. Five (3.0%) patients required a surgical procedure, and they all died. Battery ingestion increased the risk of esophageal perforation, LOS, need for surgery, and risk of death (P < 0.001).

The need for surgery and the clinical outcome did not differ between RE and FE (P = 0.680). All fatal cases had ingested batteries more than 48 hours previously and were aged between 0 and 4 years. Four patients had a FB located in the thoracic esophagus, and one had a FB situated in the cervical esophagus. The other eight (4.7%) patients with perforations were successfully treated clinically; six had ingested batteries that were removed within the first 48 hours (n = 3, < 24 hours; n = 3, 24-48 hours).

In patients whose clinical outcome was death, RE was unsuccessful in three cases, and FE succeeded in the other two cases. Overall, FE was significantly more effective (P < 0.001) in removing FBs than RE (95.2% vs 85.4%). Unsuccessful procedures were only observed in the rigid method (12/14.6%); UDE had to be repeated in these cases. The RE was used to remove the FB from the thoracic esophagus 19 times and was unsuccessful in eight cases (42.1%). Patients who survived and had unsuccessful RE were hospitalized for between 3 and 18 days. However, there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.060) between the average LOS between the two procedures (FE 2.1 ± 1.8 vs RE 3.2 ± 3.7) (Table 5).

| Variable | Endoscopic procedure | P value1 | |

| Flexible, n = 84 | Rigid, n = 82 | ||

| Endoscopic procedure | < 0.001 | ||

| Successful | 80 (95.2) | 70 (85.4) | |

| Pushed into the stomach | 4 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unsuccessful | 0 (0.0) | 12 (14.6) | |

| Surgical procedure | 0.680 | ||

| No | 82 (97.6) | 79 (96.3) | |

| Yes | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Clinical outcome | 0.680 | ||

| Hospital discharge | 82 (97.6) | 79 (96.3) | |

| Death | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.7%) | |

| LOS (days) | 0.060 | ||

| mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 1.8 | 3.2 ± 3.7 | |

| Complications | 0.413 | ||

| Mucosal edema | 12 (14.3) | 8 (9.8) | |

| Mucosal erosion | 14 (16.7) | 12 (14.6) | |

| None | 54 (64.3) | 53 (64.6) | |

| Esophageal perforations | 4 (4.8) | 9 (11.0) | |

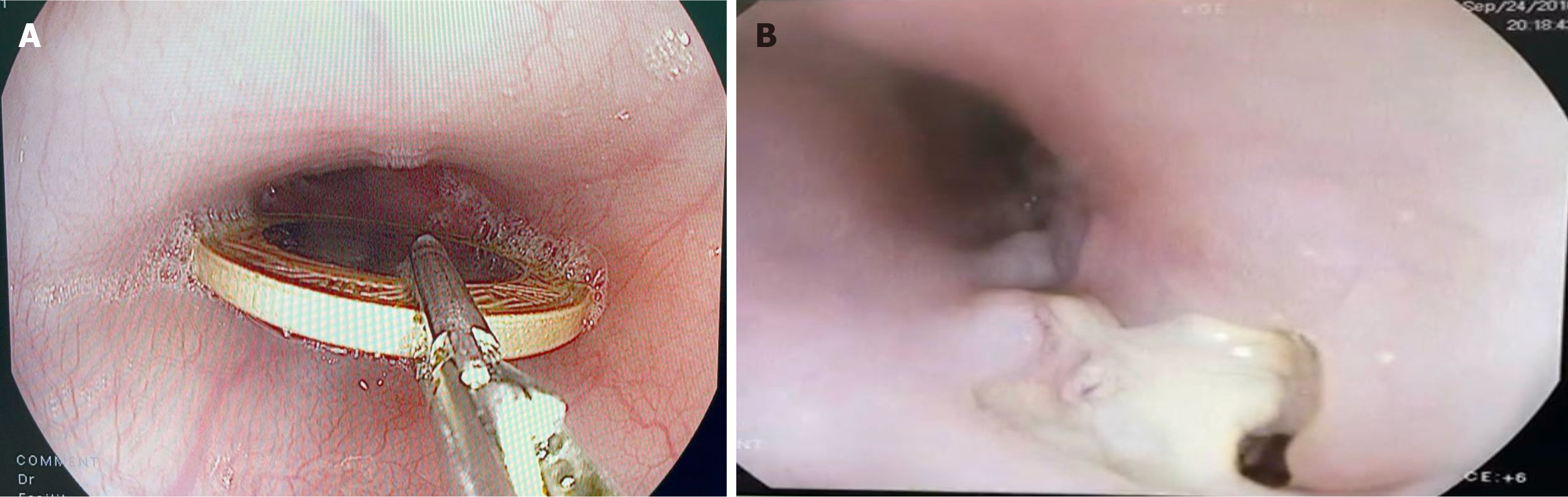

Figure 1A shows the successful extraction of a FB from the esophagus via FE. Figure 1B shows an area of fibrin and pus due to perforation of the cervical esophagus after battery ingestion 3 days prior.

There was no difference between the procedures (FE vs RE) regarding hospital discharge or death. Successful procedures were most frequent in patients who were discharged from the hospital, while unsuccessful procedures were more frequent in patients who died (P = 0.004). Patients who underwent surgery died, while patients who were discharged from the hospital did not undergo surgery (P < 0.001). The average LOS was longer in cases of death (3.6 ± 8.0 days) compared to cases of discharge (2.6 ± 2.7 days) (P = 0.017). As for complications, 66.5% of the discharged patients had no complications, while all the patients who died had complications (P < 0.001). Mucosal edema and erosion occurred exclusively in discharged cases (12.4% and 16.1%, respectively). Esophageal perforations were observed in all cases of death (100.0%) and in 5.0% of discharged cases (P < 0.001) (Table 6).

| Variable | Clinical outcome | P value1 | |

| High, n = 161 | Death, n = 5 | ||

| Endoscopic technique | 0.680 | ||

| Flexible | 82 (50.9) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Rigid | 79 (49.1) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Endoscopic procedure | 0.004 | ||

| Successful | 148 (91.9) | 2 (40.0) | |

| Pushed into the stomach | 4 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Unsuccessful | 9 (5.6) | 3 (60.0) | |

| Surgical procedure | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 161 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Yes | 0 (0.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

| LOS (days) | 0.017 | ||

| mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 2.7 | 3.6 ± 8.0 | |

| Complications | < 0.001 | ||

| Mucosal edema | 20 (12.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Mucosal erosion | 26 (16.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| None | 107 (66.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Esophageal perforations | 8 (5.0) | 5 (100.0) | |

Esophageal FBs are more frequently found in male preschool children. The most common FBs are coins, and FBs most frequently lodge in the upper third of the esophagus. The cricopharynx is the narrowest part of the upper digestive tract, and consequently, it is the most common region for esophageal obstruction by FBs[9-14]. These data are consistent with our study.

Studies involving large numbers of children report that a small percentage (< 2.0%) of ingested batteries became lodged in the esophagus[9,13,15]. However, Xu et al[14] published a study of 1355 Chinese children in which a sig

Most battery ingestions are harmless, although those that become lodged in the esophagus can cause severe injury. Button batteries associated with 20 mm lithium cells should be removed from the esophagus within 2 hours. Misdiagnosis and delay can lead to perforations, stenosis, fistulas, and death. The diameter of the battery (> 20 mm) associated with lithium cells, ingestion by children under four years of age, and delay in removing the FB are predictors of serious complications[16]. In the present study, we found that batteries lodged in the esophagus for more than 48 hours were associated with increased complications. Unfortunately, serious and fatal ingestion of batteries are increasing in frequency due to the rise of their use in household appliances; most deaths are related to late diagnosis[16,17].

Batteries create a local tissue pH environment of 10-13 and can induce liquefactive necrosis at the negative pole. This initial injury can progress with further tissue breakdown even after removal. Unfortunately, patients may present with vague symptoms like viral illnesses, and there is not always a known history of ingestion. Mitigation strategies with pre-removal use of honey and sucralfate and intraoperative use of acetic acid irrigation have been added to management guidelines aimed at neutralizing the pH and preventing tissue damage propagation[18].

The presence of symptoms is related to the location of the FB: esophageal FBs are more frequently associated with symptoms, while patients with gastric or intestinal foreign bodies are more frequently asymptomatic[19]. The most common symptoms associated with a FB lodging in the esophagus are sialorrhea, dysphagia, vomiting, and pain[9,14]. Some patients may be asymptomatic, while symptoms depend on the size, location, and nature of the FB[2]. Dysphagia (42/24.9%) and sialorrhea (39/23.1%) were the most common symptoms in this study. There were a few cases of asymptomatic patients (3.0%), which corroborates the need to perform endoscopic procedures quickly to avoid more serious complications.

Removal of esophageal FBs has low rates of esophageal perforation (< 2%) and death (< 1%)[9,13,20]. However, impaction of FBs for more than 24 hours is associated with a significant increase in the incidence of complications[1,5,21] and a lower endoscopic procedure success rate[21].

A study of 1355 children with FB impacted in the esophagus and a high rate of early endoscopies (83.7% < 24 hours) identified 23.3% (n = 130) of patients with complications. The most frequent were lesions (n = 31, 5.3%), ulceration (n = 13, 2.2%), and erosion of the esophageal mucosa (n = 86, 15.4%). Perforation occurred in 19 cases (3.4%). The risk factors that led to complications were young patients, a longer presence of the FB, battery ingestion, FB location in the upper esophagus, and fever or cough[14]. Geng et al[21] observed a high rate of complications (n = 646, 49.9%) in 1294 patients who ingested a FB, with esophageal perforations occurring in 49 patients (3.8%).

Ferrari et al[3] reviewed 1402 patients from five observational studies that used endoscopy to remove FBs. Complications occurred in 101 patients (7.2%), and the most frequent were mucosal erosion (26.7%), mucosal edema (18.8%) and esophageal perforations (10.9%). In this study, most patients (n = 104, 62.7%) underwent an endoscopy after more than 24 hours. Among the complications observed, mucosal erosion (26/15.4%) and mucosal edema (21/12.4%) were most frequent. Esophageal perforations occurred in 13 patients (7.8%), and there were five deaths (3.0%).

Romero et al[22] observed that whilst the most frequently ingested FB were coins, complications were more common in cases of battery ingestion and in those where diagnosis was made after 8 h. Patients with these risk factors could require more careful treatment and 1/6 patients (about 17%) developed some form of complication due to FB ingestion.

Once the decision of FB retrieval is made, appropriate endoscopic method, retraction tool, and anesthetic approach selection are important considerations of the procedures. A personalized approach to treating FB impaction is recommended. The choice of appropriate endoscopic ancillary device is essential for rapid and safe removal of the FB.

In the past, standard practice was to remove FBs under general anesthesia using RE. Advances in endoscopic equipment, accessories and technique have made significant advances in the last 50 years. Today, FE is the therapeutic modality of choice for most patients. The key principles for endoscopic management of esophageal FB are to protect the airway, maintain control of the object during extraction, and avoid causing additional damage[23].

FE has fewer complaints of post-procedure dysphagia, a reduced need for general anesthesia, shorter hospital stays[12,15], and serious complications[9]. It also allows for a better examination of the esophageal mucosa[12], is associated with lower costs, and is usually better tolerated[3].

RE with general anesthesia is often used in children due to the wider view, airway protection, and easy instrument manipulation[3,11,14,24]. Its use is more beneficial in children with sharp and large objects impacted in the upper esophagus[3,4,14], and respiratory symptoms[21]. In specific situations, it can remove blockages in the lower esophagus[3], although its use has a risk of esophageal perforation[11] and the procedure can take longer[12]. Ergun et al[25] strongly advocate for use of RE in the removal of sharp FBs and impacted food from the esophagus of children. RE allows the use optical forceps with a strong grasping ability for blunt and thick-edged FBs and to secure sharp and pointed objects inside the RE.

Complications can be minimized when RE is performed by experienced professionals[2], but endoscopists usually have less experience with this method. Sedation can also be used in selected cases[26]. Endotracheal intubation is more precisely indicated in younger children and those at higher risk for aspiration[23]. Although it is a less commonly used procedure, it can be advantageous in some circumstances[3]. Lee et al[27], showed the removal of 394 FBs from the GIT of children using sedation and most of the procedures (64.4%) were performed within 5 minutes.

At the IJF, the use of RE was not associated with the need for general anesthesia, and most endoscopic procedures (89.1%) were performed under sedation. Despite this, patients had an average hospital stay of more than 48 hours. Both methods are used by the endoscopy service with high efficacy and safety. The death rate (3.0%) may be related to a more unfavorable patient profile. Unsuccessful procedures were only observed with the rigid method, and FE should be preferred for removing FBs from the thoracic esophagus.

A study of 380 patients (52.63% children) showed a high rate of FBs in the upper esophagus (n = 303, 79.73%), and the use of RE under general anesthesia was effective at extracting impacted FBs. Notably, RE was also effective in extracting FBs from the middle esophagus (n = 61, 16.05%). Esophageal perforation occurred in two cases (0.5%)[2].

Gmeiner et al[8] compared the removal of FB from the esophagus with RE (n = 63) vs FE (n = 76). Removal of FBs was equally effective with both techniques (RE 95.2% vs FE 93.4%). No serious complications occurred with FE, while RE was associated with two esophageal ruptures requiring surgical intervention. Patient comfort was significantly different between the two procedures, as RE was always performed under general anesthesia and only a minority of patients undergoing FE required general anesthesia. In addition, 22 patients (29.0%) undergoing FE required hospital admission, while hospitalization was required in all patients undergoing RE performed under general anesthesia.

Both techniques successfully remove esophageal FBs, as evidenced by their high success rates and low complication rates[12,13,24,26]. As treatment failures have been managed with conversion to the other technique, both procedures should be included in the training curriculum[8,13]. However, some studies recommend FE as the first choice for esophageal FB extraction[8,12,28].

This study has limitations related to the retrospective nature of data collection. This may lead to the risk of bias because more complex cases were likely more frequently treated with a particular endoscopic technique. However, the fact that this is a study with only children with FBs from the esophagus contributes to a more homogeneous sample. Future studies may evaluate late complications (e.g., esophageal stricture) related to endoscopic extraction of FB from the esophagus.

Technological evolution may lead to a rise in battery intakes, but the related complications can be mitigated by reducing the size of these devices. Several types of batteries available on the market could be better detailed. The prevention of FB ingestion should focus on preschool children by raising public awareness of this problem.

Coins are the most frequent FBs and are mainly lodged in the upper esophagus of preschool boys. Dysphagia and sialorrhea are the most frequent symptoms, and there is a delay in the removal of FBs, as most are removed after 24 hours.

Risk factors for complications are battery ingestion, > 48 hours for removal, and lodging in the thoracic esophagus. Battery ingestion presented a higher risk of esophageal perforation, increased LOS, need for surgery, and risk of death. Esophageal perforations requiring surgery led to death.

Unsuccessful procedures were only observed with the rigid method, and FE should be prioritized for removing FBs from the thoracic esophagus. Both endoscopic techniques can be used to extract FB from the cervical esophagus, considering the surgeon's experience and FB characteristics. FE tended to reduce the LOS, and patients who died had a longer hospital stay. Therapeutic endoscopies (RE and FE) performed under sedation are effective and safe, in most cases.

We would like to thank the support and encouragement of the Hospital Geral de Fortaleza, the IJF and Dr. Roberto Ibiapina, who contributed to the completion of this study.

| 1. | Sugawa C, Ono H, Taleb M, Lucas CE. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:475-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wahid FI, Rehman HU, Khan IA. Management of foreign bodies of upper digestive tract. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferrari D, Aiolfi A, Bonitta G, Riva CG, Rausa E, Siboni S, Toti F, Bonavina L. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy in the management of esophageal foreign body impaction: systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Anderson MA, Appalaneni V, Banerjee S, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher LR, Fukami N, Harrison ME, Jain R, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Maple JT, Sharaf R, Strohmeyer L, Dominitz JA. Management of ingested foreign bodies and food impactions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1085-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Magalhães-Costa P, Carvalho L, Rodrigues JP, Túlio MA, Marques S, Carmo J, Bispo M, Chagas C. Endoscopic Management of Foreign Bodies in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract: An Evidence-Based Review Article. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2016;23:142-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chaudhary S, Khatri P, Shrestha S. Effectiveness of flexible endoscopy in the management of upper gastrointestinal tract foreign bodies at a tertiary hospital of western Nepal. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2020;10:3-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Chaves DM, Ishioka S, Félix VN, Sakai P, Gama-Rodrigues JJ. Removal of a foreign body from the upper gastrointestinal tract with a flexible endoscope: a prospective study. Endoscopy. 2004;36:887-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gmeiner D, von Rahden BH, Meco C, Hutter J, Oberascher G, Stein HJ. Flexible versus rigid endoscopy for treatment of foreign body impaction in the esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:2026-2029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Blanco-Rodríguez G, Teyssier-Morales G, Penchyna-Grub J, Madriñan-Rivas JE, Rivas-Rivera IA, Trujillo-Ponce de León A, Domingo-Porras J, Jaramillo-Alvarado JG, Cruz-Romero EV, Zurita-Cruz JN. Characteristics and outcomes of foreign body ingestion in children. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018;116:256-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ozguner IF, Buyukyavuz BI, Savas C, Yavuz MS, Okutan H. Clinical experience of removing aerodigestive tract foreign bodies with rigid endoscopy in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:671-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gilyoma JM, Chalya PL. Endoscopic procedures for removal of foreign bodies of the aerodigestive tract: The Bugando Medical Centre experience. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2011;11:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Popel J, El-Hakim H, El-Matary W. Esophageal foreign body extraction in children: flexible versus rigid endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:919-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Russell R, Lucas A, Johnson J, Yannam G, Griffin R, Beierle E, Anderson S, Chen M, Harmon C. Extraction of esophageal foreign bodies in children: rigid versus flexible endoscopy. Pediatr Surg Int. 2014;30:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu G, Chen YC, Chen J, Jia DS, Wu ZB, Li L. Management of oesophageal foreign bodies in children: a 10-year retrospective analysis from a tertiary care center. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cheng W, Tam PK. Foreign-body ingestion in children: experience with 1,265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1472-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC, Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1168-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kurowski JA, Kay M. Caustic Ingestions and Foreign Bodies Ingestions in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64:507-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sethia R, Gibbs H, Jacobs IN, Reilly JS, Rhoades K, Jatana KR. Current management of button battery injuries. Laryngoscope Investig Otolaryngol. 2021;6:549-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gatto A, Capossela L, Ferretti S, Orlandi M, Pansini V, Curatola A, Chiaretti A. Foreign Body Ingestion in Children: Epidemiological, Clinical Features and Outcome in a Third Level Emergency Department. Children (Basel). 2021;8:1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hariga I, Khamassi K, Zribi S, Amor MB, Gamra OB, Mbarek C, Khedim AE. Management of foreign bodies in the aerodigestive tract. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;66:220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Geng C, Li X, Luo R, Cai L, Lei X, Wang C. Endoscopic management of foreign bodies in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a retrospective study of 1294 cases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:1286-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Romero BM, Vilchez-Bravo S, Hernández-Arriaga G, Bueso-Pineda L, Franchi T, Tovani-Palone MR, Mejia CR. Factors associated with complications of foreign body ingestion and/or aspiration in children from a Peruvian hospital. Heliyon. 2023;9:e13450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Poddar U, Samanta A. Foreign Body Ingestion in Children: The Menace Continues. Indian Pediatr. 2022;59:716-717. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Tseng CC, Hsiao TY, Hsu WC. Comparison of rigid and flexible endoscopy for removing esophageal foreign bodies in an emergency. J Formos Med Assoc. 2016;115:639-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ergun E, Ates U, Gollu G, Bahadir K, Yagmurlu A, Cakmak M, Aktug T, Dindar H, Bingol-Kologlu M. An algorithm for retrieval tools in foreign body ingestion and food impaction in children. Dis Esophagus. 2021;34:doaa051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Emara MH, Darwiesh EM, Refaey MM, Galal SM. Endoscopic removal of foreign bodies from the upper gastrointestinal tract: 5-year experience. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2014;7:249-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Lee YJ, Lee JH, Park KY, Park JS, Park JH, Lim TJ, Myong JP, Chung JH, Seo JH. Clinical Experiences and Selection of Accessory Devices for Pediatric Endoscopic Foreign Body Removal: A Retrospective Multicenter Study in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38:e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jayachandra S, Eslick GD. A systematic review of paediatric foreign body ingestion: presentation, complications, and management. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |