Published online Apr 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i4.101998

Revised: January 21, 2025

Accepted: March 13, 2025

Published online: April 16, 2025

Processing time: 191 Days and 18.2 Hours

This is a randomized study to compare the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions obtained with the 22-gauge Franseen (EUS-fine needle biopsy) vs the 22-gauge standard needle (EUS-fine needle aspiration) without rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE), since, in most endoscopy units around the world ROSE is not routinely available.

To investigate the accuracy of EUS-guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions obtained between two different needles without ROSE.

Patients with a solid pancreatic were included. Patients were biopsied in a randomized order. The primary endpoint was the diagnostic sensitivity for pancreatic malignancy (PM). Secondary outcomes were adequacy of the sample, the mean tissue area, the mean tumor area, and the adverse event rate.

The final diagnosis was pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 38 (76%), neuroendocrine tumor in 4 (8%), chronic pancreatitis in 3 (6%) patients. The sensitivity for PM with Franseen needle was 0.91 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.80-0.98], vs 0.8 (95%CI: 0.67-0.91) (P = 0.025) with standard needle. The specificity for PM did not differentiate. The accuracy of the standard needle for PM was 0.80 (95%CI: 0.66-0.90), and the Franseen group was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.78-0.97) (P = 0.074). The technical success rates for the standard and Franseen needle groups were 94% (95%CI: 0.83-0.99) and 100% (95%CI: 0.92-1.00), respectively. The mean total tissue area in mm2 (SD) was greater in the Franseen group, 2.07 (0.22) vs 1.16 (0.17) (P < 0.01). The mean tumor area in mm2 (SD) was not different in Franseen group vs standard group, 0.42 (0.09) vs 0.47 (0.09) (P = 0.80). There were no adverse events.

The sensitivity for PM and mean total tissue area, was greater in the as compared with standard needle. The mean tumor area did not differ between the groups.

Core Tip: The main of the study was based in assess the sensitivity of endoscopic ultrasound needles for diagnosing pancreatic malignancy. We found that the diagnostic sensitivity for pancreatic malignancy as well as the mean total tissue area collected was greater with the Franseen needle group compared with the standard needle group. Taking into account, the procedure was done in the absence of an onsite site pathologist for evaluation of the sample collected, bringing important contribution to institutions that do not have pathologist in the examination room.

- Citation: Paduani GF, Felipe LM, De Paulo GA, Lenz L, Martins BC, Matuguma SE, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, De Mello ES, Maluf-Filho F. Prospective randomized study comparing Franseen 22-gauge vs standard 22-gauge needle for endoscopic ultrasound guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(4): 101998

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i4/101998.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i4.101998

Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) was initially introduced in the early 1990s and was quickly recognized as the most efficient technique for sampling pancreatic lesions[1].

The use of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles for solid pancreatic lesions has a sensitivity ranging from 64% to 95%, a specificity ranging from 75% to 100%, and a diagnostic accuracy ranging from 78% to 95%[2,3].

Several strategies have been used to enhance the diagnostic yield of EUS-FNA, such as larger gauge needles[4], rapid onsite evaluation (ROSE)[5], implementation of suction[6], slow withdrawal of the stylet[7], wet suction[8], macroscopic onsite assessment of the material (MOSE)[9], and even the detection of KRAS mutation in the aspirate[10].

The ROSE involves the immediate analysis of the material by the cytopathologist or a cyto technician to guarantee the quality of the aspirated material and even perform a preliminary diagnosis. There is evidence that evaluation at the puncture site by the pathologist increases the diagnostic yield[11], particularly in difficult cases such as lymphoma and association of malignancy with chronic pancreatitis. In a study with 230 patients, the investigators concluded that, in the absence of ROSE, the probability of inconclusive results increased by more than twice (P = 0.03) and by 3 times the number of inappropriate samples for evaluation in block (P < 0.001)[12]. However, availability, logistics, and costs are relevant limitations for the implementation of ROSE in EUS-FNA routine.

Recently, the Franseen needle was designed to obtain samples that allow histological rather than cytological analysis. The puncture performed with these needles has been called endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB). The Franseen needle features a crown tip, with three symmetrical surfaces that exhibit three cutting edges. This geometry contributes to a long insertion length and crown tip area that aids better tissue acquisition.

In a pilot study with 30 patients, in which EUS-FNB samples were obtained from pancreatic lesions or other solid masses using Franseen needles, adequate samples with diagnostic capacity were confirmed onsite by the pathologist in 96% of patients, with histological diagnoses by cell block in 96.6% of patients[13]. It is possible that the triple cutting edge could provide more tissue volume than the standard 22-gauge needle.

Some randomized clinical trials (RCT) studies have compared 22-gauge FNB and standard needles for solid pancreatic lesions[14-18]. In the majority of them, ROSE was available.

The objective of this study was to compare the diagnostic accuracy of Franseen 22-gauge needle vs standard 22-gauge needle for EUS-guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions without ROSE. In most endoscopy units around the world ROSE is not routinely available.

This was a randomized study conducted at the Instituto do Cancer do Estado de Sao Paulo between December 2019 and January 2023 (registration number at clinicaltrials.gov: NCT04877340). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board (No. 26962419.3.0000.0065).

Patients with suspected solid pancreatic lesions larger than 15 mm, identified by tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, referred for EUS-guided sampling were eligible for inclusion. Patients willing to participate provided a written informed consent. Patients were submitted to a minimum of two passes with the standard needle and two passes with the Franseen needle. The order of the use of the needles was randomized using permutation blocks.

A function was created with MS Excel, with randomization between blocks of 6, 8, and 10, generating a sequential list of 50 numbers, between 1 and 2 (each number representing a needle type). Randomization process used sealed and sequentially numbered envelopes. Patients were excluded if they had cystic lesions or abnormal coagulation parameters (international normalized ratio > 1.5, platelet count < 50000 cells/mm3).

The primary endpoint was the diagnostic accuracy for the pancreatic malignancy (PM) (pancreatic adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumor, metastatic lesion). Secondary endpoints were adequacy of the sample (technical success rate), the mean tissue area, the mean tumor area, and the adverse event rate.

Pancreatitis (defined as abdominal pain associated with a 3× elevation of serum amylase or lipase), and bleeding (defined as haematemesis or melaena requiring blood transfusion or endoscopic or radiological intervention), occurring within the first 7 days after the endoscopic procedure were considered as adverse events. In the period of 7 days after the procedure, the patients were contacted by phone call in order to evaluate any related adverse event.

The procedures were performed using a linear echoendoscope (UCT180; Olympus America Corp, Centre Valley, Pa), in propofol-sedated patients, positioned in left lateral decubitus.

The pancreatic mass was firstly punctured with a needle determined by randomization, followed by the other needle in the sequence. Four endoscopists, all with more than 1500 echoendoscopy exams, and fellows under their supervision performed the procedures.

With the first randomized needle, we performed two passes-the first with a slow pull and the second with a 20cc syringe aspiration. Each pass had at least 20 back-and-forth movements. Then, we performed two more passes with the second needle, also using the slow pull and 20cc syringe aspiration sequence. This means that a minimum of four needle passes were performed in all patients. Additional punctures, with both needles, were performed at the discretion of the operator if he or she judged that the material was insufficient. This evaluation was not considered MOSE because we did not evaluate the specimen under a magnifying lens.

Part of the specimen from each pass was smeared onto three slides, and the remaining material was immersed in a formaldehyde solution for cell block analysis.

Specimens were collected for cell block in a methanol-based preservative solution which was subsequently centrifuged, decanted, and combined to form a tissue clot. After forming a tissue clot, specimens were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained using haematoxylin and eosin for histological interpretation. The block was scanned and Panoramic Viewer 1.15.3 (3DHISTECH) was used to photograph the block cuts, always with a measurement reference ruler.

The areas in the photo fields were measured using ImageJ 1.53k (National Institutes of Health, United States; public domain), always calibrating the scale immediately after each photo, and then measuring the non-tumor areas (fibrosis, non-neoplastic pancreas, non-neoplastic intestinal wall tissue, or any other non-neoplastic pathway tissue) and tumor areas. Areas of necrosis, haemorrhage and mucus were not considered as tissue.

Possible histological findings were classified as positive for malignancy, suspicious for malignancy, negative for malig

Diagnosis accuracy was defined as a correct diagnosis provided by the needle specimen. The definitive diagnosis of malignancy was based on surgical or clinical assessment (e.g. histology of a surgically resected specimen, or histology of a biopsy of a distant metastasis associated with a clinical course compatible with malignant disease). The definitive diagnosis of benign disease was based on benign histology findings associated with a clinical course compatible with benign disease. The minimum follow-up duration was established as 6 months.

Technical success rate was defined as the presence of samples adequate for cytology or histology. When neither the smears nor the cell-blocks samples allowed a diagnosis, this situation was considered as insufficient material for analysis, and a technical failure.

In the presence of malignancy in the tissue sample, the proportion of the positive area for malignancy was calculated and divided by the total area of the sample. This calculation was performed for specimens obtained from both needles.

Diagnostic sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for malignancy were calculated for both needles. Truly positive cases for malignancy were considered based on the association of imaging findings, clinical evolution and histology (see above). True negative cases for malignancy were considered when the association of histology findings, imaging and clinical evolution were inconsistent with malignancy after a minimum follow up of 6 months.

All the specimens were analysed by a senior pathologist who was masked to the type of needle that was used.

In our center, the historical diagnostic accuracy for EUS-FNA for solid pancreatic masses using standard 22-gauge needles prior to this study was 75% (unpublished data). This is a superiority trial, where we hypothesised an increase in diagnostic yield of 25% with the use of the Franseen needle compared to standard needles (75%-95%). Adopting a statistical power of 80% and a P alpha level of 5%, 98 patients should be included. Considering that both needles will be used in all patients, 49 patients would be sufficient. Adopting a loss rate of 10%, we estimated the inclusion of 54 patients. Continuous variables were described as means and SD or medians and interquartile range. The analysis was carried out in two stages. The first stage consisted of calculating descriptive statistics of the variables of interest. The second step, in calculating the comparisons of prediction metrics. The prediction metrics evaluated were sensitivity, specificity, positive value prediction and negative value prediction. For to carry out these comparisons, the McNemar tests were used, for sensitivity and specificity, and the Moskowitz and Pepe test, for prediction of positive value and prediction of negative value. All of these analyzes were performed with the DTComPair package of the R language.

From December 2019 and January 2023, we screened and included 50 consecutive patients with solid pancreatic lesions referred to EUS-guided sampling. There was no screen failures.

The mean age of the study cohort was 64 years (range 36-88 years), and 24 patients (48%) were male. The mean size of the pancreatic mass was 3.47 cm (range 1.7 cm-7.0 cm). Most lesions were located in the pancreatic head (62%) or uncinate process (12%). Vascular invasion was observed in 64% of patients (Table 1). The pathological analysis diagnosis was pancreatic adenocarcinoma in 74%, neuroendocrine tumor in 8 % and chronic pancreatitis in 6% (Table 2).

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| mean age | 64.1 |

| Range | (36-88) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 26 |

| Male | 24 |

| Mean pancreatic mass size (cm) | |

| Mean | 3.47 |

| Range | 1.7-7.0 |

| Pancreatic mass location | |

| Head | 31 (62) |

| Uncinate | 6 (12) |

| Neck | 6 (12) |

| Body | 5 (10) |

| Tail | 2 (4) |

| Vascular invasion | 32 (64) |

| Venous vascular invasion | |

| Portal vein | 16 (51.6) |

| Superior mesenteric vein | 19 (61.3) |

| Splenic vein | 13 (41.9) |

| Definitive diagnosis (n = 50) | Standard needle (n = 50) | Franseen needle (n = 50) | ||

| Adenocarcinoma/pancreatic cancer (n = 38) | n = 31 | n = 35 | ||

| Benign lesion | Chronic pancreatitis (n = 3) | Benign lesion | Chronic pancreatitis (n = 2) | |

| Mucinous neoplasia (n = 1) | Mucinous neoplasia (n = 1) | |||

| Inconclusive (n = 3) | Inconclusive (n = 0) | |||

| Neuroendocrine tumor | n = 4 | n = 4 | ||

| Metastasis | n = 2 | n = 2 | ||

| Lymphoma | Chromic pancreatitis (n = 1); Lymphoma (n = 0) | Chronic pancreatitis (n = 1); Lymphoma (n = 0) | ||

| Plasmocitoma | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| Solid pseudopapillary tumor | n = 1 | n = 1 | ||

| Chronic pancreatitis | n = 3 | n = 3 | ||

Final diagnoses were based on histological examination. No additional passes were necessary. In one case, the diagnosis was established by immunohistochemistry (as a B-cell lymphoma). The sensitivity for a final diagnosis of PM was significantly greater in the Franseen group 0.91 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.80-0.98] vs standard group 0.81 (95%CI: 0.67-0.91) (P = 0.025). The specificity was 0.67 (95%CI: 0.09-0.99) for PM in the standard and 0.67 (95%CI: 0.09-0.99) for the Franseen needle groups, without difference between the groups. The accuracy of the standard needle for PM was 0.80 (95%CI: 0.66-0.90). In the Franseen needle group, accuracy for PM was 0.90 (95%CI: 0.78-0.97) (P = 0.074). The positive predictive value for the standard group for PM was 0.97 (95%CI: 0.87-1.00) and for the Franseen group, 0.98 (95%CI: 0.88-1.00), (P = 0.36). The negative predictive value for PM in the standard needle group was 0.18 (95%CI: 0.02-0.52), compared to 0.33 (95%CI: 0.04-0.78) in the Franseen needle group, with P = 0.028 (Tables 3, 4 and 5). Although this study only enrolled patients with solid lesions, one patient was diagnosed with an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. This patient had a solid tumor on both computed tomography scan and EUS imaging.

| Diagnostic method | Disease | ||

| Pancreatic malignancy1 (n = 47) | Chronic pancreatis (n = 3) | Total | |

| Positive for malignancy | 38 | 1 | 39 |

| Negative for malignancy | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Total | 47 | 3 | 50 |

| 95%CI | |||

| Sensitivity | 0.81 (0.67-0.91) | ||

| Specificity | 0.67 (0.09-0.99) | ||

| PPV | 0.97 (0.87-1.00) | ||

| NPV | 0.18 (0.02-0.52) | ||

| Accuracy | 0.80 (0.66-0.90) | ||

| Diagnostic method | Disease | ||

| Pancreatic malignancy1 (n = 47) | Chronic pancreatis (n = 3) | Total | |

| Positive for malignancy | 43 | 1 | 44 |

| Negative for malignancy | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Total | 47 | 3 | 50 |

| 95%CI | |||

| Sensitivity | 0.91 (0.83-0.98) | ||

| Specificity | 0.67 (0.09-0.98) | ||

| PPV | 0.98 (0.88-1.00) | ||

| NPV | 0.33 (0.04-0.78) | ||

| Accuracy | 0.90 (0.78-0.97) | ||

| Metrics | FNA | FNB | Statistical difference | P value1 |

| Sensitivity | 0.809 | 0.915 | 5.000 | 0.025 |

| Specificity | 0.667 | 0.667 | - | - |

| PPV | 0.974 | 0.977 | 0.913 | 0.361 |

| NPV | 0.182 | 0.333 | 2.202 | 0.028 |

| Accuracy | 0.800 | 0.900 | 3.200 | 0.074 |

The technical success rates for standard and Franseen needle groups were 94% (95%CI: 0.83-0.99) and 100% (95%CI: 0.92-1.00), respectively.

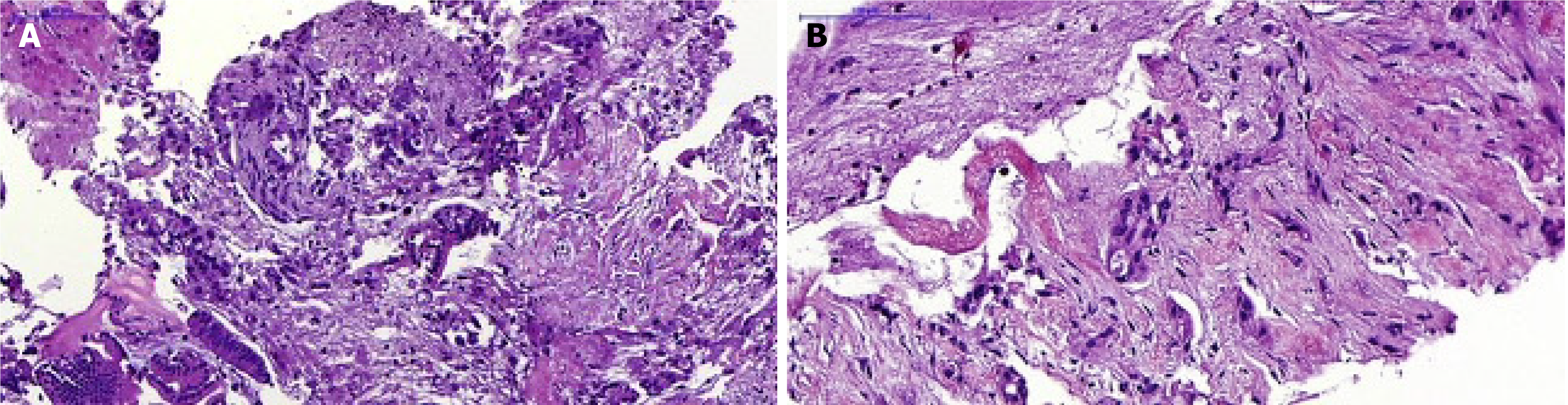

The mean total tissue area mm2 (± SD) was significantly higher for the Franseen than for the standard needle group, 2.07 ± 0.22 vs 1.16 ± 0.17 (P < 001). The mean total tumor area, mm2 (± SD) did not differ between the Franseen, and in the standard needle groups 0.42 ± 0.09 vs 0.47 ± 0.09, P = 0.8 (Table 6). In Figure 1, there are examples of pathology images from samples obtained with the standard and Franseen needles, respectively.

| Standard needle | Franseen needle | P value | |

| Mean total tissue area, mm2 (SD) | 1.16 (0.17) | 2.07 (0.22) | 0.001 |

| Median | 0.45 | 1.09 | |

| 75% IQR | 1.53 | 2.89 | |

| Range | 0-9.76 | 0-9.22 | |

| Mean total tumor area, mm2 (SD) | 0.42 (0.09) | 0.47 (0.09) | 0.8 |

| Median | 0.05 | 0.05 | |

| 75% IQR | 0.51 | 0.50 | |

| Range | 0-7.03 | 0-4.88 |

In this study, we observed mild abdominal pain in only 5 patients, that resolved with simple analgesia and did not required hospitalization, three in the FNA and two in the FNB group. There were no cases of pancreatitis or bleeding related to the procedure.

We conducted a randomized study to compare the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-guided sampling of pancreatic solid lesions obtained with the 22-gauge Franseen vs the 22-gauge standard needle with no ROSE. The justification of the study design relies on the fact that ROSE is not routinely available in many centers in our country and around the world.

Our findings suggest a better diagnostic performance with the Franseen needle translated in a better sensitivity and negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PM. In fact, with the Franseen needle it was possible to correctly diagnose pancreatic adenocarcinoma in four misdiagnosed patients (inconclusive diagnosis in three and chronic pancreatitis in one patient) with the standard needle. The technical success rates for the standard and Franseen needle groups were 94% (95%CI: 0.83-0.99) and 100% (95%CI: 0.92-1.00) respectively, which reflects the greater amount of tissue samples obtained by the Franseen needle (mean total tissue area in mm2, standard vs Franseen needles, 1.16 vs 2.07, P = 0.001). Recently, Kovacevic et al[19] also used a Franseen needle (TopGain; Medi-Globe GmbH, Grassau, Germany), as in our study, and found a larger area of tissue with the FNB vs the FNA needle (2.74 mm2vs 0.44 mm2, P < 0.001).

Facciorusso et al[20], in a network meta-analysis, observed no significant difference in diagnostic accuracy between EUS-guided tissue acquisition for sampling pancreatic masses using different needle models. However, this systematic review was based mainly on studies that used first-generation reverse-bevel FNB needles because only a limited number of RCTs that tested newer end-cutting FNB needles were available at that time.

We found five RCTs comparing FNA vs FNB needles. Their results are summarized in Table 7.

| Ref. | FNA (n) | FNB (n) | ROSE | Randomization | Technique of sampling | Sensitivity for malignancy (95%CI)-FNA | Sensitivity for malignancy (95%CI)-FNB | P value | Accuracy malignancy (95%CI)-FNA | Accuracy malignancy (95%CI)-FNB | P value |

| Bang et al[14] | 22-gauge (28) | Reverse bevel (28) | Yes | Sequence of the needle | Capillarity and dry suction | 100 | 83.3 | 0.26 | |||

| Bang et al[15] | 22-gauge (46) | Franseen 22-gauge (46) | Yes | Sequence of the needle | 82.6 | 97.8 | 0.03 | ||||

| Noh et al[16] | 22-gauge (30) | Reverse bevel 22-gauge (30) | Yes | Sequence of the needle | Dry suction | 95 | 93.3 | 0.564 | |||

| Vanbiervliet et al[17] | 22-gauge (39) | Reverse bevel 22-gauge (41) | Yes | First needle FNA | Dry suction | 92.5 | 90 | 0.68 | |||

| Mavrogenis et al[18] | 22-gauge (19) | Reverse bevel 25-gauge (19) | No | Sequence of the needle | Capillarity and dry suction | 89.5 (66.82-98.39) | 89.5 (66.82-98.39) | 84.8 (67.3-94.2) | 84.8 (67.3-94.2) | ||

| Kovacevic et al[19] | 22-gauge (33) | 22-gauge (31) | No | Sequence of the needle | Capillarity | 65.5% | 89.7% | > 0.5 | 69.7 (51.3-84.4) | 90.3 (74.2-98%) | |

| Our study | 22-gauge (50) | Franseen 22-gauge (50) | No | Sequence of the needle | Capillarity and dry suction | 0.83 (0.69-0.92) | 0.91 (0.80-0.98) | 0.84 (0.71-0.93) | 0.92 (0.81-0.98) |

In a more recent network meta-analysis of different FNB needles, Gkolfakis et al[21] found that Franseen and fork-tip needles, particularly those of 22-gauge size, showed the highest performance for tissue acquisition. One observation was that the availability of ROSE had a great impact on the comparative efficacy of different techniques for tissue sampling of pancreas.

In a retrospective study, Wong et al[22] found that the diagnostic yield of solid pancreatic mass was higher with FNB using the Franseen needle than in FNA using the conventional FNA needle in a center where ROSE was unavailable[22]. Therefore, it seems that a main advantage of EUS-FNB needles, particularly with newer end-cutting needles, is to obviate the use of ROSE by performing the EUS-FNB sampling without an on-site pathologist[16]. Our findings are in line with this concept.

In times of personalised medicine, molecular profiling of pancreatic cancer and application of next-generation sequencing may provide an opportunity to advance the development of targeted therapies. Asokkumar et al[23] demonstrated that the Franseen EUS-FNB device can obtain better nucleic acid yield than EUS-FNA, with quality and quantity sufficient for downstream genomics applications. Therefore, the FNB can become a convenient and safe method for obtaining tumor material for precision genomics. This could have implications for the outcome of pancreatic cancer treatment in the near future.

There are a few limitations of this study. First, we included only pancreatic masses, and therefore the performance of the Franseen and standard needles for evaluating other solid mass lesions could not be evaluated. A second limitation was the small number of patients. Maybe we could have detected a greater diagnostic accuracy in the Franseen needle group with a larger number of patients. Third, we did not compare the performance of the strategies of sampling, i.e., stylet retraction vs suction. This comparison was not among the study aims, and the sample size was not gauged for it. Finally, the pathologist was masked to the type of needle. However, the pathologist evaluated all the processed slides and cell blocks of a specific patient at once. It is possible that the results of the interpretation of the specimen obtained with one needle model influenced the interpretation of the specimen obtained with the other needle.

In conclusion, for the EUS-guided tissue sampling of solid pancreatic lesions, the Franseen needle obtained a greater tissue area compared to the standard needle. The diagnostic sensitivity and negative predictive value of the Franseen needle was greater for the diagnosis of any PM.

We are grateful to Peetermans J and Rousseau M for their insightful comments on the manuscript text and statistics.

| 1. | Vilmann P, Jacobsen GK, Henriksen FW, Hancke S. Endoscopic ultrasonography with guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in pancreatic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:172-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 405] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Irisawa A, Khor CJ, Rerknimitr R. Current status of diagnostic endoscopic ultrasonography in the evaluation of pancreatic mass lesions. Dig Endosc. 2011;23 Suppl 1:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fabbri C, Polifemo AM, Luigiano C, Cennamo V, Baccarini P, Collina G, Fornelli A, Macchia S, Zanini N, Jovine E, Fiscaletti M, Alibrandi A, D'Imperio N. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration with 22- and 25-gauge needles in solid pancreatic masses: a prospective comparative study with randomisation of needle sequence. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:647-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Madhoun MF, Wani SB, Rastogi A, Early D, Gaddam S, Tierney WM, Maple JT. The diagnostic accuracy of 22-gauge and 25-gauge needles in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of solid pancreatic lesions: a meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2013;45:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Iglesias-Garcia J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Abdulkader I, Larino-Noia J, Eugenyeva E, Lozano-Leon A, Forteza-Vila J. Influence of on-site cytopathology evaluation on the diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) of solid pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1705-1710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Puri R, Vilmann P, Săftoiu A, Skov BG, Linnemann D, Hassan H, Garcia ES, Gorunescu F. Randomized controlled trial of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle sampling with or without suction for better cytological diagnosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:499-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wani S, Early D, Kunkel J, Leathersich A, Hovis CE, Hollander TG, Kohlmeier C, Zelenka C, Azar R, Edmundowicz S, Collins B, Liu J, Hall M, Mullady D. Diagnostic yield of malignancy during EUS-guided FNA of solid lesions with and without a stylet: a prospective, single blind, randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:328-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang Y, Chen Q, Wang J, Wu X, Duan Y, Yin P, Guo Q, Hou W, Cheng B. Comparison of modified wet suction technique and dry suction technique in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for solid lesions: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim HJ, Jung YS, Park JH, Park DI, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Choi KY, Ryu S. Endosonographer's macroscopic evaluation of EUS-FNAB specimens after interactive cytopathologic training: a single-center prospective validation cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:4184-4192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maluf-Filho F, Kumar A, Gerhardt R, Kubrusly M, Sakai P, Hondo F, Matuguma SE, Artifon E, Monteiro da Cunha JE, César Machado MC, Ishioka S, Forero E. Kras mutation analysis of fine needle aspirate under EUS guidance facilitates risk stratification of patients with pancreatic mass. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:906-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mohanty SK, Pradhan D, Sharma S, Sharma A, Patnaik N, Feuerman M, Bonasara R, Boyd A, Friedel D, Stavropoulos S, Gupta M. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine-needle aspiration: What variables influence diagnostic yield? Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sadaf S, Loya A, Akhtar N, Yusuf MA. Role of endoscopic ultrasound-guided-fine needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of lymphoma of the pancreas: A clinicopathological study of nine cases. Cytopathology. 2017;28:536-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biopsy using a Franseen needle design: Initial assessment. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:338-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Trevino J, Ramesh J, Varadarajulu S. Randomized trial comparing the 22-gauge aspiration and 22-gauge biopsy needles for EUS-guided sampling of solid pancreatic mass lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bang JY, Hebert-Magee S, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. EUS-guided fine needle biopsy of pancreatic masses can yield true histology. Gut. 2018;67:2081-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Noh DH, Choi K, Gu S, Cho J, Jang KT, Woo YS, Lee KT, Lee JK, Lee KH. Comparison of 22-gauge standard fine needle versus core biopsy needle for endoscopic ultrasound-guided sampling of suspected pancreatic cancer: a randomized crossover trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vanbiervliet G, Napoléon B, Saint Paul MC, Sakarovitch C, Wangermez M, Bichard P, Subtil C, Koch S, Grandval P, Gincul R, Karsenti D, Heyries L, Duchmann JC, Bourgaux JF, Levy M, Calament G, Fumex F, Pujol B, Lefort C, Poincloux L, Pagenault M, Bonin EA, Fabre M, Barthet M. Core needle versus standard needle for endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of solid pancreatic masses: a randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1063-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mavrogenis G, Weynand B, Sibille A, Hassaini H, Deprez P, Gillain C, Warzée P. 25-gauge histology needle versus 22-gauge cytology needle in endoscopic ultrasonography-guided sampling of pancreatic lesions and lymphadenopathy. Endosc Int Open. 2015;3:E63-E68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kovacevic B, Toxværd A, Klausen P, Larsen MH, Grützmeier S, Detlefsen S, Karstensen JG, Brink L, Hassan H, Høgdall E, Vilmann P. Tissue amount and diagnostic yield of a novel franseen EUS-FNB and a standard EUS-FNA needle-A randomized controlled study in solid pancreatic lesions. Endosc Ultrasound. 2023;12:319-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Facciorusso A, Wani S, Triantafyllou K, Tziatzios G, Cannizzaro R, Muscatiello N, Singh S. Comparative accuracy of needle sizes and designs for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;90:893-903.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gkolfakis P, Crinò SF, Tziatzios G, Ramai D, Papaefthymiou A, Papanikolaou IS, Triantafyllou K, Arvanitakis M, Lisotti A, Fusaroli P, Mangiavillano B, Carrara S, Repici A, Hassan C, Facciorusso A. Comparative diagnostic performance of end-cutting fine-needle biopsy needles for EUS tissue sampling of solid pancreatic masses: a network meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1067-1077.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wong T, Pattarapuntakul T, Netinatsunton N, Ovartlarnporn B, Sottisuporn J, Chamroonkul N, Sripongpun P, Jandee S, Kaewdech A, Attasaranya S, Piratvisuth T. Diagnostic performance of endoscopic ultrasound-guided tissue acquisition by EUS-FNA versus EUS-FNB for solid pancreatic mass without ROSE: a retrospective study. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20:215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Asokkumar R, Yung Ka C, Loh T, Kah Ling L, Gek San T, Ying H, Tan D, Khor C, Lim T, Soetikno R. Comparison of tissue and molecular yield between fine-needle biopsy (FNB) and fine-needle aspiration (FNA): a randomized study. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E955-E963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/