Published online Feb 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i2.99906

Revised: January 8, 2025

Accepted: January 17, 2025

Published online: February 16, 2025

Processing time: 194 Days and 15.1 Hours

Stage 1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are best treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for local resection.

To investigate the safety and efficacy of ESD and TEM for local resection of stage 1 rectal NETs.

This retrospective observational analysis included patients with clinical stage 1 rectal NETs (cT1N0M0, less than 20 mm) who underwent ESD or TEM. The ESD and TEM groups were matched to ensure that they had comparable lesion sizes, lesion locations, and pathological grades. We assessed the differences between groups in terms of en bloc resection rate, R0 resection rate, adverse event rate, recurrence rate, and hospital stay and cost.

Totally, 128 Lesions (ESD = 84; TEM = 44) were included, with 58 Lesions within the matched groups (ESD = 29; TEM = 29). Both the ESD and TEM groups had identical en bloc resection (100.0% vs 100.0%, P = 1.000), R0 resection (82.8% vs 96.6%, P = 0.194), adverse event (0.0% vs 6.9%, P = 0.491), and recurrence (0.0% vs 3.4%, P = 1.000) rates. Nevertheless, the median hospital stay [ESD: 5.5 (4.5-6.0) vs TEM: 10.0 (7.0-12.0) days; P < 0.001], and cost [ESD: 11.6 (9.8-12.6) vs TEM: 20.9 (17.0-25.1) kilo-China Yuan, P < 0.001] were remarkably shorter and less for ESD.

Both ESD and TEM were well-tolerated and yielded favorable outcomes for the local removal of clinical stage 1 rectal NETs. ESD exhibits shorter hospital stay and fewer costs than TEM.

Core Tip: Few studies have directly compared the results of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) for rectal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) ≤ 20 mm in size, and there is still no agreement on which treatment is safer and more effective. This research analyzed 128 Lesions who were diagnosed with rectal NETs and treated with ESD or TEM. We found that both ESD and TEM were safe and effective for local resection of stage 1 rectal NETs, with a more reduced hospital stay and lower overall costs, we also discovered that ESD was more cost-effective than TEM.

- Citation: Weng J, Chi J, Lv YH, Chen RB, Xu GL, Xia XF, Bai KH. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for stage 1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(2): 99906

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i2/99906.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i2.99906

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in the rectum are rare but may be cancerous. Along with the rise in screening colonoscopies during the past few decades, the frequency of rectal NETs has increased worldwide[1-3]. Research has shown that the majority of rectal NETs (between 80% and 90%) are initially small (less than 20 mm) during a routine colonoscopy[3,4].

The treatment strategies for rectal NETs vary based on their size. For instance, for rectal NETs under 20 mm in diameter that are confined to the mucosa and submucosa, local excision is currently considered a viable option for patients with low-risk lymph node metastases[5-9]. For local excision of rectal NETs, transanal endoscopic microsurgery (TEM) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) are both suggested approaches to obtain a more histologically complete lesion removal with a reduced incidence of residual tissue[10-12]. The benefit of TEM is that it can achieve full-thickness resection without the risk of incomplete resection or tumor spilling, all while preserving enough rectal walls[13,14]. Unfortunately, TEM is a procedure that requires highly experienced personnel. Similar to the setup needed for laparoscopic surgery, the technique also requires an operating room with specific equipment, such as a rigid video endoscope, platform, and long-armed microsurgical instruments. Furthermore, because general anesthesia is required, the extra strain on patients should be considered. With a high R0 resection rate of nearly 90.0%[12,15], ESD is becoming more popular as a method for treating rectal NETs. While the steep learning curve of the technique is something to consider, tiny rectal lesions like NETs make it reasonably easy to operate.

Few studies have directly compared the results of ESD and TEM for rectal NETs ≤ 20 mm in size[11,16,17], and there is still no agreement on which treatment is safer and more effective. Subsequently, the purpose of this study was to assess the safety and effectiveness of ESD and TEM for stage 1 rectal NETs.

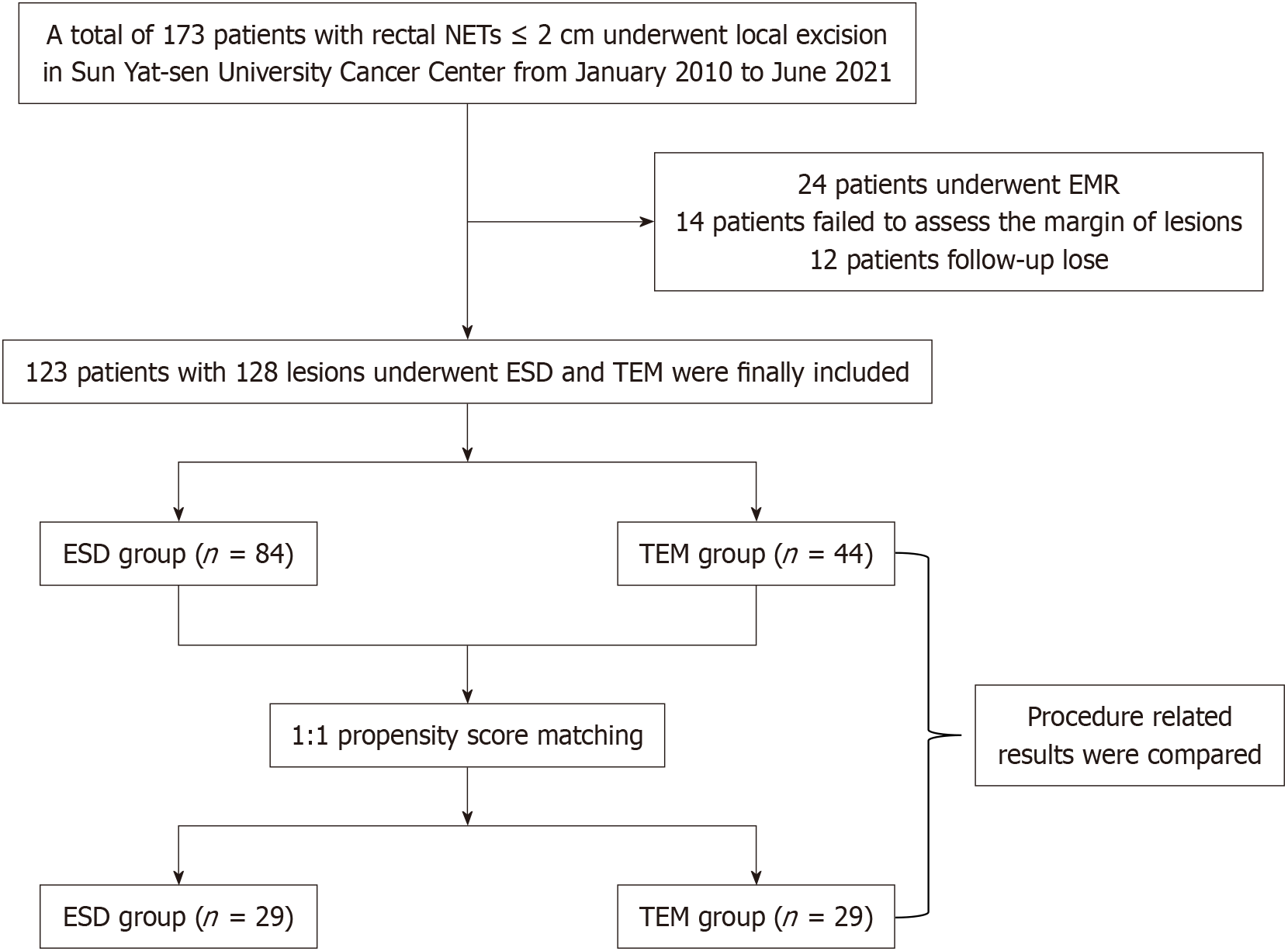

Figure 1 shows the workflow of a retrospective recruitment of 123 patients treated for rectal NETs at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Centre between 2010 and 2021, with 128 lesions analyzed of clinical stage 1 (cT1N0M0)[6]. Before the local resection, all patients underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT), or endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) to determine the depth of invasion and to check for distant metastases or involvement of local lymph nodes. The lesions were endoscopically resected using either TEM or ESD (including hybrid ESD), and then histological analysis was conducted. The inclusion criteria were: (1) The lesion had to be located in the rectum, precisely 15 cm away from the anus; (2) It had to have a long diameter of less than 20 mm; (3) Before the local resection, there was no sign of invasion into the muscularis propria, engagement of local lymph nodes, or distant metastases in the examinations conducted using EUS/MRI/CT; and (4) Immunohistochemical, and Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the resected lesions confirmed the diagnosis of NETs. Patients with NETs in conjunction with other malignant tumor types were not eligible for inclusion in the study, as were individuals whose follow-up time was shorter than six months.

All patients had full disclosure of the benefits and hazards of local resection before the treatment. All participants were already asked to give signed informed consent before the operation. So, when this retrospective study was checked by the ethics committee, another informed consent was exempt. All procedures used in this investigation were in accordance with the principles stated in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and any later ethical standards that were relevant to the study. The study was approved by the Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center's Institutional Review Board's Ethics Committee (SL-B2023-722-01).

For ESD, a single-channel endoscope (Olympus Co. in Tokyo, Japan) was used. At the distal end of the endoscope, a transparent hood was attached. After a detailed assessment of the lesion, the lesion was elevated from the muscle layer by a submucosal injection performed nearby. The sodium hyaluronate solution used in this investigation was diluted 1:4 with a standard saline solution. In addition, a little amount of indigo carmine was added to the mixture. After the injection was given, a stationary, flexible snare knife was used to make an incision in the mucosa around the raised lesion. There was still an open mucosal defect.

The selection between ESD or hybrid ESD was determined by the judgment of the endoscopist. In situations where the lesion's location or the presence of submucosal fibrosis rendered full submucosal dissection difficult, hybrid ESD was used to finish the resection[18,19]. In the hybrid ESD process, snaring is used as the last resection technique after the first ESD execution.

Under general anesthesia, the patient underwent TEM procedures. The patient's position changed based on where the tumor was located. A metal dilator was used to enlarge the anal canal to a diameter of 33 mm before inserting the unopened rectoscope. To make the intrarectal space larger, carbon dioxide was inhaled. With the use of an electrocoagulator, the disc-shaped tumor was removed through the whole thickness, all the way to the mesorectal fat tissue. The specimen that was removed was placed on a plate and positioned such that the edges could be examined pathologically. Using full-thickness interrupted absorbable sutures, the rectal wall defect was corrected.

The tumors that had been removed underwent a histological investigation to evaluate factors such as lymphovascular invasion, invasion depth, and the condition of the specimen's resected margin to determine whether the results were positive or negative. The World Health Organization's guidelines was followed in the evaluation of the mitotic rate and Ki-67 index[6,7].

En bloc resection was first defined as a surgical technique in which a lesion or tumor is removed in one whole piece. Operationally, an R0 resection is a surgical surgery in which microscopic examination reveals a negative lateral and vertical border. The term "curative resection" describes a kind of surgery called "R0 resection," in which the whole tumor is removed surgically without any signs of perineurium or vascular invasion.

An open biopsy forceps was used as a reference while evaluating the lesion's size endoscopically. Perforation and prolonged bleeding were among the adverse events. The manifestation of hematochezia and/or melena after endoscopic resection, which requires a second endoscopy to achieve hemostasis, is known as delayed bleeding. The evaluation of endoscopic and/or radiographic data led to the identification of the perforation.

The medical data was examined retrospectively to assess the clinical outcomes. The first clinical follow-up was one to two weeks after the local resection operation. The purpose of the examination was to find out how often adverse events like delayed bleeding occur. It was recommended that, for the first year after the surgical operation, patients who had curative resection would usually have a colonoscopy examination every six months. An annual colonoscopy check was recommended if there were no signs of recurrence. For patients who had non-R0 resection and rejected further surgical intervention, or for patients who had undergone R0 resection but showed signs of vascular invasion, colonoscopy was recommended at 3-, 6-, and 12-month intervals after the surgery. If there was no local recurrence, a yearly colonoscopy was recommended.

Representing continuous variables was done via means and standard deviations, which were appropriate for normally distributed variables. The use of medians and interquartile ranges was instead employed for continuous data that did not exhibit normal distribution. Percentages were commonly employed to depict categorical variables. Variables were compared via a variety of statistical tests, including t-tests, Kruskal-Wallis tests, χ2 tests, and Fisher's exact tests, as appropriate for the data.

Propensity score matching was used to ensure the ESD and TEM groups had comparable lesion sizes, lesion locations, and pathological grades.

We eliminated the missing data. P < 0.05 was used as the significance threshold for a two-tailed test. We used SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., United States) to do our statistical tests.

Figure 1 shows the research flow chart. A total of 128 lesions involving 123 individuals were examined. A total of 61 lesions had ESD, 23 lesions had hybrid ESD, and 44 lesions had TEM. Table 1 displays a summary of the baseline attributes assessments. The median lesion size was 8.0 (5.5-10.0) mm and 8.0 (5.0-10.0) mm (P = 0.716), the mean ages were 44.7 ± 13.5 years and 45.3 ± 12.2 years (P = 0.491), and the percentage of males was 60.0% and 68.2% (P = 0.221) in the ESD and TEM groups. Moreover, 10.7% of patients in the ESD group and 34.1% of cases in the TEM group were classified as G2 (P < 0.001), based on the classification of mitoses and the Ki-67 proliferation index. Gender, location, invasion depth, vascular invasion, and perineural invasion did not remarkably vary between the two groups.

| Variables | Total (n = 128) | Matched set (n = 58) | ||||

| ESD (n = 84) | TEM (n = 44) | P value | ESD (n = 29) | TEM (n = 29) | P value | |

| Lesion size, mm, median (IQR) | 8.0 (5.5-10.0) | 8.0 (5.0-10.0) | 0.716 | 5.0 (5.0-10.0) | 5.0 (5.0-10.0) | 1.000 |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 44.7 ± 13.5 | 45.3 ± 12.2 | 0.491 | 44.8 ± 14.7 | 41.9 ± 9.9 | 0.293 |

| Follow-up time, month, median (IQR) | 27.0 (15.0-45.0) | 26.5 (16.0-38.0) | 0.934 | 23.0 (12.0-34.0) | 24.0 (16.0-32.0) | 0.828 |

| Male | 45 (60.0) | 30 (68.2) | 0.221 | 15 (51.7) | 21 (72.4) | 0.104 |

| Location | ||||||

| Anus ≤ 5 cm | 32 (38.1) | 23 (52.3) | 0.124 | 13 (44.8) | 14 (48.3) | 0.792 |

| Anus > 5 cm | 52 (61.9) | 21 (47.7) | 16 (55.2) | 15 (51.7) | ||

| Histological grade | ||||||

| G1 | 75 (89.3) | 29 (65.9) | 0.001 | 26 (89.7) | 26 (89.7) | 1.000 |

| G2 | 9 (10.7) | 15 (34.1) | 3 (10.3) | 3 (10.3) | ||

| Invasion depth | ||||||

| Mucosa | 6 (7.1) | 2 (4.5) | 0.714 | 2 (6.9) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 |

| Submucosa | 78 (92.9) | 42 (95.5) | 27 (93.1) | 28 (96.6) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | / |

| Perineural invasion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.344 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | / |

The chosen variables were evenly distributed across the two groups in the matched cohort (ESD, n = 29; TEM, n = 29), as Table 1 demonstrates. In the ESD group, the lesion size was 5.0 (5.0-10.0) mm, whereas in the TEM one, it was 5.0 (5.0-10.0) mm (P = 1.000). Between the two groups, the G2 grade rates were also comparable (10.3% vs 10.3%, P = 1.000).

Results comparing the ESD and TEM groups are shown in Table 2. For both cohorts, the en bloc resection rate yielded a 100.0% success rate. The rate of R0 resection in the ESD was 86.9%, whereas it was 97.7% in the TEM group (P = 0.057). There were no remarkable changes in the rates of procedure-related adverse events (3.6% vs 4.5%, P = 1.000) or recurrence (0.0% vs 2.3%, P = 0.348) between the two groups.

| Variables | Total (n = 128) | Matched set (n = 58) | ||||

| ESD (n = 84) | TEM (n = 44) | P value | ESD (n = 29) | TEM (n = 29) | P value | |

| Hospital day, day, median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) | 9.0 (7.0-12.0) | < 0.001 | 5.5 (4.5-6.0) | 10.0 (7.0-12.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cost, kilo-CNY, median (IQR) | 11.2 (9.6-12.6) | 21.3 (17.4-26.7) | < 0.001 | 11.6 (9.8-12.6) | 20.9 (17.0-25.1) | < 0.001 |

| Anesthesia type | ||||||

| Awake | 48 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 | 17 (58.6) | 0 (0.0) | < 0.001 |

| Venous sedation | 36 (42.9) | 0 (0.0) | 12 (41.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Tracheal intubation | 0 (0.0) | 44 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (100.0) | ||

| Adverse event | 3 (3.6) | 2 (4.5) | 1.000 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (6.9) | 0.491 |

| En bloc resection | 84 (100.0) | 44 (100.0) | / | 29 (100.0) | 29 (100.0) | / |

| R0 resection | 73 (86.9) | 43 (97.7) | 0.057 | 24 (82.8) | 28 (96.6) | 0.194 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0.348 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 |

In the matched cohort, there were comparable rates of en bloc resection (100.0% vs 100.0%), R0 resection (82.8% vs 96.6%, P = 0.194), adverse events (0.0% vs 6.9%, P = 0.491), and recurrence (0.0% vs 3.4%, P = 1.000).

Results of cost-effectiveness were shown in Table 2. While all patients in the TEM group had tracheal intubation anesthesia, all patients in the ESD group underwent the treatment while awake or under intravenous sedation. The mean hospital days were 6.0 (5.0-7.0) and 9.0 (7.0-12.0) days (P < 0.001) in the ESD and TEM groups, respectively. The median cost was 11.2 (9.6-12.6) and 21.3 (17.4-26.7) kilo-China Yuan (CNY) (P < 0.001).

In the matched cohort, the ESD group's mean hospital days [5.5 (4.5-6.0) days vs 10.0 (7.0-12.0) days, P < 0.001] and median cost [11.6 (9.8-12.6) kilo-CNY vs 20.9 (17.0-25.1) kilo-CNY, P < 0.001] were considerably lower than those of the TEM group.

Table 3 displays the findings of outcome analyses depending on lesion size. A total of 84 lesions less than 10 mm and 44 lesions larger than 10-20 mm were included in the study. The median lesion size for lesions less than 10 mm was 6.0 (5.0-8.0) mm in the ESD group and 5.0 (4.5-8.0) mm in the TEM group (P = 0.101). For lesions with a diameter of 10-20 mm, the ESD group and TEM group had median lesion sizes of 10.0 (10.0-12.0) mm and 11.0 (10.0-15.0) mm, respectively (P = 0.277). Regarding en bloc resection rate, R0 resection rate, and complication, ESD showed similar results to TEM in lesions with a diameter of less than 10 mm and lesions with a diameter of 10-20 mm. However, in terms of a shorter hospital stay and lower costs, ESD was more economical than TEM.

| Variables | < 10 mm (n = 84) | 10-20 mm (n = 44) | ||||

| ESD (n = 56) | TEM (n = 28) | P value | ESD (n = 28) | TEM (n = 16) | P value | |

| Lesion size, mm, median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0-8.0) | 5.0 (4.5-8.0) | 0.101 | 10.0 (10.0-12.0) | 11.0 (10.0-15.0) | 0.277 |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 44.8 ± 14.1 | 44.3 ± 11.9 | 0.872 | 44.4 ± 12.4 | 47.1 ± 12.9 | 0.513 |

| Follow-up time, month, median (IQR) | 24.5 (12.5-36.0) | 23.0 (15.0-38.0) | 0.962 | 35.0 (20.0-54.0) | 30.0 (22.5-48.0) | 0.798 |

| Hospital day, day, median (IQR) | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) | 9.0 (7.0-11.5) | < 0.001 | 6.0 (5.0-7.0) | 9.0 (7.0-13.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cost, kilo-CNY, median (IQR) | 10.8 (9.5-12.2) | 22.4 (18.3-26.7) | < 0.001 | 11.5 (10.2-12.6) | 20.0 (16.9-24.8) | < 0.001 |

| Adverse event | 1 (1.8) | 1 (3.6) | 1.000 | 2 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) | 1.000 |

| En bloc resection | 56 (100.0) | 28 (100.0) | / | 23 (100.0) | 16 (100.0) | / |

| R0 resection | 50 (89.3) | 27 (96.4) | 0.416 | 23 (82.1) | 16 (100.0) | 0.141 |

| Recurrence | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | / | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) | 0.364 |

Table 4 displayed the characteristics of 12 lesions that did not have a R0 resection. The median lesion size was 8.0 (5.0-10.0) mm, with a mean age of 39.6 ± 9.4 years. One cases were resected by TEM, while 11 Lesions were removed by ESD (P = 0.057). All the 12 lesions were classified as G1. The submucosal layer was penetrated by each of the 12 lesions. No vascular or perineural invasion lesions were discovered. The two groups did not vary significantly in terms of age, gender, location, pathological grade, invasion depth, vascular invasion, or perineural invasion.

| Non-R0 resection, n = 12 | R0 resection, n = 116 | P value | |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 39.6 ± 9.4 | 45.4 ± 13.2 | 0.138 |

| Lesion size, mm, median (IQR) | 8.0 (5.0-10.0) | 8.0 (5.0-10.0) | 0.885 |

| Male | 8 (66.7) | 67 (57.8) | 0.764 |

| Location | |||

| Anus ≤ 5 cm | 5 (41.7) | 50 (43.1) | 0.924 |

| Anus > 5 cm | 7 (58.3) | 66 (56.9) | |

| Resection method | |||

| ESD | 11 (91.7) | 73 (62.9) | 0.057 |

| TEM | 1 (8.3) | 43 (37.1) | |

| Grade | |||

| G1 | 12 (100.0) | 92 (79.3) | 0.121 |

| G2 | 0 (0.0) | 24 (20.7) | |

| Invasion depth | |||

| Mucosal | 0 (0.0) | 8 (6.9) | 1.000 |

| Submucosal | 12 (100.0) | 108 (93.1) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

| Perineural invasion | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.9) | 1.000 |

Our research is the first to prove both ESD and TEM are viable and successful treatment methods with the identical R0 resection rate for the local resection of rectal NETs less than 20 mm, through direct comparison and propensity score matching between these 2 treatments. With a more reduced hospital stay and lower overall costs, we also discovered that ESD was more cost-effective than TEM. Also, compared to TEM, ESD is simpler. Subsequently, for rectal NETs less than 20 mm, we suggest that ESD might be a good alternative. It should be noted that in lesions that were 10-20 mm in size, the median size was 10.0 (10.0-12.0) mm in the ESD group and 11.0 (10.0-15.0) mm in the TEM group (P = 0.277). Hence, the results of our study are more likely favor the safety and efficacy of ESD as a viable treatment option for rectal NETs less than 15 mm.

In the context of rectal NETs less than 20mm, both ESD and TEM have shown promising results with high percentages of complete resection (R0). However, there have not been much data comparing the two approaches. According to Jeon et al[17], in rectal NETs, ESD (82.6% R0 resection rate) was like TEM (100% R0 resection rate), but better than endoscopic mucosal resection (65.5% R0 resection rate). Nevertheless, there were only 14 cases in the TEM group, so it might be possible that the sample size was not large enough to establish a difference. Park et al[11] conducted a retrospective study on 285 cases with rectal NETs less than 20 mm. Out of these patients, 226 had ESD procedures and 59 underwent TEM procedures. Comparing the ESD and TEM groups, they found no statistically significant difference in the R0 resection rate (81.9% vs 91.5%, P = 0.072). However, R0 resection rate was lower in ESD than TEM following propensity score matching (71.2% vs 92.3%, P = 0.005). Of the 114 cases of rectal NETs less than 20 mm that were retrospectively studied by Jin et al[16], 55 were treated with ESD and 59 with TEM. Compared to the TEM group, the ESD one had a reduced R0 resection rate (70.9% vs 91.5%, P = 0.005). Nevertheless, it is important to mention that compared to earlier investigations, the R0 resection rate for ESD in these two studies, was much lower, at only about 70.0%.

Consistent with previous studies[20-22], our analysis found a R0 resection rate of 86.9% in the ESD group. A meta-analysis of 14 articles covering 823 cases of rectal NETs removed endoscopically was carried out by Pan et al[23]. Their findings showed that 90.2% of cases resulted in R0 resections. In the case of ESD, the R0 resection rate was at 84.1%. In their meta-analysis, Yong et al[12] pooled data from 22 studies reporting 1360 instances of rectal NETs. The results showed that out of 655 ESD patients, 92.0% had R0 resections. Consistent with our findings, Li et al[15] concluded that 88.7% of rectal NETs could be completely removed via endoscopy out of 101 cases.

It is important to carefully evaluate the strengths and limitations of the current study. This study might be interesting because it compared the effectiveness and safety of ESD with TEM in treating stage 1 rectal NETs in individuals who were clinically matched. However, this study had limitations, such as a small sample size and the fact that most of the cases examined had a diameter smaller than 10 mm. Only a small percentage of cases had rectal NETs of 10 to 20 mm. Therefore, large-scale trials might be needed for further validation of the current findings. Secondly, while comparing the results of ESD with TEM, it is vital to consider that the current study is retrospective and single center, and the choice for ESD or TEM was not standardized and was made by the appointed endoscopist, which might introduce selection bias. In patients with comorbidities that make general anesthesia a high risk, or patients who would have chosen less invasive procedures without anesthesia, ESD may have been preferred. In addition, the physician’s opinion could have had a significant role in deciding which operation to do, depending on the size of the tumor. For individuals with rectal NETs larger than 10 mm, the surgeon may have opted for TEM. To reduce the impact of selection bias, we balanced the groups based on their clinical features using the propensity score matching approach. However, there are still other confounding variables in this study. Finally, the length of time that some patients were followed up with was short. A fourth consideration that may have an impact on R0 resection of ESD is the lack of knowledge on the kinds of snare knives used.

Both ESD and TEM are safe and effective procedures for local resection of stage 1 rectal NETs. ESD may be a suitable alternative to TEM for obtaining complete removal (R0 resection) of rectal NETs that are less than 20 mm. In addition, ESD exhibits shorter hospital stay and fewer costs than TEM. Extensive, prospective, randomized trials are required to verify these suggestions.

| 1. | Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Powers BD, Davey A, Willis AI. Examining rectal carcinoids in the era of screening colonoscopy: a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:952-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Jung YS, Yun KE, Chang Y, Ryu S, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, Park DI. Risk factors associated with rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a cross-sectional study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1406-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Weinstock B, Ward SC, Harpaz N, Warner RR, Itzkowitz S, Kim MK. Clinical and prognostic features of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology. 2013;98:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McDermott FD, Heeney A, Courtney D, Mohan H, Winter D. Rectal carcinoids: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2020-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rinke A, Ambrosini V, Dromain C, Garcia-Carbonero R, Haji A, Koumarianou A, van Dijkum EN, O'Toole D, Rindi G, Scoazec JY, Ramage J. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for colorectal neuroendocrine tumours. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35:e13309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Shah MH, Goldner WS, Benson AB, Bergsland E, Blaszkowsky LS, Brock P, Chan J, Das S, Dickson PV, Fanta P, Giordano T, Halfdanarson TR, Halperin D, He J, Heaney A, Heslin MJ, Kandeel F, Kardan A, Khan SA, Kuvshinoff BW, Lieu C, Miller K, Pillarisetty VG, Reidy D, Salgado SA, Shaheen S, Soares HP, Soulen MC, Strosberg JR, Sussman CR, Trikalinos NA, Uboha NA, Vijayvergia N, Wong T, Lynn B, Hochstetler C. Neuroendocrine and Adrenal Tumors, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:839-868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ramage JK, De Herder WW, Delle Fave G, Ferolla P, Ferone D, Ito T, Ruszniewski P, Sundin A, Weber W, Zheng-Pei Z, Taal B, Pascher A; Vienna Consensus Conference participants. ENETS Consensus Guidelines Update for Colorectal Neuroendocrine Neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103:139-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zheng Y, Guo K, Zeng R, Chen Z, Liu W, Zhang X, Liang W, Liu J, Chen H, Sha W. Prognosis of rectal neuroendocrine tumors after endoscopic resection: a single-center retrospective study. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2021;12:2763-2774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chen X, Li B, Wang S, Yang B, Zhu L, Ma S, Wu J, He Q, Zhao J, Zheng Z, Li S, Wang T, Liang L. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors: a 10-year data analysis of Northern China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:384-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang FG, Jiang Y, Liu C, Qi H. Comparison between Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection and Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery in Early Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumor Patients: A Meta-Analysis. J Invest Surg. 2023;36:2278191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Park SS, Kim BC, Lee DE, Han KS, Kim B, Hong CW, Sohn DK. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery for T1 rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a propensity score-matched study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94:408-415.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yong JN, Lim XC, Nistala KRY, Lim LKE, Lim GEH, Quek J, Tham HY, Wong NW, Tan KK, Chong CS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal carcinoid tumor. A meta-analysis and meta-regression with single-arm analysis. J Dig Dis. 2021;22:562-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lie JJ, Yoon HM, Karimuddin AA, Raval MJ, Phang PT, Ghuman A, Lee LH, Stuart H, Brown CJ. Management of rectal neuroendocrine tumours by transanal endoscopic microsurgery. Colorectal Dis. 2023;25:1026-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brand M, Reimer S, Reibetanz J, Flemming S, Kornmann M, Meining A. Endoscopic full thickness resection vs. transanal endoscopic microsurgery for local treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors - a retrospective analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36:971-976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li D, Xie J, Hong D, Liu G, Wang R, Jiang C, Ye Z, Xu B, Wang W. Efficacy and safety of ligation-assisted endoscopic submucosal resection combined with endoscopic ultrasonography for treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2022;1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jin R, Bai X, Xu T, Wu X, Wang Q, Li J. Comparison of the efficacy of endoscopic submucosal dissection and transanal endoscopic microsurgery in the treatment of rectal neuroendocrine tumors ≤ 2 cm. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1028275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jeon JH, Cheung DY, Lee SJ, Kim HJ, Kim HK, Cho HJ, Lee IK, Kim JI, Park SH, Kim JK. Endoscopic resection yields reliable outcomes for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:556-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Esaki M, Ihara E, Sumida Y, Fujii H, Takahashi S, Haraguchi K, Iwasa T, Somada S, Minoda Y, Ogino H, Tagawa K, Ogawa Y. Hybrid and Conventional Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Neoplasms: A Multi-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:1810-1818.e8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McCarty TR, Bazarbashi AN, Thompson CC, Aihara H. Hybrid endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) compared with conventional ESD for colorectal lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2021;53:1048-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim J, Kim JH, Lee JY, Chun J, Im JP, Kim JS. Clinical outcomes of endoscopic mucosal resection for rectal neuroendocrine tumor. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li Y, Pan F, Sun G, Wang ZK, Meng K, Peng LH, Lu ZS, Dou Y, Yan B, Liu QS. Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes of 54 Cases of Rectal Neuroendocrine Tumors with Incomplete Resection: A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2021;17:1153-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cha JH, Jung DH, Kim JH, Youn YH, Park H, Park JJ, Um YJ, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH, Lee HJ. Long-term outcomes according to additional treatments after endoscopic resection for rectal small neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pan J, Zhang X, Shi Y, Pei Q. Endoscopic mucosal resection with suction vs. endoscopic submucosal dissection for small rectal neuroendocrine tumors: a meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1139-1145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/