Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.111614

Revised: July 30, 2025

Accepted: November 13, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 164 Days and 16 Hours

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage using lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) has emerged as the first-line approach for managing walled-off necrosis (WON). However, certain patients require escalation to direct endoscopic necro

To determine the predictors of direct endoscopic necrosectomy following LAMS placement in patients with WON and to assess the clinical outcomes and safety.

A retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from patients with acute pancreatitis who were admitted to the Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Post

A total of 104 patients with symptomatic pancreatic WON who underwent LAMS placement were included in this study. Of these, 36 required endoscopic necro

Early identification of these predictive variables can guide treatment planning for WON and facilitate early necrosectomy, thereby improving the clinical outcomes.

Core Tip: Walled-off necrosis (WON) is a well-known complication of acute pancreatitis. Although many patients respond to endoscopic drainage alone, some require direct endoscopic necrosectomy for optimal outcomes. This retrospective study identified the clinical, biochemical, and radiological predictors of necrosectomy in patients undergoing placement of lumen-apposing metal stents. Of the examined factors, fever, anemia, hypoalbuminemia, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, pancreatic necrosis > 30%, WON size, and WON location were predictors of necrosectomy. Early identification of these predictors can guide clinicians in planning timely interventions, thereby improving outcomes and reducing morbidity associated with delayed or unnecessary necrosectomy.

- Citation: Lone SA, Sonika U, Reddy RT, Vaithiyam V, Aneesh PS, Palli SH, Dalal A, Kumar A, Srivastava S, Sachdeva S. Predictive factors and outcomes of endoscopic necrosectomy in patients with acute pancreatitis and walled-off necrosis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(12): 111614

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i12/111614.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i12.111614

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is one of the most common gastrointestinal causes of hospitalization worldwide[1]. While most patients (80%) experience a mild and self-limiting course, 10%-20% of patients with AP develop severe disease characterized by necrosis of the pancreatic parenchyma or extrapancreatic adipose tissue[2]. These patients exhibit a complex, prolonged clinical course with organ failure and local and systemic complications, leading to high morbidity and associated mortality of up to 20%-30%[3].

Pancreatic and peripancreatic collections are well-recognized complications of AP. According to the revised Atlanta classification, these collections are classified into peripancreatic fluid collections, acute necrotizing collections, pseudocysts, and walled-off necrosis (WON), depending on the amount of debris and the time elapsed since the onset of pancreatitis[4]. WON is characterized by a mature encapsulated collection of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrotic tissue that occurs 4 weeks after disease onset. Approximately 50% of patients with WON are asymptomatic and may experience spontaneous resolution within 6 months of onset[5]. WON drainage is indicated in patients with superadded infections, persistent abdominal pain, anorexia, weight loss, gastrointestinal obstruction, or biliary obstruction[6].

In recent years, there has been a paradigm shift in the management of WON from surgical drainage to noninvasive percutaneous or endoscopic routes. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage has been simplified by the deve

Approximately 60%-80% of patients with WON undergoing endoscopic treatment respond well to transmural drainage alone[6]. Nonetheless, a subset of patients may require additional direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN) because of persistent symptoms, infection, or inadequate drainage[10,11]. Identifying the predictors of necrosectomy remains challenging in clinical practice. Several imaging and clinical parameters have been assessed as potential predictors of necrosectomy. Factors such as the extent of necrosis (> 30%-50%), paracolic extension, non-homogeneous or loculated collections, and signs of infection have been implicated[10,12-14]. Furthermore, the timing of DEN - whether performed immediately at the time of stent placement or delayed - has emerged as a variable that may potentially affect the out

This single-center retrospective observational study was conducted at the Department of Department of Gastroenterology, Govind Ballabh Pant Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, New Delhi, between January 2020 and October 2023. All adult patients (≥ 18 years of age) diagnosed with WON based on the revised Atlanta classification and who underwent EUS-guided drainage with LAMS placement were included[4,7]. EUS-guided cystogastrostomy or cystoduodenostomy was performed in patients with symptomatic WON, including those with infection, anorexia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal or biliary tract obstruction. Patients with asymptomatic WON, pancreatic pseudocysts, prior surgical or percutaneous catheter drainage, or incomplete clinical or imaging follow-up were excluded from the study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, No. F.1/IEC/MAMC/85/04/2021/No. 470.

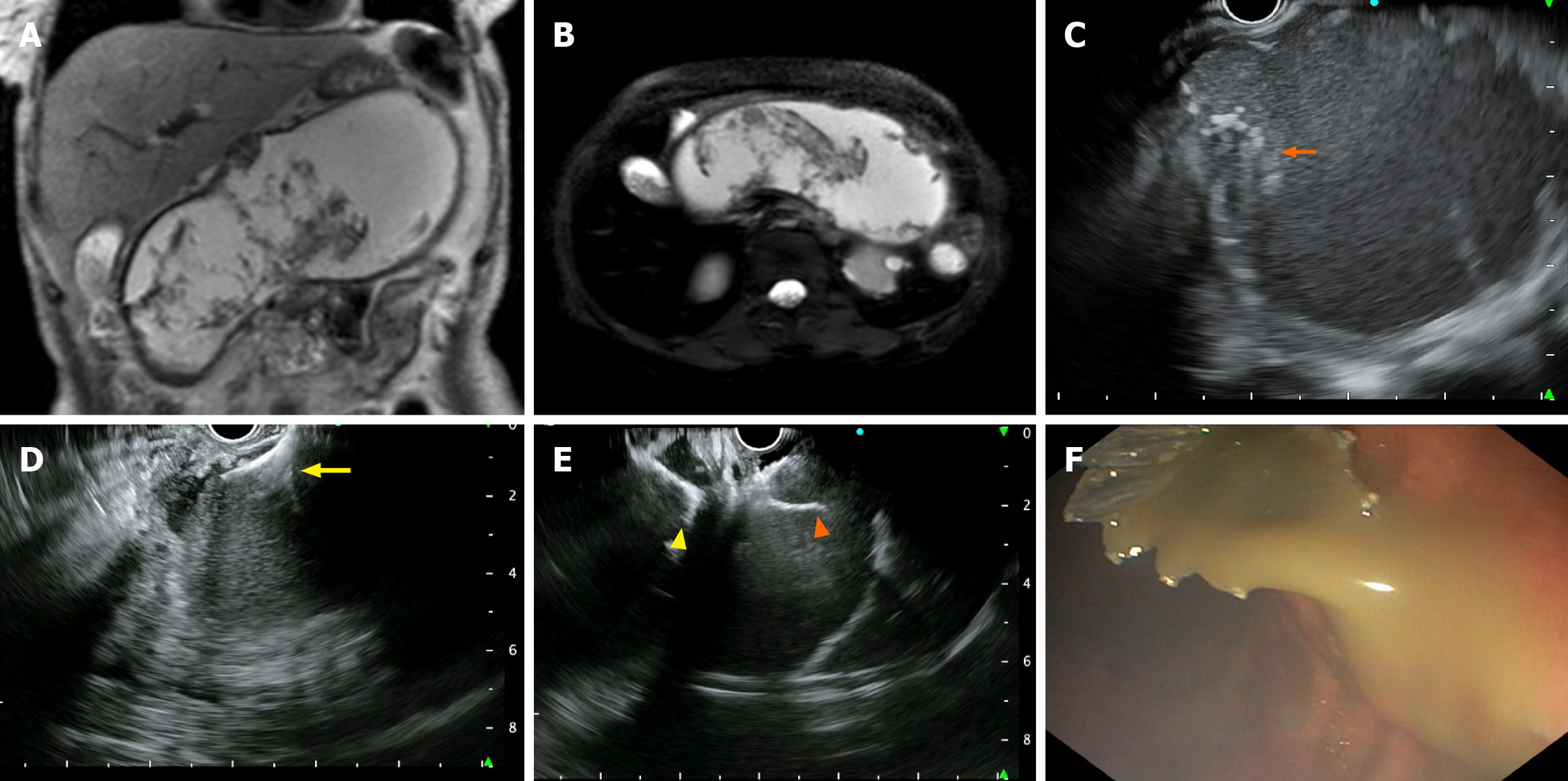

EUS-guided cystogastrostomy: An experienced therapeutic endoscopist performed all procedures using a linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) under intravenous anesthesia. The collection was identified, and a cautery-enhanced bi-flange stent (EASE®, Scientific Healthcare, Faridabad, India) with a diameter of 16 mm and a length of 3 cm was deployed using the transgastric or transduodenal approach (Figure 1). Patients were monitored for symptom resolution and underwent repeat imaging (computed tomography or ultrasound) if symptoms persisted or at 4 weeks before stent removal. Antibiotics were administered either empirically or based on the results of microbial culture.

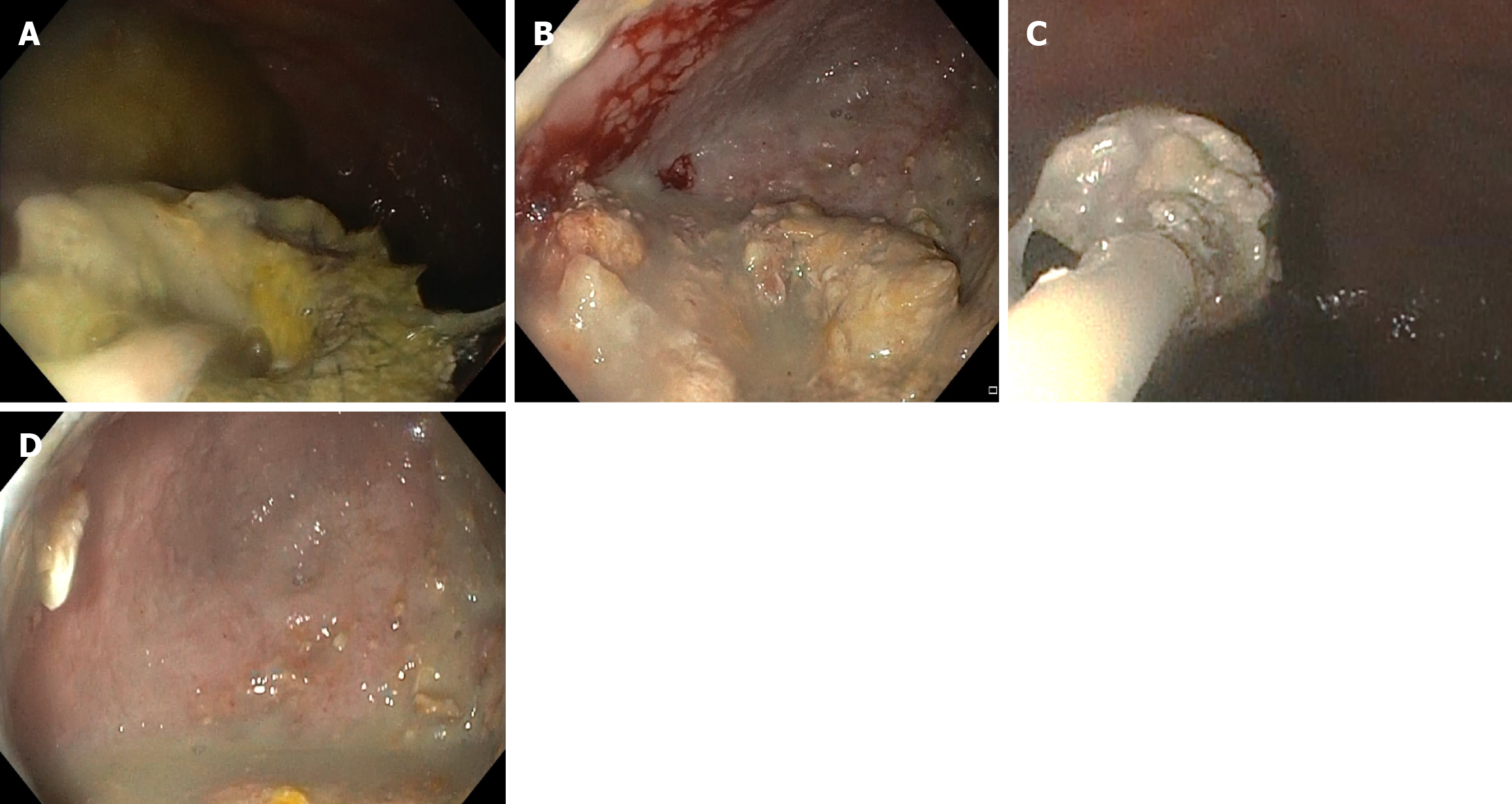

DEN: DEN was performed only for those who required it based on their clinical condition, such as persistent sepsis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), or incomplete resolution of WON. A forward-viewing endoscope (GF-UCT180; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was introduced into the cyst cavity through the indwelling LAMS, and the position of the metallic stent was identified. Any obstruction in the stent was cleared, and the cyst cavity was assessed for the presence of pus, debris, and the cyst wall. Snares, forceps, or baskets were used for debridement, and betadine irrigation was performed at the end of the procedure (Figure 2). The procedure was repeated only if necessary, based on the persistence of symptoms.

If imaging confirmed the resolution of WON, LAMS was removed 4 weeks after insertion[16]. If patients had persistent symptoms and incomplete WON resolution, the stents were removed, and 10 Fr × 7 cm double-pigtail plastic stents were placed[17].

Primary objective: To identify the clinical and radiological predictors of the need for endoscopic necrosectomy after LAMS placement.

Secondary objectives: To assess technical success, clinical success, and adverse events. To evaluate recurrence, reintervention, and mortality rates over 6 months.

Technical success: Accurate deployment of LAMS into the WON cavity under EUS guidance[18].

Clinical success: Resolution of symptoms, with ≥ 50% reduction in WON size on imaging within 4 weeks[19].

Necrosectomy: Endoscopic removal of necrotic debris through the LAMS tract.

Clinical failure: Reintervention need, recurrence, or death within 6 months of drainage.

Adverse events: Any complications following the procedure, such as infection, bleeding, pseudoaneurysm, stent mig

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). All patient data were anonymized prior to analysis. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median with interquartile range and were compared using the independent samples t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact test.

Variables identified in the univariate analysis were subjected to receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to determine their predictive accuracy of the need for necrosectomy. Variables with P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors of necrosectomy. The predicted probabilities from the final multivariate model were subsequently used to generate an ROC curve and calculate the area under the curve (AUC), assessing the model’s discriminatory performance. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

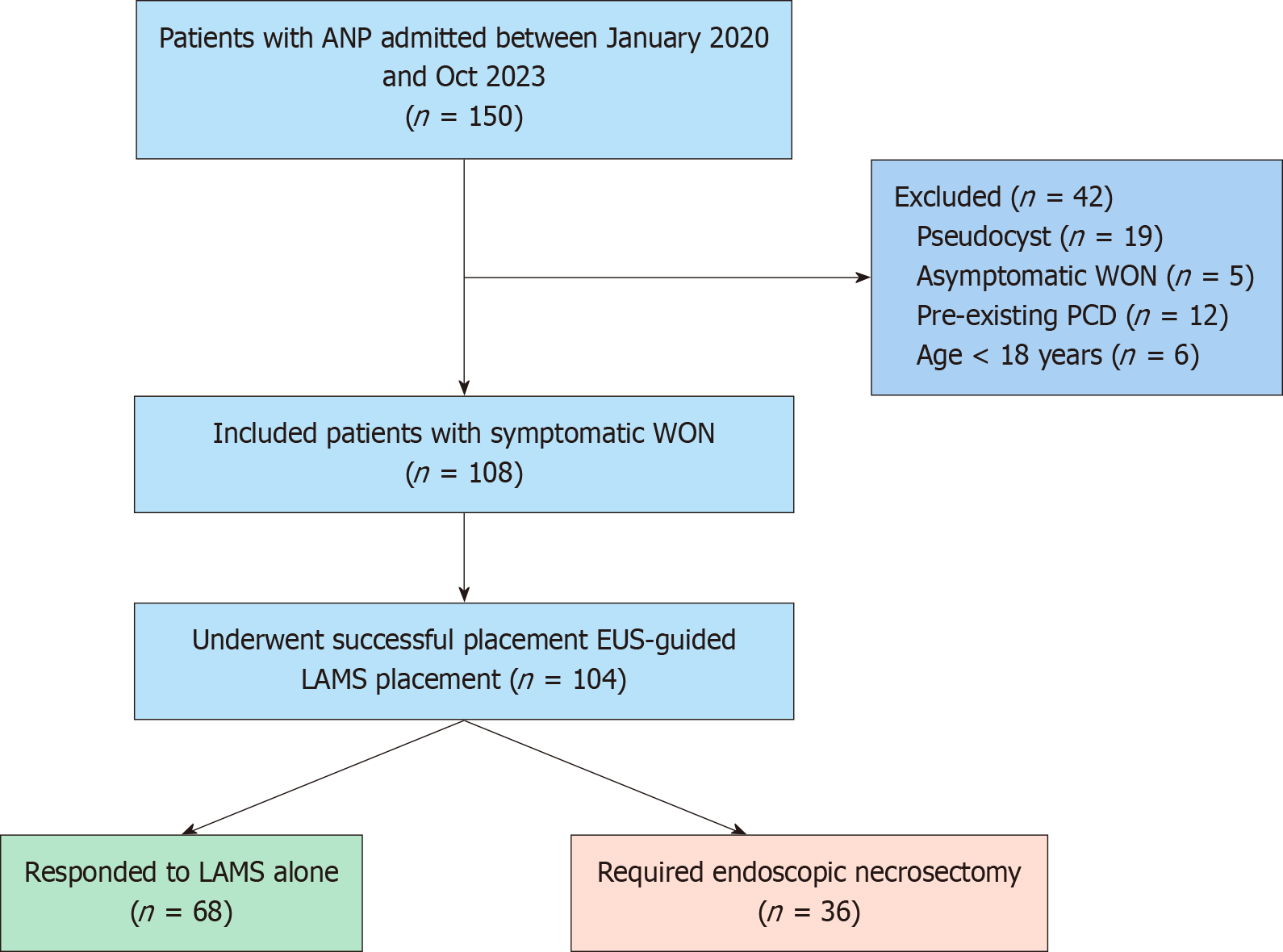

During the study period, 108 patients with symptomatic WON underwent EUS-guided LAMS placement. EUS-guided LAMS were successfully placed in 104 patients with WON. In two patients, the cyst cavity could not be punctured, and in two others, the LAMS was misdeployed inside the collection (technical success: 96.2%). Of the 104 patients, 36 (34.6%) required subsequent endoscopic necrosectomy, and the remaining 68 (65.4%) were managed successfully with LAMS alone (Figure 3). The two groups were comparable in terms of age and sex. The mean age of the study group was 34.93 ± 11.81 years. The most common etiology of AP in both groups was biliary (41 patients, 39.4%), followed by alcohol (38 patients, 36.5%). Furthermore, the most common indication for LAMS insertion in both groups was abdominal pain; however, fever as an indication was more prevalent in the necrosectomy group [odds ratio (OR) = 4.47, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.85-10.79, P = 0.001]. Systemic complications, such as acute kidney injury, acute lung injury, and intensive care unit admission, were comparable between the groups; nonetheless, SIRS was more frequent in the necrosectomy group than in the LAMS-alone group (OR = 5.85, 95%CI: 2.03-16.83, P = 0.001) (Table 1). Furthermore, anemia (OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.04-1.34, P = 0.001) and hypoalbuminemia (OR = 0.330, 95%CI: 0.163-0.667, P = 0.001) were predictors of necrosectomy in the univariate analysis.

| Variable | Total (n = 104) | Necrosectomy group (n = 36) | Non-necrosectomy group (n = 68) | P value |

| Demographic parameters | ||||

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 34.93 ± 11.81 | 38.08 ± 10.82 | 33.26 ± 12.03 | 0.047 |

| Gender | 0.258 | |||

| Male | 79 | 25 | 54 | |

| Female | 25 | 11 | 14 | |

| Smoking | 20 (19.2) | 7 (19.4) | 13 (19.1) | 0.968 |

| Alcohol | 37 (35.5) | 12 (33.3) | 25 (36.7) | 0.728 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| HTN | 3 (2.8) | 1 (2.7) | 2 (2.9) | 0.717 |

| Diabetes mellites | 6 (5.7) | 3 (8.3) | 3 (4.4) | 1.000 |

| Etiology | ||||

| Alcohol | 38 (36.5) | 12 (33.3) | 26 (38.2) | 0.788 |

| Biliary | 41 (39.4) | 16 (44.4) | 25 (36.7) | 0.564 |

| Traumatic | 1 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0.453 |

| Idiopathic | 24 (23.0) | 8 (22.2) | 16 (23.5) | 0.788 |

| SIRS | 66 (63.4) | 31 (86.1) | 35 (51.5) | 0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 7 (6.7) | 4 (11.1) | 3 (4.4) | 0.195 |

| Acute lung injury | 10 (9.6) | 5 (13.8) | 5 (7.3) | 0.280 |

| ICU admission | 32 (30.7) | 15 (41.6) | 17 (25) | 0.080 |

| Indication of metallic stent insertion | ||||

| Pain | 98 (94.2) | 34 (94.4) | 64 (94.1) | 0.946 |

| Fever | 51 (49.0) | 26 (72.2) | 25 (36.7) | 0.001 |

| Jaundice | 8 (7.6) | 4 (11.1) | 4 (5.8) | 0.341 |

| Vomiting | 10 (9.6) | 2 (5.5) | 8 (11.7) | 0.307 |

| Lump | 5 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 5 (7.3) | 0.095 |

| Time from AP to LAMS (days) | 49.04 ± 24.22 | 44.64 ± 23.89 | 51.38 ± 24.25 | 0.178 |

| Hematological and Biochemical parameters, mean ± SD | ||||

| Haemoglobin (gm/dL) | 10.1 ± 1.86 | 9.23 ± 1.66 | 10.55 ± 1.81 | 0.001 |

| Total leucocyte count/mm³ | 14341 ± 8054 | 17372 ± 7742 | 12908 ± 7805 | 0.006 |

| Platelets (lac/mm3) | 3.24 ± 1.37 | 3.30 ± 1.38 | 3.2074 ± 1.38 | 0.742 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 26.4 ± 22.5 | 30.58 ± 32.72 | 24.19 ± 14.52 | 0.171 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.635 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.86 ± 1.027 | 1.03 ± 0.751 | 1.51 ± 0.631 | 0.186 |

| AST (IU/L) | 33.08 ± 23.8 | 39.17 ± 35.1 | 29.8 ± 14.06 | 0.580 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 24.5 ± 23.32 | 26.8 ± 31 | 23.3 ± 18 | 0.466 |

| ALP (IU/L) | 151.4 ± 94.8 | 186.5 ± 122 | 133 ± 70 | 0.006 |

| Total protein (gm/dL) | 6.72 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 1.0 | 0.572 |

| Albumin (gm/dL) | 3.2 ± 0.68 | 2.9 ± 0.58 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 0.001 |

| Computed tomography imaging characteristics | ||||

| Size of WON long axis | 12.17 ± 3.76 | 13.48 ± 3.819 | 11.38 ± 3.37 | 0.005 |

| WON location | ||||

| Head | 53 (50.9) | 23 (63.8) | 20 (29.4) | 0.001 |

| Body | 99 (95.1) | 35 (97.2) | 64 (94.1) | 0.481 |

| Tail | 76 (73.0) | 30 (83.3) | 46 (67.6) | 0.086 |

| Entire | 26 (25) | 17 (47.2) | 9 (13.2) | 0.001 |

| Amount of necrosis, mean ± SD | 53.98 ± 22.11 | 71.25 ± 12.5 | 48.09 ± 21.09 | 0.001 |

| < 30% | 21 (20.1) | 1 (2.7) | 20 (29.4) | 0.001 |

| > 30% | 83 (79.8) | 35 (97.2) | 48 (70.5) | |

| CTSI, mean ± SD | 8.02 ± 1.35 | 8.56 ± 1.229 | 7.74 ± 1.334 | 0.003 |

| Extension of WON | 77 (74.0) | 24 (66.6) | 53 (77.9) | 0.284 |

| Pelvic | 2 (1.9) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (1.4) | 1.000 |

| Paracolic | 25 (24.0) | 11 (30.5) | 14 (20.5) | 0.675 |

| Additional drainage | ||||

| PCD | 13 (12.5) | 6 (16.6) | 7 (10.2) | 0.350 |

| DPT1 | 15 (14.4) | 10 (27.7) | 5 (7.3) | 0.005 |

| ENCD through LAMS | 6 (5.7) | 6 (16.6) | 0 (0) | 0.001 |

| Outcome parameters | ||||

| Clinical outcome: Success | 85 (81.7) | 25 (69.4) | 60 (88.2) | 0.022 |

| Hospital stay duration | 16.87 ± 9.64 | 21.56 ± 11.34 | 12.68 ± 7.95 | 0.001 |

| LAMS duration | 28.00 ± 10.22 | 31.21 ± 10.42 | 26.58 ± 9.80 | 0.033 |

| WON recurrence in 6 months | 13 (12.5) | 8 (25) | 5 (7.3) | 0.032 |

| Adverse events | ||||

| Bleeding | 6 (5.7) | 2 (5.5) | 4 (5.8) | 0.356 |

| Stent migration | 11 (10.5) | 7 (19.4) | 4 (5.8) | 0.136 |

| Colonic fistula | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0.561 |

| 6-month mortality | 4 (3.8) | 2 (5.5) | 2 (2.9) | 0.239 |

There was no difference between the two groups in terms of the timing of LAMS insertion relative to the onset of AP. Imaging features, such as the amount of necrosis (OR = 1.082, 95%CI: 1.045-1.120, P = 0.001), pancreatic necrosis > 30% (OR = 14.6, 95%CI: 1.87-113.86, P = 0.001), number of WON (OR = 1.2, 95%CI: 0.504-2.857, P = 0.009), WON located in the pancreatic head (OR = 5.865, 95%CI: 2.248-15.307, P = 0.001), and WON replacing the whole pancreas (OR = 4.246, 95%CI: 1.80-10.0, P = 0.001), computed tomography severity index (CTSI) score > 6 (OR = 1.629, 95%CI: 1.165-2.274, P = 0.03), and WON size in the long axis (OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.04-1.34, P = 0.009) were associated with the need for necrosectomy compared with LAMS alone (Table 1). The extension of the WON to the paracolic gutter or pelvic extension and per

In the multivariate analysis, the amount of necrosis was the only independent predictor of necrosectomy [OR = 1.085, 95%CI: 1.026-1.148), P < 0.004]. The presence of fever and SIRS increased the risk of necrosectomy by > 1.5 times; however, these factors did not reach statistical significance (Table 2). In our study, the timing of DEN was not sta

| Variable | OR | 95%CI lower | 95%CI upper | P value |

| CTSI score | 0.729 | 0.416 | 1.281 | 0.272 |

| Amount of necrosis | 1.085 | 1.026 | 1.148 | 0.004 |

| < 30% or > 30% of necrosis | 0.381 | 0.013 | 10.781 | 0.571 |

| WON location - head | 1.294 | 0.234 | 7.158 | 0.768 |

| WON location - entire | 1.125 | 0.168 | 7.512 | 0.903 |

| Size of WON | 1.095 | 0.897 | 1.337 | 0.371 |

| SIRS | 1.584 | 0.304 | 8.24 | 0.585 |

| Hemoglobin | 0.815 | 0.567 | 1.171 | 0.269 |

| TLC | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.914 |

| Albumin | 0.438 | 0.142 | 1.348 | 0.15 |

| Fever | 1.937 | 0.526 | 7.127 | 0.32 |

| Outcome parameter | First DEN ≤ 7 days (n = 21) | First DEN > 7 days (n = 15) | P value |

| Mean number of DEN sessions | 1.67 ± 0.98 | 1.33 ± 0.49 | 0.244 |

| Clinical success | 16 (76.1) | 12 (80) | 0.806 |

| Hospital stay duration (days), mean ± SD | 22.5 ± 12.7 | 20.3 ± 9.3 | 0.288 |

| WON recurrence within 6 months | 4 (19) | 4 (26.7) | 1.000 |

| 6-month mortality | 1 (4.8) | 1 (6.7) | 1.000 |

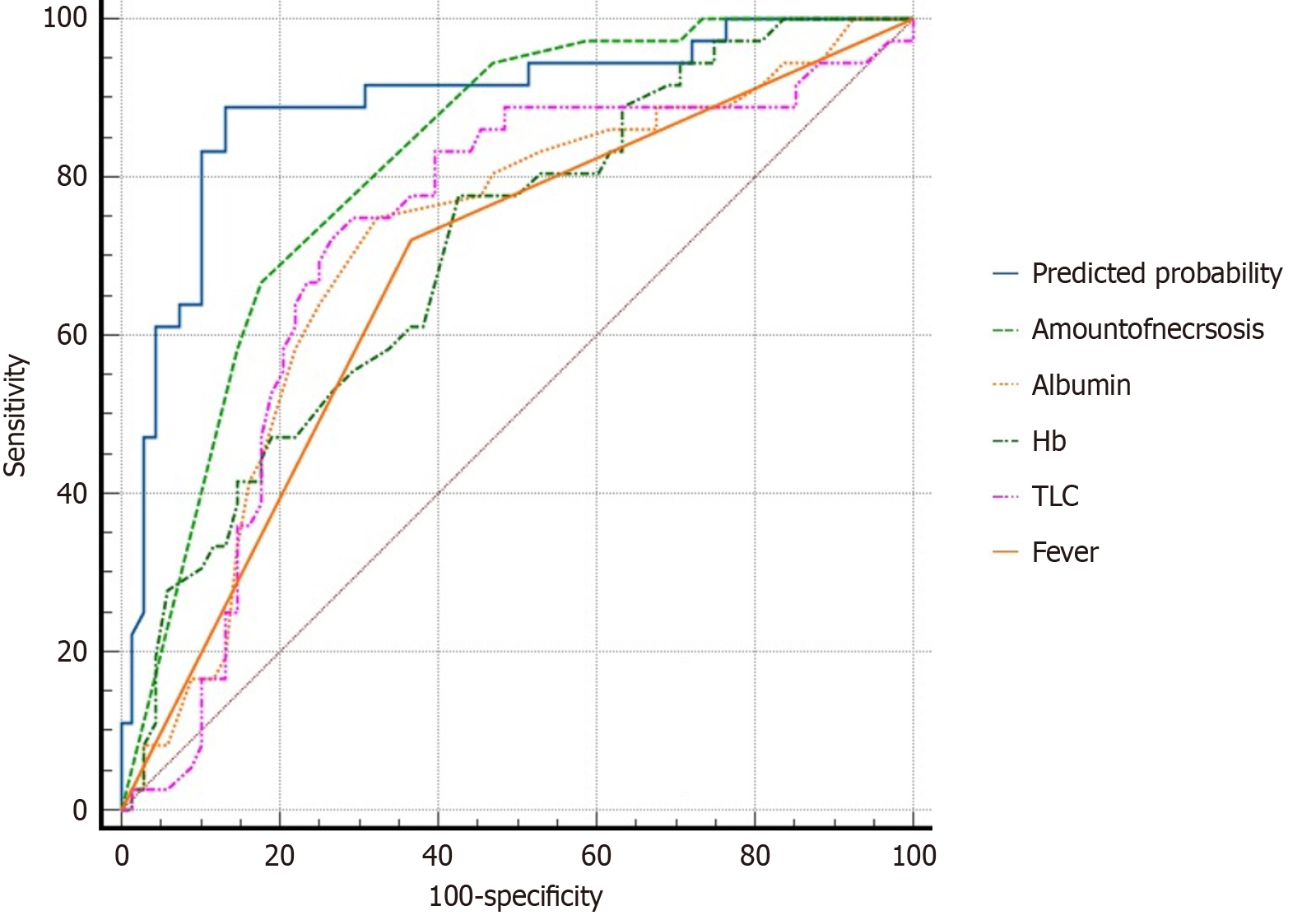

ROC curve analysis was performed to assess the predictive value of the variables identified using univariate analysis for DEN requirement after LAMS placement. Of these variables, the amount of necrosis exhibited excellent predictive accuracy, with an AUC of 0.819. Hypoalbuminemia (AUC = 0.712), anemia (AUC = 0.706), total leukocyte count (AUC = 0.718), and fever (AUC = 0.677) demonstrated good discrimination ability. Factors such as the size of the WON on the long axis (AUC = 0.681), SIRS (AUC = 0.673), and WON involving the entire pancreas (AUC = 0.670) showed fair predictive value. Conversely, necrosis > 30% (AUC = 0.633) and the CTSI score (AUC = 0.659) displayed poor discriminatory ability. The location of WON in the pancreatic head (AUC = 0.500) had no predictive significance. ROC analysis of a multivariate logistic regression model incorporating all variables identified in the univariate analysis showed good discriminatory ability in predicting the need for necrosectomy, with an AUC of 0.892 (95%CI: 0.821-0.962), which was superior to that of the individual parameters (Figure 4).

The overall clinical success rate was 81.7%. Patients requiring necrosectomy exhibited a slightly lower clinical success rate (69.4%) than those treated with LAMS alone (88.2%), and this difference was statistically significant (P = 0.022). Moreover, the mean hospital and LAMS durations were longer in the DEN group than in the LAMS group (Table 1). WON recurrence within 6 months was significantly higher in the necrosectomy group than in the non-necrosectomy group (25% vs 7.3%, P = 0.0032). Procedure-related complications included bleeding, pseudoaneurysm formation, and stent migration. The most common postprocedural complication in the study group was stent migration, followed by bleeding, which was comparable between the two groups. The incidence of pseudoaneurysms was similar between the two groups. At 6 months, four patients died, with two in each group. In the necrosectomy group, one patient developed persistent sepsis and multiorgan failure, and the other died owing to pseudoaneurysm-related hemorrhage. In the LAMS-only group, both patients died from the worsening of sepsis.

In this single-center retrospective analysis of patients who underwent EUS-guided drainage for WON using LAMS, 36 (34.6%) patients required subsequent necrosectomy. The findings indicated that the amount of pancreatic necrosis independently increased the need for necrosectomy by 8.5% (OR = 1.085, 95%CI: 1.026-1.148, P < 0.004). Clinical factors, such as the presence of fever and SIRS, increased the risk of necrosectomy by 4.47 times (OR = 4.47, 95%CI: 1.85-10.79) and 5.85 times (OR = 5.85, 95%CI: 2.03-16.83, P = 0.001), respectively, in univariate analysis. Laboratory parameters, including anemia (AUC = 0.706), leukocytosis (AUC = 0.718), and hypoalbuminemia (AUC = 0.712), had good predictive value for the need for necrosectomy. Furthermore, imaging factors, such as the CTSI score, number, location, and size of WON, were identified as predictors of necrosectomy. The combined model demonstrated superior discriminative ability (AUC = 0.892) compared with the individual parameters in the ROC analysis, suggesting that a complex interplay of multiple factors influences the need for DEN. The presence of early predictors could potentially inform the decision to implement immediate interventions in high-risk patients.

However, the timing of necrosectomy remains a matter of controversy. Several investigations on the management of WON advocate delayed drainage, and a similar protocol has been followed in necrosectomy, which is effective, safe, and associated with fewer necrosectomy sessions compared with other approaches. Delaying DEN allows tract maturation and alleviates the risk of complications. However, recent multicenter studies have examined the safety, feasibility, and benefits of immediate and early necrosectomy[20]. For instance, Yan et al[10] and Bang et al[21] showed that upfront endoscopic necrosectomy considerably reduced the number of reinterventions, improved the clinical outcomes, and shortened the length of hospitalization compared with the step-up approach, without increasing the adverse events. However, a recent multicenter study from Japan did not demonstrate the impact of necrosectomy timing on clinical success, which is consistent with the findings of our study[22]. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy advocates a tailored approach regarding the timing of DEN based on clinical signs, symptoms (including persistent SIRS and organ failure), and response to passive drainage[23]. Given the conflicting results on the timing of DEN administration and clinical outcomes, further multicenter RCTs are needed to establish the optimal timing.

In addition to the timing of necrosectomy, several studies have attempted to identify the predictors of necrosectomy. Factors such as WON size, the percentage and extent of necrosis, persistent organ failure, and multiple organ failure are associated with worse outcomes and the need for more aggressive interventions, as reported in the literature. One of the most critical predictors identified in our study and in the literature is the presence and extent of necrosis[24]. González-González et al[12] identified necrosis as the only factor predicting the need for necrosectomy, a finding similar to that of the present study. They found that necrosis increased the need for necrosectomy by 18% (OR = 1.18, 95%CI: 1.01-1.39), whereas in our study, necrosis was associated with an 8% increase (OR = 1.085, 95%CI: 1.026-1.148). Cosgrove et al[24] and Chandrasekhara et al[25] have also shown that an extensive collection and the presence of necrosis increase the need for necrosectomy. Studies have shown that necrosis exceeding 30%-50% significantly reduces the likelihood of clinical success with drainage alone and correlates with an increased need for DEN[13,14].

Several studies have reported that hypoalbuminemia is a predictor of persistent organ failure and infected pancreatic necrosis[14,26]. This condition is independently associated with both inflammation and compromised nutritional status in AP, which predisposes patients to extended hospital stays and increased mortality. In our study too, albumin level was identified as a predictor of necrosectomy. Similarly, paracolic gutter extension of the necrotic collection, a marker of an extensive disease burden, has been shown to compromise drainage efficacy and predict the need for repeated de

EUS-guided drainage using LAMS followed by selective DEN is a safe and effective strategy. Reported adverse events associated with necrosectomy include stent migration, infection, bleeding, and the development of pseudoaneurysms. Of these, stent migration is a known complication of LAMS, with reported rates ranging from 5% to 15%. Migration was slightly higher in our study, consistent with early placement in large necrotic cavities, which might have destabilized the stent. Walter et al[27] documented a 6% migration rate using LAMS, highlighting its reduced migration compared with plastic stents owing to its broad flanges and dumbbell shape. Considering other studies, Shah et al[8] and Siddiqui et al[7] detected migration rates of 3.5%-8%, with migration most commonly noted in collections > 12 cm or with paracolic extension. The bleeding rate in our cohort was 5.5%, which aligns with previous reports of 2%-8%, depending on the complexity of necrosis and the use of necrosectomy. Bang et al[21] observed a bleeding rate of 3% in 70 patients who had undergone necrosectomy, which was mostly controlled endoscopically. Although rare, pseudoaneurysm formation is a dreaded complication with a potentially fatal course, and its incidence increases in patients having large WON with multiple necrosectomy sessions. González-González et al[12] reported a pseudoaneurysm rate of 6.6%, which is com

Our study has several limitations, including its retrospective design and single-center data collection. Moreover, in this study, necrosectomy was performed based on symptoms and was not protocolized, which could lead to potential variability in the timing and technique of DEN. Numerous studies have demonstrated that protocolized necrosectomy leads to fewer reinterventions and complications[19]. With the introduction of new devices and an expanding therapeutic armamentarium, the endoscopic management of WON is evolving; however, these were not used in our study, and can be viewed as a limitation. Cavity irrigation with hydrogen peroxide has been shown to improve clinical success. Maharshi et al[28] conducted a randomized controlled trial comparing nasocystic irrigation with H2O2 alone vs the placement of biflanged metal stents in WON. This study found that adverse events, technical success, and clinical success were comparable, although the H2O2 group experienced longer procedure times and hospital stays. A multicenter study comparing DEN with and without hydrogen peroxide for WON showed that necrosectomy with H2O2 was linked to a higher clinical success rate (OR = 3.30, P = 0.033) and a quicker resolution (OR = 2.27, P < 0.001), without a significant increase in adverse events[29]. Similarly, an extensive pooled analysis of 186 patients reported a clinical success rate of 91.6% and low complication rates, supporting the safety and efficacy of this technique[30]. Newer devices, such as the Endo Rotor (Interscope Inc., United States), Over-the-Scope Grasper tools (Ovesco Endoscopy AG, Germany), flexible flanged LAMS, and waterjet-assisted necrosectomy systems, have emerged as promising adjuncts in the management of WON, aiming to improve clinical success rates and reduce procedural failure[6,31,32].

Despite these limitations, the study’s strength lies in its comprehensive analysis of the variables and their alignment with global trends. Future research should focus on developing predictive models that integrate radiological, clinical, and procedural variables to facilitate individualized therapies. Furthermore, large-scale, multicenter, randomized controlled trials are essential for standardizing the protocol for endoscopic interventions, identifying accurate pre-endoscopy predictors of reinterventions and complications, and exploring novel techniques and devices that enhance efficiency and improve both short-term and long-term outcomes of the procedure.

WON management remains challenging and warrants a multidisciplinary approach to improve patient outcomes. Advances in EUS-guided interventions over the past decade have positioned them at the forefront of managing WON. Endoscopic necrosectomy techniques and devices continue to evolve, and dedicated devices are expected to enhance efficacy and safety while improving the comfort of both patients and endoscopists. However, our understanding of the timing and necessity of necrosectomy must be improved. This study reinforces the predictive ability of various clinical, laboratory, and imaging factors - such as the presence of fever, SIRS, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, necrosis, and head of the pancreas WON - in identifying the need for necrosectomy in patients undergoing LAMS drainage for WON. Early recognition of these variables can help guide treatment planning, predict resource utilization, and augment clinical outcomes.

| 1. | Akshintala VS, Kamal A, Singh VK. Uncomplicated Acute Pancreatitis: Evidenced-Based Management Decisions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28:425-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chan KS, Shelat VG. Diagnosis, severity stratification and management of adult acute pancreatitis-current evidence and controversies. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:1179-1197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Beger HG, Rau BM. Severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical course and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5043-5051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4737] [Article Influence: 364.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (48)] |

| 5. | Kumar M, Sonika U, Sachdeva S, Dalal A, Narang P, Mahajan B, Singhal A, Srivastava S. Natural History of Asymptomatic Walled-off Necrosis in Patients With Acute Pancreatitis. Cureus. 2023;15:e34646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Saumoy M, Trindade AJ, Bhatt A, Bucobo JC, Chandrasekhara V, Copland AP, Han S, Kahn A, Krishnan K, Kumta NA, Law R, Obando JV, Parsi MA, Trikudanathan G, Yang J, Lichtenstein DR. Endoscopic therapies for walled-off necrosis. iGIE. 2023;2:226-239. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siddiqui A, Cangelosi MJ, Mumtaz T, Loren DE, Kowalski TE, Sharaiha RZ, Noor A, Iqbal U, Laine L. Su1300 Cost-Effectiveness of Fully Covered Self-Expanding Metal Stents, Lumen-Apposing Fully Covered Self-Expanding Metal Stents and Plastic Stents for Endoscopic Drainage of Pancreatic Walled-Off Necrosis in a Large Multicenter United States Study. Gastrointestl Endosc. 2017;85:AB324. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Shah RJ, Shah JN, Waxman I, Kowalski TE, Sanchez-Yague A, Nieto J, Brauer BC, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Safety and efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with lumen-apposing covered self-expanding metal stents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:747-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mukai S, Itoi T, Baron TH, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Kurihara T, Tsuchiya T, Ishii K, Tsuji S, Ikeuchi N, Tanaka R, Umeda J, Tonozuka R, Honjo M, Gotoda T, Moriyasu F, Yasuda I. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided placement of plastic vs. biflanged metal stents for therapy of walled-off necrosis: a retrospective single-center series. Endoscopy. 2015;47:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Yan L, Dargan A, Nieto J, Shariaha RZ, Binmoeller KF, Adler DG, DeSimone M, Berzin T, Swahney M, Draganov PV, Yang DJ, Diehl DL, Wang L, Ghulab A, Butt N, Siddiqui AA. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy at the time of transmural stent placement results in earlier resolution of complex walled-off pancreatic necrosis: Results from a large multicenter United States trial. Endosc Ultrasound. 2019;8:172-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Boermeester MA, Bollen TL, Bosscha K, Bouwense SA, Bruno MJ, Cappendijk VC, Consten EC, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, Erkelens WG, van Goor H, van Grevenstein WMU, Haveman JW, Hofker SH, Jansen JM, Laméris JS, van Lienden KP, Meijssen MA, Mulder CJ, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Poley JW, Quispel R, de Ridder RJ, Römkens TE, Scheepers JJ, Schepers NJ, Schwartz MP, Seerden T, Spanier BWM, Straathof JWA, Strijker M, Timmer R, Venneman NG, Vleggaar FP, Voermans RP, Witteman BJ, Gooszen HG, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2018;391:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 588] [Cited by in RCA: 513] [Article Influence: 64.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | González-González L, Bazaga S, Murzi M, Brujats A, Trias M, de Riba B, Romito R, Colán-Hernández J, Concepción M, Gordillo J, Pernas JC, Poca M, Soriano G, Guarner-Argente C. Predictors of the need for necrosectomy in patients with walled-off pancreatic necrosis treated with lumen apposition metal stents. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:1339-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhai YQ, Ryou M, Thompson CC. Predicting success of direct endoscopic necrosectomy with lumen-apposing metal stents for pancreatic walled-off necrosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96:522-529.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rana SS, Sharma V, Sharma R, Gupta R, Bhasin DK. Endoscopic ultrasound guided transmural drainage of walled off pancreatic necrosis using a "step - up" approach: A single centre experience. Pancreatology. 2017;17:203-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hammad T, Khan MA, Alastal Y, Lee W, Nawras A, Ismail MK, Kahaleh M. Efficacy and Safety of Lumen-Apposing Metal Stents in Management of Pancreatic Fluid Collections: Are They Better Than Plastic Stents? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63:289-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Willems P, Esmail E, Paquin S, Sahai A. Safety and efficacy of early versus late removal of LAMS for pancreatic fluid collections. Endosc Int Open. 2024;12:E317-E323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bang JY, Navaneethan U, Hasan MK, Sutton B, Hawes R, Varadarajulu S. Non-superiority of lumen-apposing metal stents over plastic stents for drainage of walled-off necrosis in a randomised trial. Gut. 2019;68:1200-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Vanek P, Falt P, Vitek P, Zoundjiekpon V, Horinkova M, Zapletalova J, Lovecek M, Urban O. EUS-guided transluminal drainage using lumen-apposing metal stents with or without coaxial plastic stents for treatment of walled-off necrotizing pancreatitis: a prospective bicentric randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023;97:1070-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baroud S, Chandrasekhara V, Storm AC, Law RJ, Vargas EJ, Levy MJ, Mahmoud T, Bazerbachi F, Bofill-Garcia A, Ghazi R, Maselli DB, Martin JA, Vege SS, Takahashi N, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Abu Dayyeh BK. A Protocolized Management of Walled-Off Necrosis (WON) Reduces Time to WON Resolution and Improves Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:2543-2550.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Albers D, Meining A, Hann A, Ayoub YK, Schumacher B. Direct endoscopic necrosectomy in infected pancreatic necrosis using lumen-apposing metal stents: Early intervention does not compromise outcome. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E490-E495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bang JY, Lakhtakia S, Thakkar S, Buxbaum JL, Waxman I, Sutton B, Memon SF, Singh S, Basha J, Singh A, Navaneethan U, Hawes RH, Wilcox CM, Varadarajulu S; United States Pancreatic Disease Study Group. Upfront endoscopic necrosectomy or step-up endoscopic approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis (DESTIN): a single-blinded, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;9:22-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tsujimae M, Saito T, Sakai A, Takenaka M, Omoto S, Hamada T, Ota S, Shiomi H, Takahashi S, Fujisawa T, Suda K, Matsubara S, Uemura S, Iwashita T, Yoshida K, Maruta A, Okuno M, Iwata K, Hayashi N, Mukai T, Yasuda I, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Masuda A; WONDERFUL study group in Japan. Necrosectomy and its timing in relation to clinical outcomes of EUS-guided treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis: a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2025;101:1174.e1-1174.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau JM, Albert J, Badaoui A, Bali MA, Barthet M, Besselink M, Deviere J, Oliveira Ferreira A, Gyökeres T, Hritz I, Hucl T, Milashka M, Papanikolaou IS, Poley JW, Seewald S, Vanbiervliet G, van Lienden K, van Santvoort H, Voermans R, Delhaye M, van Hooft J. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy. 2018;50:524-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cosgrove N, Shetty A, Mclean R, Vitta S, Faisal MF, Mahmood S, Early D, Mullady D, Das K, Lang G, Thai T, Syed T, Maple J, Jonnalagadda S, Andresen K, Hollander T, Kushnir V. Radiologic Predictors of Increased Number of Necrosectomies During Endoscopic Management of Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:457-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chandrasekhara V, Elhanafi S, Storm AC, Takahashi N, Lee NJ, Levy MJ, Kaura K, Wang L, Majumder S, Vege SS, Law RJ, Abu Dayyeh BK. Predicting the Need for Step-Up Therapy After EUS-Guided Drainage of Pancreatic Fluid Collections With Lumen-Apposing Metal Stents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:2192-2198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hong W, Lin S, Zippi M, Geng W, Stock S, Basharat Z, Cheng B, Pan J, Zhou M. Serum Albumin Is Independently Associated with Persistent Organ Failure in Acute Pancreatitis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2017:5297143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Walter D, Will U, Sanchez-Yague A, Brenke D, Hampe J, Wollny H, López-Jamar JM, Jechart G, Vilmann P, Gornals JB, Ullrich S, Fähndrich M, de Tejada AH, Junquera F, Gonzalez-Huix F, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP. A novel lumen-apposing metal stent for endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections: a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2015;47:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Maharshi S, Sharma SS, Ratra S, Sapra B, Sharma D. Management of walled-off necrosis with nasocystic irrigation with hydrogen peroxide versus biflanged metal stent: randomized controlled trial. Endosc Int Open. 2021;9:E1108-E1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Messallam AA, Adler DG, Shah RJ, Nieto JM, Moran R, Elmunzer BJ, Cosgrove N, Mullady D, Singh H, Cote G, Papachristou GI, Othman MO, Zhang C, Javaid H, Mercado M, Tsistrakis S, Kumta NA, Nagula S, Dimaio CJ, Birch MS, Taylor LJ, Labarre N, Han S, Hollander T, Keilin SA, Cai Q, Willingham FF. Direct Endoscopic Necrosectomy With and Without Hydrogen Peroxide for Walled-off Pancreatic Necrosis: A Multicenter Comparative Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:700-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mohan BP, Madhu D, Toy G, Chandan S, Khan SR, Kassab LL, Bilal M, Facciorusso A, Sandhu I, Adler DG. Hydrogen peroxide-assisted endoscopic necrosectomy of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;95:1060-1066.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ramai D, Ahmed Z, Chandan S, Facciorusso A, Deliwala SS, Alastal Y, Nawras A, Maida M, Barakat MT, Anderloni A, Adler DG. Safety and efficacy of the EndoRotor device for the treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis after EUS-guided cystenterostomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2024;13:165-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brand M, Bachmann J, Schlag C, Huegle U, Rahman I, Wedi E, Walter B, Möschler O, Sturm L, Meining A. Over-the-scope-grasper: A new tool for pancreatic necrosectomy and beyond - first multicenter experience. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:799-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/