Published online Jan 16, 2025. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v17.i1.102010

Revised: November 25, 2024

Accepted: December 27, 2024

Published online: January 16, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 4 Hours

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) serves an essential role in treating biliary diseases, especially in choledocholithiasis. However, due to the limited human lifespan, there remains a paucity of clinical investigations on ERCP treatment in patients over 90 years old.

To explore the effectiveness and safety of ERCP in super-older patients aged ≥ 90 years with choledochal stones.

This study retrospectively analyzed data from patients (aged ≥ 65 years) with choledocholithiasis who received ERCP treatment in our hospital from 2011 to 2023. Among them, patients ≥ 90 years old were in the super-older group, and patients aged 65-89 years were in the older group. Baseline data, including gender, number of stones, stone size, gallbladder stones, periampullary diverti

After matching, 44 patients were included in both the super-older group and the older group. The incidence of stroke in the super-older group was markedly higher than that in the older group [34.1% (15/44) vs 6.8% (3/44), P = 0.008]. The success rate of the ERCP procedure in the super-older group was 90.9% (40/44), compared to that in the older group [93.2% (41/44), P = 1.000]. Although endo

ERCP is safe and effective in super-older patients ≥ 90 years old with choledocholithiasis.

Core Tip: For the number of super-older patients with choledocholithiasis is small, only a few studies have investigated the therapeutic effects of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in such patients, which is insufficient in this rapidly aging world. The aim of this study was to compare the safety and efficacy of ERCP in patients aged 90 and older with patients aged 65-89 years by using a propensity score matching method to reduce bias. After matching, 44 patients were included in each group and our results showed no significant difference in the rates of successful ERCP procedures or complications between the two groups.

- Citation: Wang L, Li ZY, Wu F, Tan GQ, Wang BL. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients aged ninety and older with choledocholithiasis: A single-center experience in south China. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2025; 17(1): 102010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v17/i1/102010.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v17.i1.102010

According to the latest statistics report from the World Health Organization[1], with the general increase in human life expectancy, the number of older adults is growing year by year, especially in China[2]. Based on the redefinition of older adults by the Joint Committee of the Gerontological Society of Japan and the Japanese Geriatrics Society, individuals aged 65 to 74 are considered as pre-old, those aged 75 and above are regarded as old, and those aged 90 and above are classified as super-old[3]. In contrast, in China, individuals aged ≥ 65 years are generally considered older adults[4]. Given that cholelithiasis is a highly prevalent disease in China and that choledocholithiasis accounts for 10%-15% of cholelithiasis cases[5], the number of older patients with choledocholithiasis is substantial, with super-older individuals becoming increasingly common among them. Since the complication and mortality rate of choledochotomy in older patients with choledocholithiasis are higher compared to younger patients[6,7], endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is of great significance as a minimally invasive therapeutic modality with low complication and mortality rate for older patients with choledochotomy stones[8-10]. However, post-operative complications of ERCP, such as post-ERCP pancreatitis, hemorrhage, biliary tract infection, perforation, and intraoperative mesh basket entrapment, can still pose a serious impact on older patients, especially the super-older patients[11]. Although several studies have indicated that ERCP could be safely applied even in patients ≥ 90 years old[12,13] and may contribute to longer survival in these super-older patients[14,15], a recent multivariate analysis still identified age ≥ 90 years as a significant risk factor for adverse events during therapeutic ERCP[16]. Thus, it is highly necessary to make further evaluations of the effectiveness and safeness of ERCP for super-older patients with choledocholithiasis. However, research on this topic remains limited, particularly in south China.

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of the medical records of older patients diagnosed with choledochal stones, who were treated with ERCP in the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery in our hospital during the period from January 2011 to December 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Compliance with the diagnostic criteria for choledochal stones in the Chinese ERCP guideline (2018 edition)[17]; (2) Patients aged ≥ 65 years; (3) Receipt of ERCP treatment; (4) Presence of a normal gastrointestinal tract or undergoing Billroth I reconstruction; and (5) Availability of complete relevant clinical data. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients aged < 65 years; (2) Those not receiving ERCP treatment; (3) A history of Billroth II or Roux-en-Y gastrointestinal tract reconstruction; and (4) Incomplete clinical data. After filtering on the basis of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 428 patients aged ≥ 65 years qualified for the inclusion criteria. This cohort included 45 patients aged ≥ 90 years (super-older group) and 383 patients aged 65-89 years (older group). The patients were matched for baseline data on gender, number of stones, size of stones, gallbladder stones, peripapillary diverticulum, and successful choledochal intubation, and the two groups were compared for surgical success, stone retrieval rate, complication rate, and hospitalization duration. Ultimately, a total of 44 cases were incorporated into the super-older group, while an equal number of 44 cases were included in the older group. This study was approved by the ethics committee of Guangzhou Red Cross Hospital of Jinan University (approval No. 2024-249-01).

All patients were adequately informed about the procedure and provided their written informed consent prior to the operation. An electronic duodenoscope (TJF-260V, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and the main unit system (Evis-Exera II CLV-180, Olympus) were used in all procedures. ERCP was performed by two experienced endoscopists, each of whom had operated on more than 1000 ERCP procedures. All patients were classified in accordance with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status assessment before ERCP. Routine examinations included blood tests, two items of infection (procalcitonin and interleukin-6), liver function, renal function, coagulation function, markers of heart failure, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, cardiac ultrasound, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance/magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Patients were asked to fast for 6 to 12 hours before ERCP.

For patients with fair preoperative basal status who were able to tolerate surgery in the prone position, 10% lidocaine was administered for 15 minutes of surface anesthesia of the gastrointestinal tract. They were routinely injected with intramuscular pethidine hydrochloride injection (75 mg) for analgesia, intravenous diazepam injection (5-10 mg) for sedation, and resorcinol injection (40-80 mg) to inhibit duodenal peristalsis before the operation[18]. These medications were used to perform cholangiography. For patients with severe underlying diseases who could not tolerate a prone position or endoscopy after surface anesthesia and sedation or who strongly requested general anesthesia, general anesthesia was performed via endotracheal intubation. This was performed under the supervision of anesthesiologists after a preoperative evaluation by the anesthesiology department. During the procedure, cardiac monitoring and oxygenation were provided, and appropriate intravenous access was established.

Selective bile duct intubation was routinely performed using a disposable papillary sphincter arched dissector (Nanwei Medical Technology, Nanjing, China). After successful intubation, cholangiography was performed using a 30% pantethine-glucosamine (diluted in saline) contrast agent to determine the number, size, and location of the common bile duct stones. Depending on the patient’s preoperative use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications, the characteristics of the stones seen on intraoperative imaging, and the condition of the large duodenal papilla (size of the papilla and proximity to or involvement in a diverticulum), the decision was made to perform endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), endoscopic papillary balloon dilation (EPBD), or a combination of both. In general, for most patients, EST was the preferred choice. However, EPBD was used for patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy or those with an intradiverticular papilla or one very close to a diverticulum. For common bile duct stones > 1.0 cm, a combination of EST and EPBD was considered. For patients who had difficulty being intubated with an arched dissector, papillary pre-dissection using a needle dissector was attempted, followed by bile duct intubation. For choledochal stones < 1.0 cm in diameter, stones were extracted after EST using a stone extraction balloon, mesh basket, or both, usually in a single session. For stones > 1.0 cm in diameter, EST was combined with EPBD, and a lithotripsy mesh basket was used to break up the stones before extraction. If residual stones were observed on cholangiography, they were removed using a combination of techniques. In cases with a large number of stones that were difficult to remove at one time, poor patient tolerance, patients unable to lie prone for a long time, patients receiving antiplatelet or anticoagulant drugs before ERCP, or insufficient bridging time to perform an emergency ERCP, a nasobiliary drainage tube or a biliary stent was placed to temporarily alleviate the emergency. A subsequent procedure was scheduled to remove the stones. If the patient's vital signs became unstable during ERCP, the procedure was terminated immediately, and appropriate resuscitation was initiated. Patients exhibiting unstable vital signs following the procedure were relocated to the intensive care unit (ICU) for further management and treatment.

Postoperatively, routine interventions included cardiac monitoring, oxygen, fasting, fluid replacement, anti-infection, and omeprazole for acid control. Abdominal signs, nasal bile duct drainage flow and characteristics, and changes in vital signs were closely observed. Laboratory examinations such as blood routine, blood amylase, liver function, and infection markers were dynamically rechecked at 3-6 hours, 24 hours, and 48 hours after the procedure. If complications such as postoperative pancreatitis, bleeding, perforation, or infection occurred, timely and appropriate treatment was carried out according to the Chinese ERCP guidelines (2018 edition)[17].

Acute cholangitis refers to the diagnosis and grading of acute cholangitis in accordance with the 2018 edition of the Tokyo Guidelines[19]. Post-ERCP complications and management include the following items.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis: One of the most serious post-ERCP complications is pancreatitis. The widely accepted consensus definition of post-ERCP pancreatitis includes the following criteria: (1) Typical pancreatitis pain in the epigastrium (acute onset of persistent, epigastric pain); (2) Blood amylase level three times or more above the upper limit of normal value; and (3) Abdominal enhanced CT or magnetic resonance imaging showing typical pancreatitis. Post-ERCP pancreatitis is diagnosed when any two of the above three conditions are met[20]. After the occurrence of acute pancreatitis, standardized treatment is carried out according to the treatment guidelines, and the treatment is as follows: (1) Immediate fasting and water restriction to reduce the burden on the pancreas; (2) Active medication, such as inhibiting pancreatic enzyme secretion by using omeprazole sodium to reduce the progression of pancreatitis and antibiotics to prevent infection when necessary; (3) Timely imaging, including pancreas CT or magnetic resonance imaging, and other imaging tests to assess the severity and extent of pancreatitis; (4) Active supportive therapy to replenish water and electrolytes for maintaining stable blood circulation; and (5) Close monitoring of changes in vital signs.

Hyperamylasemia: Defined as a serum amylase level at least three times higher than the upper limit of the normal range without obvious clinical symptoms. Patients may be observed without specific treatment and dynamic rechecks of serum amylase levels to clarify disease progression.

Bleeding: Bleeding is identified by the presence of blood in vomit or black stools, a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of at least 2 g/L, or the need for a blood transfusion. Management depends on the severity of bleeding and specific circumstances: (1) Conservative treatment, such as appropriate rehydration and hemostatic drugs; (2) Re-endoscopic hemostatic treatment; (3) Interventional treatment; and (4) Surgical operation if endoscopic interventional treatments are ineffective in controlling the bleeding.

Perforation: Perforation is indicated by imaging evidence of retroperitoneal or gastrointestinal perforation. Risk factors for perforation during operation should be clarified intraoperatively, and prompt treatment - conservative, endoscopic, or surgical - should be initiated based on the specific situation.

Infection: Defined as elevated temperature (> 38 °C), leukocytosis, with or without abdominal pain. The management of post-ERCP infection involves many aspects, and the key treatments are as follows: (1) Pre-operative prophylactic anti-infective treatment; (2) Adequate post-operative biliary drainage, monitoring the biliary drainage closely, and intensifying the anti-infective treatment if necessary; (3) If the infection is uncontrollable, the infected lesion needs to be clarified in time, including re-surgery if required; and (4) Close monitoring and nursing care.

Stone removal, incomplete stone removal, and stone size: Stone removal was defined as no stones on final cholangiography. Incomplete stone removal was defined as successful biliary intubation but an inability to remove the stones completely. The size of the stones was determined by measuring the maximum diameter of the largest stone present, while stones that resembled biliary sediments were assigned a value of 0 if their diameter could not be accurately measured.

Successful ERCP procedure: Successful ERCP procedure was defined as stone extraction, successful biliary intubation, and successful retention of a nasociliary tube or placement of a biliary stent in the intended location.

Emergency ERCP: Emergency ERCP is defined as emergency biliary drainage in the diagnosis and classification of acute cholangitis in accordance with the 2018 edition of the Tokyo guidelines: Biliary drainage for relief of obstruction within 24 hours of admission to the hospital[19].

Recurrence: Recurrence was defined as readmission for choledocholithiasis during the study period after the prior removal of choledochal stones.

Rigorous statistical analysis was conducted to identify differences between the patient groups. The independent samples

After matching, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of overall underlying diseases and the proportion of patients with ≥ 2 underlying conditions. However, significantly more patients in the super-older group had a history of stroke compared to the older group (P = 0.008). The standardized mean difference of six controlled confounders between the two groups before and after matching are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, 43 patients (97.7%) in the super-older group were American Society of Anesthesiologists grade 3 or 4, a proportion significantly higher than the 17 patients (38.6%) in the older group (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences between the two groups in other aspects such as gender, bile duct and bile duct stone status, acute cholangitis status, peripapillary diverticulum, and gallbladder stones (Table 1).

| Baseline information | Before matching, case group (n = 45) | Before matching, control group (n = 383) | Before matching, P value | After matching, case group (n = 44) | After matching, control group (n = 44) | After matching, P value |

| Age1 | 92 (91, 94) | 78 (73, 83) | < 0.001 | 92 (91, 94) | 78.5 (72.25, 82) | < 0.001 |

| Sex, male/female | 14/31 | 185/198 | 0.029 | 14/30 | 16/28 | 0.688 |

| Emergency ERCP | 15 (33.3) | 105 (27.4) | 0.403 | 14 (31.8) | 13 (29.5) | 1.000 |

| Accompanying underlying disease | 37 (82.2) | 296 (77.3) | 0.451 | 36 (81.8) | 29 (65.9) | 0.189 |

| Hypertension | 30 (66.7) | 254 (66.3) | 0.963 | 29 (65.9) | 25 (56.8) | 0.523 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (11.1) | 94 (24.5) | 0.043 | 5 (11.4) | 7 (15.9) | 0.774 |

| Coronary heart disease | 15 (33.3) | 93 (24.3) | 0.186 | 15 (34.1) | 10 (22.7) | 0.332 |

| History of stroke | 16 (35.6) | 62 (16.2) | 0.001 | 15 (34.1) | 3 (6.8) | 0.008 |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 1 (2.2) | 7 (1.8) | 0.592 | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 2 underlying diseases | 21 (46.7) | 157 (41) | 0.465 | 20 (45.5) | 13 (29.5) | 0.189 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| History of malignant tumours of the biliopancreatic system | 2 (4.4) | 7 (1.8) | 0.242 | 2 (4.5) | 0 (0) | 0.500 |

| History of malignant tumours of the non-biliopancreatic system | 2 (4.4) | 37 (9.7) | 0.381 | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) | 1.000 |

| Intrahepatic bile duct stones | 8 (17.8) | 22 (5.7) | 0.007 | 8 (18.2) | 8 (18.2) | 1.000 |

| Asymptomatic choledocholithiasis | 3 (6.7) | 3 (0.8) | 0.017 | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 0.250 |

| Obstructive jaundice without cholangitis | 0 (0) | 16 (4.2) | 0.326 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1.000 |

| Choledochal stones without cholangitis | 4 (8.9) | 64 (16.7) | 0.175 | 4 (9.1) | 8 (18.2) | 0.344 |

| Pancreatitis | 10 (22.2) | 68 (17.8) | 0.463 | 10 (22.7) | 6 (13.6) | 0.388 |

| Gallbladder stones | 26 (57.8) | 270 (70.5) | 0.081 | 26 (59.1) | 23 (52.3) | 0.607 |

| Acute cholangitis | 41 (91.1) | 316 (82.5) | 0.142 | 40 (90.9) | 35 (79.5) | 0.227 |

| Mild cholangitis | 1 (2.2) | 67 (17.5) | 0.008 | 1 (2.3) | 5 (11.4) | 0.219 |

| Moderate cholangitis | 33 (73.3) | 211 (55.1) | 0.019 | 32 (72.7) | 27 (61.4) | 0.359 |

| Severe cholangitis | 7 (15.6) | 38 (9.9) | 0.364 | 7 (15.9) | 3 (6.8) | 0.344 |

| History of cholecystectomy | 6 (13.3) | 47 (12.3) | 0.838 | 6 (13.6) | 11 (25) | 0.267 |

| Anticoagulant or antiplatelet drug use | 12 (26.7) | 68 (17.8) | 0.147 | 12 (27.3) | 5 (11.4) | 0.092 |

| Number of stones1 | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.093 | 1.5 (1, 2.75) | 1 (1, 2) | 0.705 |

| Maximum stone diameter1 | 12 (8.5, 18) | 10 (5.7, 15) | 0.045 | 12 (8.25, 18) | 12 (9.25, 15) | 0.416 |

| Large stones (≥ 10 mm) | 32 (71.1) | 223 (58.2) | 0.096 | 31 (70.5) | 33 (75) | 0.804 |

| Multiple stones (≥ 2) | 23 (51.1) | 144 (37.6) | 0.079 | 22 (50) | 17 (38.6) | 0.441 |

| Multiple large stones | 17 (37.8) | 78 (20.4) | 0.008 | 16 (36.4) | 10 (22.7) | 0.180 |

| Largest diameter of common bile duct1 | 18 (14.5, 22) | 15 (12, 20) | 0.017 | 18 (14.25, 22) | 16 (14, 20.75) | 0.222 |

| Dilated common bile duct (≥ 10 mm) | 43 (95.6) | 349 (91.1) | 0.466 | 42 (95.5) | 44 (100) | 0.500 |

| Peripapillary diverticulum | 22 (48.9) | 161 (42) | 0.379 | 21 (47.7) | 18 (40.9) | 0.629 |

| ASA status rating (3 or 4) | 44 (97.8) | 212 (55.4) | < 0.001 | 43 (97.7) | 17 (38.6) | < 0.001 |

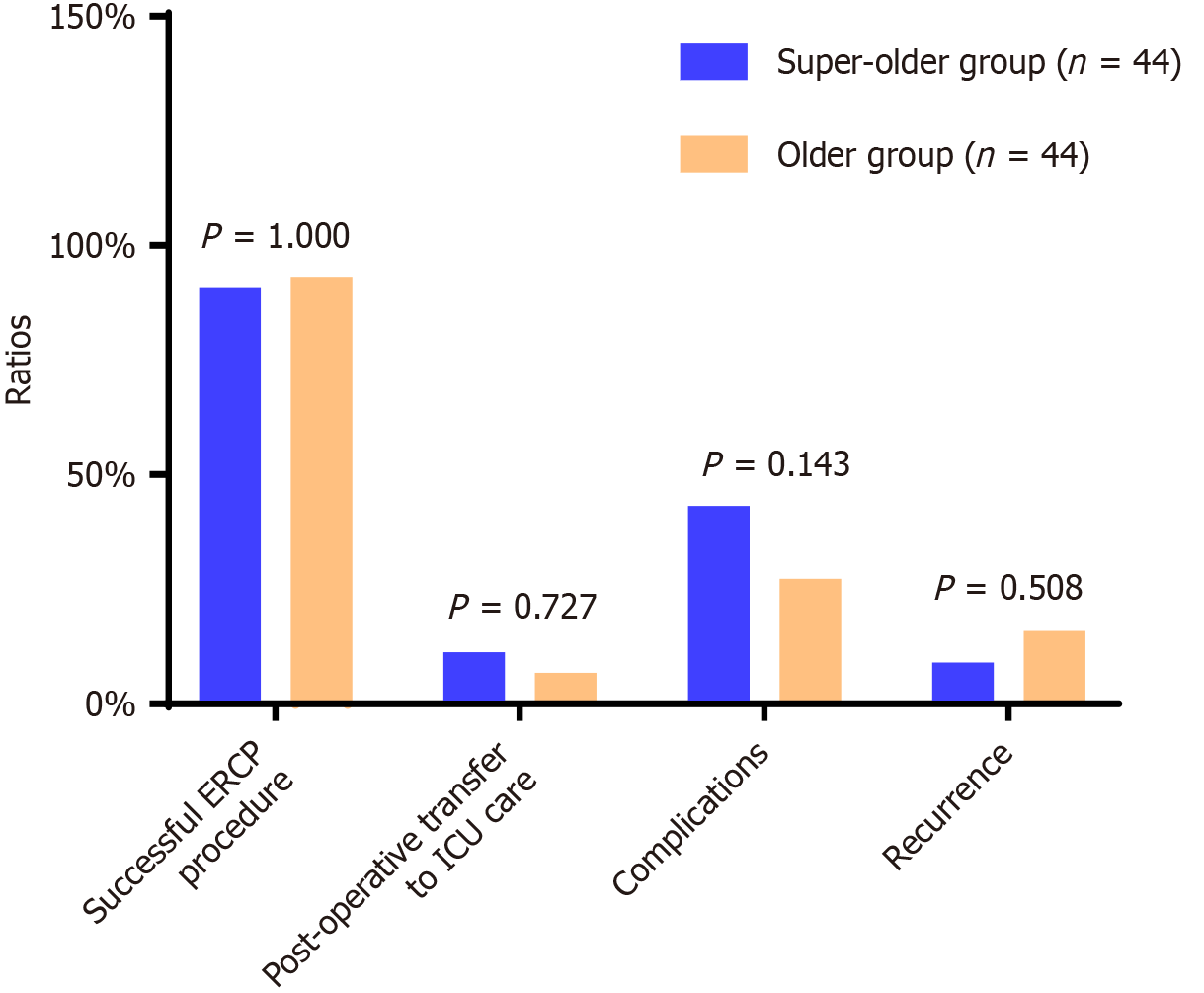

After matching, the ERCP procedure success rate and stone retrieval rate of patients in the super-older group were slightly lower than those in the older group. In addition, the proportion of patients in the super-older group who used tracheal intubation for general anesthesia and postoperative transfer to ICU care was higher than the older group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05, Figure 1). In comparison, the proportion of patients who used EPBD was significantly higher in the super-older group compared to the older group (P < 0.05, Table 2).

| Case group (n = 44) | Control group (n = 44) | P value | |

| Successful intubation | 41 (93.2) | 41 (93.2) | 1.000 |

| Stone removal | 29 (65.9) | 36 (81.8) | 0.118 |

| Incomplete stone removal | 12 (27.3) | 5 (11.4) | 0.092 |

| General anaesthesia | 4 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.125 |

| Laryngeal surface anaesthesia | 40 (90.9) | 44 (100) | 0.125 |

| Sphincter of Oddi preincision | 7 (15.9) | 6 (13.6) | 1.000 |

| Previous EST | 7 (15.9) | 11 (25) | 0.424 |

| Intraoperative EST | 31 (70.5) | 28 (63.6) | 0.629 |

| EPBD | 27 (61.4) | 8 (18.2) | < 0.001 |

| Mesh basket lithotripsy | 18 (40.9) | 19 (43.2) | 1.000 |

| Mechanical lithotripsy | 28 (63.6) | 26 (59.1) | 0.832 |

| ENBD | 38 (86.4) | 34 (77.3) | 0.424 |

| ERBD | 3 (6.8) | 2 (4.5) | 1.000 |

| The average times of ERCP procedures required for stone removal1 | 1.5 (1, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.204 |

| One ERCP for stone removal | 16 (36.4) | 16 (36.4) | 1.000 |

| Two ERCPs for stone removal | 11 (25) | 15 (34.1) | 0.503 |

| Three ERCPs for stone removal | 3 (6.8) | 5 (11.4) | 0.688 |

| Number of days in hospital1 | 15 (11.25, 23.75) | 14.5 (9.25, 20.75) | 0.815 |

After matching, there were no significant differences in the overall complication rate, mortality rate, and recurrence rate between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, the complication rate, infection rate, perforation rate, device embedment rate, and mortality rate were slightly higher in the super-older group compared to the older group (Table 3, Figure 1).

| Case group (n = 44) | Control group (n = 44) | P value | |

| Postoperative pancreatitis | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) | 1.000 |

| Hyperamylasemia | 8 (18.2) | 6 (13.6) | 0.727 |

| Infection | 5 (11.4) | 2 (4.5) | 0.375 |

| Bleeding | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.3) | 1.000 |

| Digestive tract perforation | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Heart failure | 2 (4.5) | 2 (4.5) | 1.000 |

| Cardiac infarction | 0 (0) | 2 (4.5) | 0.500 |

| Device entrapment | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Death | 3 (6.8) | 0 (0) | 0.250 |

Due to the scarcity of super-older patients, there is very limited research data on the effectiveness and safety of ERCP for the treatment of individuals with choledochal stones. Although complications related to biliopancreatic diseases have decreased with the iterative updating of medical technology, the associated surgical risks remain high for most older people with choledochal stones, especially the super-older. These patients often experience significantly deteriorated physical functions and are frequently accompanied by one or more underlying conditions, such as cerebrovascular or cardiovascular diseases or dementia[6,7]. The findings of this study indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between the super-older patients and older patients concerning the rates of successful ERCP procedures, stone extraction, complications, mortality, recurrence, and the duration of hospitalization. This indicates that ERCP is both effective and safe for treating choledocholithiasis in patients ≥ 90 years old.

Considering that non-ERCP treatments for choledocholithiasis are either associated with greater anesthetic risks - open choledochotomy and laparoscopic choledochotomy and exploration both require general anesthesia for routine endotracheal intubation and are significantly longer than ERCP treatments - or do not allow for the removal of stones and can only serve as a means of emergency biliary drainage (e.g., percutaneous hepatic puncture for choledochal duct drainage), or do allow for the removal of stones but require multiple stages of stone retrieval and a transabdominal wall fistula (e.g., percutaneous transhepatic choledochoscopic lithotripsy). It seems that ERCP may serve as a preferable treatment option for super-older patients with choledocholithiasis. However, this conclusion needs to be validated by a larger sample size of controlled clinical studies.

Several retrospective studies have investigated the efficacy and safety of ERCP in super-older patients. In terms of the effectiveness of ERCP, some of these previous studies report findings that differ slightly from the present study. A study by Saito et al[24] retrospectively compared the results of ERCP performed in 126 patients ≥ 90 years old with those of 569 patients (75-89 years) and showed that the rate of stone retrieval in super-older patients was significantly lower than in the younger patients (81% vs 94.9%, P < 0.001). In another study, Christoforidis et al[25] investigated the feasibility of therapeutic ERCP in 33 patients aged ≥ 90 years and 272 younger patients (75-89 years of age) with choledocholithiasis, where the stone clearance rate was only 24.2% in super-older patients but 90.8% in the non-super-older patients (P < 0.001). All of the above studies attributed the lower stone clearance rate in the super-older patients to the fact that these patients were more severely ill, in poorer physical condition, and had greater difficulty in stone clearance (more and larger bile duct stones). However, in terms of relieving biliary obstruction and keeping the bile duct open, there was no significant difference in the success rate of ERCP between the two age groups. In contrast, in the present study, although the success rates of ERCP procedures and the stone retrieval in the super-older patients were slightly inferior to those in the older group, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05), which differed from the results of the two studies mentioned above[24,25]. The reasons for this difference may be multifactorial. There may be potential differences in the demographic characteristics of different populations in different geographical areas. For individual patients, differences in the operator’s experience and the treatment process can also have an impact on the outcomes. More importantly, differences in research methodologies can directly influence study results. In the present study, we used the method of propensity score matching, which can reduce bias by controlling for relevant confounders. Although the rate of stone retrieval in the super-older patients was significantly lower than that in the younger patients before matching [64.4% (29/45) vs 81.5% (312/383), P = 0.007], which was in complete agreement with the results of Saito et al[24] and Christoforidis et al[25], there was no significant difference in the rate of stone retrieval between the two groups after matching, even in the average number of ERCPs required for stone removal. However, the studies by Saito et al[24] and Christoforidis et al[25] did not control for confounders, which may explain the discrepancy between their results and those of the present study.

The relationship between recurrence rate and stone size, gallbladder stones, post-cholecystectomy, and common bile duct diameter was also investigated in this study. The findings indicated that there was no significant difference in recurrence rate between the two groups of patients, although it was higher in the older group (15.9% vs 9.1%). The study by Jeon et al[26] concluded that a larger common bile duct diameter may be one of the preventive factors for stone recurrence and that it should be monitored dynamically after ERCP. Additionally, studies by Park et al[27] and Nakai et al[28] claimed that stone size, gallbladder stones, and post-cholecystectomy are also risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis. However, none of the above risk factors associated with recurrence were significantly different between the two groups of patients in the present study. Given the scarcity of studies on the recurrence of choledocholithiasis in super-older patients (potentially related to their limited life expectancy), the reasons for the recurrence in these patients need to be further analyzed.

Previous research has indicated that there is no significant difference in complication and mortality rates associated with ERCP in super-older patients compared to younger patients[29-32]. The present study’s findings align with this, as there were no significant differences in the complication and mortality rates between the two groups. However, these two rates were marginally elevated among the super-older patients. The slightly elevated complication rate observed in the super-older group may be attributed to a higher occurrence of hyperamylasemia and infections in this demographic compared with the older group. The former might be related to the fact that more patients in the super-older group had a history of stroke (which often required the use of antiplatelet agents) and, therefore, more EPBD, which is less likely to result in bleeding than EST but more likely to lead to hyperamylasemia or even pancreatitis[17], was used. This may be associated with the observation that patients within the super-older group presented a higher prevalence of comorbidities and exhibited a more deteriorated overall health status. Though there was no statistically significant difference in mortality rates observed between the two groups, all three deaths occurred in the super-older group. One patient died of sudden cardiac arrest after ERCP. One patient died of infectious shock due to a huge diverticular peripapillary papilla that prevented intubation. And one patient died of infectious shock due to a stone impaction in the middle of the common bile duct that prevented complete intubation. Previous literature reported that duodenal diverticula within 2-3 cm of the peripapillary diverticulum increases intubation difficulty[33,34]. The study by Chen et al[35] also concluded that peripapillary diverticula, stone incarceration in the common bile duct, and other reasons can lead to intubation difficulties or failure. Precision dissection or pancreatic duct occupancy can be considered to improve the success rate of intubation in such cases. We, therefore, speculate that although super-older age may not significantly increase mortality rates, the presence of conditions like peripapillary duodenal diverticula, stone incarceration, and other conditions that increase the difficulty of intubation, the mortality rate would still be higher due to their underlying diseases and poor physical conditions. This may render them unable to tolerate prolonged intubation or related procedures.

Regarding anesthesia for ERCP in super-older patients, previous research has yielded inconsistent findings. The study by Christoforidis et al[25] showed that there was no significant difference in the rate of using tracheal intubation general anesthesia between the super-older group and the non-super-older group. In contrast, Sugiyama et al[31] reported a significant difference in the rate of tracheal intubation general anesthesia utilization between the super-older and non-super-older groups (32% vs 4%, P < 0.001) and concluded that the super-older patients with critical conditions or inability to cooperate intraoperatively may require tracheal intubation general anesthesia to ensure safety. In the present study, there was no significant difference between the two groups in the rate of tracheal intubation general anesthesia utilization and postoperative transfer to ICU care, but the super-older group did account for a slightly higher percentage of both. This is consistent, to some extent, with the findings of Christoforidis et al[25] and Sugiyama et al[31]. Notably, the authors agree that tracheal intubation general anesthesia can better ensure the safety of some critically ill super-older patients because none of the four super-older patients who underwent general anesthesia with tracheal intubation in the present study had ERCP-related complications.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, this study is retrospective in nature. While PSM was employed to mitigate the influence of confounding variables, it offered merely a partial level of control. Second, this study spanned from 2011 to 2023, during which some case records were missing. This makes it difficult to exclude potential biases associated with the missing data. Finally, this study was conducted at a single center and involved a relatively limited sample size. To address these limitations, future multicenter prospective studies with larger participant cohorts are necessary.

Therapeutic ERCP is effective and safe in super-older patients ≥ 90 years old with choledocholithiasis and is likely to be a preferred treatment for these patients. However, its therapeutic value needs to be further evaluated in future studies.

We sincerely thank Senior Statistician Ling Chen for her statistical review of our manuscript.

| 1. | World Health Organization. World health statistics 2024: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. [cited 15 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240094703. |

| 2. | Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, Chen H, Chen X, Feng J, Feng Z, Glinskaya E, Gong J, Hu P, Kan H, Lei X, Liu X, Steptoe A, Wang G, Wang H, Wang H, Wang X, Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Wu J, Wu Z, Strauss J, Smith J, Zhao Y. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University-Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;400:1967-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 135.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ouchi Y, Rakugi H, Arai H, Akishita M, Ito H, Toba K, Kai I; Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological Society (JGLS) and Japan Geriatrics Society (JGS) on the definition and classification of the elderly. Redefining the elderly as aged 75 years and older: Proposal from the Joint Committee of Japan Gerontological Society and the Japan Geriatrics Society. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17:1045-1047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook 2024. [cited 15 August 2024]. Available from: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm. |

| 5. | Zhang ZM, Dong JH, Lin FC, Wang QS, Xu Z, He XD, Zhang C, Liu Z, Liu LM, Deng H, Yu HW, Wan BJ, Zhu MW, Yang HY, Song MM, Zhao Y. Current Status of Surgical Treatment of Biliary Diseases in Elderly Patients in China. Chin Med J (Engl). 2018;131:1873-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hacker KA, Schultz CC, Helling TS. Choledochotomy for calculous disease in the elderly. Am J Surg. 1990;160:610-2; discussion 613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhu J, Li G, Du P, Zhou X, Xiao W, Li Y. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with gallbladder and common bile duct stones: a meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:997-1005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iqbal U, Khara HS, Hu Y, Khan MA, Ovalle A, Siddique O, Sun H, Shellenberger MJ. Emergent versus urgent ERCP in acute cholangitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91:753-760.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Park CS, Jeong HS, Kim KB, Han JH, Chae HB, Youn SJ, Park SM. Urgent ERCP for acute cholangitis reduces mortality and hospital stay in elderly and very elderly patients. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2016;15:619-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siegel JH, Kasmin FE. Biliary tract diseases in the elderly: management and outcomes. Gut. 1997;41:433-435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee; Anderson MA, Fisher L, Jain R, Evans JA, Appalaneni V, Ben-Menachem T, Cash BD, Decker GA, Early DS, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Fukami N, Hwang JH, Ikenberry SO, Jue TL, Khan KM, Krinsky ML, Malpas PM, Maple JT, Sharaf RN, Shergill AK, Dominitz JA. Complications of ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:467-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Yun DY, Han J, Oh JS, Park KW, Shin IH, Kim HG. Is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography safe in patients 90 years of age and older? Gut Liver. 2014;8:552-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zhang DY, Zhai YQ, Zhang GJ, Chen SX, Wu L, Li MY. Safety and efficacy of therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients over 90 years of age. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2022;22:50-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sugimoto S, Hattori A, Maegawa Y, Nakamura H, Okuda N, Takeuchi T, Oyamada J, Kamei A, Kawabata H, Aoki M, Naota H. Long-term Outcomes of Therapeutic Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography for Choledocholithiasis in Patients ≥90 Years Old: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Intern Med. 2021;60:1989-1997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hu L, Sun X, Hao J, Xie T, Liu M, Xin L, Sun T, Liu M, Zou W, Ye B, Liu F, Wang D, Cao N, Liao Z, Li Z. Long-term follow-up of therapeutic ERCP in 78 patients aged 90 years or older. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Takahashi K, Tsuyuguchi T, Sugiyama H, Kumagai J, Nakamura M, Iino Y, Shingyoji A, Yamato M, Ohyama H, Kusakabe Y, Yasui S, Mikata R, Kato N. Risk factors of adverse events in endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for patients aged ≥85 years. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18:1038-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | ERCP group; Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopology; Biliopancreatic group, Chinese Association of Gastroenterologist and Hepatologist; National Clinical Research Center for Digestive Diseases. Chinese Guidelines for ERCP(2018). J Clin Hepatol. 2018;34:2537-2554. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Chinese Digestive Endoscopist Committee; Chinese Endoscopist Association; Chinese Physicians’ Association; Pancreatic Disease Committee, Chinese Physicians’ Association. Expert consensus on perioperative medication for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Clin Hepatol. 2018;34:2555-2562. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 484] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2084] [Article Influence: 59.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Chen JW, Maldonado DR, Kowalski BL, Miecznikowski KB, Kyin C, Gornbein JA, Domb BG. Best Practice Guidelines for Propensity Score Methods in Medical Research: Consideration on Theory, Implementation, and Reporting. A Review. Arthroscopy. 2022;38:632-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xu X, Wang MD, Xu JH, Fan ZQ, Diao YK, Chen Z, Jia HD, Liu FB, Zeng YY, Wang XM, Wu H, Qiu W, Li C, Pawlik TM, Lau WY, Shen F, Lv GY, Yang T. Adjuvant immunotherapy improves recurrence-free and overall survival following surgical resection for intermediate/advanced hepatocellular carcinoma a multicenter propensity matching analysis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1322233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cohen J. The t Test for Means. In: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 1988: 56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Saito H, Koga T, Sakaguchi M, Kadono Y, Kamikawa K, Urata A, Imamura H, Tada S, Kakuma T, Matsushita I. Safety and Efficacy of Endoscopic Removal of Common Bile Duct Stones in Elderly Patients ≥90 Years of Age. Intern Med. 2019;58:2125-2132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Christoforidis E, Vasiliadis K, Blouhos K, Tsalis K, Tsorlini E, Tsachalis T, Betsis D. Feasibility of therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for bile duct stones in nonagenarians: a single unit audit. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17:427-432. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Jeon J, Lim SU, Park CH, Jun CH, Park SY, Rew JS. Restoration of common bile duct diameter within 2 weeks after endoscopic stone retraction is a preventive factor for stone recurrence. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:251-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Park SY, Hong TH, Lee SK, Park IY, Kim TH, Kim SG. Recurrence of common bile duct stones following laparoscopic common bile duct exploration: a multicenter study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2019;26:578-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nakai Y, Isayama H, Tsujino T, Hamada T, Kogure H, Takahara N, Mohri D, Matsubara S, Yamamoto N, Tada M, Koike K. Cholecystectomy after endoscopic papillary balloon dilation for bile duct stones reduced late biliary complications: a propensity score-based cohort analysis. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:3014-3020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang XM, Hu B, Wang SZ, Pan YM, Gao DJ, Wang TT. [Safety and efficacy of therapeutic ERCP for patients over 90 years of age]. Xiandai Xiaohua Ji Jieru Zhenliao. 2013;18:132-134, 151. |

| 30. | Hui CK, Liu CL, Lai KC, Chan SC, Hu WH, Wong WM, Cheung WW, Ng M, Yuen MF, Chan AO, Lo CM, Fan ST, Wong BC. Outcome of emergency ERCP for acute cholangitis in patients 90 years of age and older. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1153-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile duct stones in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:187-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Katsinelos P, Paroutoglou G, Kountouras J, Zavos C, Beltsis A, Tzovaras G. Efficacy and safety of therapeutic ERCP in patients 90 years of age and older. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:417-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Liao WC, Angsuwatcharakon P, Isayama H, Dhir V, Devereaux B, Khor CJ, Ponnudurai R, Lakhtakia S, Lee DK, Ratanachu-Ek T, Yasuda I, Dy FT, Ho SH, Makmun D, Liang HL, Draganov PV, Rerknimitr R, Wang HP. International consensus recommendations for difficult biliary access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:295-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Christoforidis E, Goulimaris I, Kanellos I, Tsalis K, Dadoukis I. The role of juxtapapillary duodenal diverticula in biliary stone disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:543-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Chen FY, Chen SY. Evidence-Based Treatment for A Patient with Difficult Selective Biliary Cannulation during ERCP. Chin J Evid Based Med. 10:1345-1349. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/