Published online Aug 16, 2024. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v16.i8.494

Revised: July 2, 2024

Accepted: July 10, 2024

Published online: August 16, 2024

Processing time: 67 Days and 13.2 Hours

Heterotopic mesenteric ossification (HMO) is a clinically rare condition characterized by the formation of bone tissue in the mesentery. The worldwide reporting of such cases is limited to just over 70 instances in the medical literature. The etiology of HMO remains unclear, but the disease is possibly induced by mecha

We report the case of a 34-year-old male patient who presented with left lower abdominal pain following trauma to the left lower abdomen. He subsequently underwent surgical treatment, and the postoperative pathological diagnosis was HMO.

We believe that although there is limited literature and research on HMO, when patients with a history of trauma or surgery to the left lower abdomen present with corresponding imaging findings, clinicians should be vigilant in distinguishing this condition and promptly selecting appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions.

Core Tip: Due to the rarity of heterotopic mesenteric ossification (HMO), diagnosing this condition challenging. We report the case of a 34-year-old male who presented with left lower quadrant abdominal pain following left lower quadrant abdominal trauma, subsequently underwent laparoscopic resection for suspected bowel injury, and was ultimately diagnosed with HMO. We believe that although diagnosing HMO is challenging, the disease should be considered in patients with a history of trauma or surgery and corresponding imaging findings.

- Citation: Zhang BF, Liu J, Zhang S, Chen L, Lu JZ, Zhang MQ. Heterotopic mesenteric ossification caused by trauma: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 16(8): 494-499

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v16/i8/494.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v16.i8.494

Heterotopic mesenteric ossification (HMO) is a clinically rare condition characterized by the formation of osseous tissue within the mesentery[1]. The etiology of HMO remains unclear, but the disease is possibly induced by mechanical trauma, ischemia, or intra-abdominal infection, leading to the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts[2]. Here, we present a rare case of HMO in a 34-year-old male who recently experienced left lower quadrant abdominal trauma, presented with symptoms of left lower quadrant abdominal pain, underwent surgical intervention during hospitalization, and was postoperatively diagnosed with HMO.

A 34-year-old male presented with left lower quadrant abdominal pain persisting for over a month following left lower quadrant abdominal trauma. The patient’s pain was characterized as continuous and dull. He was subsequently admitted to our hospital.

The patient complained of left lower quadrant abdominal pain.

The patient had no previous medical history.

The patient’s personal and family history were unremarkable.

The patient’s vital signs at the time of arrival were as follows: Blood pressure, 118/90 mmHg; Heart rate, 75 beats/min; Respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and Body temperature, 36.4 °C. The abdominal physical examination revealed left lower quadrant tenderness, with identification of a palpable, poorly mobile, approximately 2-centimeter linear mass.

Routine blood, renal function, coagulation function, tumor marker, routine urine, and routine stool results revealed no abnormalities; C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates were within normal limits, and cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, and antituberculosis antibody results were all negative.

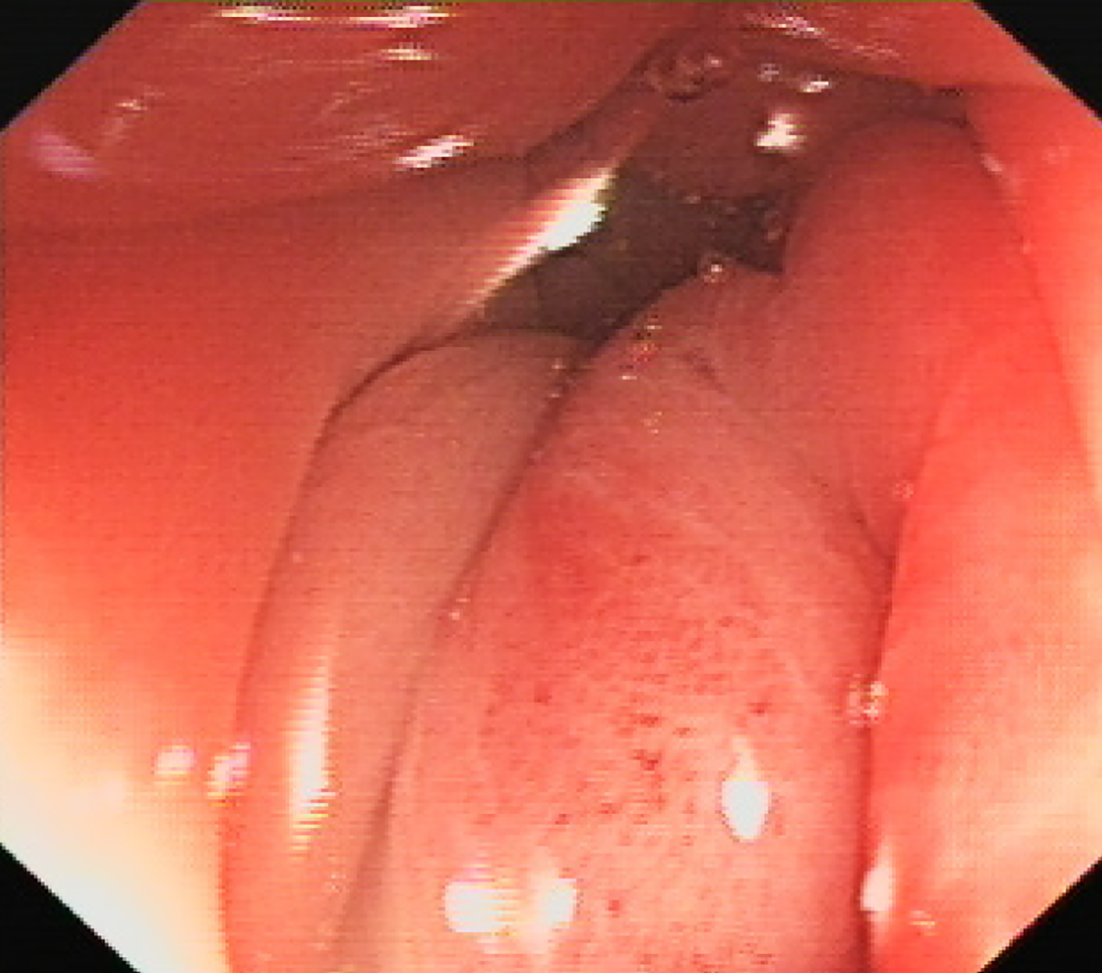

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed thickening of the left lower colon wall with pericolonic infiltration changes accompanied by calcification, measuring approximately 3.40 cm × 1.70 cm in cross-sectional size (Figure 1). The colonoscopy revealed stenosis in the sigmoid colon segment with highly congested and edematous mucosa, which was impassable with the standard colonoscope but could be traversed by an ultrathin endoscope, which revealed a stenotic segment approximately 1-centimeter in length (Figure 2).

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with HMO.

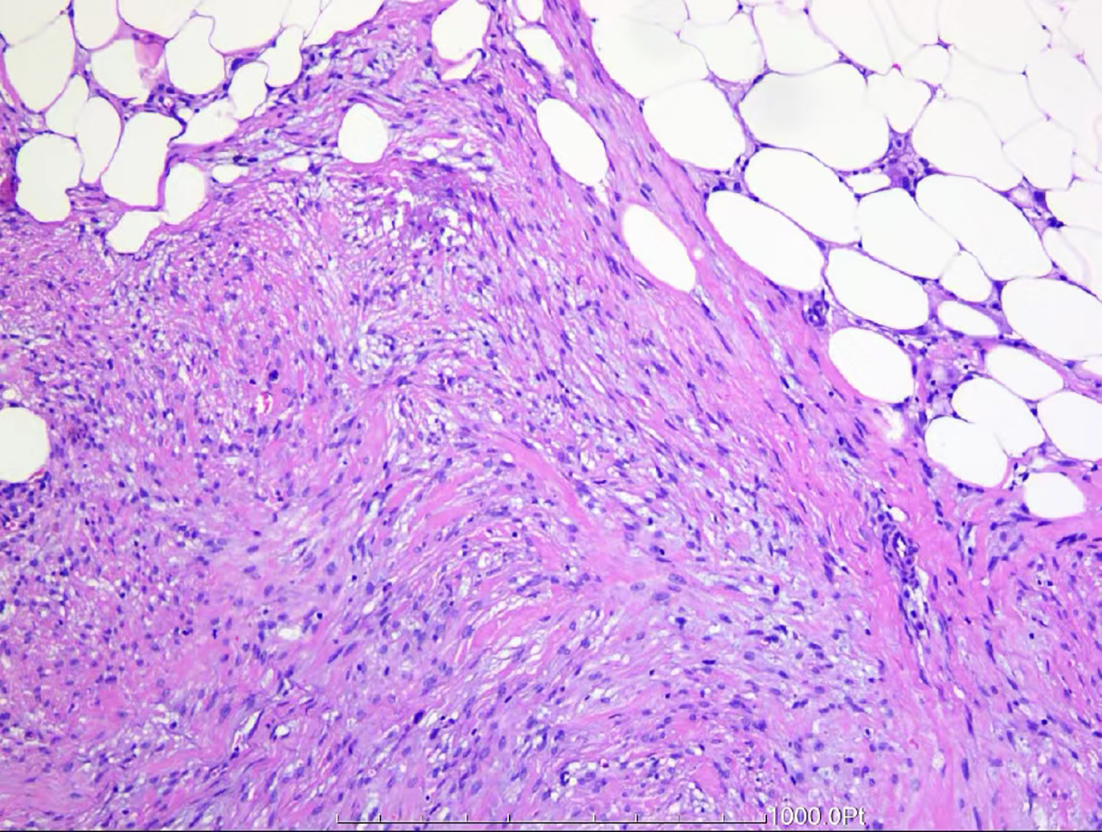

After admission and completion of relevant examinations, the cause of stenosis of the sigmoid colon in the patient remained unclear. The patient had a history of external force impact one month prior, and trauma-induced intestinal injury could not be ruled out. Laparoscopic radical sigmoid colon resection was suggested for definitive treatment. A preoperative preparation was completed to exclude surgical contraindications, and laparoscopic radical sigmoid colon resection was performed under general anesthesia. Intraoperatively, stenosis of the sigmoid colon segment was observed, measuring approximately 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm × 2.0 cm, with a hard texture, and enlarged lymph nodes were found at the root of the mesenteric vessels. Pathological examination revealed a smooth and folded mucosal surface on one side of the sigmoid colon, causing luminal stenosis. A hard area with unclear boundaries, measuring approximately 3.5 cm × 2.5 cm, was observed in the mesentery outside the intestinal wall. The cut surface was grayish yellow, with solid parts showing ossification. One lymph node measuring 0.2 cm in diameter was palpable in the mesentery outside the hard area of the intestinal wall, where spindle-shaped cells and fat cells were distributed in patches. The spindle-shaped cells were arranged in bundles or interwoven, were partially disordered, had short spindle-shaped nuclei, were slightly pointed at both ends, and had an eosinophilic cytoplasm; the area exhibited focal new bone formation and was diagnosed as mesenteric ectopic ossification (Figure 3).

The patient recovered smoothly after surgery, and no recurrence was observed at the one-year follow-up examination.

HMO refers to the formation of bone tissue within the mesentery, resulting in symptoms such as pain, local compression, or functional impairment in affected patients. The disease represents a rare type of heterotopic ossification. Since its initial designation in 1999[1], HMO (also known as mesenteric heterotopic ossification) has been documented in more than 50 published case reports worldwide; this condition predominantly affects males, with an average onset age of 48.38 ± 18.27 years[3]. Because HMO is rare, data are limited to case studies, and the specific pathogenesis remains unclear. One hypothesis is that HMO forms when periosteal or chondrogenic cells are implanted into the mesentery during surgery and develop into ectopic bone[4]. Another proposed theory suggests that mesenchymal stem cells within the abdominal cavity, when stimulated by mechanical trauma, ischemia, or intra-abdominal infection, activate genes regulating osteogenic or chondrogenic differentiation, which causes mesenchymal stem cells in the mesentery to differentiate into osteoblasts or chondrocytes, resulting in heterotopic ossification[5]. The clinical manifestations of this condition mainly include chronic abdominal pain, unexplained abdominal masses, gastrointestinal symptoms, and abdominal tenderness, among other signs and symptom. Additionally, some patients may remain asymptomatic and have the condition incidentally detected through imaging studies or during surgical procedures[3,6]. Owing to the rarity and low occurrence frequency of HMO worldwide, the diagnosis of this condition is highly challenging.

On abdominal CT examination, HMO presents as densely radiopaque areas surrounding the mesentery. However, malnutrition-related calcifications, bone tumors, contrast agent leakage, foreign bodies, or extraskeletal osteosarcoma may also present manifest similar clinical presentations, making differentiation from HMO challenging[7]. Although abdominal CT cannot be used to definitively diagnose HMO, three-dimensional CT reconstruction techniques can be used to precisely determine the location of HMO lesions and the spatial adjacency these lesions to the surrounding tissues[8]. This key finding can potentially guide implications for the formulation of surgical strategies to treat for HMO. Ultrasonography has been demonstrated to detect ectopic ossification more rapidly than traditional radiographic examinations[8]. Falsetti et al[9] proposed that typical ultrasound imaging for diagnosing ectopic ossification presents as a ring-like structure, characterized by central hypoechoic, peripheral hyperechoic areas, and surrounding soft tissues exhibiting hypoechoic features, with the hip region demonstrating the most pronounced manifestations. However, ultrasound examination for ectopic ossification diagnosis remains in the exploratory stage, with no studies having investigated the ultrasound diagnosis of HMO. Therefore, currently the only definitive diagnostic method is surgical resection of the affected intestinal segment followed by histopathological analysis[10].

The histopathological features of HMO are similar to those of myositis ossificans. The central lesion consists of spindle-shaped fibroblasts or myofibroblasts with a tendency to transition peripherally into bone-like tissue; mature bone trabeculae are visible peripherally, lined by osteoblasts; some cases also show deposition of cartilaginous tissue and calcium salts; within the lesion, adipose tissue is observed along with sparse infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells; focal necrosis may occur in parts of the adipose tissue, accompanied by a tissue reaction, and spindle-shaped fibroblasts or myofibroblasts show mild pleomorphism, with areas of increased cell density and occasional mitosis, although devoid of pathological mitoses or cytological features of neoplastic cells[1,11,12]. Therefore, HMO does not undergo malignant transformation, but this disease can lead to serious complications such as intestinal obstruction, enterocutaneous fistula, intestinal perforation, and sepsis, resulting in an increased mortality rate among patients with underlying conditions[3]. Currently, there is no established unified treatment regimen for HMO. Treatment methods mainly include conservative and surgical approaches. Conservative treatment primarily involves the use of anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications to alleviate pain and inflammatory responses. Additionally, some patients may require medications such as calcium and vitamin D to maintain balanced bone metabolism[10,13]. The prognosis of HMO is generally favorable, with no current evidence of its malignant potential. Conservative treatment should be pursued whenever possible to avoid surgery and prevent further ossification. However, conservative treatment is typically employed to control symptoms and alleviate pain, rather than to eliminate heterotopic ossification. Therefore, for patients with severe complications such as intestinal obstruction, intestinal fistula, or intestinal perforation, surgical resection of the affected area is the most effective treatment method[13,14].

The patient in this case is a young male who presented with left lower abdominal discomfort. Upon examination, a cord-like mass was found in his left lower abdomen. He had a history of trauma to the left lower abdomen one month prior to admission. After thorough examination, surgical intervention was performed, and the affected intestinal segment was resected. Pathological examination revealed spindle-shaped or intertwining arrangements of cells with focal new bone formation, which was consistent with the histopathological features of HMO, leading to the final diagnosis of HMO. Considering previously published literature, the patient’s sigmoid colon luminal narrowing and abdominal pain were attributed to mesenteric ossification secondary to traumatic injury. A review of the literature revealed that, among the globally reported cases of HMO, a minority present with abdominal pain or discomfort, with only a few cases manifes

In conclusion, despite the limited number of case reports and studies on HMO, clinicians should be vigilant in identifying this condition when dense calcifications are detected on abdominal CT scans, especially in patients with a history of abdominal trauma or surgery. Timely consideration and selection of appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic strategies are crucial for patient management.

| 1. | Wilson JD, Montague CJ, Salcuni P, Bordi C, Rosai J. Heterotopic mesenteric ossification ('intraabdominal myositis ossificans'): report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1464-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xu Y, Huang M, He W, He C, Chen K, Hou J, Huang M, Jiao Y, Liu R, Zou N, Liu L, Li C. Heterotopic Ossification: Clinical Features, Basic Researches, and Mechanical Stimulations. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:770931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Althaqafi RMM, Assiri SA, Aloufi RA, Althobaiti F, Althobaiti B, Al Adwani M. A case report and literature review of heterotopic mesenteric ossification. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2021;82:105905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Koolen PG, Schreinemacher MH, Peppelenbosch AG. Heterotopic ossifications in midline abdominal scars: a critical review of the literature. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2010;40:155-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bahmad HF, Lopez O, Sutherland T, Vinas M, Ben-David K, Howard L, Poppiti R, Alghamdi S. Heterotopic mesenteric ossification: a report of two cases. J Pathol Transl Med. 2022;56:294-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Andrea Aurelio R, Nicola R, Stefani C, Francesco S, Alberto F, Anna Vittoria M, Roberta G. An unusual case of bowel obstruction in emergency surgery: The heterotopic mesenteric ossification. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20926042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tonino BA, van der Meulen HG, Kuijpers KC, Mallens WM, van Gils AP. Heterotropic mesenteric ossification: a case report (2004:10b). Eur Radiol. 2005;15:195-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ranganathan K, Loder S, Agarwal S, Wong VW, Forsberg J, Davis TA, Wang S, James AW, Levi B. Heterotopic Ossification: Basic-Science Principles and Clinical Correlates. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1101-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Falsetti P, Acciai C, Carpinteri F, Palilla R, Lenzi L. Bedside ultrasonography of musculoskeletal complications in brain injured patients. J Ultrasound. 2010;13:134-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Torgersen Z, Osmolak A, Bikhchandani J, Forse AR. Ectopic bone in the abdominal cavity: a surgical nightmare. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1708-1711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hakim M, McCarthy EF. Heterotopic mesenteric ossification. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:260-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Honjo H, Kumagai Y, Ishiguro T, Imaizumi H, Ono T, Suzuki O, Ito T, Haga N, Kuwabara K, Sobajima J, Kumamoto K, Ishibashi K, Baba H, Sato O, Ishida H, Kuwano H. Heterotopic mesenteric ossification after a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurism: case report with a review of literatures. Int Surg. 2014;99:479-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zamolyi RQ, Souza P, Nascimento AG, Unni KK. Intraabdominal myositis ossificans: a report of 9 new cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hicks CW, Velopulos CG, Sacks JM. Mesenteric calcification following abdominal stab wound. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:476-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/