Published online Dec 16, 2024. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v16.i12.661

Revised: August 27, 2024

Accepted: November 6, 2024

Published online: December 16, 2024

Processing time: 185 Days and 9.1 Hours

Capsule endoscopy (CE) is a pivotal diagnostic tool for gastrointestinal (GI) dis

To investigate the use of a 72-hour extended patency protocol to improve func

We performed a prospective, open-label study evaluating an extended 72-hour protocol for confirming functional patency with the PC. Conducted over six months, 135 patients with risk factors for capsule retention were enrolled. The primary endpoint was the capsule retention rate in patients with confirmed func

Functional patency was confirmed in 48.9% (n = 66) of patients within 28 hours, with an additional 17.4% (n = 12) confirmed within 72 hours, increasing the overall patency rate to 57.8%. There was no significant difference in small bowel transit time between patients confirmed for patency at 28 hours vs those con

Extending the patency assessment protocol to 72 hours significantly improves the rate of confirmed functional patency without increasing the risk of capsule retention. This protocol is safe, effective, and cost-neutral, allowing more patients to benefit from CE. Further studies are recommended to refine the protocol and enhance its clinical utility.

Core Tip: Extending the patency capsule assessment window to 72 hours significantly increases the confirmed functional patency rate from 48.9% to 57.8% in high-risk patients undergoing capsule endoscopy (CE), without increasing the risk of capsule retention. This simple and cost-neutral modification can enhance patient care by reducing unnecessary exclusions from CE.

- Citation: O'Hara FJ, Costigan C, McNamara D. Extended 72-hour patency capsule protocol improves functional patency rates in high-risk patients undergoing capsule endoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 16(12): 661-667

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v16/i12/661.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v16.i12.661

Since being introduced into clinical practice in 2000, capsule endoscopy (CE) has established itself as an important diagnostic tool for investigating a wide variety of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases[1]. The most common indication is investigation of obscure GI bleeding, while diagnosis and assessment of small bowel Crohn’s disease, surveillance in polyposis syndromes, and evaluation of complex coeliac disease make up the majority of other indications[2].

CE is a comfortable, non-invasive procedure that is well-suited for outpatient settings. Adverse events are rare, with the most significant risk being the capsule getting retained within the GI tract. Capsule retention is defined as the detection of a capsule on abdominal radiological imaging 14 days or more after ingestion or when surgical removal is required due to small bowel obstruction[3]. While capsule retention is typically asymptomatic and the capsule can often pass naturally during follow-up without intervention, there remains a risk of bowel obstruction, which may necessitate surgery or endoscopic intervention for removal[4,5].

Risk factors associated with capsule retention have been well-characterised in the published literature[6]. The presence of a combination of symptoms suggestive of bowel obstruction (nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain and abdominal distension), previous small-bowel resection, abdominal/pelvic radiation therapy, and chronic high-dose non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) usage have all been shown to increase the risk of retention of the capsule[7-9].

The patency capsule (PC) is a dissolvable dummy capsule which was first introduced in 2005[10] due to deficiencies in radiological imaging techniques including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) to predict the functional patency of the GI tract during CE. CT is associated with a high radiation dose. In both modalities false−negative results may emerge in patients with obstruction, especially when this occurs intermittently or is “only” partial.

A recent meta-analysis reported a retention rate of 2.1% (95%CI: 1.5%-2.8%) for patients undergoing CE for suspected small bowel bleeding and 2.2% (95%CI: 0.9%-5.0%) for those evaluated due to abdominal pain and/or diarrhea[11]. In cases of suspected inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) retention was 3.6% (95%CI: 1.7%-8.6%), while in those with estab

The most extensive systematic review to date, conducted by Wang et al[6] and including 108079 CE procedures, repor

While CE after failed patency has been shown to have high retention rates. Capsule retention of 11.1% was observed in one study where 18 patients underwent CE after failing patency assessment, however 89%of subjects had an uneventful CE procedure and passed the capsule[12]. Previously published data by our group has also reported functional patency rates by PC of only 55.3%[12]. Thus, there is a risk that overuse of the PC will exclude patients unnecessarily from CE. Indeed, reflecting this ESGE does not recommend a patency assessment to all patients undergoing CE[3].

CE has become the gold standard diagnostic tool for various small bowel conditions. While it is important to be cautious, denying access to CE for a significant number of patients due to potentially false-positive patency tests could adversely affect patient care. Further research and the development of methods to improve the confirmation of functional patency without increasing the risk of capsule retention.

Previously published data from a single study has suggested that patient-reported passage of an intact capsule up to 72 hours post-ingestion was safe for confirmation of functional patency[13].

We performed a single-centre prospective open-label study over 6 months from January to July of 2023. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Joint Research Ethics Committee of Tallaght/St James Hospital. All patients over the age of 18 referred for CE who were deemed to have at least one risk factor for capsule retention at preassessment were enrolled. Risk factors for retention were previous abdominal surgery, known Crohn’s disease, long-term or high-dose NSAID use, known GI obstruction, previous capsule retention and obstructive symptoms[3]. Patients were consented prior to the procedure and advised of the protocol.

For functional patency assessment the Pillcam Patency Capsule (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) was used. This is the same shape and size as the Pillcam SB3 small bowel capsule but has a soluble body consisting of lactose-containing 10% barium sulphate covered with an impermeable film coating. Retention of the PC in the intestine is designed to result in complete disintegration of the capsule body, leaving behind only the impermeable film coating, which can pass through narrow stenotic areas. This occurs due to intestinal fluid entering the PC via timer plugs and the dissolution of the capsule. In the small bowel, this begins after approximately 33 hours post oral administration.

The PC was ingested with water on the morning of the assessment. No fasting was required before the procedure and no prokinetic medications were used as part of the protocol.

The definition of confirmed functional patency of the GI tract was that the PC passed out of the body intact within 28 hours. Patients who self-reported passage of an intact capsule in their stool by 28 hours post-ingestion were deemed to have functional patency. Those who didn’t report capsule passage had a plain film abdominal X-ray. If the PC was not observed on the X-ray at 28 hours the intact PC was considered to have been excreted from the body without the patient’s knowledge, confirming functional patency. Any individual with radiological evidence of a capsule remaining in the GI tract was deemed not to have functional patency. Of note any patients who reported symptoms consistent with transient obstruction during the patency test period were also deemed not to have functional luminal patency and were excluded.

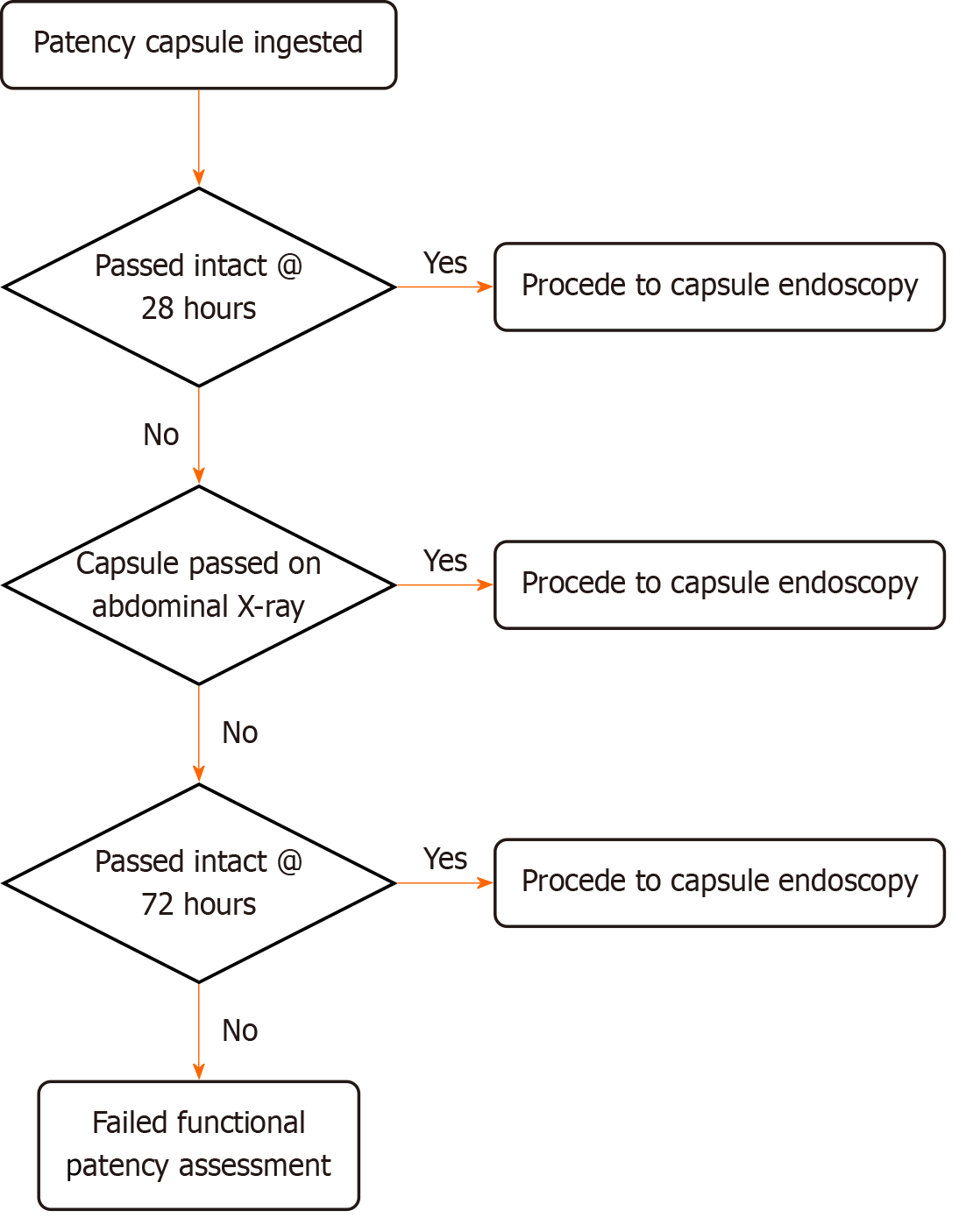

Patients without passage of the PC at 28 hours went into the extended patency arm of the study. These patients were contacted by phone 72 hours post-PC ingestion. Patients who confirmed passage of an intact capsule up to 72 hours post-ingestion were deemed as having confirmed functional patency and went forward for a CE (Figure 1).

Abdominal ultrasound, tomosynthesis, and CT were not used to assess the PC location in this study.

The primary endpoint was the capsule retention rate in patients who had confirmed functional patency by PC. Secondary endpoints were the rates of confirmed functional patency and by what means (self-reported or via radiology) small bowel transit time on follow-up capsules and adverse events were also recorded.

The results are reported using descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range) for patient characteristics. Compari

One hundred and thirty-five patients who underwent patency assessment before CE over 6 months from January to July 2023 were enrolled in the study. Of this group, 75 were female (56%) with a mean age of 50.1 years (Table 1). The indica

| Study population demographics | n = 135 |

| Male, n (%) | 60 (44) |

| female, n (%) | 75 (56) |

| Age, year (IQR) | 50.1 (29.0) |

| Indication for capsule endoscopy | |

| Suspected Crohn's disease, n (%) | 67 (49.7) |

| Crohn's assessment, n (%) | 30 (22.5) |

| IDA, n (%) | 24 (17.7) |

| GI bleeding, n (%) | 3 (2.4) |

| Other, n (%) | 10 (6.5) |

Indications for patency assessment included surgery in 31.9%, history of Crohn’s disease in 23.7%, NSAIDs in 13.3%, and Radiological findings in 13.3% (Table 2).

| Overall group, n = 135 | Extended patency group, n = 69 | P value | |

| Previous surgery | 43 (31.9) | 24 (34.8) | 0.7686 |

| Crohn’s disease | 32 (23.7) | 15 (21.7) | 0.8651 |

| Radiology | 18(13.3) | 10 (14.5) | 0.8344 |

| NSAIDs | 18 (13.3) | 8 (11.6) | 0.8286 |

| Endoscopic findings | 9 (6.7) | 5 (7.2) | - |

| Obstructive symptoms | 9 (6.7) | 4 (5.8) | - |

| Prior abdominal radiation | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.4) | - |

| No clear indication | 3 (2.2) | 2 (2.9) | - |

Of the 135 patients referred for patency assessment functional patency was confirmed in 66 (48.9%) patients at 28 hours. Of these, 23 patients reported passage of intact capsule within 28 hours while a further 43 patients had functional patency confirmed via abdominal X-ray.

Sixty-nine patients had radiological evidence of the PC on abdominal X-ray at 28 hours and went on to assessment at 72 hours. There was no statistically significant difference in age (50.6 vs 49.5, P = 0.7527) or sex characteristics (46.8% vs 54.6% female, P = 0.3913) between those who did and those who did not have confirmed patency at 28 hours using our standard protocol. There was also no statistical difference in indication for patency in the extended patency group in comparison to the overall cohort (Table 2).

At 72 hours a further 12 (17%) of 69 patients confirmed passage of an intact PC and were deemed to have functional patency by the study protocol. The extended protocol increased the overall confirmed functional patency rate from 48.9% (n = 66) to 57.8% (n = 78) of patients from the cohort of 135 patients. A further 3 patients reported passage of a damaged capsule up to 72 hours and were deemed to not to have confirmed functional patency by the study protocol.

In all 50.0% (n = 39/78) of patients who had a CE had clinically significant findings (Table 3). Enteritis/Ileitis, seen in 34.6% of studies (n = 27), was the most frequent finding.

| Items | n (%) |

| Normal study | 39 (50.0) |

| Enteritis/ileitis | 27 (34.6) |

| Angiodysplasia | 2 (2.6) |

| Duodenitis | 3 (3.8) |

| Small bowel polyp | 2 (2.6) |

| Colonic polyp | 2 (2.6) |

| Submucosal bulge | 1 (1.3) |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | 1 (1.3) |

| Gastric retention | 1 (1.3) |

There was a mean small bowel transit time of 241 minutes. There was no significant difference in transit time between those who passed patency before 28 hours and those who passed patency up to 72 hours [241 minutes vs 243 minutes (P = 0.9637); Table 4].

| n | SBTT (mean, minute) | SD | |

| Patency at 28 hours | 66 | 241 | 145 |

| Patency at 72 hours | 12 | 243 | 102 |

There was no capsule retention in patients who had confirmed functional patency in the standard or extended patency protocol.

Of interest, however, there was one retained capsule in a patient who had a failed patency assessment by standard protocol but went on to have a normal MRI small bowel and was deemed appropriate for CE. The capsule was retained in an area of ulcerated small bowel mucosa. The patient had an asymptomatic passage of the capsule by the time of an abdominal X-ray 6 weeks post-procedure. A small bowel lymphoma was diagnosed at a follow-up enteroscopy.

Abdominal pain and bloating was experienced by two patients (1.2%) who underwent patency assessment. Both had passed the capsule on abdominal X-ray at 28 hours post ingestion but were excluded from CE and were referred for alternative small bowel investigations. One patient had a history of known small bowel Crohn’s disease being assessed for active disease, which was confirmed on subsequent MRI small bowel. The second patient was under investigation for iron deficiency anaemia and had a normal antegrade enteroscopy subsequently.

PCs are a safe means of confirming functional patency prior to CE and to reduce the risk of capsule retention significantly[10]. Our retrospective data has shown that while the PC reduces the risk of capsule retention, there is likely a cohort of patients who fail functional patency assessment due to the nature of the test[12]. In high-volume CE centres, the availa

In our unit, radiological localization of the PC for patients who do not report passing it within 28 hours is usually performed only with plain film X-ray. With the established difficulty in accurately identifying the capsule location by X-ray, any visualized capsule is considered a failure, with no functional patency confirmed. Our retrospective data has shown a high failed patency assessment by this criterion of 43.1%[12]. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis reported failure rates for functional patency assessment ranging from 21.4% to 44%[15].

This prospective study has shown that of the 69 patients who failed patency assessment at 28 hours, 12 (17.4%) went on to have functional patency confirmed by the extended protocol and went on to have CE without capsule retention. This improved the overall functional patency rate from 48.9% to 57.8% without an increase in risk, as all subsequently passed the capsule. Thus, the extended patency protocol can allow us to conduct CE safely and effectively in patients without increasing the risk of capsule retention.

The previous study using an extended window to 72 hours showed that 6 of 19 patients (31.6%) in whom patency was not confirmed at 30 hours, had confirmed patency within 72 hours. No capsule retention occurred in these patients[13]. This was a higher rate again than achieved in our study.

This present study has several limitations. The subjects were consecutive patients in clinical practice at a single referral centre. The number of patients having capsules post-extended patency was small and requires ongoing monitoring for retention risk. The request for patients to examine their stool for the capsule was based on gross visual inspection only. More thorough stool inspection measures may have further increased the rate of confirmed functional patency but may not be acceptable to patients. Also, we depended on the patient to report accurately whether the capsule was passed intact or not. Based on low subsequent retention rates in our cohort, future assessment with a digital image would appear not to be necessary. No data was available at the time of analysis of outcomes for those patients who failed patency assessment and didn’t proceed to CE.

While this protocol improves overall functional patency rates by 17.4%, further investigation is needed to reduce the false positive rate further. Consideration for those patients who fail a patency assessment also warrants further study. The decision of whether further radiological imaging is required or proceeding directly to enteroscopy is currently an ad hoc decision in our unit. Those patients from external centres are returned to their treating physician.

The PC significantly reduces the retention risk in those with risk factors in CE. It is recognized as the safest assessment method in high-risk cohorts compared to other radiological techniques. However, it remains an imperfect measure of functional patency before CE, with a high exclusion rate for CE. Extended patency assessments up to 72 hours by this protocol has improved the functional patency rate in our cohort without increasing the risk of capsule retention in an easy-to-implement and cost-neutral manner. Taken together with the Japanese data, the safety to date suggests we should adopt this protocol with an ongoing audit of outcomes.

| 1. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1410] [Article Influence: 54.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Pennazio M, Spada C, Eliakim R, Keuchel M, May A, Mulder CJ, Rondonotti E, Adler SN, Albert J, Baltes P, Barbaro F, Cellier C, Charton JP, Delvaux M, Despott EJ, Domagk D, Klein A, McAlindon M, Rosa B, Rowse G, Sanders DS, Saurin JC, Sidhu R, Dumonceau JM, Hassan C, Gralnek IM. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:352-376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 52.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Rondonotti E, Spada C, Adler S, May A, Despott EJ, Koulaouzidis A, Panter S, Domagk D, Fernandez-Urien I, Rahmi G, Riccioni ME, van Hooft JE, Hassan C, Pennazio M. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy and device-assisted enteroscopy for diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel disorders: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Technical Review. Endoscopy. 2018;50:423-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 304] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rondonotti E. Capsule retention: prevention, diagnosis and management. Ann Transl Med. 2017;5:198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fernández-Urién I, Carretero C, González B, Pons V, Caunedo Á, Valle J, Redondo-Cerezo E, López-Higueras A, Valdés M, Menchen P, Fernández P, Muñoz-Navas M, Jiménez J, Herrerías JM. Incidence, clinical outcomes, and therapeutic approaches of capsule endoscopy-related adverse events in a large study population. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:745-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang YC, Pan J, Liu YW, Sun FY, Qian YY, Jiang X, Zou WB, Xia J, Jiang B, Ru N, Zhu JH, Linghu EQ, Li ZS, Liao Z. Adverse events of video capsule endoscopy over the past two decades: a systematic review and proportion meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2020;20:364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Postgate AJ, Burling D, Gupta A, Fitzpatrick A, Fraser C. Safety, reliability and limitations of the given patency capsule in patients at risk of capsule retention: a 3-year technical review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2732-2738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rondonotti E, Soncini M, Girelli C, Ballardini G, Bianchi G, Brunati S, Centenara L, Cesari P, Cortelezzi C, Curioni S, Gozzini C, Gullotta R, Lazzaroni M, Maino M, Mandelli G, Mantovani N, Morandi E, Pansoni C, Piubello W, Putignano R, Schalling R, Tatarella M, Villa F, Vitagliano P, Russo A, Conte D, Masci E, de Franchis R; AIGO, SIED and SIGE Lombardia. Small bowel capsule endoscopy in clinical practice: a multicenter 7-year survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1380-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Liao Z, Gao R, Xu C, Li ZS. Indications and detection, completion, and retention rates of small-bowel capsule endoscopy: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:280-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 561] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 30.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Spada C, Spera G, Riccioni M, Biancone L, Petruzziello L, Tringali A, Familiari P, Marchese M, Onder G, Mutignani M, Perri V, Petruzziello C, Pallone F, Costamagna G. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting functional patency of the small bowel: the Given patency capsule. Endoscopy. 2005;37:793-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rezapour M, Amadi C, Gerson LB. Retention associated with video capsule endoscopy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1157-1168.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | O'Hara F, Walker C, McNamara D. Patency testing improves capsule retention rates but at what cost? A retrospective look at patency testing. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1046155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Watanabe K, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Fujiwara Y. A Prospective Study Evaluating the Clinical Utility of the Tag-Less Patency Capsule with Extended Time for Confirming Functional Patency. Digestion. 2021;102:180-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nakamura M, Watanabe K, Ohmiya N, Hirai F, Omori T, Tokuhara D, Nakaji K, Nouda S, Esaki M, Sameshima Y, Goto H, Terano A, Tajiri H, Matsui T; J-POP study group. Tag-less patency capsule for suspected small bowel stenosis: Nationwide multicenter prospective study in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2021;33:151-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mitselos IV, Katsanos K, Tsianos EV, Eliakim R, Christodoulou D. Clinical Use of Patency Capsule: A Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2339-2347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/