Published online Jan 16, 2024. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v16.i1.44

Peer-review started: October 16, 2023

First decision: November 9, 2023

Revised: November 20, 2023

Accepted: December 7, 2023

Article in press: December 7, 2023

Published online: January 16, 2024

Processing time: 90 Days and 14.7 Hours

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is defined as bleeding that occurs proximal to the ligament of Treitz and can sometimes lead to potentially serious and life-threatening clinical situations in children. Globally, the cause of UGIB differs significantly depending on the geographic location, patient population and presence of comorbid conditions.

To observe endoscopic findings of UGIB in children at a tertiary care center of Bangladesh.

This retrospective study was carried out in the department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of Bangabandhu Shiekh Mujib Medical University, a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh, between January 2017 and January 2019. Data collected from hospital records of 100 children who were 16 years of age or younger, came with hematemesis, melena or both hematemesis and melena. All patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (Olympus CV 1000 upper gastrointestinal video endoscope) after initial stabilization. Necessary investigations to diagnose portal hypertension and chronic liver disease with underlying causes for management purposes were also done.

A total of 100 patients were studied. UGIB was common in the age group 5-10 years (42%), followed by above 10 years (37%). Hematemesis was the most common presenting symptom (75%) followed by both hematemesis and melena (25%). UGIB from ruptured esophageal varices was the most common cause (65%) on UGI endoscopy followed by gastric erosion (5%) and prolapsed gastropathy (2%). We observed that 23% of children were normal after endoscopic examination.

Ruptured esophageal varices were the most common cause of UGIB in children in Bangladesh. Other causes included gastric erosions and prolapsed gastropathy syndrome.

Core Tip: Various etiologies are responsible for upper gastrointestinal bleeding. However, we found a wide range of etiologies including non-gastrointestinal causes in Bangladeshi children.

- Citation: Mazumder MW, Benzamin M. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Bangladeshi children: Analysis of 100 cases. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2024; 16(1): 44-50

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v16/i1/44.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v16.i1.44

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is not uncommon in children. When the source of bleeding is proximal to the ligament of Treitz, it is defined as upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) and when distal to the ligament of Treitz as lower gastrointestinal bleeding[1]. UGIB varies greatly in presentation and may provoke anxiety in the child, caregivers and healthcare providers. UGIB presents commonly as hematemesis, melena or both hematemesis and melena. Hematemesis is defined as vomiting of blood that may be bright red or coffee-ground color, small or large volume and may be associated with clots. A fistful of clots is nearly equivalent to 500 mL of blood[2]. Melena is black, tarry stool, and 60 mL of blood is the minimum quantity to produce melena. Blood is present for at least 6 h in the intestine[3]. UGIB is infrequent in children with an estimated incidence of 1-2/10000 per year[4], where the majority are self-limiting[5]. Significant UGIB is infrequent and remains a management challenge to clinicians.

Etiology of UGIB in children is diverse, and causes vary by age, geographical location and associated comorbidities[6,7]. In older children and adolescents, significant causes of UGIB include variceal bleeding and peptic ulcer disease. Foreign body ingestion is rare in older children and adolescents. Common etiologies in infants are Mallory-Weiss tear and reflux esophagitis. Other common causes in neonates include swallowed maternal blood and milk protein allergy[7].

Management of patients with UGIB depends on an underlying cause, severity of bleeding and hemodynamic status of patient. There is a paucity of data regarding the etiology, mode of presentation and endoscopic findings of UGIB in children of Bangladesh. The purpose of the study was to observe endoscopic findings of 100 cases of UGIB admitted in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh.

This retrospective observational study was carried out in the department of Pediatric Gastroenterology of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University of Bangladesh. Data were collected from hospital records after approval from the departmental ethical committee. In total, 100 children who were 16 years of age or younger presented with hematemesis and/or melaena and underwent upper GI endoscopy after stabilization of vitals within 24-48 h. Patients who underwent sedation by parenteral midazolam and pethidine with preparations for resuscitation were included in this series. Patients who were older than 16 years of age or presented with bright red per rectal bleeding were excluded. Upper GI endoscopy was completed by an expert pediatric gastroenterologist of the same department with an Olympus CV 100 video endoscope model. All patients were treated according to the standard departmental protocol. Blood for grouping (ABO and Rh), routine complete blood count, and in selected cases blood liver biochemistry (alanine transaminase, serum albumin, prothrombin time) with Wilson’s disease/autoimmune hepatitis panel were done. Stool for occult blood, along with Doppler ultrasonography of the abdomen for ascites, liver echotexture, portal vein thrombosis/cavernous malformation, diameter/pressure and splenomegaly were completed for all patients according to the departmental protocol. The study was approved by the departmental Ethics Committee. Statistical analyses were performed using frequency, means, standard deviations and proportions.

A total of 100 children underwent UGI endoscopic evaluation during the study period. Among them, 62 were male (62%), and 38 (38%) were female. The mean age of the patients was 9 ± 4.25 years. Altogether, 22% of patients were younger than 5-years-old, 42% of patients were between 5-years-old and 10-years-old, and 36% of patients were above 10-years-old (Table 1). We observed that 15% of patients were admitted with impending shock (hypotension, tachycardia, cold clammy skin) from hematemesis and/or melena and needed volume resuscitation. Among the studied patients, 30 presented with isolated hematemesis, 2 presented with isolated melaena, and 68 presented with combined hematemesis and melaena (Table 1).

| Variable | Value |

| Age in yr | |

| < 5 | 22 (22) |

| 5-10 | 42 (42) |

| > 10 | 36 (36) |

| Mean ± standard deviation | 9.0 ± 4.5 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 62 (62) |

| Female | 38 (38) |

| Presentation | |

| Hematemesis | 30 (30) |

| Melena | 2 (2) |

| Hematemesis and melena | 68 (68) |

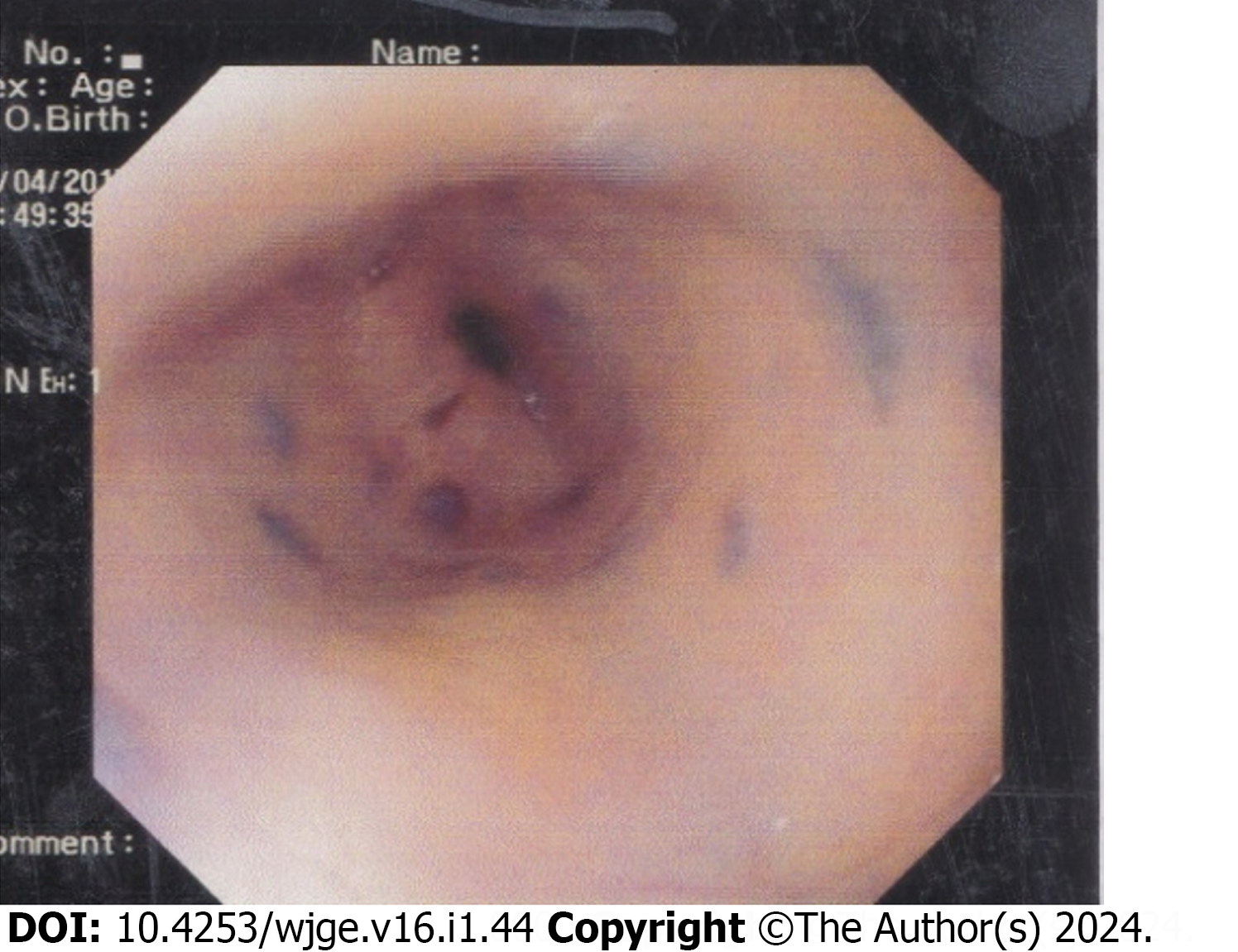

At endoscopy, 65% of patients had esophageal varices and required endotherapy like variceal ligation/sclerotherapy (Figure 1). We observed that 12% of patients had non-variceal bleeding, and 23% of patients had normal UGI endoscopic findings. Among the 12 patients who had non-variceal bleeding, 5 patients had gastric erosion, 1 patient had features of gastroesophageal reflux disease, 1 patient had nonconclusive findings but was ultimately diagnosed with hemophilia, 1 patient had features of blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (Figures 2 and 3), 1 patient had a Mallory-Weiss tear, 2 patients had prolapsed gastropathy (Figure 4), and 1 patient with an eroded posterior duodenal artery from a duodenal ulcer underwent emergency laparotomic ligation of the eroded posterior duodenal artery (Table 2).

| Variable | Value |

| Normal | 23 (23) |

| Esophageal varices | 65 (65) |

| Extrahepatic PHTN | 47 (47) |

| CLD with PHTN | 18 (18) |

| Non-variceal causes | |

| Gastric erosion | 5 (5) |

| GERD | 1 (1) |

| Hemophilia | 1 (1) |

| BRBNS | 1 (1) |

| MWT | 1 (1) |

| PGS | 2 (2) |

| Duodenal artery erosion | 1 (1) |

There were no patients with UGIB that was caused by foreign body ingestion. UGIB was caused in 65% of patients by variceal bleeding from ruptured esophageal varices. Among them, 47 patients were ultimately diagnosed with extrahepatic portal hypertension, and 18 patients were diagnosed with chronic liver disease (CLD). The etiology of CLD included Wilson’s disease (12 patients), post-Kasai procedure for biliary atresia (1 patient), autoimmune hepatitis (1 patient), congenital hepatic fibrosis (1 patient), and cryptogenic (3 patients). The cause was idiopathic in 23 cases.

In the current study, the male to female ratio was 1.6:1, which is similar to another study of UGIB in children[6]. A recent study by Dubey et al[8] showed that UGIB was more common in the 5-10 year age group (71.4%). We also found that the majority of children (42%) were in the 5-10 year group.

Variceal bleeding from portal hypertension was the most common cause (65%) of UGIB in this study. In another study, portal hypertension accounted for 95% of cases[9]. The variceal bleeding rate of our study was very high in comparison to 10.6% in the Western hemisphere (South America and North America)[5,10,11]. These differences may be explained by referral bias (i.e. the majority of non-variceal bleeding cases were managed in non-tertiary healthcare centers, while variceal bleeding cases were referred to our tertiary care center). In addition, geographic variation of disease states resulting in UGIB may play a factor.

Among the variceal bleeding cases, extrahepatic portal hypertension was the major cause in 47% of patients, whereas 18% of patients were diagnosed with CLD with portal hypertension. Extrahepatic portal hypertension was also found to be a common cause (46%) of variceal bleeding in another study from a neighboring country[9,12]. In a study from India, 16.1% of cases of UGIB were caused by CLD with portal hypertension, which is similar to our findings (18%)[8]. Our study showed that Wilson’s disease was the most common cause (12%) of CLD with portal hypertension and may be related to the burden of consanguineous marriage and/or referral bias. We found that 3% of UGIB cases were due to cryptogenic CLD with portal hypertension, which may be explained by the lack of modern laboratory facilities to diagnose metabolic liver diseases other than Wilson’s disease.

During the evaluation of the 100 children with UGIB, we found that 12% of children had non-variceal bleeding. Among them, gastric erosion was found in 5% of cases, which is similar (9%) to another study from India[12]. This may be partially explained by parents using self-medication (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs/traditional medications) during minor trauma, high fever, etc. Other endoscopic diagnosis were blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome, Mallory-Weiss tear, prolapsed gastropathy syndrome, and posterior duodenal artery erosion from duodenal ulcer. In our series, there were 23 idiopathic cases, which is similar to the findings from Mittal et al[12]. Cleveland et al[6] also found normal or doubtful sources on endoscopy in 42% of their cases. Normal UGI endoscopy findings may suggest minor mucosal lesions or extra GI sources (i.e. swallowed blood).

Upper GI endoscopic evaluation of children with UGIB showed ruptured esophageal varices were the most common cause of UGIB in Bangladesh.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is defined as bleeding that occurs proximal to the ligament of Treitz and can sometimes lead to potentially serious and life-threatening clinical situations in children. The etiology of UGIB in children is diverse and causes vary with age, geographical location and associated comorbidity.

There is a paucity of data regarding the etiology, mode of presentation and endoscopic findings of UGIB in children of Bangladesh.

The purpose of the study was to observe endoscopic findings of 100 cases of UGIB that were admitted in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, a tertiary care hospital of Bangladesh.

This retrospective observational study was carried out in the department of Pediatric Gastroenterology of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University of Bangladesh. Data were collected from hospital records after approval from the departmental ethical committee. In total, 100 children who were 16 years of age or younger presented with hematemesis and/or melaena and underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy after stabilization of vitals within 24-48 h. Patients who were older than 16 years of age or presented with bright red per rectal bleeding were excluded. All patients were treated according to the standard departmental protocol. The study was approved by the departmental Ethics Committee. Statistical analysis were performed using frequency, means, standard deviations and proportions.

A total of 100 patients were studied. UGIB was most common in the 5-10 years age group (42%), followed by those older than 10 years (37%). Hematemesis was the most common presenting symptom (75%) followed by both hematemesis and melena (25%). UGIB from ruptured esophageal varices was the most common cause (65%) on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy followed by gastric erosion (5%) and prolapsed gastropathy (2%). We observed that 23% of patients had a normal endoscopy.

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopic evaluation of children with UGIB showed that ruptured esophageal varices were the most common cause of UGIB in Bangladesh. Non-gastrointestinal causes like hemophilia may also present with gastrointestinal bleeding.

Further multicenter studies should be conducted to determine non-gastrointestinal causes of UGIB.

All doctors, staff and patients of the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition of Bangabandhu Shiekh Mujib Medical University.

| 1. | Poddar U. Diagnostic and therapeutic approach to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Paediatr Int Child Health. 2019;39:18-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Russell RCG, Williams NS, Bulstrode CJL. Bailey and love’s short practice of surgery. 23rd ed. London: Arnold; 2000. p. 45–52. |

| 3. | Walker B, Colledge N, Ralston S, Davidson S. Davidson’s principles and practice of medicine. 22nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2014. p. 854. ISBN 978–0–7020–5103–6. |

| 4. | Grimaldi-Bensouda L, Abenhaim L, Michaud L, Mouterde O, Jonville-Béra AP, Giraudeau B, David B, Autret-Leca E. Clinical features and risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children: a case-crossover study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | El Mouzan MI, Abdullah AM, Al-Mofleh IA. Yield of endoscopy in children with hematemesis. Trop Gastroenterol. 2004;25:44-46. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cleveland K, Ahmad N, Bishop P, Nowicki M. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children: an 11-year retrospective endoscopic investigation. World J Pediatr. 2012;8:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chawla S, Seth D, Mahajan P, Kamat D. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46:16-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Dubey SRK Bhadauria N, Shukla M, Mittal P, Arya AK, Singh RP. Clinico-etiological pattern of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children. Int J Contemp Pediatr. 2017;4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Yachha SK, Khanduri A, Sharma BC, Kumar M. Gastrointestinal bleeding in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;11:903-907. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Dehghani SM, Haghighat M, Imanieh MH, Tabebordbar MR. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in children in Southern Iran. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:635-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Akasaka Y, Misaki F, Miyaoka T, Nakajima M, Kawai K. Endoscopy in pediatric patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;23:199-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mittal SK, Kalra KK, Aggarwal V. Diagnostic upper GI endoscopy for hemetemesis in children: experience from a pediatric gastroenterology centre in north India. Indian J Pediatr. 1994;61:651-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author’s Membership in Professional Societies: Bangladesh Gastroenterology Society, A0167.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Bangladesh

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Rodrigues AT, Brazil S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Cai YX