Published online Dec 16, 2023. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v15.i12.745

Peer-review started: September 21, 2023

First decision: October 24, 2023

Revised: October 30, 2023

Accepted: December 1, 2023

Article in press: December 1, 2023

Published online: December 16, 2023

Processing time: 84 Days and 20.8 Hours

Endoscopic balloon dilation is a minimally invasive treatment for colorectal stenosis. Magnetic compression anastomosis can be applied against gastroi

We have reported here the case of a 53-year-old female patient who underwent a descending colostomy due to sigmoid obstruction. Postoperative fistula resto

This case report proposes a novel minimally invasive treatment approach for colorectal stenosis.

Core Tip: Colorectal stenosis is common in clinical practice, for which endoscopic treatment is the preferred choice; however, most patients require multiple balloon dilation or even stent placement. Clinicians should consider the novel approach of endoscopic magnetic compression anastomosis in applicable cases of colorectal stenosis.

- Citation: Zhang MM, Gao Y, Ren XY, Sha HC, Lyu Y, Dong FF, Yan XP. Magnetic compression anastomosis for sigmoid stenosis treatment: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2023; 15(12): 745-750

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v15/i12/745.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v15.i12.745

Colorectal anastomotic stenosis usually occurs after colorectal cancer surgery or even after radiation therapy for abdominal and pelvic tumors. Endoscopic balloon dilation or stent placement is the main clinical approach in such cases. However, some patients with severe stenosis often require multiple endoscopic treatments, albeit show poor outcomes. Re-surgery may incur a very high rate of restenosis and refrain patients from an opportunity to restore the stoma, which may seriously affect their quality of life. The combination of magnetic compression anastomosis with endoscopic technique provides a new minimally invasive treatment modality for rectal stenosis.

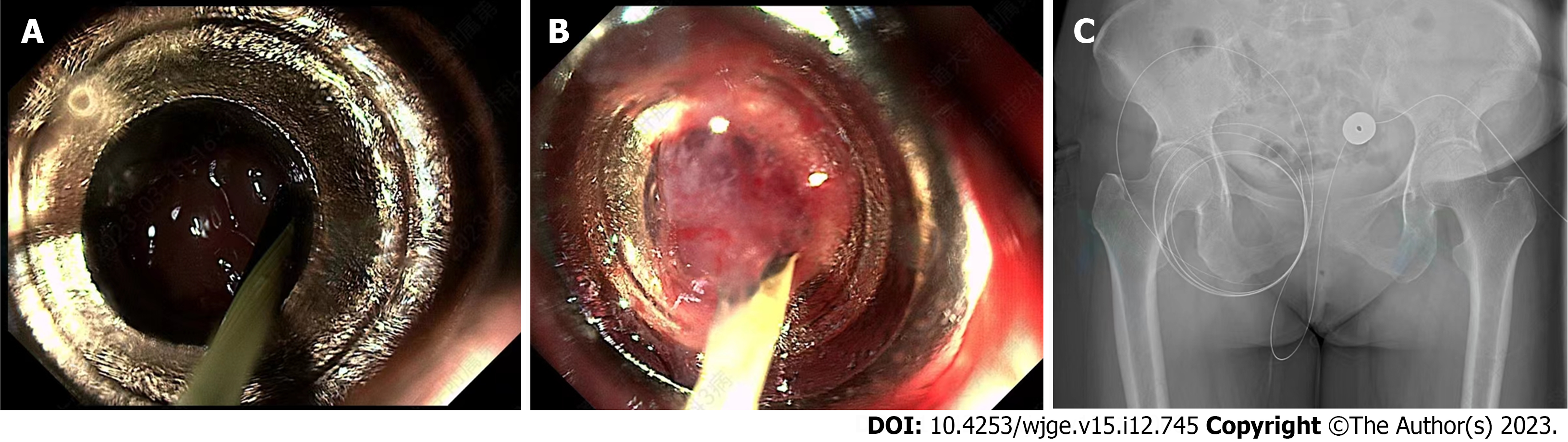

A 53-year-old female patient was admitted to our hospital on July 26, 2022, for sigmoid stenosis. The patient had undergone a descending colostomy in a local hospital for sigmoid obstruction 11 mo ago and had recovered well after surgery. One month ago, she was treated in the same hospital for a reduction colostomy. A colonoscopy revealed that her sigmoid was narrow (Figure 1), hence the reduction operation could not be performed. For further treatment, the patient was admitted to the Magnetic Surgery Clinic of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

At 11 mo ago, the patient underwent a descending colostomy in a local hospital for sigmoid obstruction and a colonoscopy 1 mo before the indication of sigmoid stenosis.

The patient was diagnosed with cervical cancer at a local hospital 9 years ago and has been clinically cured after multiple radiotherapy treatments. She has a history of hypertension for 1 year and diabetes for 2 years. Through oral drug treatment, her blood pressure and blood glucose levels were well-controlled.

The patient did not have any relevant family medical history.

The patient's vital signs were stable, with no obvious abnormalities in the physical examination of both her lungs and heart; her abdomen was flat and soft, with no abdominal tenderness; Shifting dullness in the abdomen was negative, and bowel sounds were normal, and the descending colostomy stoma was visible in the left lower abdomen.

The patient's hematology results were normal.

A small amount of contrast agent could enter the proximal intestinal tube through the stenosis, and the intestinal tube could be fully developed through the catheterization of the colostomy, indicating sigmoid stenosis (Figure 2).

According to the medical history of the patient, imaging examination, and colonoscopy, sigmoid stenosis was clearly diagnosed.

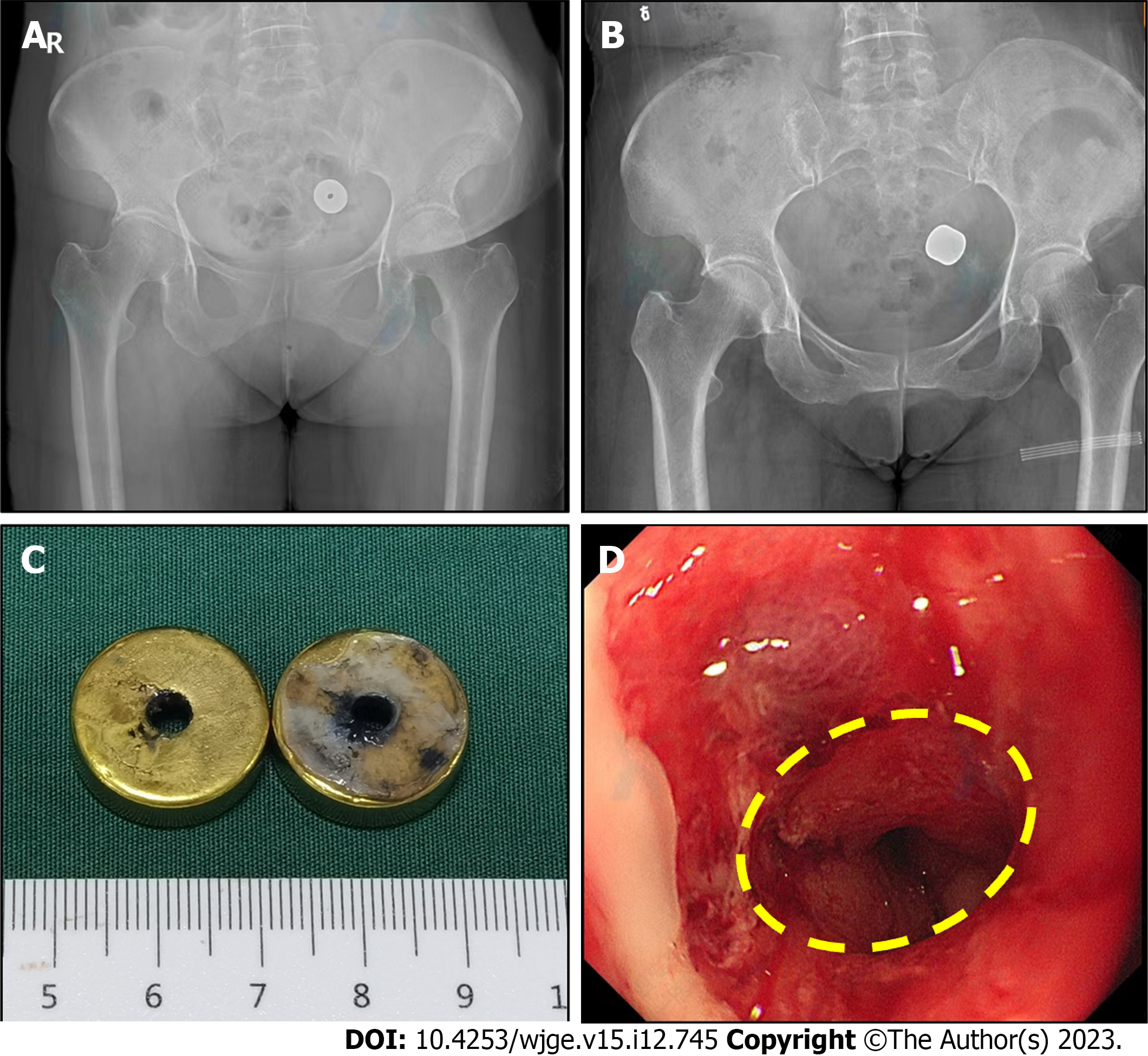

The patient underwent endoscopy-assisted magnetic compression anastomosis of sigmoid stenosis under intravenous anesthesia on July 27, 2022. After the patient was administered intravenous anesthesia, a colonoscopy was conducted in the right lateral position through the descending colostomy. A stenosis could be visible at a distance of 15 centimeters from the colostomy during colonoscopy. A zebra guide wire was next sent through the biopsy hole, and the lead end of the guide wire was passed through the narrow segment of the sigmoid colon into the distal intestinal. The daughter magnet and the parent magnet were inserted through the zebra guide wire at the end of the colostomy and the anal end, respectively, and the push tube was pushed close to the narrow section along the zebra guide wire, as such the parent and daughter magnets were automatically attracted (Figure 3A and B). After the X-ray images confirmed that the magnets were attracted (Figure 3C), the zebra guide wire was removed. After the operation, the patient was returned to the ward safely.

X-ray examination was performed weekly after the operation to monitor the positions of the magnets (Figure 4A and B). On the 15th day of the operation, the parent and daughter magnets were removed via colonoscopy (Figure 4C). The magnetic compression anastomosis was established under colonoscopy (Figure 4D). Finally, the patient underwent colostomy reduction 10 d later.

The 13-mo follow-up of the patient showed a generally good condition with normal bowel movements.

Colorectal stenosis is a common clinical disease, whose clinical treatment is mainly based on endoscopic balloon dilation or stent placement[1], it has the advantages of less trauma and not affected by enterostomy. However, some patients often require multiple endoscopic treatments. Patients who do not respond well to endoscopic therapy may face re-surgery or permanent indwelling. In 1978, Obora et al[2] was the first to report the use of magnets for vascular anastomosis research[2], and after more than 40 years of its development, magnetic compression anastomosis is being applied for digestive tract anastomosis[3,4], vascular anastomosis[5,6], and magnetic compression cystostomy[7]. The combination of magnetic compression anastomosis and endoscopic technique can transform some surgical operations into endoscopic ones, which offers unique advantages for the treatment of gastrointestinal stenosis[8].

This present case presented the following two characteristics: (1) The surgical procedure was simple, mainly because the zebra guide wire could pass through the narrow section of the intestinal tube and the length of the narrow section was small, because of which the magnetic force of conventional magnets met the requirements; (2) The parent and daughter magnets remained discharged for 2 wk. The shedding time of magnets during digestive tract magnetic compression anastomosis is closely related to the anastomosis site, magnetic force, inflammatory scar formation of the digestive tract, and other related factors. Owing to the limited clinical reports on such cases, it remains impossible to determine the reasonable time range of magnets excreted during the digestive tract magnetic compression anastomosis. In our previous large animal experiments, we found that gastrointestinal magnetic compression anastomosis could be established in 10–14 d after the surgery. Therefore, in the present case, we removed the magnets under the endoscope 15 d after the surgery, and the results indicated that the anastomosis was well-formed by this time; and (3) Based on the patient's history, we believe that the cause of the patient's sigmoid stenosis may be related to pelvic radiation therapy. Radiation enteritis is usually treated with medication or endoscopy, but this patient developed severe sigmoid stenosis and caused intestinal obstruction, and did not respond to medication or endoscopy. Presently, only a few cases have been reported in the literature using magnetic compression anastomosis to treat colorectal stenosis, and the relevant clinical application experience is limited. The successful implementation of this case thus enriches the clinical application experience of magnetic surgery and can provide valuable learning and reference significance for future applications.

This case report proposes a new approach for clinicians to treat colorectal stenosis. A combination of magnetic compression anastomosis with endoscopic technique can be potentially applied for the treatment of colorectal stenosis, considering the advantages of simple operation, non-trauma, and exact effect achieved through this procedure.

| 1. | Hirai F. Current status of endoscopic balloon dilation for Crohn's disease. Intest Res. 2017;15:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Obora Y, Tamaki N, Matsumoto S. Nonsuture microvascular anastomosis using magnet rings: preliminary report. Surg Neurol. 1978;9:117-120. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pichakron KO, Jelin EB, Hirose S, Curran PF, Jamshidi R, Stephenson JT, Fechter R, Strange M, Harrison MR. Magnamosis II: Magnetic compression anastomosis for minimally invasive gastrojejunostomy and jejunojejunostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:42-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gonzales KD, Douglas G, Pichakron KO, Kwiat DA, Gallardo SG, Encinas JL, Hirose S, Harrison MR. Magnamosis III: delivery of a magnetic compression anastomosis device using minimally invasive endoscopic techniques. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1291-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zhang M, Ma J, An Y, Lyu Y, Yan X. Construction of an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt using the magnetic compression technique: preliminary experiments in a canine model. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2022;11:611-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Filsoufi F, Farivar RS, Aklog L, Anderson CA, Chen RH, Lichtenstein S, Zhang J, Adams DH. Automated distal coronary bypass with a novel magnetic coupler (MVP system). J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uygun I, Okur MH, Cimen H, Keles A, Yalcin O, Ozturk H, Otcu S. Magnetic compression ostomy as new cystostomy technique in the rat: magnacystostomy. Urology. 2012;79:738-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yan XP, Shang P, Shi AH, Liu WY, Liu YX, Lv Y. [Exploration and establishment of magnetic surgery]. Kexue Tongbao. 2019;64:815-826. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nakamura K, Japan; Yarmahmoodi F, Iran S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX