Published online Sep 16, 2020. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v12.i9.297

Peer-review started: May 8, 2020

First decision: May 26, 2020

Revised: June 4, 2020

Accepted: August 15, 2020

Article in press: August 15, 2020

Published online: September 16, 2020

Processing time: 120 Days and 12.3 Hours

Acute gastric remnant bleeding is a rare complication of bariatric surgery. Furthermore, acute bleeding from the gastric remnant resulting in gastric remnant outlet obstruction has not been described previously. Endoscopic management of gastric remnant bleed has been challenging due to difficulty accessing the excluded stomach. Traditionally, this necessitates surgical intervention. Recently, however, the adoption of endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric intervention provides an alternative approach to management.

A 65-year-old male with a prior gastric bypass presented with the sudden onset of progressive abdominal distension, nausea, and melena of two days duration. His imaging illustrated a massively distended stomach. A nasogastric tube did not result in drainage of fluid or decompression of his abdomen. His endoscopy revealed a normal-appearing gastro-jejunal anastomosis and confirmed the distended "fluid"-filled gastric remnant. An endoscopic ultrasound-directed gastrogastrostomy was created to decompress the gastric remnant. Two liters of blood was suctioned before a large adherent clot was visualized in the gastric antrum. The patient underwent emergent angiography with embolization of the gastroduodenal artery. He was discharged with a stable hemoglobin level and resolution of symptoms. Healing superficial gastric ulcers were visualized on a follow-up endoscopy. Gastric biopsies were consistent with Helicobacter pylori infection for which the patient was treated, and successful eradication was achieved.

This patient benefited from a timely diagnosis and effective therapy of an acute gastric remnant obstruction from a bleeding ulcer with endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric intervention.

Core Tip: The gastric remnant can be safely and effectively accessed by endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric intervention by the formation of a gastrogastrostomy using a lumen apposing metal stent to treat several conditions, including but not limited to bleeding gastric ulcers and gastric outlet obstruction among patients who have previously undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. This method is an effective, safe, and less invasive alternative to surgery.

- Citation: Zarrin A, Sorathia S, Choksi V, Kaplan SR, Kasmin F. Endoscopic approach to gastric remnant outlet obstruction after gastric bypass: A case report. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2020; 12(9): 297-303

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v12/i9/297.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v12.i9.297

Complications following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) can be acute or chronic and can be potentially life-threatening if not immediately recognized and treated. Complications of the pancreatobiliary limb (PBL) and the excluded stomach after RYGB have been reported. However, acute gastric remnant bleeding is an infrequent complication of bariatric surgery. Endoscopic management with either push or balloon enteroscopy is challenging due to technical difficulties in accessing the excluded stomach. In most cases, surgical intervention is necessary and is the standard approach[1,2].

We present a patient who had a timely diagnosis and successful treatment with endoscopic decompression using a lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS). This approach is more recently described under the spectrum of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) directed transgastric intervention (EDGI). EDGI defines any EUS-directed procedure requiring transgastric intervention to adjacent luminal structures, including the gastric remnant among RYGB patients[3]. Several studies have shown EDGI to be more effective than balloon enteroscopy, and equally as effective as a surgical intervention with fewer complications.

A 65-year-old male presented with the sudden onset of progressive abdominal distension.

The patient’s symptoms started two days prior and included associated nausea, dry-heaves, lightheadedness, and melena.

His only medical history is a remote RYGB eight years prior for weight loss.

The patient denied further medical history. He also denied a history of tobacco, alcohol, and NSAID use. His father died of myocardial infarction at age 70 and his mother was diabetic. He denied a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy.

On presentation, he was afebrile and hemodynamically stable. However, he appeared pale with conjunctival pallor. The abdomen was distended but non-tender with normal bowel sounds. The rectal exam exhibited melena.

Complete blood count and complete metabolic panel were notable for a hemoglobin of 12 g/dL and hematocrit of 35.8%, which were near his baseline. His blood urea nitrogen was 23 mg/dL and his creatinine was 0.8 mg/dL. The remainder of these laboratory examinations, including liver enzymes and coagulation studies, were within normal limits.

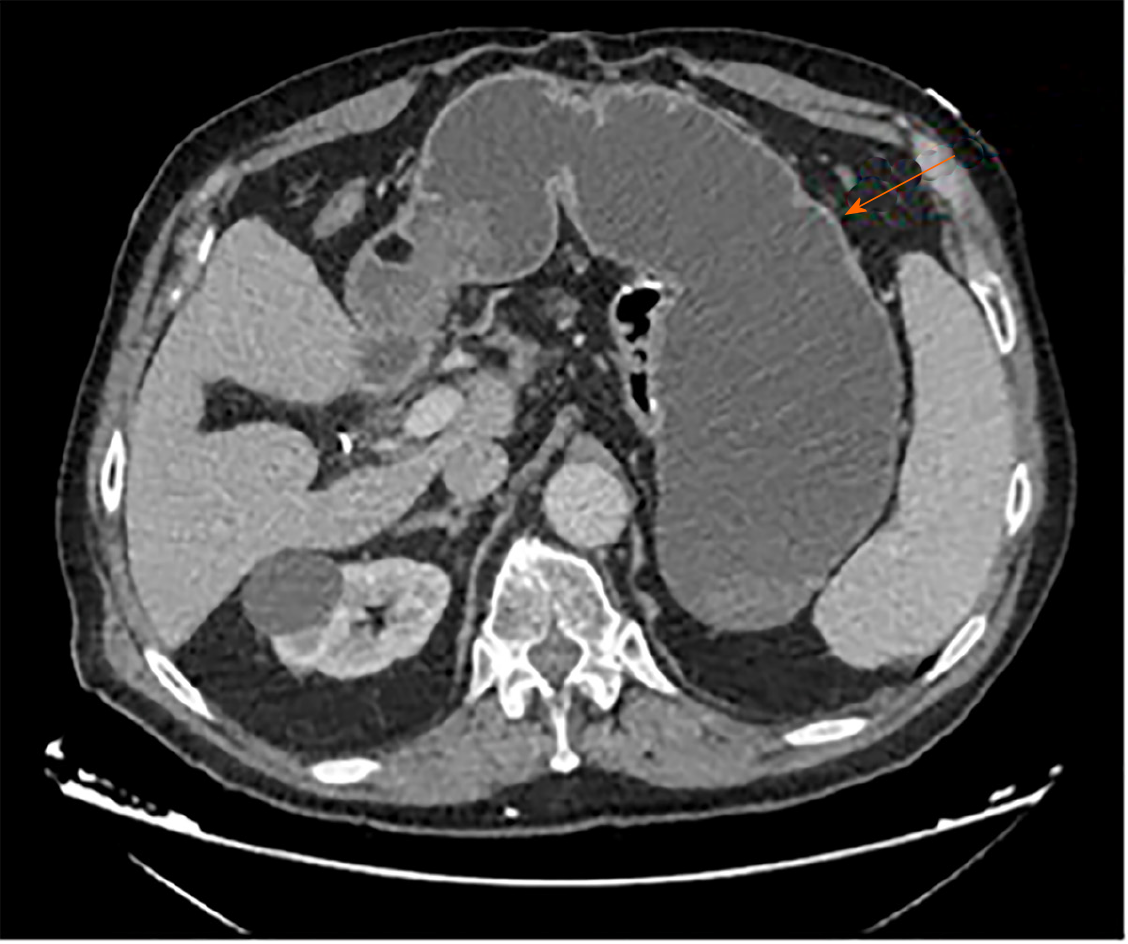

Chest X-ray was normal. A subsequent computerized tomography scan with intravenous contrast illustrated a massively distended stomach, which was "fluid"-filled (Figure 1).

A nasogastric tube was inserted, which did not result in any immediate drainage of fluid or decompression of his abdomen.

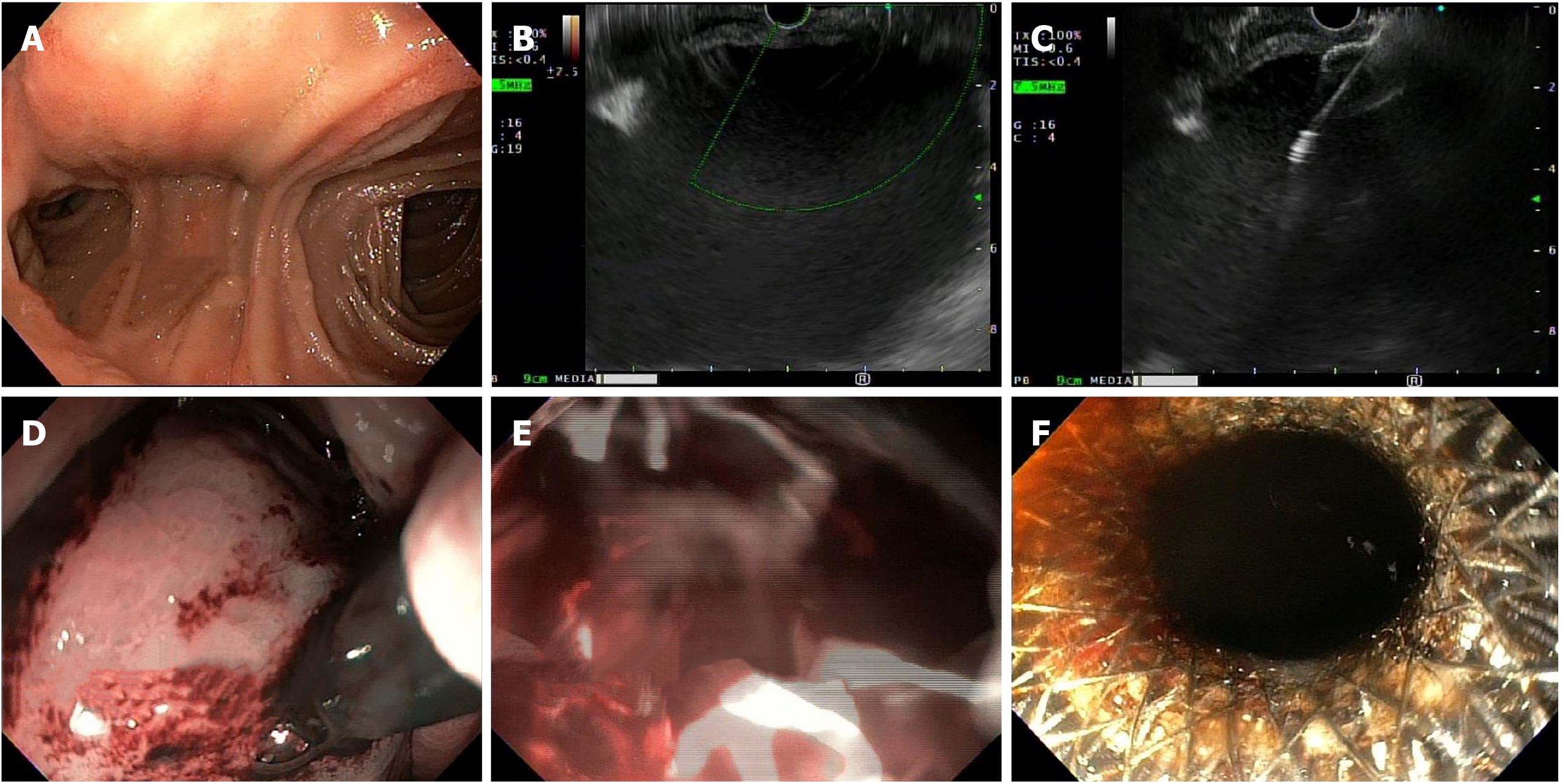

He immediately underwent an emergent upper endoscopy and EUS for decompression of the gastric remnant. The endoscopy revealed a normal-appearing gastro-jejunal anastomosis without marginal ulceration or evidence of active or recent bleeding in either limb. EUS confirmed the distended "fluid"-filled gastric remnant. We then proceeded to decompress the gastric remnant by creating a gastro-gastrostomy using a Hot AXIOSTM LAMS delivery system. Fine needle aspiration with a 19-gauge needle into the "fluid"-filled gastric remnant revealed maroon aspirate. A safe window for stent placement was found using doppler guidance. A 15 mm × 10 mm AXIOSTM stent was deployed, first by rapidly puncturing the fluid cavity under doppler guidance with the AXIOSTM tip electrified at 90 Watts, then by the ultrasound-controlled deployment of the inner phalange of the stent, and then finally by the endoscopy-controlled deployment of the outer phalange in the lumen of the gastric pouch. Upon deployment, maroon-colored blood immediately started draining. After extensive suctioning, the gastric remnant was decompressed (Figure 2).

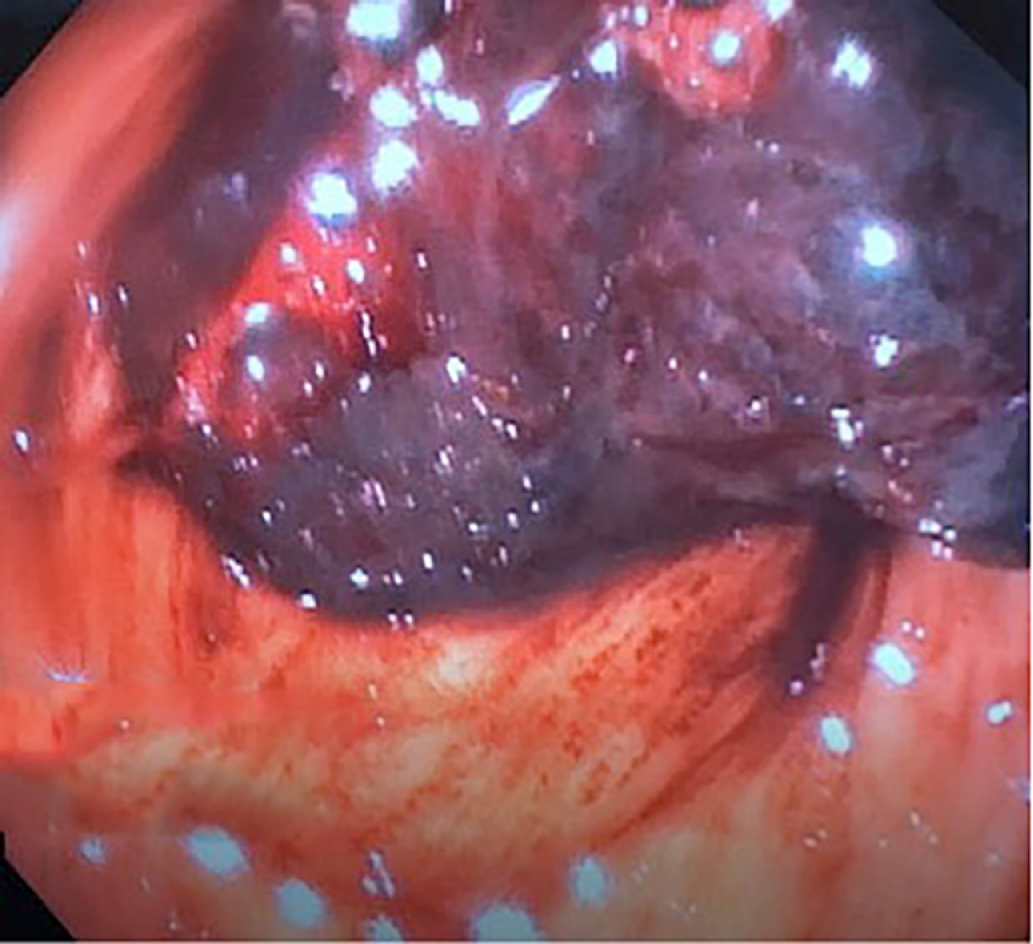

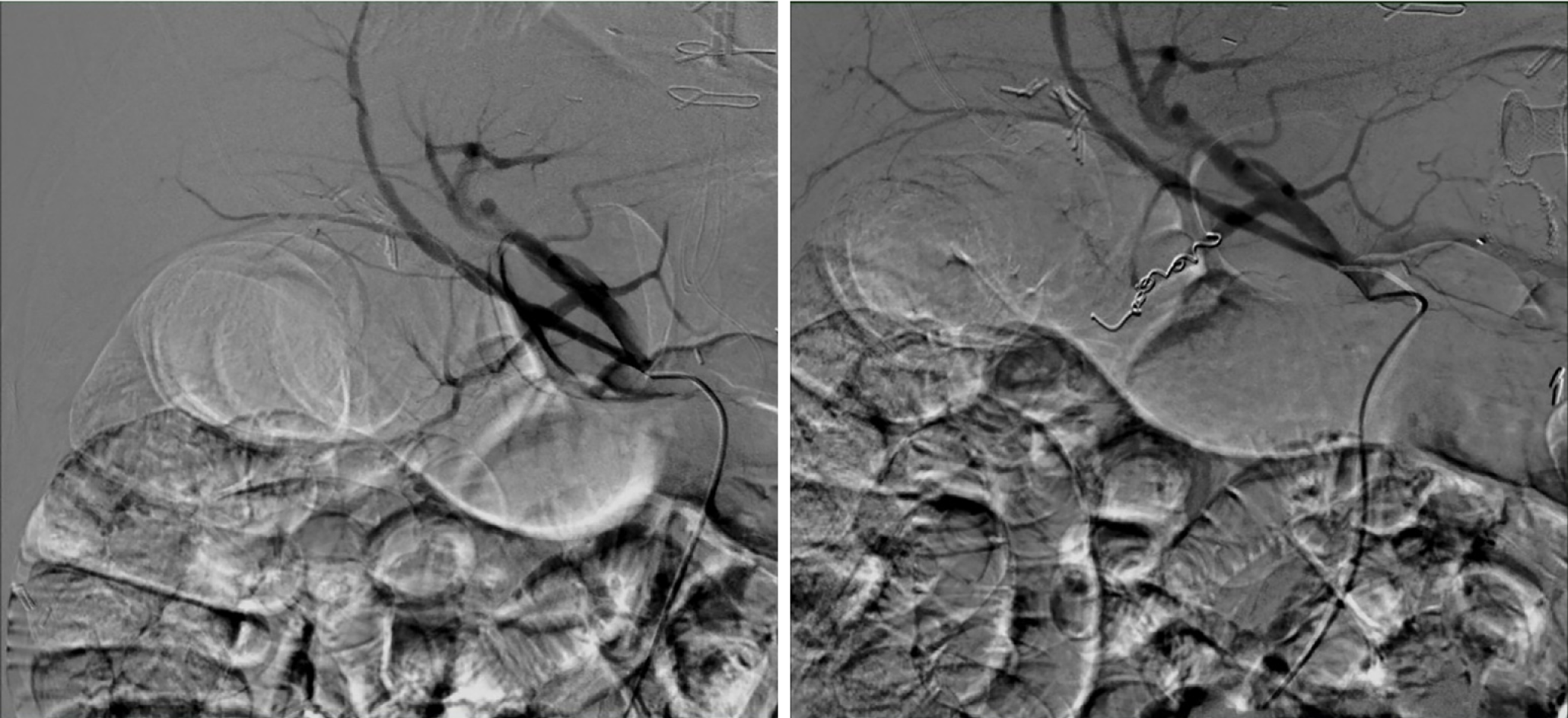

Next, balloon dilatation of the stent allowed a gastroscope to access the gastric remnant. Approximately two liters of blood was suctioned before a large adherent clot was visualized in the gastric antrum. Fresh blood was observed oozing around the clot (Figure 3). Endoscopic therapy was not pursued due to the sheer size of the clot and concern of stent dislodgement. The patient was sent for emergent angiography with embolization of the gastroduodenal artery (Figure 4). He remained hospitalized for two additional days. He was discharged with a stable hemoglobin level and resolution of abdominal distension and bleeding. After a three-week interval, a repeat endoscopy for evaluation of the gastric remnant through the gastrogastric fistula was performed. Healing superficial gastric ulcers were visualized (Figure 5). The LAMS was left in place with plans for removal at an interval date. Gastric biopsies were consistent with Helicobacter pylori infection for which the patient was treated, and successful eradication was achieved.

Helicobacter Pylori infection-induced gastric remnant ulcer bleeding causing outlet obstruction.

Endoscopic ultrasound-directed transgastric intervention, gastroduodenal artery embolization, and triple therapy including Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, and Pantoprazole dosed twice daily for a duration of 14 d. This was the treatment of choice given low rates of Clarithromycin resistance in our area and lack of patient risk factors for Clarithromycin resistance.

The patient recovered well without complications or weight gain. He completed the course of triple therapy and has not had a recurrence of symptoms. Successful eradication was achieved. He is scheduled for retrieval of his lumen apposing metal stent.

Marginal ulcers comprise the vast majority of gastrointestinal bleeding complications in patients who have undergone a RYGB, with an estimated incidence of 0.6%-16%[4]. Marginal ulcers are easily diagnosed and treated with conventional upper endoscopy. However, ulceration of the gastric remnant or duodenum is rare, with approximately 25 reported cases in the literature[5-10]. Risk factors for developing such ulcers include hyperacidity of the gastric remnant without the buffering effect of ingested food, bile acid reflux, NSAIDs use, and Helicobacter pylori infection[9]. Most instances of obstruction of the gastric remnant were due to malignancy. Pyloric stenosis was reported as a benign etiology in only one case study[11]. We were unable to uncover any instances of outlet obstruction of the gastric remnant caused by bleeding ulcers.

Historically, ulceration of the gastric remnant and duodenum has been treated by laparotomy and endoscopy through either a surgical gastrostomy or by enteroscopy. Hakim et al[9] describe two cases of afferent limb bleeding with successful exploration and treatment by push enteroscopy or single-balloon enteroscopy[9]. However, this method is not always successful due to difficulty intubating the excluded segment. The low success rate is due to difficulty reaching the duodenum and gastric remnant[1,2].

Our case supports the use of an alternative and less invasive approach to gastric outlet obstruction of the gastric remnant through EUS-directed creation of gastrogastrostomy with a LAMS. This method is diagnostic, giving the operator the ability to visualize the pathological process by an antegrade approach. It is also therapeutic, forming a conduit by which built up secretions and blood can drain into the patent roux limb, as well as allowing for endoscopic hemostasis to be attempted. The necessity to treat pancreaticobiliary disease with ERCP following a RYGB has resulted in the advent of EUS-directed transgastric ERCP (EDGE). More recently, this method has been grouped under the umbrella term "EDGI", a phrase coined by Krafft et al[3] to highlight the increasing use of this method for accessing the PBL for other diagnostic and therapeutic interventions in addition to ERCP[3].

Studies on EDGE have shown EUS-directed access of the gastric remnant to be clinically safe and effective. Xu et al[12] describe a case of bile leak that was successfully treated with ERCP performed through a gastrogastrostomy formed by EUS-directed LAMS placement[12]. The high success rate of accessing the PBL by EUS guidance is highlighted by Kedia et al[13]. In their study, technical success, which was defined as successful deployment of LAMS to form either gastrogastrostomy or jejunogastrostomy, was 100%. Clinical success, which was defined as successful endoscopy through the LAMS, was 90%. Complications included LAMS migration at the index procedure in three patients and jejunal perforation with the insertion of the duodenoscope through the LAMS in one patient. Importantly, none of these patients suffered from clinical sequelae or necessitated surgical intervention[13,14].

An international, multicenter study of patients who demonstrated the safety and efficacy of EDGI for either benign or malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Not only was the success rate comparable to the surgical approach, but it also was successful as salvage therapy for patients who failed surgery. Adverse events occurred in 11.5%. In comparison, the complication rate of surgical gastrojejunostomy has been reported to be as high as 40%[15]. Follow-up data after EDGE for these patients revealed no symptom recurrence after a mean follow-up of 7.9 wk in the clinically successful cases[16]. Though none of these patients presented with bleeding ulcers causing outlet obstruction of the gastric remnant, as in our case, these studies provide evidence for the safety and efficacy of EUS-directed gastrogastrostomy formation with LAMS.

Krafft et al[3] provide direct evidence for clinical and technical effectiveness, as well as safety for EDGI in cases with indications other than ERCP. Their multicenter, retrospective analysis included patients with RYGB who underwent EDGI for indications including gastroduodenal mass, duodenal ulcer perforation, biopsy of pancreatic mass, drainage of pancreatic fluid collections, and common bile duct dilation. Technical success, defined as successful transmural fistula creation using LAMS, and clinical success, defined as the attainment of diagnosis and partial or complete symptom relief, each showed rates of 100% in this small study[3].

Based on our literature review, this is the first described case of an outlet obstruction of the gastric remnant caused by a bleeding ulcer. This case was successfully managed by the creation of a gastrogastrostomy using a lumen-apposing metal stent. Our case adds to the literature evidence for safe and efficacious access to the gastric remnant by EDGI. It sets a precedent for the use of this technique in treating similar clinical scenarios. This method is an effective, safe, and less invasive alternative to surgery.

| 1. | Tagaya N, Kasama K, Inamine S, Zaha O, Kanke K, Fujii Y, Kanehira E, Hiraishi H, Kubota K. Evaluation of the excluded stomach by double-balloon endoscopy after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1165-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sakai P, Kuga R, Safatle-Ribeiro AV, Faintuch J, Gama-Rodrigues JJ, Ishida RK, Furuya CK, Yamamoto H, Ishioka S. Is it feasible to reach the bypassed stomach after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity? The use of the double-balloon enteroscope. Endoscopy. 2005;37:566-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krafft MR, Hsueh W, James TW, Runge TM, Baron TH, Khashab MA, Irani SS, Nasr JY. The EDGI new take on EDGE: EUS-directed transgastric intervention (EDGI), other than ERCP, for Roux-en-Y gastric bypass anatomy: a multicenter study. Endosc Int Open. 2019;7:E1231-E1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Coblijn UK, Lagarde SM, Tuynman JB, van Meyel JJ, van Wagensveld BA. Delayed massive bleeding two years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. JSLS. 2013;17:476-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Iskandar ME, Chory FM, Goodman ER, Surick BG. Diagnosis and Management of Perforated Duodenal Ulcers following Roux-En-Y Gastric Bypass: A Report of Two Cases and a Review of the Literature. Case Rep Surg. 2015;2015:353468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ivanecz A, Sremec M, Ceranić D, PotrÄ S, Skok P. Life threatening bleeding from duodenal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: Case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:625-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ovaere S, Tse WH, Schipper EE, Spanjersberg WR. Perforation of the gastric remnant in a patient post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Macgregor AM, Pickens NE, Thoburn EK. Perforated peptic ulcer following gastric bypass for obesity. Am Surg. 1999;65:222-225. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hakim S, Reddy SRR, Batke M, Polidori G, Cappell MS. Two case reports of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding from duodenal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: Endoscopic diagnosis and therapy by single balloon or push enteroscopy after missed diagnosis by standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;9:521-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pan A, Sahni S, Khan R, Boulay B. "A Rare Cause of Bleeding After Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: 2020.". Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:S1151-S1152. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Painter TJ, Teixeira AF, Jawad MA. Pyloric stenosis after a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a case report. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11:e9-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu MM, Carames C, Novikov A, Saumoy M, Afaneh C, Kahaleh M, Sharaiha RZ. One-step endoscopic ultrasound-directed gastro-gastrostomy ERCP for treatment of bile leak. Endoscopy. 2017;49:715-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kedia P, Tarnasky PR, Nieto J, Steele SL, Siddiqui A, Xu MM, Tyberg A, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. EUS-directed Transgastric ERCP (EDGE) Versus Laparoscopy-assisted ERCP (LA-ERCP) for Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass (RYGB) Anatomy: A Multicenter Early Comparative Experience of Clinical Outcomes. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:304-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tyberg A, Nieto J, Salgado S, Weaver K, Kedia P, Sharaiha RZ, Gaidhane M, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS)-Directed Transgastric Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography or EUS: Mid-Term Analysis of an Emerging Procedure. Clin Endosc. 2017;50:185-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Medina-Franco H, Abarca-Pérez L, España-Gómez N, Salgado-Nesme N, Ortiz-López LJ, García-Alvarez MN. Morbidity-associated factors after gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Am Surg. 2007;73:871-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tyberg A, Perez-Miranda M, Sanchez-Ocaña R, Peñas I, de la Serna C, Shah J, Binmoeller K, Gaidhane M, Grimm I, Baron T, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy with a lumen-apposing metal stent: a multicenter, international experience. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E276-E281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American College of Physicians, No. 03425464.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Goenka MK S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li JH