Published online Sep 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.200

Peer-review started: February 20, 2018

First decision: March 9, 2018

Revised: March 12, 2018

Accepted: April 2, 2018

Article in press: April 2, 2018

Published online: September 16, 2018

Processing time: 208 Days and 13.2 Hours

To evaluate rates and predictors of hospital readmission and care fragmentation in patients hospitalized with gastroparesis.

We identified all adult hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of gastroparesis in the 2010-2014 National Readmissions Database, which captures statewide readmissions. We excluded patients who died during the hospitalization, and calculated 30 and 90-d unplanned readmission and care fragmentation rates. Readmission to a non-index hospital (i.e., different from the hospital of the index admission) was considered as care fragmentation. A multivariate Cox regression model was used to analyze predictors of 30-d readmissions. Logistic regression was used to determine hospital and patient factors independently associated with 30-d care fragmentation. Patients readmitted within 30 d were followed for 60 d post discharge from the first readmission. Mortality during the first readmission, hospitalization cost, length of stay, and rates of 60-d readmission were compared between those with and without care fragmentation.

There were 30064 admissions with a primary diagnosis of gastroparesis. The rates of 30 and 90-d readmissions were 26.8% and 45.6%, respectively. Younger age, male patient, diabetes, parenteral nutrition, ≥ 4 Elixhauser comorbidities, longer hospital stay (> 5 d), large and metropolitan hospital, and Medicaid insurance were associated with increased hazards of 30-d readmissions. Gastric surgery, routine discharge and private insurance were associated with lower 30-d readmissions. The rates of 30 and 90-d care fragmentation were 28.1% and 33.8%, respectively. Younger age, longer hospital stay (> 5 d), self-pay or Medicaid insurance were associated with increased risk of 30-d care fragmentation. Diabetes, enteral tube placement, parenteral nutrition, large metropolitan hospital, and routine discharge were associated with decreased risk of 30-d fragmentation. Patients who were readmitted to a non-index hospital had longer length of stay (6.5 vs 5.8 d, P = 0.03), and higher mean hospitalization cost ($15645 vs $12311, P < 0.0001), compared to those readmitted to the index hospital. There were no differences in mortality (1.0% vs 1.3%, P = 0.84), and 60-d readmission rate (55.3% vs 54.6%, P = 0.99) between the two groups.

Several factors are associated with the high 30-d readmission and care fragmentation in gastroparesis. Knowledge of these predictors can play a role in implementing effective preventive interventions to high-risk patients.

Core tip: Gastroparesis is associated with high 30-d readmission, and 1 in 4 readmissions occur at a hospital different from the index hospitalization. Measuring same-hospital readmission rates without accounting for non-index hospitalization underestimates readmission rates by 20%. Several factors are associated with 30-d readmission and care fragmentation, and can play a role in implementing effective preventive interventions to high-risk patients. Care fragmentation is associated with increased cost of readmissions and longer hospital stays. Optimizing post discharge care coordination and data sharing between hospitals could decrease care fragmentation and cost of care.

- Citation: Qayed E, Muftah M. Frequency of hospital readmission and care fragmentation in gastroparesis: A nationwide analysis. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(9): 200-209

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i9/200.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i9.200

Gastroparesis is a chronic illness that leads to upper gastrointestinal symptoms of nausea, vomiting, early satiety, and abdominal pain. In the United States, epidemiologic data estimates the incidence of gastroparesis at 2.4 per 100000 person-years and the prevalence at 9.6 per 100000 person-years[1]. Hospital admissions related to gastroparesis have increased over the past two decades. In one study of the nationwide inpatient sample database, annual hospital admissions for gastroparesis increased from 3978 in 1997 to 16460 in 2013[2]. The same study found an increase in hospital charges for gastroparesis admissions from $13350 to $34585 over the same period. Gastroparesis has become of increasing relevance due to its association with poorer quality of life, significant psychological distress, anxiety and depression[3-6].

Given the increasing burden of gastroparesis on patients’ quality of life and on healthcare costs, it is important to identify factors related to hospital readmissions. Knowledge of these predictors can play a role in implementing preventive interventions in high-risk patients. However, few studies addressed this topic. Uppalapati et al[7] found that poor glycemic control, infection, and non-adherence with medical therapy correlated with increased hospital admission rates in gastroparesis. Bielefeldt et al[8] found that more than half of emergency department visits for gastroparesis resulted in admission. Age, cardiovascular, renal, and infectious comorbidities were found to correlate with higher admission rates[8]. None of these studies estimated the readmission rates and risk factors for readmission in gastroparesis.

Due to the chronicity of symptoms of gastroparesis, post discharge care coordination could play an important role in preventing hospital readmission. One negative consequence of lack of care coordination is care fragmentation. This occurs when the patient is discharged from one hospital (index hospital) and is readmitted to a different (non-index) hospital. Studies of care fragmentation in various medical and surgical conditions show that this phenomenon is common and correlates with increased adverse outcomes, hospitalization, and healthcare costs[9-13]. In addition, readmissions to different hospitals leads to underestimation of readmission if the first hospital conducts a readmission analysis that is limited to its institutional database[13].

Given the increasing number of hospitalizations and rising healthcare costs in gastroparesis, we performed this analysis using a nationwide database to study several aspects of hospitalization in gastroparesis. First, we evaluate the rates and predictors of hospital readmission in gastroparesis. Second, we assess the frequency and predictors of care fragmentation using statewide data, and its effect on underestimation of hospital readmission. Lastly, we evaluate the effect of care fragmentation on several outcomes including in-hospital mortality, length of stay, costs, and 60-d readmissions.

We used the National readmission database (NRD) from 2010 to 2014 as the study data source. The NRD is developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). It is a database of all-payer hospitalizations drawn from a sample of 22 state inpatient databases, and accounts for 49.3% of all hospitalizations in the United States[14]. Each hospitalization contains several patient and hospital related variables. The database and description of data elements are publicly available through the HCUP website[15]. Using special patient linkage numbers, the NRD allows tracking of patients who are admitted to any hospital within a state, but not across state lines. The database cannot follow patients across different calendar years, and therefore each year of the database is analyzed separately. The Institutional Review Board determined that the study was exempt from review because the database does not contain protected health information and it cannot be linked to any specific subject.

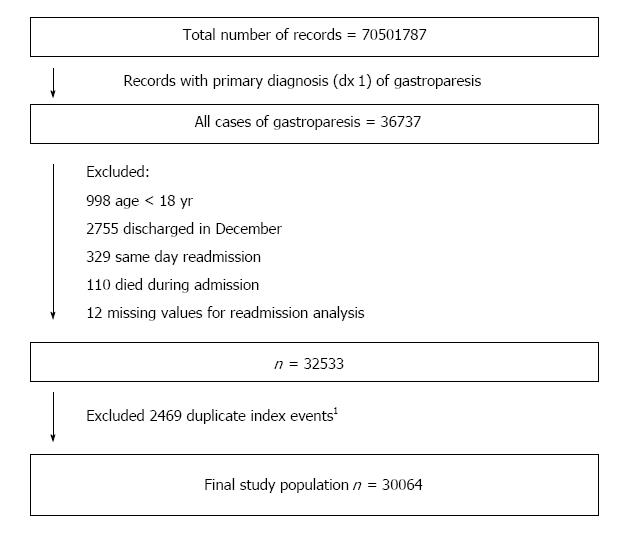

We used the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) to identify all adult (age ≥ 18 years) hospitalizations with the primary discharge diagnosis of gastroparesis (code 536.3). For the purpose of 30-d readmissions, we excluded patients who were discharged in the month of December of each year, in order to have a full 30-d post discharge follow up period to capture readmissions. For the purpose of 90-d readmissions analysis, we excluded records of patients discharged in the month of October, November, and December. We also excluded records of those who died during admission, and records that represent same-day stay pairs of records (patient discharged and readmitted the same day). To avoid duplication, we excluded records that fit the criteria for an index admission, but were also identified as readmissions within 30 d of a previous index admission. We included these records in the readmission analysis. We used predefined tracking variables included in the NRD to identify all-cause unplanned readmissions within a 30 and 90-d period post discharge. As per the recommendations of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, we excluded planned (elective) readmissions[16].

Patient socio-demographic variables included age, sex, and median household income for patient’s ZIP Code. Other variables included primary payer information, length of stay, and discharge disposition. Hospital-related variables included hospital control/ownership status, bed size, and metropolitan status. To control for the risk of readmission, we used the Elixhauser readmission index, which is a validated comorbidity measure derived from 29 comorbidity variables (Table 1). Hospital charges were converted to costs using charge-to-cost ratios provided by the HCUP. We used the consumer price index to inflate costs to 2017 dollars as outlined by the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics[17]. Procedures were identified using ICD-9-CM for procedure codes in any of the procedure fields of the admission record as follows: Gastrostomy 43.11-43.19; jejunostomy 46.32, 46.39; pyloroplasty 44.21, 44.22; pyloromyotomy 43.3; partial gastrectomy 43.5-43.8; total gastrectomy 43.9; parenteral nutrition 99.15.

| Comorbidity variables |

| Paralysis |

| Other neurological disordersl |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Diabetes without chronic complications |

| Diabetes with chronic complications |

| Hypothyroidism |

| Renal failure |

| Liver disease |

| Chronic peptic ulcer disease |

| Human Immunodeficiency Virus or Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| Lymphoma |

| Metastatic cancer |

| Solid tumor without metastasis |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases |

| Coagulation deficiency |

| Obesity |

| Weight loss |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders |

| Blood loss anemia |

| Deficiency anemias |

| Alcohol abuse |

| Drug abuse |

| Psychosis |

| Depression |

| Congestive heart failure |

| Valvular disease |

| Pulmonary circulation disorder |

| Peripheral vascular disorder |

| Hypertension |

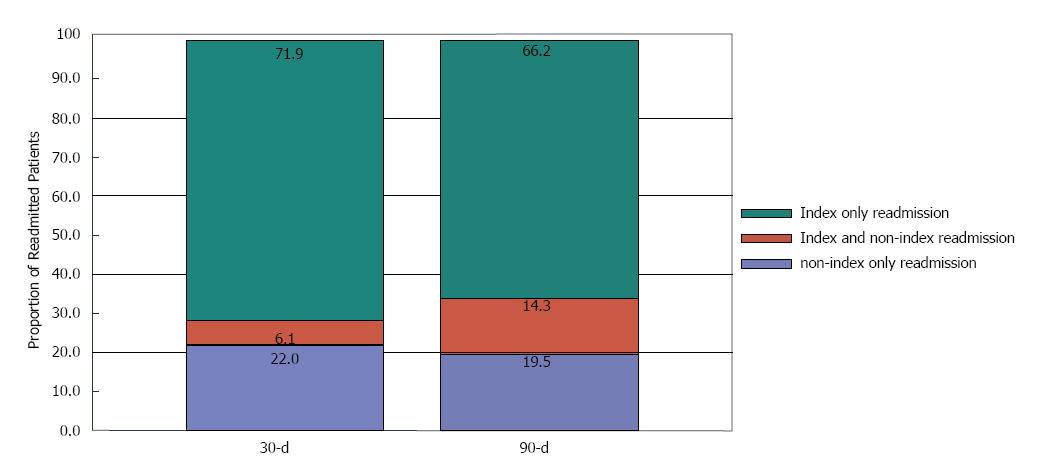

We measured the rates of all-cause 30 and 90-d readmissions and care fragmentation. Index-hospital readmissions were identified as readmissions in which the same hospital identification (ID) code is identified on both the initial hospitalization and the readmission record. Non-index readmissions were identified as readmissions in which a different hospital ID is identified on the readmission record. According to this readmission status, patients were classified into one of three groups: (1) patients with only an index hospital readmission within the 30 or 90-d post discharge period; (2) patients with both index and non-index readmission(s) during follow up; and (3) patients with only a non-index readmission. Patients who were transferred from a non-index hospital to an index hospital were considered as if they were admitted to an index-hospital. This was done because the NRD combines hospital transfers into one discharge record. Care fragmentation was calculated by dividing the number of patients who had any non-index hospitalization (groups 2 and 3) by the total number of readmissions. To calculate the underestimation of hospital readmissions if only index hospital readmissions were used, we divided the number of patients with only a non-index readmission by the total number of readmissions.

Categorical variables were described as number (percentage); while continuous variables were reported as as mean (standard deviation). Baseline characteristics of patients who did and did not experience a readmission were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the t test for continuous variables. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to analyze predictors of 30-d readmissions. Multivariable logistic regression was used to analyze predictors of 30-d care fragmentation. Covariates with P < 0.2 on univariate analysis were entered into the model and retained if the P is < 0.05. Results of multivariable analysis were expressed using adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) or adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95%CI. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to evaluate the relationship between non-index readmission (care fragmentation) and readmission length of stay. Patients with a hospital stay > 30 d were censored at 30 d. We used a multivariable linear regression model to evaluate the relationship between non-index readmission and total costs of hospital stay during the first readmission. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the effect of care fragmentation on in-hospital mortality during the first readmission. A 2-tailed P of 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

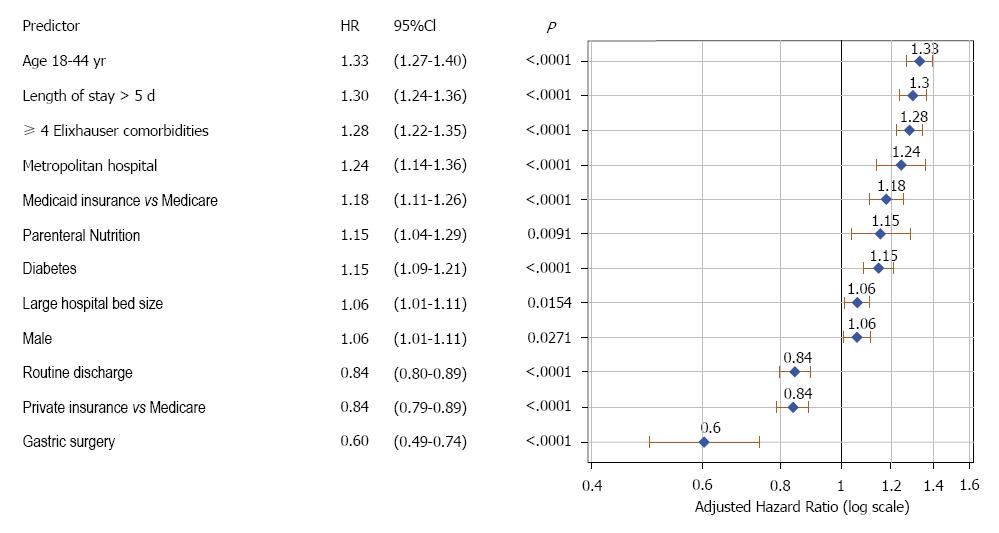

During the study period, there were 30064 total admissions for gastroparesis that fit the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The mean age was 49.6 years (SD = 17), and 74.2% were females. Of these, 8057 (26.8%) had at least one readmission within 30-d. Table 2 shows the characteristics of patients, stratified by readmission status. Patients who experienced a 30-d readmission were more likely to be younger, male, had longer index hospitalization (> 5 d), Medicare and Medicaid insurance, Diabetes, and ≥ 4 Elixhauser comorbidities. Figure 2 shows independent predictors of 30-d readmission. Younger age, male patient, diabetes, parenteral nutrition, ≥ 4 Elixhauser comorbidities, longer hospital stay (> 5 d), large and metropolitan hospital, and Medicaid insurance were associated with increased hazards of 30-d readmissions. Gastric surgery, routine discharge and private insurance were associated with lower 30-d readmissions.

| Patient characteristics | 30-d readmission | ||

| Non (%)22007 (73.2%) | Yesn (%)8057 (26.8%) | P | |

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 50.1 (17.2) | 48 (16.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Age category, n (%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| 18-44 yr | 8766 (39.8) | 3658 (45.4) | |

| > 45 yr | 13241 (60.2) | 4399 (54.6) | |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.1590 | ||

| Male | 5625 (25.6) | 2124 (26.4) | |

| Female | 16382 (74.4) | 5933 (73.6) | |

| Length of stay in days, mean (SD) | 4.8 (5.2) | 5.6 (6.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Length of stay > 5 d | 5843 (26.6) | 2734 (33.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 4610 (20.9) | 1998 (24.8) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 161 (0.7) | 73 (0.9) | 0.1270 |

| Enteral feeding tube placement | 704 (3.2) | 293 (3.6) | 0.0605 |

| Jejunostomy | 445 (2.0) | 168 (2.1) | |

| Gastrostomy | 185 (0.8) | 84 (1.0) | |

| Both jejunostomy and gastrostomy | 74 (0.3) | 41 (0.5) | |

| Gastric surgery | 495 (2.2) | 97 (1.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Partial gastrectomy | 231 (1.0) | 54 (0.7) | |

| Pyloroplasty | 223 ( 1.0) | 32 (0.4) | |

| Other (total gastrectomy, pyloromyotomy) | 41 (0.2) | 11 (0.1) | |

| Total parenteral nutrition | 753 (3.4) | 380 (4.7) | < 0.0001 |

| Number of Elixhauser comorbidities | < 0.0001 | ||

| < 4 | 14302 (65.0) | 4562 (56.6) | |

| ≥ 4 | 7705 (35.0) | 3495 (43.4) | |

| Elixhauser readmission index | 17.6 (13.7) | 21.3 (14.6) | < 0.0001 |

| mean (SD) | |||

| Total cost for index admission | $10502/$7573 | $13126/$7760 | < 0.0001 |

| mean/median (IQR) | ($4880-$11858) | ($4810-$13750) | |

| Primary payer, n (%)1 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Medicare | 8855 (40.3) | 3335 (41.5) | |

| Medicaid | 3770 (17.2) | 1811 (22.5) | |

| Private | 7039 (32.1) | 2108 (26.2) | |

| Self-pay, no charge, other | 2285 (10.4) | 787 (0.8) | |

| Income quartiles n (%)2 | 0.1100 | ||

| 1st quartile | 6968 (32.2) | 2636 (33.3) | |

| 2nd quartile | 5668 (26.2) | 2023 (25.5) | |

| 3rd quartile | 5029 (23.2) | 1882 (23.7) | |

| 4th quartile | 3970 (18.3) | 1386 (7.5) | |

| Discharge disposition, n (%)3 | < 0.0001 | ||

| Discharged home (routine discharge) | 18041 (82.0) | 6217 (77.2) | |

| Transfer: Short-term hospital | 113 (0.5) | 45 (0.6) | |

| Transfer: Other type of facility | 1184 (5.4) | 393 (4.9) | |

| Home health care | 2236 (10.2) | 1186 (14.7) | |

| Against medical advice | 431 (2.0) | 216 (2.7) | |

| Hospital characteristics | |||

| Hospital control, n (%) | 0.0460 | ||

| Government nonfederal | 3014 (13.7) | 1070 (13.3) | |

| Private (not-for-profit) | 14523 (66.0) | 5247 (65.1) | |

| Private investor owned | 4470 (20.3) | 1740 (21.6) | |

| Bed size, n (%) | 0.0070 | ||

| Small | 2115 (9.6) | 692 (8.6) | |

| Medium | 5577 (25.3) | 1993 (24.7) | |

| Large | 14315 (65.0) | 5372 (66.7) | |

| Teaching status, n (%) | < 0.0001 | ||

| Metropolitan non-teaching | 9204 (41.8) | 3379 (41.9) | |

| Metropolitan teaching | 10975 (49.9) | 4161 (51.6) | |

| Non-metropolitan | 1828 (8.3) | 517 (6.4) | |

The rate of 30 and 90-d care fragmentation is shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. Of all 30-d readmissions, 28.1% of patients were readmitted to a non-index hospital, while 22% of patients were readmitted exclusively to a non-index hospital (which represents underestimation of readmission). Corresponding numbers for 90-d period are 33.8% and 19.5%, respectively.

| Time | % Readmission (No/total No) | % Underestimation of readmission (No/total No) | % Fragmentation of care (No/total No.) |

| 30-d | 26.8% (8057/30064) | 22% (1769/8057) | 28.1%(2260/ 8057) |

| 90-d | 45.6% (11987/26284) | 19.5%( 2334/11987) | 33.8%( 4049/11987) |

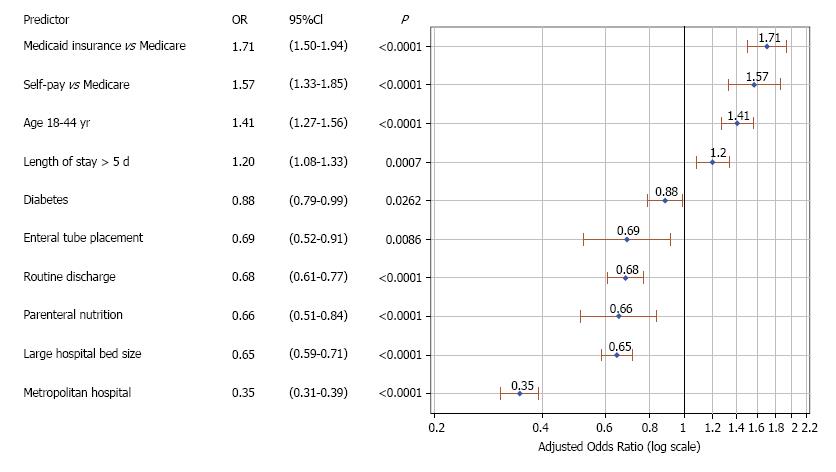

Figure 4 shows independent predictors of care fragmentation during the first 30-d readmission. Younger age, longer hospital stay (> 5 d), self-pay or Medicaid insurance were associated with increased risk of 30-d care fragmentation. Diabetes, enteral tube placement, parenteral nutrition, large metropolitan hospital, and routine discharge were associated with lower odds of readmission to a non-index hospital during the first 30-d readmission.

Outcomes of patients with and without care fragmentation during the first 30-d readmission are shown in Table 4. Patients readmitted to a non-index hospital had a longer mean hospital stay (6.5 vs 5.8 d, P = 0.03), and higher mean hospitalization costs ($15645 vs $12311, P < 0.0001) compared to those who were readmitted to the same index hospital. There were no differences in mortality (1.3% vs 1.0%, P = 0.84), or subsequent 60-d readmission rate (55.3% vs 54.6%, P = 0.99) between the two groups.

| 30-d first readmission | ||||

| Readmission to index hospital | Readmission to non-index hospital | Comparison | P | |

| Total cost for first readmission, mean/median (IQR) | $12311/$7508 | $15645/$8598 | Difference in cost: 3803$ (2777-4829)1 | < 0.0001 |

| ($4659-$13204) | ($5281-$15472) | |||

| Length of stay in days, mean (SD) | 5.8 (6.5) | 6.5 (8.2) | Adjusted HR (95%CI): 1.07 (1.01-1.13)2 | 0.03 |

| In-hospital Mortality | 1.30% | 1.00% | Adjusted OR (95%CI): | 0.84 |

| 0.95 (0.57-1.57)3 | ||||

| 60-d readmission | 54.60% | 55.30% | Adjusted HR (95%CI): 0.99 (0.94-1.06)4 | 0.99 |

Patients with gastroparesis develop chronic symptoms of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weight loss. Refractory and severe symptoms can lead to recurrent hospitalizations. In this study, we found that the readmission rate for gastroparesis is substantial (26.8% at 30 d and 45.6% at 90 d), and that several clinical, demographic and hospital factors are associated with readmission in gastroparesis. Patients with multiple comorbidities and long initial hospitalization have a higher risk of readmission. Longer length of stay was found to be independently associated with increased risk of 30-d readmission. This could be reflective of the severity of gastroparesis symptoms independent of comorbidities, which were controlled for in the model. Younger patients (age 18-44) had a higher risk of readmission compared to older ones. A prospective observational study of 262 gastroparesis patients treated at 7 tertiary referral centers reported that patients older than 50 years were more likely to have symptom improvement compared to younger patients (OR: 3.35, 94%CI: 1.62-6.91, P = 0.001)[18]. It is unclear why younger patients tend to do worse than older ones, but it could be related to better adaptation and tolerance of older patients to their medical illness[18]. Diabetes was associated with increased risk of readmissions, which could be related to complications of diabetes and not necessarily to the severity of gastroparesis. The aforementioned study did not find a difference in symptoms improvement between diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis[18]. Medicaid insurance was associated with increased risk of readmissions compared to Medicare, while private insurance was associated with lower risk. No previous study examined the relationship of insurance status with gastroparesis readmissions. A report published by the AHRQ analyzed trends of hospital readmission for all illnesses by insurance type, and found that Medicare was associated with the highest risk, followed by Medicaid, self-pay/uninsured, and private insurance[19]. One possible explanation is that Medicare patients are older and have more comorbidities than patients with other types of insurance. In our study, we controlled for age and other variables, and found that Medicaid was associated with higher readmission. This could be partly related to the several social and economic challenges facing this patient population, which precludes adequate outpatient follow-up and compliance with treatment[20]. Large, metropolitan hospitals were associated with increased readmission risk. A small percentage of patients in our study underwent gastric surgery during their admission for gastroparesis (2%), and this was associated with lower 30-d readmissions. This is consistent with few previous studies in which pyloroplasty and partial gastrectomy resulted in symptom improvement in selected patients with gastroparesis[21,22]. We did not find a benefit of gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube placement on readmission rates for gastroparesis. There are limited data on the benefit of gastric and enteral tubes in gastroparesis. A systematic review of 5 small studies evaluating gastrostomy (n = 26) and jejunostomy (n = 32) found that these treatments decrease symptoms of nausea and vomiting, although jejunostomy was associated with significant complications[23]. Parenteral nutrition is used in patients with refractory symptoms, malnutrition, and inability to tolerate enteral feeding. Despite its nutritional benefits, we found that parenteral nutrition was associated with increased hospital readmission. This could be related to the increased risk of infectious and metabolic complications. These patients require close monitoring and care to prevent complications and readmissions.

We found that 28%-34% of readmissions occur at a different (non-index) hospital. This suggests that examining readmission rates using institutional databases is insufficient, and leads to underestimation of readmissions by 22%. When gauging the efficacy of therapeutic interventions (such as drug therapy, Botulinum toxin injection, transpyloric stent, gastric per-oral endomyotomy), both index and non-index hospital readmissions should be measured. This is particularly important in single-arm, retrospective evaluations in which it is not possible to conduct a thorough patient follow-up. Measuring non-index readmissions can be done by linking hospital or insurance databases, or conducting regular telephone interviews. We identified several predictors of 30-d care fragmentation in gastroparesis. Self-pay/uninsured patients and Medicaid beneficiaries had higher likelihood of care fragmentation. Large, metropolitan hospitals were associated with decreased care fragmentation. As such, it appears that despite a higher risk of readmission in large metropolitan hospitals, patients are more likely to return to these facilities compared to smaller, non-metropolitan hospitals.

We found that care fragmentation in gastroparesis leads to higher readmission length of stay and overall costs (Table 4). This could be related to inefficient and redundant workup, such as radiologic and endoscopic procedures. In the ambulatory setting, one study found that patients with fragmented care received twice as many radiologic and diagnostic tests compared to patients with least fragmented care[24]. Currently, there is national emphasis on inter-operability of electronic health record (EHR) systems. Medicare and Medicaid EHR programs created incentives for healthcare systems to utilize EHRs that are capable of providing patients copies of their medical records, and of exchanging information between different EHR systems regardless of the vendor[25]. Once these EHRs are in place, it is possible that the availability of medical records to all providers across hospitals could partially mitigate the higher costs of fragmented care. We did not find a difference in mortality and in 60-d readmission rate following the first readmission between patients who were readmitted to an index and non-index hospital. This suggests that addressing care fragmentation in gastroparesis could reduce healthcare costs but does not change the natural history or morbidity of the disease. Other studies conducted on patients with heart failure and other critical illnesses found higher mortality in patients admitted to a non-index hospital[12,26,27].

Our study has several strengths. It is the largest study to estimate the rate of hospital readmissions in patients admitted with gastroparesis, and the only one to study care fragmentation in this disease. We used statewide data to track discharges within states across different hospitals, and then calculate the rate of underestimation of care if only institutional databases are used. In addition, this is the only study that evaluates the predictors of readmission and care fragmentation in a large nationally representative sample.

There are several limitations to this analysis. The NRD, similar to most other hospital administrative databases, does not contain important clinical parameters such as medications, laboratory values, and imaging studies. Therefore, we cannot categorize the severity and etiology of gastroparesis using this database, nor analyze clinical predictors of outcomes in gastroparesis. We tried to adjust for predictors of care fragmentation; however, other factors play a role in non-index hospitalizations. These include patients’ preference, place of residence and proximity to the index hospital. These should be taken into account in planning post discharge follow-up.

In conclusion, patients with gastroparesis are prone to frequent hospital admissions. Our study highlights the high readmission and care fragmentation rates in gastroparesis, and identifies several predictors of these outcomes. Post discharge care coordination that focuses on high-risk patients could reduce hospital readmission and fragmentation of care, leading to improved quality of life and lower overall costs of care.

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder that can lead to debilitating symptoms resulting in recurrent hospitalizations. These hospital admissions can be costly, especially if the patient is admitted repeatedly to different hospitals. Hospital readmissions can be underestimated if non-index readmissions (i.e., readmissions to a different hospital) are not captured during follow up.

Knowledge of the predictors of hospital readmissions can help design interventions that focus on high risk factors. Estimating the rate of care fragmentation provides further insight into the burden of gastroparesis on patients and the healthcare system. It also highlights the need to refine the methods to calculate hospital readmission.

The study aims to evaluate the rate of hospital readmissions in gastroparesis, and to estimate the proportion of readmissions to index and non-index hospitals (care fragmentation). We also sought to study factors related to readmission and care fragmentation, and their effect on future outcomes such as length of stay, costs, mortality, and readmissions.

We used the national readmission database to identify all adult admissions with primary diagnosis of gastroparesis. We calculated the rate of 30 and 90-d statewide hospital readmissions and care fragmentation. We analyzed factors related to hospital readmission and care fragmentation using multivariable models.

We found a high rate of hospital readmission in gastroparesis (26.8% at 30 d and 45.6% at 90 d). Around one fourth of readmissions occur at a different hospital, and 20% occur exclusively at a different hospital. This means that 20% of all 30-d readmissions will not get captured if local hospital databases are used to track patients. Readmission to a different hospital within 30-d was associated with higher hospitalization costs and length of stay. We identified several sociodemographic and clinical factors that are associated with hospital readmission and care fragmentation. Gastric surgery is associated with decreased risk of readmission, while enteral tube insertions (gastrostomy or jejunostomy) did not affect readmissions.

This is the first population based study to highlight the high rate of hospital readmission and care fragmentation in gastroparesis. It is also the first to report several sociodemographic and clinical factors related to these outcomes, which can be used to identify high-risk patients.

In addition to reducing hospital readmissions, hospitals should also attempt to decrease care fragmentation because it is associated with increased costs of care. Hospital readmissions are a major cause of morbidity in gastroparesis. Trials involving different interventions for gastroparesis should also evaluate the effect of these interventions on reducing hospital readmissions.

| 1. | Jung HK, Choung RS, Locke GR 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Szarka LA, Mullan B, Talley NJ. The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1225-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 474] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Wadhwa V, Mehta D, Jobanputra Y, Lopez R, Thota PN, Sanaka MR. Healthcare utilization and costs associated with gastroparesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:4428-4436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Woodhouse S, Hebbard G, Knowles SR. Psychological controversies in gastroparesis: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:1298-1309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Teigland T, Iversen MM, Sangnes DA, Dimcevski G, Søfteland E. A longitudinal study on patients with diabetes and symptoms of gastroparesis - associations with impaired quality of life and increased depressive and anxiety symptoms. J Diabetes Complications. 2018;32:89-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hasler WL, Parkman HP, Wilson LA, Pasricha PJ, Koch KL, Abell TL, Snape WJ, Farrugia G, Lee L, Tonascia J. Psychological dysfunction is associated with symptom severity but not disease etiology or degree of gastric retention in patients with gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2357-2367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Talley NJ, Young L, Bytzer P, Hammer J, Leemon M, Jones M, Horowitz M. Impact of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in diabetes mellitus on health-related quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Uppalapati SS, Ramzan Z, Fisher RS, Parkman HP. Factors contributing to hospitalization for gastroparesis exacerbations. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:2404-2409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bielefeldt K. Factors influencing admission and outcomes in gastroparesis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:389-398, e294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schrag D, Xu F, Hanger M, Elkin E, Bickell NA, Bach PB. Fragmentation of care for frequently hospitalized urban residents. Med Care. 2006;44:560-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zheng C, Habermann EB, Shara NM, Langan RC, Hong Y, Johnson LB, Al-Refaie WB. Fragmentation of Care after Surgical Discharge: Non-Index Readmission after Major Cancer Surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222:780-789.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Justiniano CF, Xu Z, Becerra AZ, Aquina CT, Boodry CI, Swanger A, Temple LK, Fleming FJ. Long-term Deleterious Impact of Surgeon Care Fragmentation After Colorectal Surgery on Survival: Continuity of Care Continues to Count. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:1147-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McAlister FA, Youngson E, Kaul P. Patients With Heart Failure Readmitted to the Original Hospital Have Better Outcomes Than Those Readmitted Elsewhere. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:pii: e004892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chappidi MR, Kates M, Stimson CJ, Bivalacqua TJ, Pierorazio PM. Quantifying Nonindex Hospital Readmissions and Care Fragmentation after Major Urological Oncology Surgeries in a Nationally Representative Sample. J Urol. 2017;197:235-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | HCUP. Introduction to HCUP Nationwide Readmission Database. Healthcare Cost and Utili-zation Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016. Accessed on August 17, 2017. Available from: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2010-2014.pdf. |

| 15. | HCUP. NRD description of data elements. Healthcare Cost and Utili-zation Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016. Accessed on August 17, 2017. Available from: www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/nrddde.jsp. 2016. |

| 16. | Spanier BW, Dijkgraaf MG, Bruno MJ. Trends and forecasts of hospital admissions for acute and chronic pancreatitis in the Netherlands. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:653-658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L; American College of Gastroenterology. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-37; quiz 38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 824] [Cited by in RCA: 776] [Article Influence: 59.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Pasricha PJ, Yates KP, Nguyen L, Clarke J, Abell TL, Farrugia G, Hasler WL, Koch KL, Snape WJ, McCallum RW. Outcomes and Factors Associated With Reduced Symptoms in Patients with Gastroparesis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1762-1774.e1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Barrett ML, Wier LM, Jian J, Steiner CA. All-Cause Readmissions by Payer and Age, 2009-2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #199. December 2015. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb199-Readmissions-Payer-Age.pdf. |

| 20. | Hospital Guide to Reducing Medicaid Readmissions. (Prepared by Collaborative Healthcare Strategies, Inc., and John Snow, Inc., under Contract No. HHSA290201000034I). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; August 2014. AHRQ Publication No. 14-0050-EF. . |

| 21. | Hibbard ML, Dunst CM, Swanström LL. Laparoscopic and endoscopic pyloroplasty for gastroparesis results in sustained symptom improvement. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1513-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Watkins PJ, Buxton-Thomas MS, Howard ER. Long-term outcome after gastrectomy for intractable diabetic gastroparesis. Diabet Med. 2003;20:58-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jones MP, Maganti K. A systematic review of surgical therapy for gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2122-2129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kern LM, Seirup JK, Casalino LP, Safford MM. Healthcare Fragmentation and the Frequency of Radiology and Other Diagnostic Tests: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:175-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | The Centers for Medicare Medicaid Services. Electronic Health Records Incentive Programs, 2017. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms. |

| 26. | Hua M, Gong MN, Miltiades A, Wunsch H. Outcomes after Rehospitalization at the Same Hospital or a Different Hospital Following Critical Illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1486-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Havens JM, Olufajo OA, Tsai TC, Jiang W, Columbus AB, Nitzschke SL, Cooper Z, Salim A. Hospital Factors Associated With Care Discontinuity Following Emergency General Surgery. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Huerta-Franco MR, Tseng PH S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H