Published online May 16, 2018. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v10.i5.83

Peer-review started: January 31, 2018

First decision: February 27, 2018

Revised: March 4, 2018

Accepted: March 20, 2018

Article in press: March 20, 2018

Published online: May 16, 2018

Processing time: 106 Days and 6.4 Hours

To investigate factors associated with the healing of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)-induced ulcers.

We enrolled 132 patients with gastric tumors scheduled for ESD. Following ESD, patients were treated with daily lansoprazole 30 mg or vonoprazan 20 mg. Ulcer size was endoscopically measured on the day after ESD and at 4 and 8 wk. The gastric mucosa was endoscopically graded according to the Kyoto gastritis scoring system. We assessed the number of patients with and without a 90% reduction in ulcer area at 4 wk post-ESD and scar formation at 8 wk, and looked for risk factors for slower healing.

The mean size of gastric tumors and post-ESD ulcers was 17.4 ± 12.1 mm and 32.9 ± 13.0 mm. The mean reduction rates in ulcer area were 90.4% ± 0.8% at 4 wk and 99.8% ± 0.1% at 8 wk. The reduction rate was associated with the Kyoto grade of gastric atrophy at 4 wk (A0: 97.9% ± 0.6%, A1: 93.4% ± 4.1%, and A2: 89.7% ± 1.0%, respectively). In multivariate analysis, the factor predicting 90% reduction at 4 wk was gastric atrophy (Odds ratio: 5.678, 95%CI: 1.190-27.085, P = 0.029).

The healing speed of post-ESD ulcers was associated with the degree of gastric mucosal atrophy, and Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is required to perform at younger age.

Core tip: It is important to investigate factors influencing the healing speed of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)-induced ulcers to prevent gastrointestinal bleeding. Although previous studies have looked at many factors related to ESD-induced ulcer healing, such as location of the tumor, submucosal fibrosis, initial ulcer size, diabetes, and method of gastric acid suppression, this report showed that the severity of gastric atrophy is possible factor to affect speed of ESD-induced ulcer healing. Therefore, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication therapy is required to perform at younger age before progression of gastric mucosal atrophy to prevent development of H. pylori-related diseases and bleeding from ESD-induced ulcer.

- Citation: Otsuka T, Sugimoto M, Ban H, Nakata T, Murata M, Nishida A, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Andoh A. Severity of gastric mucosal atrophy affects the healing speed of post-endoscopic submucosal dissection ulcers. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10(5): 83-92

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v10/i5/83.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v10.i5.83

The efficacies of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) and surgical gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer are generally similar[1]. ESD, being less invasive, is the first-line treatment for early-stage gastric cancer. ESD allows en bloc resection and is associated with a lower recurrence rate than endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)[2,3].

Gastrointestinal bleeding from ESD-induced ulceration is a common complication[4-7]. Factors associated with an increased risk of post-ESD gastrointestinal bleeding include the size, location, and histology of the gastric cancer; kinds of gastric acid suppressant; patient use of dialysis; and long procedure time[4-7]. The risk of bleeding is reduced by endoscopic coagulation of exposed vessels at the base of ESD-induced ulcers and potent acid inhibition over the first 24 h post-treatment[4-7]. When ESD is performed for gastric cancer, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are used to treat ESD-induced ulcers[7]. However, PPIs may not suppress gastric acid secretion over 24 h, especially at night. Administration is required over several days to maximize gastric acid inhibition. More recently, interindividual genetic variations (e.g., CYP2C19 genotype)[8,9] have been linked to different metabolism rates of PPIs. Vonoprazan, a potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB) with more potent and sustained acid inhibition than PPIs, has been approved in Japan[10-12]. Although vonoprazan inhibits gastric H+/K+-ATPase similarly to PPIs, its mechanism of acid inhibition involves inhibition of H+, K+-ATPase by binding reversibly and competitively with K+[13]. It remains unclear whether vonoprazan is associated with improved ulcer healing speed and prevention of post-ESD bleeding, due to the low statistical power of the most recent studies[5,14].

Previous studies have looked at many factors related to ESD-induced ulcer healing, such as location of the tumor[15], submucosal fibrosis[16], initial ulcer size[17,18], diabetes[18], coagulation abnormality[18], electrocoagulation during ESD[18], and method of gastric acid suppression[19].

Concurrent Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection has been found to influence the speed of peptic ulcer healing[20,21]. However, it is unclear whether current H. pylori infection and eradication therapy affect the healing of ESD-induced ulcers[22,23]. In addition, there may be an association with the severity of gastritis/gastric atrophy and post-ESD ulcer healing[23,24].

Rapid healing of ESD-induced ulcers is key to the prevention of delayed bleeding. We investigated factors that might be associated with healing of post-ESD ulcers, including H. pylori status, profile of the gastric tumor, kinds of acid inhibitory drugs, and severity of gastritis (e.g., gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia).

We enrolled 132 Japanese patients who underwent ESD for clinical early-stage gastric cancer and adenoma between March 2013 and October 2016 at our institution. Approval for the study protocol was given in advance by the Institutional Review Board of the Shiga University of Medicine Science (Number 27-36). This trial was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network, UMIN000018188.

ESD was performed if cases met the following criteria of early-stage gastric cancer and gastric adenoma according to the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer stages: (1) Intramucosal intestinal-type neoplasm without ulceration, regardless of tumor size; (2) intramucosal intestinal-type cancer with ulceration, ≤ 3 cm; (3) intestinal-type cancer invading the submucosa < 500 μm from the muscularis mucosa, ≤ 3 cm in size; and (4) intramucosal diffuse-type cancer without ulceration, ≤ 2 cm. Exclusion criteria were patients with advanced-stage gastric cancer, patients who refuse follow-up endoscopy at both 4 and 8 wk after ESD treatment and patients with lack of informed consent.

Although severity of anemia and oxygenation were expected to affect the healing speed of ESD-induced ulcer, there were no patients with severe anemia of less than 10 g/mL or hypoxemia.

For this study, we enrolled patients who had undergone ESD for resection of gastric tumor and provided blood samples for an anti-H. pylori IgG serological testing and CYP2C19 genotyping. The endoscopic severity of gastritis was characterized by the Kyoto classification[25]. According to the Kyoto classification of gastritis, patients are scored according to atrophy (None: A0, atrophic patterns with a margin between the non-atrophic fundic mucosa and atrophic mucosa located in the lesser curvature of the stomach: A1, and atrophic patterns, whose margin does not cross the lesser curvature: A2), intestinal metaplasia (none: IM0, within antrum: IM1, and up to corpus: IM2), hypertrophy of gastric folds (negative: H0, positive: H1), and diffuse redness (negative: DR0, mild: DR1, severe: DR2)[25].

ESD was performed with a single-channel magnifying endoscope (GIF-H290Z or GIF-H260Z; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). We used a fixed-length disc-tipped knife (Dual knife®, KD-650L/Q; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or an insulated-tip diathermic knife (IT knife 2®, KD-611L, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) and applied electric current using an electrosurgical generator (VIO300D®; ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany). Visible vessels were heat-coagulated using hemostatic forceps (FD-412LR®; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). After ESD, 73.5% of patients were dosed with lansoprazole 30 mg and 26.5% were dosed with vonoprazan 20 mg (Table 1) for 8 wk.

| Parameter | |

| Number | 132 |

| Age (yr) | 71.0 ± 8.6 |

| Gender (male/female) | 100/32 (75.8%/34.2%) |

| H. pylori status (positive/negative) | 68/64 (51.5%/48.5%) |

| Anti-coagulant administration (+/-) | 22/110 (16.7%/83.3%) |

| Acid suppressant post-ESD (lansoprazole/vonoprazan) | 97/35 (73.5%/26.5%) |

| CYP2C19 genotype (EM/IM/PM) | 40/51/22 (35.4%/45.1%/19.5%) |

| Endoscopic background of gastric mucosa | |

| Atrophy (Kyoto A0+A1/Kyoto A2) | 20/112 (15.2%/84.8%) |

| Intestinal metaplasia (none + mild/severe) | 72/55 (56.7%/43.3%) |

| Diffuse redness (none/mild/severe) | 65/62 (51.2%/48.8%) |

| Tumor | |

| Types (adenoma/cancer) | 16/116 (12.1%/87.9%) |

| Depth (mucosa/submucosa) | 118/14 (89.4%/10.6%) |

| Location of tumors (upper/middle/lower third) | 15/67/50 (11.4%/50.8%/37.8%) |

| ESD | |

| Mean procedure time (min) | 76.4 ± 56.7 |

| Mean resected ulcer area (mm2) | 671.9 ± 720.9 |

| ESD-induced ulcer area | |

| Reduction at 4 wk | 90.4% ± 10.7% |

| Mean ulcer area at 4 wk (mm2) | 71.3 ± 135.6 |

| Reduction at 8 wk | 99.8% ± 0.6% |

| Mean ulcer area at 8 wk (mm2) | 2.8 ± 15.6 |

The major and minor axes of ESD-induced ulcers were endoscopically measured the day after ESD by measurement forceps (M2-4K®; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), and at 4 and 8 wk post-ESD.

Infection status of H. pylori was evaluated based on findings from two tests: an anti-H. pylori IgG serological test (E plate Eiken H. pylori antibody®; Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd., Tochigi, Japan) and a rapid urease test (Helicocheck®; Otsuka Co., Tokyo, Japan). When either test was positive, the patient was diagnosed as positive for H. pylori infection.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the blood (DNA Extract All Reagents®, Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA, United States). Subsequently, genotyping was performed using a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping assay (TaqMan®, Applied Biosystems) in a real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) system (Step One Plus®, Applied Biosystems). Genotyping for identifying the CYP2C19 wild-type gene and two mutated alleles, CYP2C19 *2 (rs4244285, A/G) and *3 (rs-4986893, G/A) were performed to classify each subject as belonging to one of the following four genotype groups: extensive metabolizers (EMs, * 1/ * 1), intermediate metabolizers (IMs; * 1/ * 2 or * 1/ * 3), or poor metabolizers (PMs; * 2/ * 2, * 2/ * 3 or * 3/ * 3).

Age, ESD procedure time and ESD-induced ulcer area are expressed as mean ± SD. The healing rates of ulcers were calculated as (1-ulcer area/ulcer area just after ESD) × 100 (%) and are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical differences in these parameters among CYP2C19 genotypes; between H. pylori infection statuses; among degrees of atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and diffuse redness according to the Kyoto classification; and among tumor locations were determined using one-way ANOVA with Scheffé multiple comparison and Fisher’s exact tests. All P values are two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Calculations were performed using commercial software (SPSS version 20, IBM Inc; Armonk NY, United States).

The mean procedure time was 76.4 ± 56.7 min and the mean resected ESD-induced ulcer area was 671.9 ± 720.9 mm2 at Day 1. Procedure time for lesions in the lower third of the stomach (47.5 ± 3.2 min) was significantly shorter than those for the middle and upper thirds [vs middle (85.7 ± 6.6 min), P = 0.001, vs upper (131.3 ± 17.9 min), P < 0.001, respectively]. The initial ulcer area in the lower third (456.4 ± 265.2 mm2) was significantly smaller than that of the middle third (822.0 ± 922.2 mm2, P = 0.008).

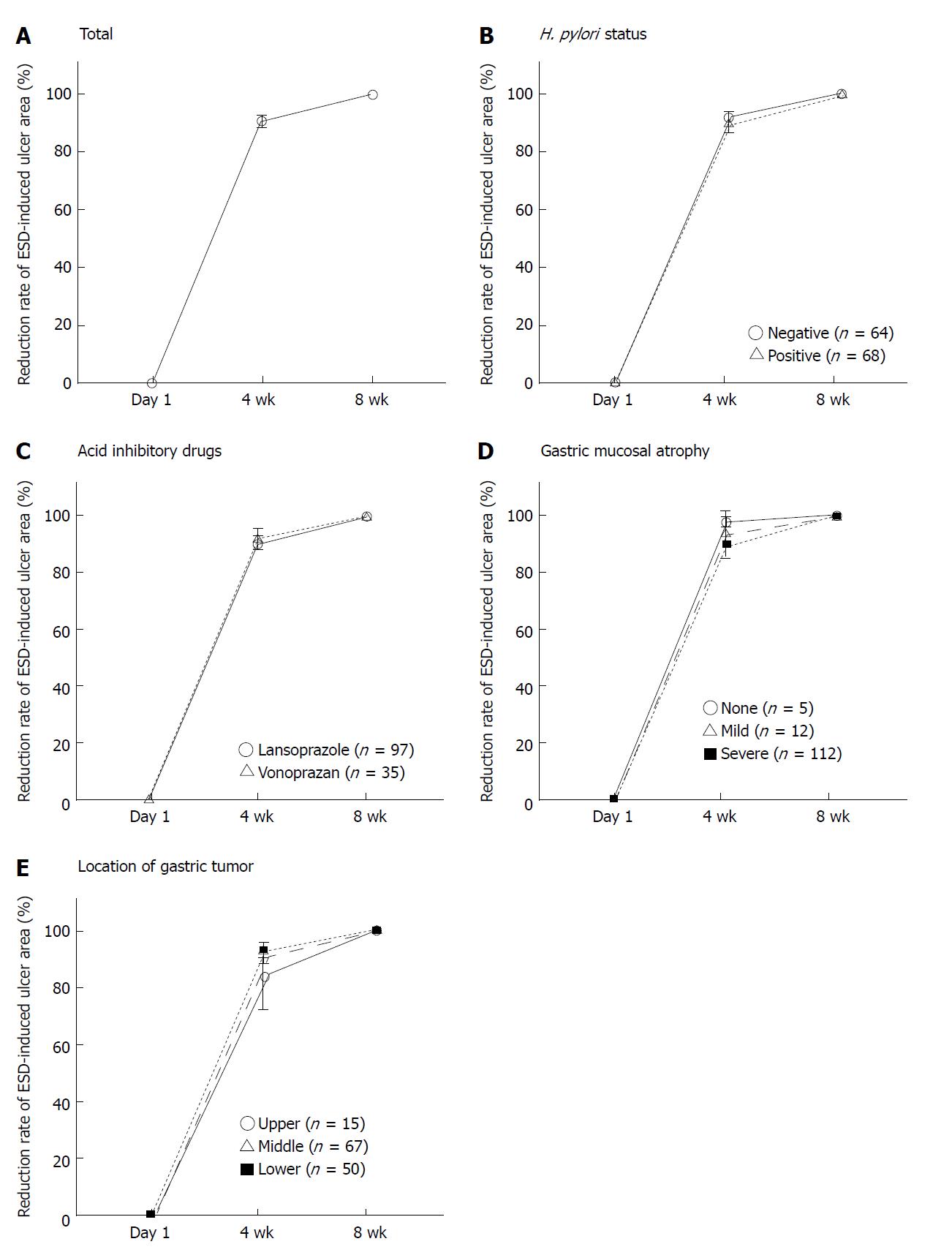

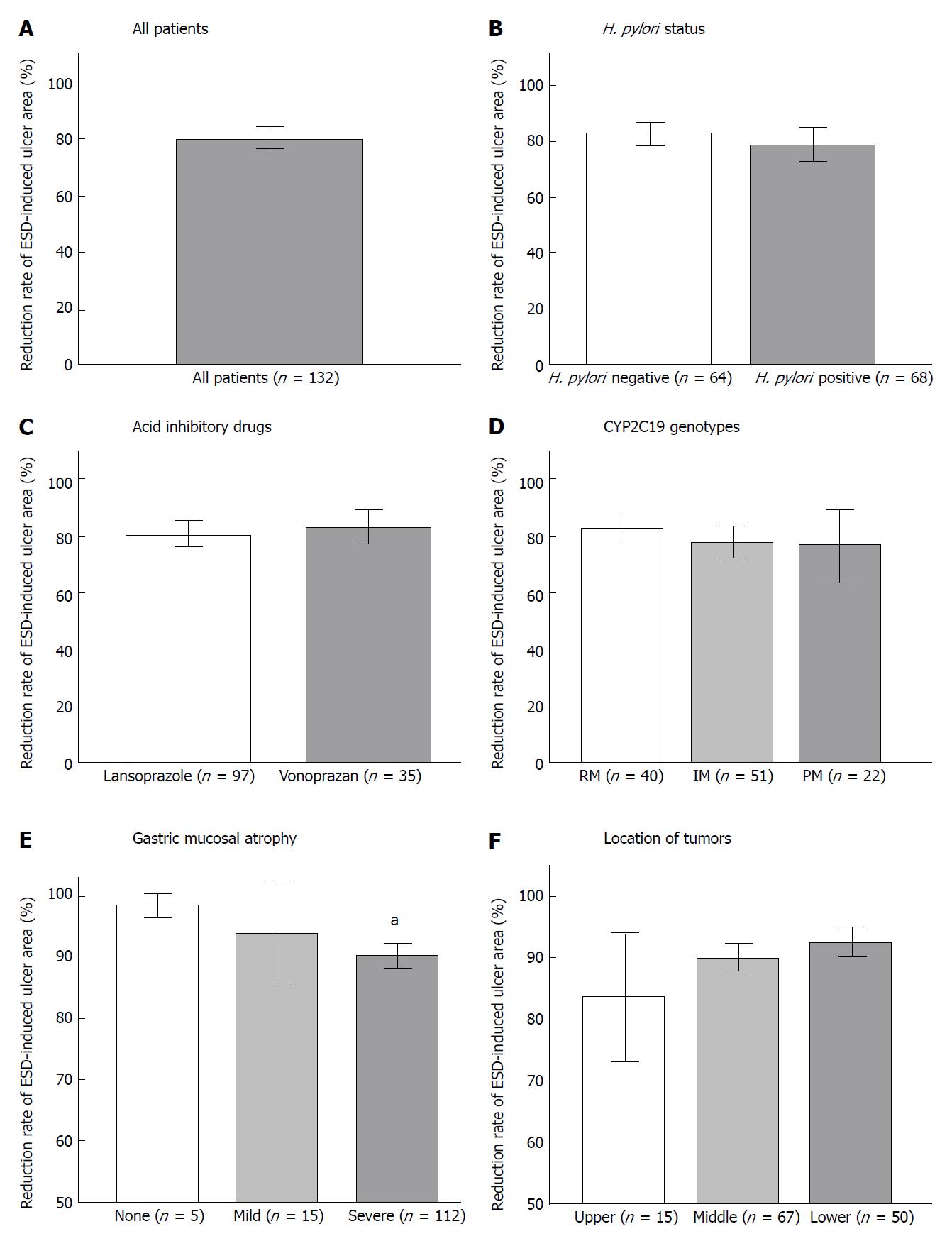

After ESD, mean ESD-induced ulcer areas at 4 and 8 wk were 71.3 ± 135.6 mm2 and 2.8 ± 15.6 mm2, respectively, and mean healing rates were 90.4% ± 0.8% at 4 wk and 99.8% ± 0.1% at 8 wk (Figures 1A and 2A). At 8 wk, mean healing rate in the H. pylori-positive group (99.7% ± 0.1%) was significantly lower than that in the negative group (99.9% ± 0.0%, P = 0.035). There were no significant differences between mean healing rates for lansoprazole and vonoprazan treatment at 4 and 8 wk (Figures 1B and C, 2B and C).

Healing rate was associated with the severity of gastric atrophy at 4 wk (A0: 97.9% ± 0.6%, A1: 93.4% ± 4.1%, and A2: 89.7% ± 1.0%, respectively).

In patients with severe gastric atrophy, the healing rate was significantly lower than that in patients with mild or no atrophy (A0 + A1) (P < 0.001 and P = 0.010) (Figures 1D and 2E). In addition, at 4 wk, the mean healing rate in the lower third (92.8% ± 1.2%) was significantly delayed compared to the upper two-thirds (83.7% ± 5.3%, P = 0.013) (Figure 1E and 2F). After 8 wk, ESD-induced ulcers were scarred in 85.7% (12/14) in the upper third, 89.2% (58/65) of the middle third, and 83.3% (40/48) of the lower third (P = 0.657) of the stomach. There was no significant association of healing rates at 4 wk with CYP2C19 genotypes (Figure 2D).

We investigated the healing rate of ESD-induced ulcers by setting up over 90% of ESD-induced ulcer area at 4 wk and 100% at 8 wk. ESD-induced ulcers with ≥ 90% healing at 4 wk were associated with absence of atrophy (P = 0.010), depth of gastric tumor (P = 0.004), and procedure time P = 0.026) (Table 2). The mean procedure time in the ≥ 90% healing group was significantly shorter than that in the < 90% healing group (65.6 ± 41.1 min vs 89.7 ± 64.0 min, P = 0.026). The prevalence of patients with open-type atrophic gastritis in the ≥ 90% healing group was 78.0% (64/82), which was significantly lower than that in the < 90% healing group (96.0%, 43/45, P = 0.01).

| Reduction rate over 90% at 4 wk | Reduction rate 100% at 8 wk | |||||

| Characteristic | Achieved (n = 82) | Not achieved (n = 45) | P value | Achieved (n = 110) | Not achieved (n = 16) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 70.9 ± 9.3 | 71.2 ± 7.3 | 0.831 | 70.4 ± 8.9 | 74.1 ± 6.2 | 0.047 |

| Gender (male/female) | 62/20 (75.6%/24.4%) | 33/12 (73.3%/26.7%) | 0.777 | 86/24 (78.2%/21.8%) | 8/8 (50.0%/50.0%) | 0.021 |

| H. pylori (positive/negative) | 42/40 (51.2%/48.8%) | 24/21 (53.3%/46.7%) | 0.82 | 54/56 (49.1%/50.9%) | 12/4 (75.0%/25.0%) | 0.053 |

| Anti-coagulants | 13 (15.9%) | 8 (17.8%) | 0.78 | 16 (14.5%) | 4 (25.0%) | 0.231 |

| PPI or PCAB (post-ESD) | 60/22 (73.2%/26.8%) | 32/13 (71.1%/28.9%) | 0.804 | 82/28 (74.5%/25.5%) | 14/2 (87.5%/12.5%) | 0.210 |

| CYP2C19 type (EM/IM/PM) | 27/28/15 (38.6/40/21.4) | 12/20/7 (30.8/51.3/17.9) | 0.522 | 35/39/19 (37.6/41.9/20.5) | 4/9/1 (28.6%/64.3%/7.1%) | 0.249 |

| Gastric mucosa | ||||||

| Trophy (Kyoto A0+A1/Kyoto A2) | 18/64 (22.0%/78.0%) | 2/43 (4.0%/96.0%) | 0.01 | 19/91 (17.3%/82.7%) | 1/15 (6.3%/93.7%) | 0.233 |

| Metaplasia (none-mild/severe) | 51/31 (62.2/37.8) | 21/24 (46.7/53.3) | 0.091 | 64/46 (58.2/41.8) | 8/8 (50.0/50.0) | 0.537 |

| Diffuse redness (none-mild/severe) | 44/38 (53.7/46.3) | 21/24 (46.7/53.3) | 0.451 | 60/50 (54.5/45.5) | 7/9 (43.8/56.2) | 0.419 |

| Tumor | ||||||

| Depth (mucosa/submucosa) | 78/4 (95.1/4.9) | 35/10 (77.8/22.2) | 0.004 | 101/9 (91.8 /8.2) | 15/1 (93.8/6.2) | 0.629 |

| Location (upper/middle/lower third) | 7/39/36/ (8.5/47.6/43.9) | 7/26/12 (15.6/57.8/26.6) | 0.124 | 12/58/40 (10.9/52.7/36.4) | 2/7/7 (12.4/43.8/43.8) | 0.797 |

| ESD | ||||||

| Mean procedure time (min) | 65.6 ± 41.1 | 89.7 ± 64.0 | 0.026 | 73.9 ± 52.3 | 76.1 ± 41.4 | 0.872 |

| Mean resected ulcer area (mm2) | 544.7 ± 387.1 | 809.8 ± 849.8 | 0.053 | 567.3 ± 435.2 | 1178.5 ± 1520.1 | 0.130 |

In achievement of scar formation at 8 wk, the rates were associated with gender (P = 0.021) and age (P = 0.047), but not gastritis or tumor-related factors (Table 2).

In the univariate analysis to identify possible factors related to achievement of 90% healing at 4 wk, healing was associated with gastric atrophy (OR = 6.047, 95%CI: 1.334-27.403, P = 0.019), procedure time (OR = 1.009, 95%CI: 1.002-1.017, P = 0.018) and initial ESD-induced ulcer size (OR = 0.001, 95%CI: 1.000-1.001, P = 0.032) (Table 3). At 8 wk, gender and initial ESD-induced ulcer size significantly correlated with the achievement of scarring at 8 wk (P = 0.021 and P = 0.013, respectively) (Table 3).

| Reduction rate over 90% at 4 wk | Reduction rate 100% at 8 wk | |||

| Variable | Not achieved (n = 45) | P value | Not achieved (n = 16) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 1.004 (0.963-1.048) | 0.841 | 1.058 (0.987-1.135) | 0.113 |

| Gender (female vs male) | 1.127 (0.491-2.588) | 0.777 | 3.583 (1.218-10.545) | 0.021 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 1.088 (0.525-2.255) | 0.820 | 3.111 (0.945-10.244) | 0.053 |

| Lansoprazole vs vonoprazan | 1.108 (0.493-2.488) | 0.804 | 0.418 (0.089-1.956) | 0.210 |

| Anti-coagulants | 1.148 (0.436-3.018) | 0.780 | 1.958 (0.561-6.832) | 0.231 |

| CYP2C19 type (EM vs IM/PM) | 1.084 (0.635-1.850) | 0.768 | 0.921 (0.420-2.020) | 0.838 |

| Atrophy (Kyoto A0+A1 vs Kyoto A2) | 6.047 (1.334-27.403) | 0.010 | 3.132 (0.390-25.163) | 0.233 |

| Tumor located in upper and middle third (vs lower third) | 0.465 (0.211-1.026) | 0.055 | 1.361 (0.471-3.934) | 0.568 |

| Mean procedure time (min) | 1.009 (1.002-1.017) | 0.018 | 1.001 (0.991-1.011) | 0.871 |

| Mean resected ulcer area (mm2) | 1.001 (1.000-1.001) | 0.032 | 1.001 (1.000-1.001) | 0.013 |

In the multivariate analysis including gender, H. pylori infection, endoscopic severity of atrophy, tumor location, mean procedure time, and mean initial ESD-induced ulcer size, the factor associated with 90% healing at 4 wk was gastric atrophy (OR = 5.678, 95%CI: 1.190-27.085, P = 0.029) (Table 4). The factors associated with scarring at 8 wk were gender (female, OR = 4.438, 95%CI: 1.253-15.724, P = 0.021) and initial ESD-induced ulcer size (1.001, 1.000-1.002, P = 0.023) (Table 4).

| Reduction rate over 90% at 4 wk | Reduction rate 100% at 8 wk | |||

| Variable | Not achieved (n = 45) | P value | Not achieved (n = 16) | P value |

| Gender (male vs female) | 1.833 (0.715-4.698) | 0.207 | 4.438 (1.253-15.724) | 0.021 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 1.012 (0.463-2.213) | 0.976 | 3.340 (0.866-12.885) | 0.080 |

| Atrophy (Kyoto A0+A1 vs Kyoto A2) | 5.678 (1.190-27.085) | 0.029 | 2.764 (0.309-24.711) | 0.363 |

| Tumor located in upper and middle third (vs lower third) | 0.698 (0.283-1.724) | 0.436 | 1.848 (0.493-6.933) | 0.362 |

| Mean procedure time (min) | 1.007 (0.997-1.017) | 0.194 | 0.998 (0.982-1.015) | 0.850 |

| Mean resected ulcer area (mm2) | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.443 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) | 0.023 |

Two patients (1.5%) experienced delayed bleeding with tarry stool and only one patient received transfusion treatment after ESD treatment. Although the prevalence of patients received anti-coagulants was 16.7% and no cases with hematologically abnormal coagulation ability were observed (Table 1), intake of aspirin of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug did not increase incidence of gastric bleeding after ESD. There were no other major ESD-related adverse events.

The healing speed of ESD-induced ulcers may be a key factor in preventing ESD-related bleeding. In this study, we investigated possible risk factors associated with healing of ESD-induced ulcers and found that of all possible factors, severe gastric atrophy at 4 wk post-ESD and initial ulcer size at 8 wk were independent risk factors in multivariate analysis. However, we found no significant association of healing of ESD-induced ulcers and tumor location[15], initial ulcer size[17,18], coagulation abnormality[18], electrocoagulation during ESD[18], or kind of gastric acid suppressant[19]. Because the healing rate of ESD-induced ulcers was affected by tumor size, post-ESD ulcer size and severity of gastritis (e.g., gastric atrophy), attention should be paid to the incidence of complications (i.e., bleeding and perforation) in patients with severe gastric atrophy and a large size of gastric tumor.

In this study, we focused on the influence of the severity of gastric atrophy on the healing rate of ESD-induced ulcers. Previously, Fujiwara et al[24] reported improved healing at 8 wk post-ESD for patients with severe atrophic gastritis when treated concomitantly with a PPI and rebamipide. In this study, at 4 wk after ESD, we revealed that severe gastric atrophy, especially of the A2 type according to the Kyoto classification, slowed healing speed. Kakushima et al[23] failed to show a significant association between the severity of gastric atrophy and ESD-induced ulcer healing with administration with omeprazole and sucralfate for 8 wk post-ESD; our study also did not demonstrate significant differences at 8 wk post-ESD. At 8 wk, mean reduction rates were 99.8% ± 0.1% and ESD-induced ulcers were scarred in 83.3% (110/132). We therefore hypothesize that the severity of gastric atrophy may influence healing of ESD-induced ulcers at 4 wk, but not at 8 wk.

Intestinal metaplasia is often observed in patients with severe gastric atrophy and is a well-known risk factor for gastric cancer, similar to severe gastric atrophy alone. The prevalence of intestinal metaplasia in H. pylori-positive patients is 57% in Japanese aged approximately 70 years[26]. Although we saw no significant association between the severity of intestinal metaplasia and ulcer healing speed in this study, Chen et al[27] reported that patients with intestinal metaplasia had a higher healing rate of gastric ulcers than those without intestinal metaplasia, suggesting that patients with severe gastric atrophy accompanied by intestinal metaplasia should be considered as likely candidates for ESD-related complication, due to delayed ulcer healing.

In general, peptic ulcer healing has been correlated with intragastric pH[28], H. pylori infection[20], gastric motility[29], microcirculation in gastric mucosa[30-32], gastric mucosal levels of growth factors[33,34] and prostaglandins (PGs)[35]. The aggressive factors induced gastric mucosal injury resulting in loss of mucosal barrier can be quickly healed if adequate supply of PGE2, epidermal growth factor and tumor growth factor (TGF) α takes place. Although it is unclear whether peptic ulcers and ESD-induced ulcers share a similar healing mechanism, because severity of gastric mucosal atrophy reduced microcirculation in gastric mucosa and gastric mucosal levels of prostaglandin and growth factors, resulted that advanced gastric atrophy perturbs the process of ulcer healing in the presence of these above factors.

Vonoprazan has a longer half-life (7.7 h) than PPIs, due to its slow dissociation from H+/K+-ATPase[36]. In addition, vonoprazan inhibits H+/K+-ATPase activity with 400-fold greater potency than lansoprazole at pH 6.6[37]. Therefore, use of vonoprazan for treatment of ESD-induced ulcers is expected to confer an advantage over the conventional regimen with a PPI. This is despite the finding of Kagawa et al[5], who reported that the rates of ESD-related ulcer healing were 96.0% ± 6.7% at 6 wk with vonoprazan and 94.7% ± 11.6% at 8 wk with PPI, despite the fact the post-ESD bleeding incidence in the vonoprazan group (1.3%) was less than that in the PPI group (10.0%, P = 0.01). In a prospective randomized controlled trial, the rate of scar formation attained with vonoprazan at 8 wk was significantly higher than that for esomeprazole (94.9% vs 78.0%, P = 0.049), and in a multivariate analysis, only vonoprazan was correlated with scar formation (OR = 6.33; 95%CI: 1.21-33.20)[14]. However, although we have two kinds of clinical pathways scheduled to use lansoprazole or vonoprazan after ESD treatment for gastric tumors and investigated to analyze the healing speed of ulcer after ESD by use of only the two kinds of acid inhibitory drugs, lansoprazole and vonoprazan, there was no significant difference between vonoprazan and lansoprazole at 4 wk and 8 wk after ESD in this study. Given that one factor associated with healing of ESD-induced ulcers at 8 wk in multivariate analysis was initial ulcer size, this discrepancy may be due to differences in the size of lesions. Although potent acid inhibition is required to heal ESD-induced ulcers, a 90% reduction in ESD-induced ulcers was achieved at 28 d, irrespective of acid inhibitors. It is important to investigate whether the kind of acid inhibitor influences the speed of artificial ulcer reduction in an earlier phase (i.e., within 2 wk).

Several limitations of this study warrant mention. First, the sample size is not large. Second, we did not gather data regarding the reduction rate at 2 wk post-ESD. In this study, most ESD-induced ulcers had already healed by 4 wk post-ESD, which means evaluation at an earlier phase is required. Third, although we investigated the influence of CYP2C19 genotype, which impacts the pharmacodynamics of PPI, on the healing of ulcers, we did not clarify whether the CYP3A4/5 genotype, which is related to vonoprazan-dependent pharmacodynamics, influenced healing[38]. Forth, although minerals (e.g., Zn) and vitamins (e.g., Vitamin C) may affect the healing speed of ulcer after ESD, unfortunately, we have no data of minerals and vitamins in all patients[39,40].

In conclusions, we conducted a study to investigate factors influencing the healing speed of ESD-induced ulcers. Healing speed was affected by the severity of gastric atrophy, but not by H. pylori status, kinds of acid inhibitory drugs, or CYP2C19 genotype. These results suggest that eradication of H. pylori can be carried out at any time in terms of ulcer healing and that PPI or vonoprazan treatment for ESD-induced ulcers can be administrated at the standard dose irrespective of CYP2C19 genotype.

The endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early-stage gastric cancer is first-line therapy in Japan, because of en bloc resection and a lower local recurrence rate of gastric cancer. However, bleeding from ESD-induced ulcer is a major complication of ESD treatment. When ESD is performed for gastric cancer, PPIs or vonoprazan are used to treat ESD-induced ulcers in Japan. It remains unclear whether vonoprazan with more potent and sustained acid inhibition than PPIs, H. pylori infection and characteristics of gastric mucosa (e.g., inflammation and atrophy) are associated with improved ulcer healing speed and prevention of post-ESD bleeding. Rapid healing of ESD-induced ulcers is key to the prevention of delayed bleeding.

Of many possible factors related to ESD-induced ulcer healing, such as location of the tumor, submucosal fibrosis, initial ulcer size, diabetes, coagulation abnormality, electrocoagulation during ESD, and method of gastric acid suppression, it is unclear whether above parameters actually affect the healing of ESD-induced ulcers and the incidence of gastrointestinal bleeding after ESD treatment. Especially, there was no report investigated with the healing speed of ulcer after ESD and characteristics of gastric mucosa (e.g., inflammation and atrophy).

The main objective was to clarify factors that might be associated with healing of post-ESD ulcers and bleeding, including H. pylori status, profile of the gastric tumor, kinds of acid inhibitory drugs, and severity of gastritis including of gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia.

We retrospectively enrolled 132 patients with gastric tumors scheduled for ESD, irrespective to H. pylori infection. Following ESD, patients were treated with daily lansoprazole 30 mg or vonoprazan 20 mg for 8 wk. Ulcer size was endoscopically measured on the day after ESD and at 4 and 8 wk. The gastric mucosa was endoscopically graded according to the Kyoto gastritis scoring system. We assessed the number of patients with and without a 90% reduction in ulcer area at 4 wk post-ESD and scar formation at 8 wk, and looked for risk factors for slower healing.

After ESD, mean healing rates of ESD-related ulcer were 90.4% ± 0.8% at 4 wk and 99.8% ± 0.1% at 8 wk. The reduction rate was associated with the Kyoto grade of gastric mucosal atrophy at 4 wk and ESD-induced ulcers with ≥ 90% healing at 4 wk were associated with absence of atrophy, depth of gastric tumor, and procedure time. In the univariate analysis to identify possible factors related to achievement of 90% healing at 4 wk, healing was associated with gastric atrophy, procedure time and initial ESD-induced ulcer size. In the multivariate analysis, the factor associated with 90% healing at 4 wk was gastric mucosal atrophy (OR = 5.678, 95%CI: 1.190-27.085, P = 0.029).

The healing speed of ESD-induced ulcers was affected by the severity of gastric atrophy, but not by H. pylori status, kinds of acid inhibitory drugs, or CYP2C19 genotype. Patients with severe gastric atrophy accompanied by intestinal metaplasia should be considered as likely candidates for ESD-related complication, due to delayed ulcer healing. Therefore, H. pylori eradication therapy is required to perform at younger age before progression of gastric mucosal atrophy to prevent development of H. pylori-related diseases and bleeding from ESD-induced ulcer.

Eradication of H. pylori can be carried out at any time in terms of ulcer healing and that PPI or vonoprazan treatment for ESD-induced ulcers can be administrated at the standard dose irrespective of CYP2C19 genotype. However, because this is a preliminary small study, further study is required to plan whether the healing speed of ESD-induced ulcers was affected by the severity of gastric atrophy in prospective multicenter study. In addition, we will clarify the potential mechanism about association with the healing of ESD-induced ulcer and severity of gastric atrophy as further study.

| 1. | Uedo N, Iishi H, Tatsuta M, Ishihara R, Higashino K, Takeuchi Y, Imanaka K, Yamada T, Yamamoto S, Yamamoto S. Longterm outcomes after endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Tanabe S, Ishido K, Higuchi K, Sasaki T, Katada C, Azuma M, Naruke A, Kim M, Koizumi W. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a retrospective comparison with conventional endoscopic resection in a single center. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:130-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ono H, Yao K, Fujishiro M, Oda I, Nimura S, Yahagi N, Iishi H, Oka M, Ajioka Y, Ichinose M. Guidelines for endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer. Dig Endosc. 2016;28:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Higashiyama M, Oka S, Tanaka S, Sanomura Y, Imagawa H, Shishido T, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Risk factors for bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric epithelial neoplasm. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:290-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kagawa T, Iwamuro M, Ishikawa S, Ishida M, Kuraoka S, Sasaki K, Sakakihara I, Izumikawa K, Yamamoto K, Takahashi S. Vonoprazan prevents bleeding from endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced gastric ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:583-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Takizawa K, Oda I, Gotoda T, Yokoi C, Matsuda T, Saito Y, Saito D, Ono H. Routine coagulation of visible vessels may prevent delayed bleeding after endoscopic submucosal dissection--an analysis of risk factors. Endoscopy. 2008;40:179-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yang Z, Wu Q, Liu Z, Wu K, Fan D. Proton pump inhibitors versus histamine-2-receptor antagonists for the management of iatrogenic gastric ulcer after endoscopic mucosal resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Digestion. 2011;84:315-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shirai N, Furuta T, Xiao F, Kajimura M, Hanai H, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T. Comparison of lansoprazole and famotidine for gastric acid inhibition during the daytime and night-time in different CYP2C19 genotype groups. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:837-846. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Sugimoto M, Furuta T, Shirai N, Kajimura M, Hishida A, Sakurai M, Ohashi K, Ishizaki T. Different dosage regimens of rabeprazole for nocturnal gastric acid inhibition in relation to cytochrome P450 2C19 genotype status. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:290-301. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ashida K, Sakurai Y, Hori T, Kudou K, Nishimura A, Hiramatsu N, Umegaki E, Iwakiri K. Randomised clinical trial: vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, vs. lansoprazole for the healing of erosive oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:240-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Sakurai Y, Mori Y, Okamoto H, Nishimura A, Komura E, Araki T, Shiramoto M. Acid-inhibitory effects of vonoprazan 20 mg compared with esomeprazole 20 mg or rabeprazole 10 mg in healthy adult male subjects--a randomised open-label cross-over study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:719-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kagami T, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Uotani T, Yamade M, Sugimoto M, Hamaya Y, Iwaizumi M, Osawa S, Sugimoto K. Potent acid inhibition by vonoprazan in comparison with esomeprazole, with reference to CYP2C19 genotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1048-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Andersson K, Carlsson E. Potassium-competitive acid blockade: a new therapeutic strategy in acid-related diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:294-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Tsuchiya I, Kato Y, Tanida E, Masui Y, Kato S, Nakajima A, Izumi M. Effect of vonoprazan on the treatment of artificial gastric ulcers after endoscopic submucosal dissection: Prospective randomized controlled trial. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:576-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Yoshizawa Y, Sugimoto M, Sato Y, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Kagami T, Hosoda Y, Kimata M, Tamura S, Kobayashi Y. Factors associated with healing of artificial ulcer after endoscopic submucosal dissection with reference to Helicobacter pylori infection, CYP2C19 genotype, and tumor location: Multicenter randomized trial. Digest Endosc. 2016;28:162-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Horikawa Y, Mimori N, Mizutamari H, Kato Y, Shimazu K, Sawaguchi M, Tawaraya S, Igarashi K, Okubo S. Proper muscle layer damage affects ulcer healing after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2015;27:747-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Oh TH, Jung HY, Choi KD, Lee GH, Song HJ, Choi KS, Chung JW, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK. Degree of healing and healing-associated factors of endoscopic submucosal dissection-induced ulcers after pantoprazole therapy for 4 weeks. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1494-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lim JH, Kim SG, Choi J, Im JP, Kim JS, Jung HC. Risk factors of delayed ulcer healing after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:3666-3673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maruoka D, Arai M, Kasamatsu S, Ishigami H, Taida T, Okimoto K, Saito K, Matsumura T, Nakagawa T, Katsuno T. Vonoprazan is superior to proton pump inhibitors in healing artificial ulcers of the stomach post-endoscopic submucosal dissection: A propensity score-matching analysis. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Labenz J, Börsch G. Evidence for the essential role of Helicobacter pylori in gastric ulcer disease. Gut. 1994;35:19-22. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Satoh K, Yoshino J, Akamatsu T, Itoh T, Kato M, Kamada T, Takagi A, Chiba T, Nomura S, Mizokami Y. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:177-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim SG, Song HJ, Choi IJ, Cho WY, Lee JH, Keum B, Lee YC, Kim JG, Park SK, Park BJ. Helicobacter pylori eradication on iatrogenic ulcer by endoscopic resection of gastric tumour: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled multi-centre trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kakushima N, Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Kodashima S, Nakamura M, Omata M. Helicobacter pylori status and the extent of gastric atrophy do not affect ulcer healing after endoscopic submucosal dissection. J Gastroen Hepatol. 2006;21:1586-1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fujiwara S, Morita Y, Toyonaga T, Kawakami F, Itoh T, Yoshida M, Kutsumi H, Azuma T. A randomized controlled trial of rebamipide plus rabeprazole for the healing of artificial ulcers after endoscopic submucosal dissection. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:595-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sugimoto M, Ban H, Ichikawa H, Sahara S, Otsuka T, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Furuta T, Andoh A. Efficacy of the Kyoto Classification of Gastritis in Identifying Patients at High Risk for Gastric Cancer. Intern Med. 2017;56:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Asaka M, Sugiyama T, Nobuta A, Kato M, Takeda H, Graham DY. Atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia in Japan: results of a large multicenter study. Helicobacter. 2001;6:294-299. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Chen LW, Chang LC, Hua CC, Hsieh BJ, Chen SW, Chien RN. Analyzing the influence of gastric intestinal metaplasia on gastric ulcer healing in Helicobacter pylori-infected patients without atrophic gastritis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Howden CW, Hunt RH. The relationship between suppression of acidity and gastric ulcer healing rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1990;4:25-33. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Takeuchi K, Ueki S, Okabe S. Importance of gastric motility in the pathogenesis of indomethacin-induced gastric lesions in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1986;31:1114-1122. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Akimoto M, Hashimoto H, Shigemoto M, Maeda A, Yamashita K. Effects of antisecretory agents on angiogenesis during healing of gastric ulcers. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tsuchida T, Tsukamoto Y, Segawa K, Goto H, Hase S. Effects of cimetidine and omeprazole on angiogenesis in granulation tissue of acetic acid-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Digestion. 1990;47:8-14. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Szabo S, Folkman J, Vattay P, Morales RE, Pinkus GS, Kato K. Accelerated healing of duodenal ulcers by oral administration of a mutein of basic fibroblast growth factor in rats. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1106-1111. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Tarnawski A, Stachura J, Durbin T, Sarfeh IJ, Gergely H. Increased expression of epidermal growth factor receptor during gastric ulcer healing in rats. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:695-698. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Konturek SJ. Role of growth factors in gastroduodenal protection and healing of peptic ulcers. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1990;19:41-65. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Shigeta J, Takahashi S, Okabe S. Role of cyclooxygenase-2 in the healing of gastric ulcers in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:1383-1390. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Scott DR, Munson KB, Marcus EA, Lambrecht NW, Sachs G. The binding selectivity of vonoprazan (TAK-438) to the gastric H+, K+ -ATPase. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:1315-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hori Y, Imanishi A, Matsukawa J, Tsukimi Y, Nishida H, Arikawa Y, Hirase K, Kajino M, Inatomi N. 1-[5-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1-(pyridin-3-ylsulfonyl)-1H-pyrrol-3-yl]-N-methylmethanamine monofumarate (TAK-438), a novel and potent potassium-competitive acid blocker for the treatment of acid-related diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335:231-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Sugimoto M, Ban H, Hira D, Kamiya T, Otsuka T, Inatomi O, Bamba S, Terada T, Andoh A. Letter: CYP3A4/5 genotype status and outcome of vonoprazan-containing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1009-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yu C, Mei XT, Zheng YP, Xu DH. Gastroprotective effect of taurine zinc solid dispersions against absolute ethanol-induced gastric lesions is mediated by enhancement of antioxidant activity and endogenous PGE2 production and attenuation of NO production. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;740:329-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Owu DU, Obembe AO, Nwokocha CR, Edoho IE, Osim EE. Gastric ulceration in diabetes mellitus: protective role of vitamin C. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2012;2012:362805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Bugaj AM, Dinc T, Li Y, Sun LM S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D