修回日期: 2016-03-23

接受日期: 2016-03-28

在线出版日期: 2016-06-08

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)是一类反复发作的肠道慢性非特异性疾病, 其发病机制迄今未明, 越多的证据表明精神心理因素与IBD的进展及复发有关, 心理治疗可能是IBD传统疗法的重要补充. 本文就近年来IBD相关精神心理因素及治疗干预方式的研究进展进行简要综述, 提示临床医生加强识别IBD伴随的精神心理障碍, 重视精神心理治疗.

核心提示: 有相当一部分炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)患者合并有焦虑、抑郁等心理障碍, 心理治疗不但可以缓解精神症状, 同时对肠道和躯体症状兼具改善效果, 可预防过度医疗和IBD药物不必要的升级.

引文著录: 范一宏, 王诗怡. 治疗的艺术: 重视炎症性肠病患者的心理健康. 世界华人消化杂志 2016; 24(16): 2445-2453

Revised: March 23, 2016

Accepted: March 28, 2016

Published online: June 8, 2016

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, recurrent and idiopathic intestinal disorder whose pathogenesis remains unclear. An increasing amount of evidence has shown that psychological factors are closely related to the progression and recurrence of IBD. Psychotherapy can be an important supplement therapy to traditional IBD treatment. In this article we will briefly review the advances in research of IBD-related psychological factors and the corresponding intervention approaches. Clinicians should strengthen their awareness of IBD-related psychological disorders and put emphasis on psychotherapy.

- Citation: Fan YH, Wang SY. Art of therapy: Focus on psychological health among patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016; 24(16): 2445-2453

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v24/i16/2445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v24.i16.2445

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)是一类反复发作的肠道慢性非特异性疾病, 包括溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)、克罗恩病(Crohn's disease, CD)和未定型肠炎. 其发病机制迄今未明, 可能与免疫、遗传、感染、精神因素等有关. 虽然精神心理因素在本病发病中的作用尚存争议, 但已有证据表明精神心理因素与IBD的进展及复发有关. 由于病情的反复性、致残性及不可预见性, 使IBD患者心理脆弱; 此外, 补充和替代医学的广泛运用及临床试验中安慰剂的阳性治疗结果[1], 都进一步强调了IBD患者心理治疗的需求, 心理治疗可能是IBD传统疗法的重要补充. 因此, 本文就IBD相关精神心理因素及治疗作一概述, 旨在进一步提高临床诊治效果.

IBD患者有着很多共同的心理特点[2], 包括: 强迫行为、神经质、依赖、焦虑、不恰当的激进或愤怒、完美主义. 但目前没有证据支持, 某一种人格特质可诱发IBD的假说[3]. IBD症状的出现和加重可能与患者的精神心理因素有关, 但精神心理因素也可以是本病反复发作的继发表现[4], 两者可能互为因果.

流行病学调查显示[5], 在缓解期约有35%合并有抑郁或焦虑状态, 而当疾病活动时, 则会有60%的患者合并有抑郁, 而高达80%的患者存在焦虑状态(在美国正常人群的普查中, 抑郁和焦虑的发生率约为7%和18%), 且IBD抑郁发生率随病程延长而升高[6]. 在另一项包含1663例IBD患者的研究中, 分别约有11%和41%的患者存在抑郁和焦虑, 影响心理状态的相关因素主要为疾病的活动和社会经济能力的丧失[7]. 其中抑郁相关因素包括年龄(年轻)、疾病复发、残疾、失业状态、丧失经济社会能力; 而焦虑相关因素有疾病严重、治疗依从性差、致残、失业状态、丧失社会经济能力等. 另一项回顾性队列研究[6]显示, 女性(HR = 1.3, 95%CI: 1.1-1.7)、疾病进展(HR = 1.4, 95%CI: 1.02-1.9)和病情活动(HR = 1.5, 95%CI: 1.1-2.0)是抑郁症的独立预测因子. 所以, 相对于疾病分型, 疾病活动度才是影响心理健康结果的关键因素, 活动期IBD患者应积极评估焦虑和抑郁水平并给予适当干预[8,9]. 另有研究[10]发现, 无论疾病缓解与否, 疲乏感会随着病程的延长而增加, 其中情感抑郁、幸福感以及睡眠质量与疲乏感独立相关.

而关于情绪对IBD的影响, 大部分研究认为压力或抑郁会使IBD恶化[11], 更有研究发现重度抑郁可影响英夫利昔治疗CD的近期(诱导缓解)及远期疗效[12]. 而IBD患者的焦虑、抑郁情绪亦是影响健康相关生活质量(health-related quality of life, HRQOL)的独立因素, 并均与HRQOL呈负相关[13]. 持续处于焦虑、抑郁状态, 可能会加重患者的肠道症状, 减低疼痛的阈值, 从生理领域影响患者的健康相关生存质量; 同时焦虑、抑郁以及孤独感、情绪多变等情绪问题又会使患者不能正常地完成生活、工作和学习, 并同时会与亲戚、朋友逐渐疏远, 社交活动减少, 从社会领域方面影响患者的生存质量. 心理因素与受损的HRQOL对IBD病程可能产生不良影响, 而心理健康的IBD患者可以长期处于缓解状态[14].

IBD患者发生情绪障碍的病理生理学机制是多因素的, 结合大量文献分析, 精神心理因素可能通过改变脑-肠轴功能、增加内脏敏感性、促炎细胞因子等途径导致情绪障碍的发生.

研究表明, 心理-神经内分泌免疫调节通过脑-肠轴在IBD发病中起着关键作用, 抑郁和应激可能是由IBD本身导致, 但也有可能在发病过程起到激发或者放大的作用. IBD患者自主神经系统、中枢神经系统、应激系统(下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴)、消化道促肾上腺皮质激素释放因子(corticotropin-releasing factor, CRF)系统和肠道反应(包括肠屏障、肠微生物和肠道的免疫反应)功能均存在不同程度的失调, 并且与IBD活动密切相关[15]. 动物模型表明, 处于应激状态时, CRF可直接作用于脑致胃肠道运动、分泌、肠道通透性及局部炎症反应发生变化[16], 并与结肠炎的发生与复发相关[17]. 所以, 传出迷走神经的胆碱能抗炎通路, 通过TNF效应, 或将成为IBD的药物、营养或神经刺激的治疗靶点.

内脏高敏感亦参与了IBD相关性情绪障碍的发生[18]. 约有70%以上的IBD患者会出现腹痛症状, 慢性疼痛与抑郁症之间的联系, 类似于脑-肠轴, 是双相的. 抑郁症本身可表现为慢性躯体疼痛, 而对于IBD患者来说, 疼痛亦是抑郁症发生的独立危险因素[19]. 对于慢性炎症性疾病, 如IBD、类风湿性关节炎, 可对感觉传入神经形成持续性的增敏作用[18], 导致中枢神经疼痛处理过程发生改变, 继而导致下游情绪及认知过程的变化.

值得一提的是, 近年来有越来越多的研究者聚焦于炎症与压力的关系, 目前认为促炎细胞因子为引起抑郁症最为关键的因素, 可引起大脑结构和功能的改变, 从而引发情绪障碍[20,21]. 将两者联系起来的证据主要基于以下3个方面: (1)约有三分之一重度抑郁症患者表现为C反应蛋白、肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor α, TNF-α)、白介素(interleukin, IL)-6等外周血炎症指标的升高, 即使是在不合并有躯体疾病的患者[22,23]; (2)相比炎症指标正常的IBD患者, 伴有高水平急性相反应物者具有更高的抑郁症发生率. 另有Meta分析显示, 使用选择性五羟色胺再摄取抑制剂(selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, SSRI)治疗可使IL-1b和IL-6水平下降的同时改善抑郁症状[24]; (3)采用细胞因子(如干扰素α)治疗的患者具有更高罹患重度抑郁症的风险[25]. 可能的机制包括促炎因子对单胺类神经递质浓度直接的影响、下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴调节异常、小胶质细胞激活、神经重塑功能受损以及大脑结构及功能的改变[26].

IBD的药物治疗亦会引发情绪障碍, 有研究表明, 约有四分之一接受糖皮质激素治疗的患者有精神方面的不良反应[27], 约有10%服用强的松剂量超过20 mg/d的患者3 mo内因躁狂症或抑郁症而住院治疗. 在研究中, 精神症状为仅次于"满月脸"的不良反应, 其发生率与剂量呈正相关. 随着生物制剂等激素替代药物的广泛使用, 因激素引起IBD患者精神症状的发生率已日趋减少, 但仍应引起足够的重视.

约有20%的IBD患者需要心理治疗[28], 其方法可分为两大类, 即药物疗法和心理疗法.

目前认为SSRI(如西酞普兰、氟西汀、舍曲林)及五羟色胺去甲肾上腺素再摄取抑制剂(serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, SNRI), 如文拉法辛对于治疗伴有焦虑及抑郁的IBD患者均是安全及有效的[29], 可作为一线推荐药物. 此外, SSRI/SNRI在控制情绪症状的同时还可减少疼痛, 肠易激及排便急迫感, 从而改善生活质量[30]. 一项回顾性病例对照研究[31]显示IBD患者在接受抗抑郁药物治疗1年后复发率减少, 这或许可以解释那些良好心理状态的患者具有更少的功能性胃肠道症状. 此外, 在动物模型中抗抑郁药物已被证明可以改善可见的胃肠道炎症[32,33], 由此推断抗抑郁药在协助心理健康的同时也可能直接减少肠道炎症. 最近的一项调查显示, 约有80%的胃肠道专家会将抗抑郁药物作为辅助治疗, 特别是伴有疼痛及睡眠障碍的患者. 值得注意的是, 精神病药物的临床疗效一般需2-4 wk才会显现, 不良反应不在少数并且有可能是不确定的(如体重增加和性功能障碍), 终止治疗通常发生在第1周或第1个月, 应及时调整治疗药物以确保最佳的疗效及最小的不良反应.

心理疗法可分为以下四个方面: 压力管理、心理动力学疗法、认知行为疗法和催眠[34], 下面将分别阐述.

3.2.1 压力管理: 压力管理也称压力干预, 是指采取一些方法来增强个体应对压力情境和/或事件, 以及由此引起的负性情绪的能力, 并针对由于压力而导致的个人身心不适的症状进行处理[34]. 由于压力可以影响症状, 而压力是普遍存在的, 故调节压力可能对IBD症状产生显著影响. 压力管理被证明在改善IBD患者症状方面是有效的[35,36], 表现为腹痛、腹胀、便秘等症状的减少. 有报道称[37], 持续6 wk, 75 min/wk的放松训练课程可有效改善IBD患者的腹痛频率和强度, 并可减少抗炎药物的使用. RCT研究[38]显示压力管理能提高UC患者生活质量, 但并不改善疾病的病程以及减少疾病的复发率. 最近的指南中提出压力管理或可改善IBD相关性疲劳, 然而目前证据尚不充分[39].

3.2.2 心理动力学疗法: 心理动力学疗法又称为精神分析疗法, 他是建立在弗洛伊德所创立的精神分析理论基础上的治疗方法. 该理论认为, 很多疾病都与人的潜意识中的矛盾冲突有关, 如果把压抑在潜意识中的矛盾冲突、心理创伤和焦虑体验用内省的方法挖掘出来, 使之成为意识的东西并加以认知和疏导, 就达到了治疗目的. 整个治疗过程即是反复交谈、解释、修通, 使患者对其症状的真正含义达到领悟, 学会面对现实, 以更成熟有效的方式处理冲突而避免引发躯体的一系列症状.

研究[40]发现心理动力学治疗并不能改善患者的生活质量及焦虑和抑郁的程度, 而仅仅表现为适应性应对方式的减少. 德国的一个研究团队得出相似的结论[41,42], 指出心理动力学疗法仅能轻微地减少手术率及疾病的活动, 未能改善患者的社会心理学状态以及疾病的进程, 且这一微小的差异可能与样本的基线偏差相关[41]. 而进一步的亚组分析发现, 心理动力学疗法并非完全无效, 那些医疗资源高度使用者的住院天数及病假日显著减少[43]. Oxelmark等[44]描述一个由9个课程组成的干预系统, 采用患者教育讲座和由医务社会工作者/心理学家集体心理治疗两种方式交替进行, 虽然仅有短病程的IBD患者表现为生活方式的改善, 但该心理干预方式最大的价值体现在当个体处于一个患者群体中时可以从他人身上获得更多的力量及关于疾病的认知.

3.2.3 认知行为疗法: 认知行为治疗(cognitive-behavioral therapy, CBT)是认知与行为相结合的疗法, 其主要治疗策略是分析患者的信念与正常人的差距, 指出其不合理性, 督促患者改变想法和态度, 以理性代替非理性的观念, 在不断的教育中建立健康的认知模式, 同时改变不良的行为. Schwarz等[45]对UC和CD患者进行多重行为治疗干预研究, 干预包括IBD教育及认知应对策略应用, 未发现症状的改善, 但干预组主观感觉疾病压力以及抑郁焦虑的状态有明显减轻. 在另一项回顾性病例分析研究中[46], 研究者发现使用行为认知治疗和焦点解决短期治疗双重心理干预手段不仅可以提高患者的HRQOL, 还能降低疾病的复发率、减少类固醇和其他药物的使用量以及门诊的就诊人次. 从总体角度来说, CBT更表现为对患者心理状态而非疾病的改善. Mussell等[47]研究发现CBT可减少UC患者疾病相关的担忧和顾虑, 在女性人群中抑郁状态可以得到稳定的降低. 此外, 还有研究显示CBT可改善患者的生活质量, 特别是对于那些伴有IBS样症状的患者[48]以及UC患者[38].

3.2.4 催眠: 催眠疗法能使患者进入放松状态, 通过中枢机制改变肠道功能状态从而改善症状. 一般认为, 催眠疗法对于提高患者的生活质量是有效的[49], 亦有学者研究发现其还可减轻症状的严重程度[50]及降低疾病的活动度[51], 显著延长UC患者临床缓解时间[52]. 在另一项UC患者的研究[53]中, 催眠疗法可减少全身和直肠黏膜炎症反应, 降低黏膜血流量、氧化应激以及TNF-α、IL-6、IL-13水平. 近年来, 肠道定向催眠疗法(gut-directed hypnotherapy, GHT)已被成功应用于治疗功能性胃肠病, 最近, 有系列案例报道[54]显示其亦可改善IBD患者的肠道症状以及生活质量, 更有前瞻性研究[55]进一步表明GHT似乎有免疫调节作用, 可明显延长UC患者的临床缓解期. 与CBT相比, 催眠疗法似乎对于疾病症状的改善更为明显, 适用于心理状态尚可而IBS样症状较为明显的患者[34].

IBD是慢性病, 影响人群多是青少年, 患者常因为突出的肠道症状不能正常的学习, 来自团体的社会支持较正常的人群为少, 同时需要更多的家庭照护支持. 在此背景下, 患者更容易产生自卑和自我歧视. 此外, 儿童及青少年的IBD患者病变往往更广泛, 预后也更差[56]. 基于青少年IBD心理治疗的特殊性, 故本节单独阐述.

一旦确诊为IBD, 应当对患儿的心理健康问题进行筛查, 这不仅影响到疾病的治疗, 还关乎其在学校的学习和生活质量[57]. 对患者进行社会心理评估可从抑郁筛查开始, 推荐应用PHQ-9量表进行评估, 操作简单且无需心理医生辅助[58]. 也可应用儿童抑郁量表(CDI, 7-17岁)、Beck抑郁自评量表(BDI, 18岁及以上)或MESSAGE量表[59].

系统评价显示, 青少年人群更可能从心理治疗中获益[60], 在报道的文献中, 干预多数采用CBT方式, 旨在提高患者的疾病应对策略及进行认知重构. 通常, 父母也需同时接受心理学教育. Szigethy等[61]将初级和次级的控制强化训练(primary and secondary control enhancement therapy-physical illness, PASCET-PI)应用于青少年IBD患者, 该干预方式包括对患儿疾病的叙述、问题解决策略、放松技巧和自我催眠等, 旨在修正患者的负面认知. 结果表明PASCET-PI可有效减少患者抑郁症状, 同时提升健康感知, 降低无助感及增强社交能力. 而对于伴有中-重度炎症的青少年, 无论疾病活动与否, 相比于支持治疗CBT在统计学及临床上对躯体抑郁症状和潜在炎症有更显著的效果, 因此在该组人群中应优先考虑[62].

伴随着越来越多的证据涌现, 已初步显示心理治疗对IBD的病程起到积极作用, 在未来需要通过前瞻性对照试验得出更多的数据, 以明确心理治疗对IBD的作用. 目前中国IBD患者心理治疗相关研究较少: 国人对心理治疗的反应是否与国外一致? 哪一类IBD患者最有可能从心理干预中获益? UC和CD患者在接受心理治疗时是否应该区别对待? 心理干预的最佳治疗时间? 这些问题均还有待进一步的研究来解决. 此外, 精神科药物, 包括抗抑郁剂的影响, 必须进一步评估; 药物治疗与心理治疗疗效的差异有待进一步比较. 而在基础研究方面, 脑-肠轴具体作用机制及潜在的治疗靶点均值得我们深入探索.

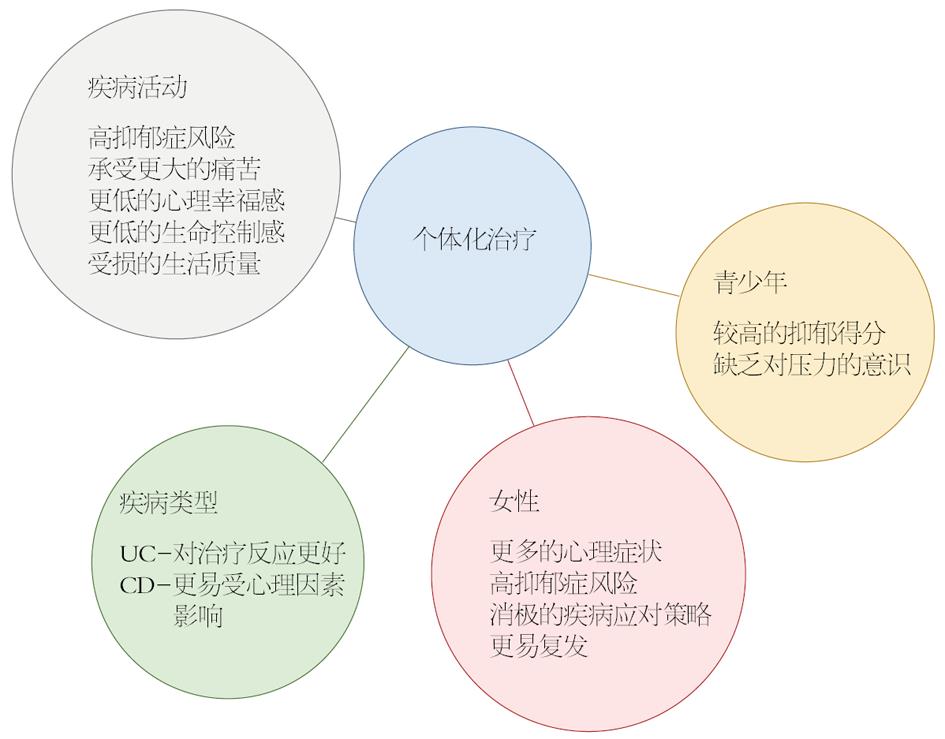

心理治疗不但可以减轻IBD患者焦虑、抑郁等精神症状, 同时对肠道和躯体症状兼具改善效果, 预防过度医疗和IBD药物不必要的升级, 是IBD传统疗法的重要补充, 具有相当大的发展前景. 采用个体化治疗是非常有必要的[63]: 处于疾病活动期的患者往往有着更低的心理幸福感及生活质量, 罹患抑郁症的风险增加; 与UC患者相比CD患者更易受心理因素影响; 女性通常采取消极的疾病应对策略, 更易发生抑郁症; 而青少年患者往往具有较高的抑郁得分, 并且缺乏对压力及心理问题的意识(图1).

从心理干预方案的选择上来说[34], 心理动力学疗法以及CBT, 似乎对于改善IBD相关焦虑和抑郁情绪更为有效. 相比之下, 催眠疗法似乎更有利于身体症状和生活质量的提升. 而压力管理更多的在于关注患者情绪的放松. 此外, 疾病的不同阶段应采用不同的治疗方式[64]. 在IBD尚未完全确诊或诊断初期, 进行疾病宣教或朋辈心理辅导更为合适; 而随着疾病的进展, 个体化使用压力管理、心理动力学疗法、CBT、催眠疗法或抗抑郁药物; 对于合并有严重抑郁或焦虑症的患者, 则应同时进行精神科的检查及治疗.

所以, 基于现今所提倡的生物-心理-社会医学模式, 对于IBD的诊治应当认识到疾病的生理和心理层面, 并提供一个以多学科协作团队为基础的平台使得医生与患者之间更好地交流[65], 这就是IBD治疗的"艺术", 这对于改善IBD患者症状、减少复发及改善生活质量均有着重要的临床意义.

流行病学调查显示, 在缓解期约有35%的炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)患者合并有抑郁或焦虑状态, 而当疾病活动时, 则会有60%的患者合并有抑郁, 而高达80%的患者存在焦虑状态. 不良的心理状态不仅会影响生活质量, 更有文献认为压力或抑郁会加重患者肠道症状, 使IBD复发率增加.

蒋小华, 副教授, 副主任医师, 同济大学附属东方医院胃肠外科; 沈卫东, 副主任医师, 东南大学医学院附属江阴医院消化内科

心理治疗是IBD传统疗法的重要补充, 不仅可减轻IBD患者焦虑、抑郁等精神症状, 同时对肠道和躯体症状兼具改善效果. 心理治疗主要包括药物治疗和心理疗法两大类, 而后者可采用压力管理、心理动力学疗法、认知行为疗法和催眠等多种方式.

IBD患者自主神经系统、中枢神经系统、应激系统(下丘脑-垂体-肾上腺轴)、消化道促肾上腺皮质激素释放因子(corticotropin-releasing factor, CRF)系统和肠道反应(包括肠屏障、肠微生物和肠道的免疫反应)功能均存在不同程度的失调, 并且与IBD活动密切相关, Bonaz等对此作了系统性的总结.

本文就近年来IBD相关精神心理因素及治疗干预方式的研究进展进行简要综述, 提示临床医生加强识别IBD伴随的精神心理障碍, 重视精神心理治疗.

本文旨在通过阐述精神心理因素与IBD的关系, 介绍目前常用的心理治疗方式, 提倡IBD生理和心理的综合治疗.

修通: 指心理咨询师通过反复诠释的过程, 让患者以往潜意识中受到压抑的内在冲突浮现在意识面层面, 使得患者能够对其心理困扰的原由获得充分的领悟.

本文就近年来IBD相关精神心理因素及治疗干预方式的研究进展进行综述, 指出IBD患者存在伴随的精神心理障碍的风险, 在临床工作中应重视并积极治疗. 论述准确, 条理清楚, 文章结构思路清晰, 对IBD相关的临床医生在临床工作有裨益.

| 1. | Mawdsley JE, Rampton DS. Psychological stress in IBD: new insights into pathogenic and therapeutic implications. Gut. 2005;54:1481-1491. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | McMahon AW, Schmitt P, Patterson JF, Rothman E. Personality differences between inflammatory bowel disease patients and their healthy siblings. Psychosom Med. 1973;35:91-103. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Häuser W, Moser G, Klose P, Mikocka-Walus A. Psychosocial issues in evidence-based guidelines on inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3663-3671. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Leone D, Menichetti J, Fiorino G, Vegni E. State of the art: psychotherapeutic interventions targeting the psychological factors involved in IBD. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:1020-1029. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Bannaga AS, Selinger CP. Inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety: links, risks, and challenges faced. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2015;8:111-117. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Panara AJ, Yarur AJ, Rieders B, Proksell S, Deshpande AR, Abreu MT, Sussman DA. The incidence and risk factors for developing depression after being diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease: a cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:802-810. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, Olympie A, Lesgourgues B, Colombel JF, Gendre JP. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086-2091. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Häuser W, Janke KH, Klump B, Hinz A. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: comparisons with chronic liver disease patients and the general population. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:621-632. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies Revisited: A Systematic Review of the Comorbidity of Depression and Anxiety with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:752-762. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Graff LA, Clara I, Walker JR, Lix L, Carr R, Miller N, Rogala L, Bernstein CN. Changes in fatigue over 2 years are associated with activity of inflammatory bowel disease and psychological factors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1140-1146. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Triantafillidis JK, Merikas E, Gikas A. Psychological factors and stress in inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:225-238. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Persoons P, Vermeire S, Demyttenaere K, Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, Pierik M, Hlavaty T, Van Assche G, Noman M. The impact of major depressive disorder on the short- and long-term outcome of Crohn's disease treatment with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:101-110. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, Tillinger W, Gangl A, Moser G. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:79-84. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Tabibian A, Tabibian JH, Beckman LJ, Raffals LL, Papadakis KA, Kane SV. Predictors of health-related quality of life and adherence in Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: implications for clinical management. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1366-1374. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Bonaz BL, Bernstein CN. Brain-gut interactions in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:36-49. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Taché Y, Perdue MH. Role of peripheral CRF signalling pathways in stress-related alterations of gut motility and mucosal function. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16 Suppl 1:137-142. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Gué M, Bonbonne C, Fioramonti J, Moré J, Del Rio-Lachèze C, Coméra C, Buéno L. Stress-induced enhancement of colitis in rats: CRF and arginine vasopressin are not involved. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G84-G91. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Srinath AI, Goyal A, Zimmerman LA, Newara MC, Kirshner MA, McCarthy FN, Keljo D, Binion D, Bousvaros A, DeMaso DR. Predictors of abdominal pain in depressed pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1329-1340. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Zimmerman LA, Srinath AI, Goyal A, Bousvaros A, Ducharme P, Szigethy E, Nurko S. The overlap of functional abdominal pain in pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:826-831. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Slavich GM, Irwin MR. From stress to inflammation and major depressive disorder: a social signal transduction theory of depression. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:774-815. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Horst S, Chao A, Rosen M, Nohl A, Duley C, Wagnon JH, Beaulieu DB, Taylor W, Gaines L, Schwartz DA. Treatment with immunosuppressive therapy may improve depressive symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:465-470. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, Lanctôt KL. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446-457. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:230-239. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Hannestad J, DellaGioia N, Bloch M. The effect of antidepressant medication treatment on serum levels of inflammatory cytokines: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:2452-2459. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Bonaccorso S, Puzella A, Marino V, Pasquini M, Biondi M, Artini M, Almerighi C, Levrero M, Egyed B, Bosmans E. Immunotherapy with interferon-alpha in patients affected by chronic hepatitis C induces an intercorrelated stimulation of the cytokine network and an increase in depressive and anxiety symptoms. Psychiatry Res. 2001;105:45-55. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Krishnadas R, Cavanagh J. Depression: an inflammatory illness? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:495-502. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Fardet L, Kassar A, Cabane J, Flahault A. Corticosteroid-induced adverse events in adults: frequency, screening and prevention. Drug Saf. 2007;30:861-881. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Miehsler W, Weichselberger M, Offerlbauer-Ernst A, Dejaco C, Reinisch W, Vogelsang H, Machold K, Stamm T, Gangl A, Moser G. Which patients with IBD need psychological interventions? A controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1273-1280. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Filipovic BR, Filipovic BF. Psychiatric comorbidity in the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:3552-3563. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Mikocka-Walus AA, Gordon AL, Stewart BJ, Andrews JM. A magic pill? A qualitative analysis of patients' views on the role of antidepressant therapy in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:93. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Goodhand JR, Greig FI, Koodun Y, McDermott A, Wahed M, Langmead L, Rampton DS. Do antidepressants influence the disease course in inflammatory bowel disease? A retrospective case-matched observational study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1232-1239. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Collins SM. Impaired parasympathetic function increases susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of depression. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2209-2218. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Ghia JE, Blennerhassett P, Deng Y, Verdu EF, Khan WI, Collins SM. Reactivation of inflammatory bowel disease in a mouse model of depression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2280-2288. e1-e4. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Knowles SR, Monshat K, Castle DJ. The efficacy and methodological challenges of psychotherapy for adults with inflammatory bowel disease: a review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2704-2715. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Smith GD, Watson R, Roger D, McRorie E, Hurst N, Luman W, Palmer KR. Impact of a nurse-led counselling service on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Adv Nurs. 2002;38:152-160. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | García-Vega E, Fernandez-Rodriguez C. A stress management programme for Crohn's disease. Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:367-383. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Shaw L, Ehrlich A. Relaxation training as a treatment for chronic pain caused by ulcerative colitis. Pain. 1987;29:287-293. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Boye B, Lundin KE, Jantschek G, Leganger S, Mokleby K, Tangen T, Jantschek I, Pripp AH, Wojniusz S, Dahlstroem A. INSPIRE study: does stress management improve the course of inflammatory bowel disease and disease-specific quality of life in distressed patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease? A randomized controlled trial. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1863-1873. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Kreijne JE, Lie MR, Vogelaar L, van der Woude CJ. Practical Guideline for Fatigue Management in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:105-111. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Maunder RG, Esplen MJ. Supportive-expressive group psychotherapy for persons with inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:622-626. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Keller W, Pritsch M, Von Wietersheim J, Scheib P, Osborn W, Balck F, Dilg R, Schmelz-Schumacher E, Doppl W, Jantschek G. Effect of psychotherapy and relaxation on the psychosocial and somatic course of Crohn's disease: main results of the German Prospective Multicenter Psychotherapy Treatment study on Crohn's Disease. J Psychosom Res. 2004;56:687-696. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Deter HC, Keller W, von Wietersheim J, Jantschek G, Duchmann R, Zeitz M. Psychological treatment may reduce the need for healthcare in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:745-752. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Deter HC, von Wietersheim J, Jantschek G, Burgdorf F, Blum B, Keller W. High-utilizing Crohn's disease patients under psychosomatic therapy. Biopsychosoc Med. 2008;2:18. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Oxelmark L, Magnusson A, Löfberg R, Hillerås P. Group-based intervention program in inflammatory bowel disease patients: effects on quality of life. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:182-190. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Schwarz SP, Blanchard EB. Evaluation of a psychological treatment for inflammatory bowel disease. Behav Res Ther. 1991;29:167-177. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Wahed M, Corser M, Goodhand JR, Rampton DS. Does psychological counseling alter the natural history of inflammatory bowel disease? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:664-669. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Mussell M, Böcker U, Nagel N, Olbrich R, Singer MV. Reducing psychological distress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease by cognitive-behavioural treatment: exploratory study of effectiveness. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:755-762. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Vogelaar L, Van't Spijker A, Vogelaar T, van Busschbach JJ, Visser MS, Kuipers EJ, van der Woude CJ. Solution focused therapy: a promising new tool in the management of fatigue in Crohn's disease patients psychological interventions for the management of fatigue in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:585-591. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Kwiatek MA, Palsson O, Taft TH, Martinovich Z, Barrett TA. The potential role of a self-management intervention for ulcerative colitis: a brief report from the ulcerative colitis hypnotherapy trial. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14:71-77. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Miller V, Whorwell PJ. Treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a role for hypnotherapy? Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2008;56:306-317. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Emami MH, Gholamrezaei A, Daneshgar H. Hypnotherapy as an adjuvant for the management of inflammatory bowel disease: a case report. Am J Clin Hypn. 2009;51:255-262. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Keefer L, Kiebles JL, Martinovich Z, Cohen E, Van Denburg A, Barrett TA. Behavioral interventions may prolong remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:145-150. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | Mawdsley JE, Jenkins DG, Macey MG, Langmead L, Rampton DS. The effect of hypnosis on systemic and rectal mucosal measures of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1460-1469. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Moser G. The role of hypnotherapy for the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;8:601-606. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | Keefer L, Taft TH, Kiebles JL, Martinovich Z, Barrett TA, Palsson OS. Gut-directed hypnotherapy significantly augments clinical remission in quiescent ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:761-771. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Turner D, Levine A, Escher JC, Griffiths AM, Russell RK, Dignass A, Dias JA, Bronsky J, Braegger CP, Cucchiara S. Management of pediatric ulcerative colitis: joint ECCO and ESPGHAN evidence-based consensus guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55:340-361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Singh H, Nugent Z, Brownell M, Targownik LE, Roos LL, Bernstein CN. Academic Performance among Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Population-Based Study. J Pediatr. 2015;166:1128-1133. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 59. | Mackner LM, Greenley RN, Szigethy E, Herzer M, Deer K, Hommel KA. Psychosocial issues in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:449-458. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 60. | Timmer A, Preiss JC, Motschall E, Rücker G, Jantschek G, Moser G. Psychological interventions for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD006913. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Szigethy E, Kenney E, Carpenter J, Hardy DM, Fairclough D, Bousvaros A, Keljo D, Weisz J, Beardslee WR, Noll R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease and subsyndromal depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46:1290-1298. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 62. | Szigethy E, Youk AO, Gonzalez-Heydrich J, Bujoreanu SI, Weisz J, Fairclough D, Ducharme P, Jones N, Lotrich F, Keljo D. Effect of 2 psychotherapies on depression and disease activity in pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1321-1328. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 63. | Wahed M, Rampton DS. Psychological Stress and related mood disorders, and their therapeutic implications in IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Monitor. 2013;13:143-153. |

| 64. | Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull D, Holtmann G, Andrews JM. An integrated model of care for inflammatory bowel disease sufferers in Australia: development and the effects of its implementation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1573-1581. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 65. | Van de star T, Banan A. Role of psychosocial factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease and associated psychotherapeutic approaches. A fresh perspective and review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 2015;2:1-13. [DOI] |

编辑: 于明茜 电编:闫晋利