Published online Apr 14, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i14.1949

Peer-review started: December 26, 2023

First decision: January 24, 2024

Revised: February 5, 2024

Accepted: March 25, 2024

Article in press: March 25, 2024

Published online: April 14, 2024

Processing time: 108 Days and 9.8 Hours

In Japan, liver biopsies were previously crucial in evaluating the severity of hepatitis caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV) and diagnosing HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, due to the development of effective antiviral treatments and advanced imaging, the necessity for biopsies has significantly decreased. This change has resulted in fewer chances for diagnosing liver disease, causing many general pathologists to feel less confident in making liver biopsy diagnoses. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the challenges and potential solutions related to liver biopsies in Japan. First, it highlights the importance of considering steatotic liver diseases as independent conditions that can coexist with other liver diseases due to their increasing prevalence. Second, it emphasizes the need to avoid hasty assumptions of HCC in nodular lesions, because clinically diagnosable HCCs are not targets for biopsy. Third, the importance of diagnosing hepatic immune-related adverse events caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors is increasing due to the anticipated widespread use of these drugs. In conclusion, pathologists should be attuned to the changing landscape of liver diseases and approach liver biopsies with care and attention to detail.

Core Tip: Over the past 30 years in Japan, liver biopsies for assessing hepatitis C virus (HCV) hepatitis and HCV-related liver cancer were common but declined due to advanced treatments and imaging. This shift decreased diagnostic opportunities and eroded general pathologists’ confidence in conducting liver biopsies. This editorial outlines key challenges: Understanding steatotic liver diseases as independent conditions, caution in diagnosing nodular lesions to prevent misinterpretation, and addressing hepatic injuries caused by immune checkpoint inhibitors. It stresses the need for pathologists to adapt to evolving liver disease landscapes and approach biopsies meticulously.

- Citation: Ikura Y, Okubo T, Sakai Y. Liver biopsy in the post-hepatitis C virus era in Japan. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(14): 1949-1957

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i14/1949.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i14.1949

I (Yoshihiro Ikura) started my career in pathology in Japan about 30 years ago, when abundant liver biopsies for interferon treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV)[1,2] were submitted to pathology laboratories, day after day (Figure 1). Those who do not know about those days may think that it must have been very tough, but it was rather easy because all we had to do was to evaluate the severity of hepatitis and diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

In 2014, oral direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) were introduced[3,4], resulting in a steady decline of liver biopsies in Japan (Figure 2). Pretherapeutic histologic examination is not required for DAA administration[5], and most HCC cases can be treated based solely on radiological findings[6]. Consequently, the necessity of pathologic assessment of liver specimens is decreasing. This is a favorable change for minimizing patients’ burden. However, opportunities for general pathologists to learn hepatic histopathology have decreased.

The changing landscape of liver diseases in Japan has caused many general pathologists to lack confidence in making liver biopsy diagnoses. This article categorizes the current issues surrounding liver biopsies in Japan and provides an overview of how to address them.

Liver biopsies from patients with steatotic liver diseases (SLDs; either metabolic dysfunction-associated or alcoholic) and positive for autoantibodies are frequently submitted to our pathology laboratory as consultation cases. Figure 3A and B shows an example of such a case, where steatosis and inflammatory injury are evident, but the portal area remains almost unaffected (Figure 3A). I informed the physician that the patient had steatohepatitis, which is characterized by hepatocyte ballooning and lipogranulomas (Figure 3B), there being no findings of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

Figure 3C-E provides a contrasting example. The liver biopsy of a diabetic patient shows inflammatory changes associated with steatosis, similar to the previous case (Figure 3C). Additionally, the portal area exhibits inflammation and fibrosis, and most importantly, inflammatory bile duct damage (Figure 3D) with a small granuloma formation (Figure 3E). These findings are typical of primary biliary cholangitis. The patient’s serological test confirmed a positivity for anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Complications of SLDs are apt to obscure the features of autoimmune liver diseases.

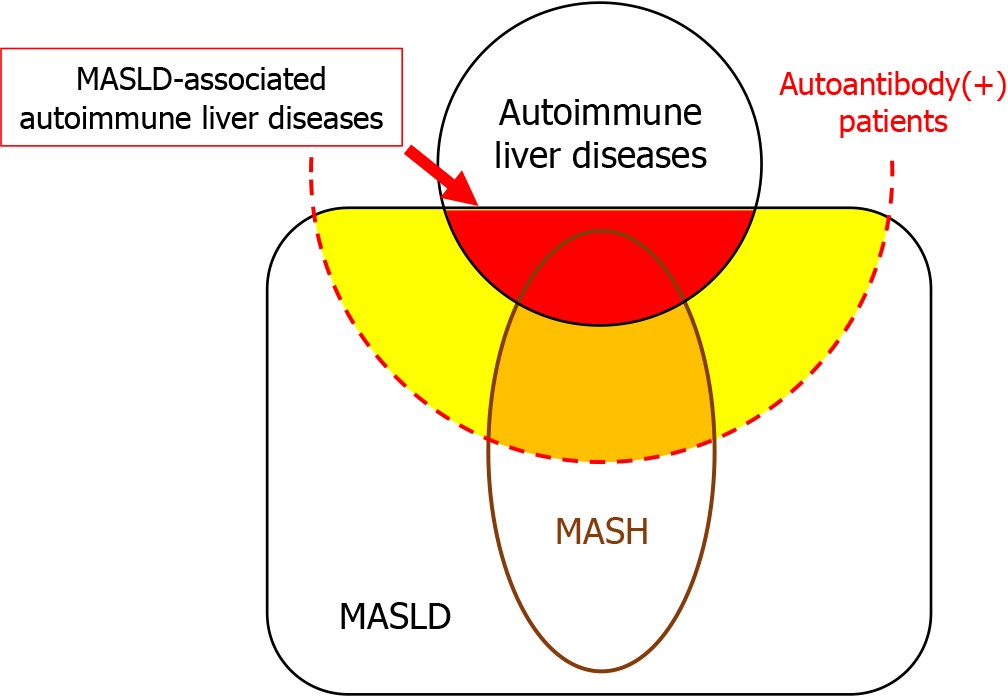

Currently, SLDs are estimated to affect 30% of the general adult population[7]. It should be noted that 30% of patients with autoimmune liver diseases, as well as those who are positive for autoantibodies but do not have autoimmune liver diseases, also have SLDs (Figure 4). Pathology reports should provide comments on whether SLDs are complicated by other liver diseases, rather than differentiating between them.

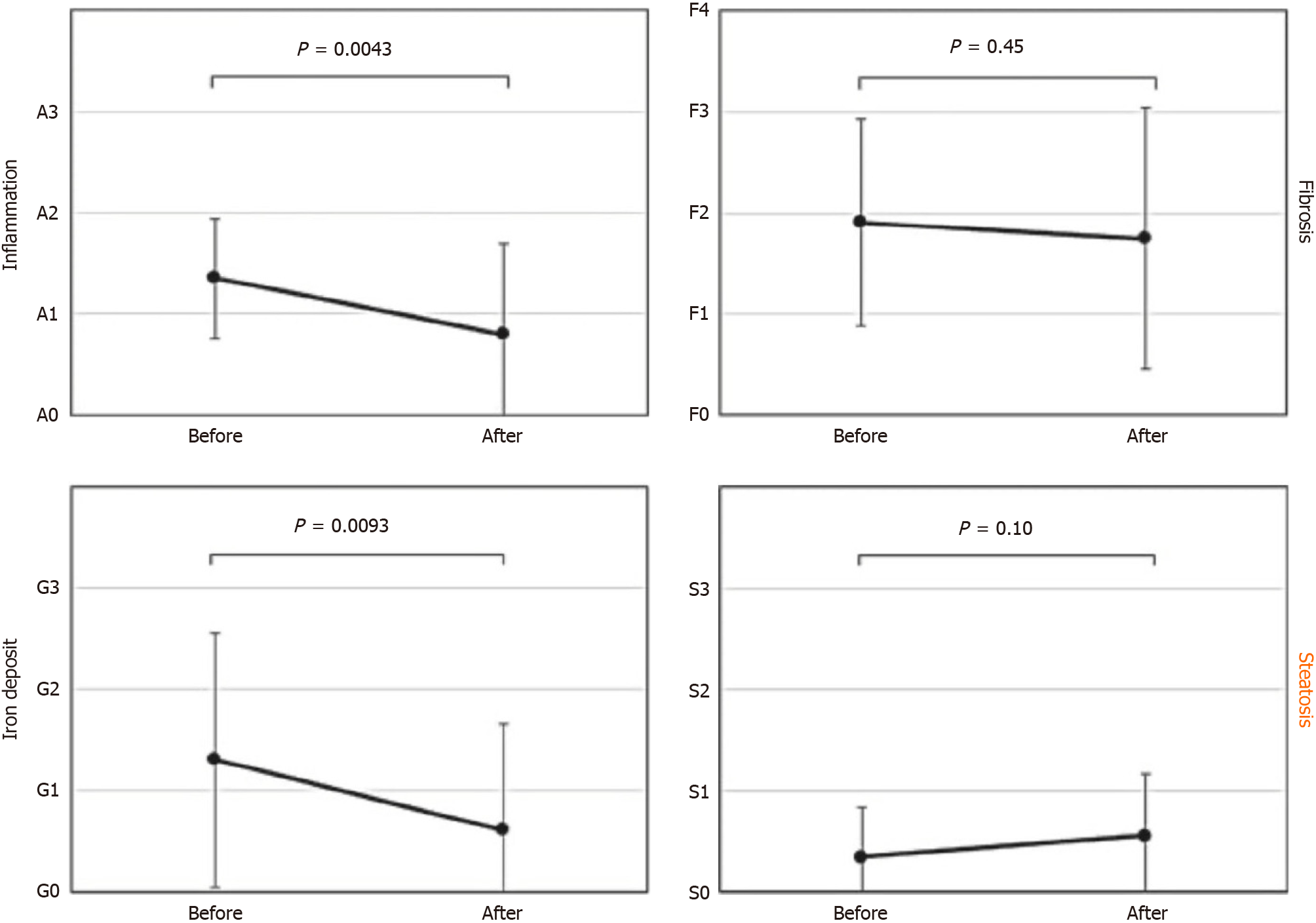

Figure 5 shows results of the comparative biopsy findings before and after HCV eradication with DAAs[8]. While inflammation, fibrosis and iron deposition have improved, steatosis appears to have worsened. This indicates that steatosis was an independent lesion, and not connected to HCV hepatitis. The data suggest that it is time to completely revise the conventional perspective of steatosis as a secondary change linked to various liver diseases.

The diagnosis of classical HCV-associated HCC was relatively easy because almost all cases had cirrhosis in the background and were observed as clearly demarcated atypical hepatocyte proliferation bordered by fibrous bundles (Figure 6). The histologic features of the current HCCs differ significantly from those of the classic HCCs. HCCs are increasingly developing in livers with only mild steatosis, without hepatitis or cirrhosis. Pathologists in Japan must abandon their previous understanding that HCC is usually associated with cirrhosis[9,10]. Diagnosing HCC has become increasingly challenging. Immunostaining, such as Glypican-3 and CD34, is recommended for cases where morphological diagnosis is difficult.

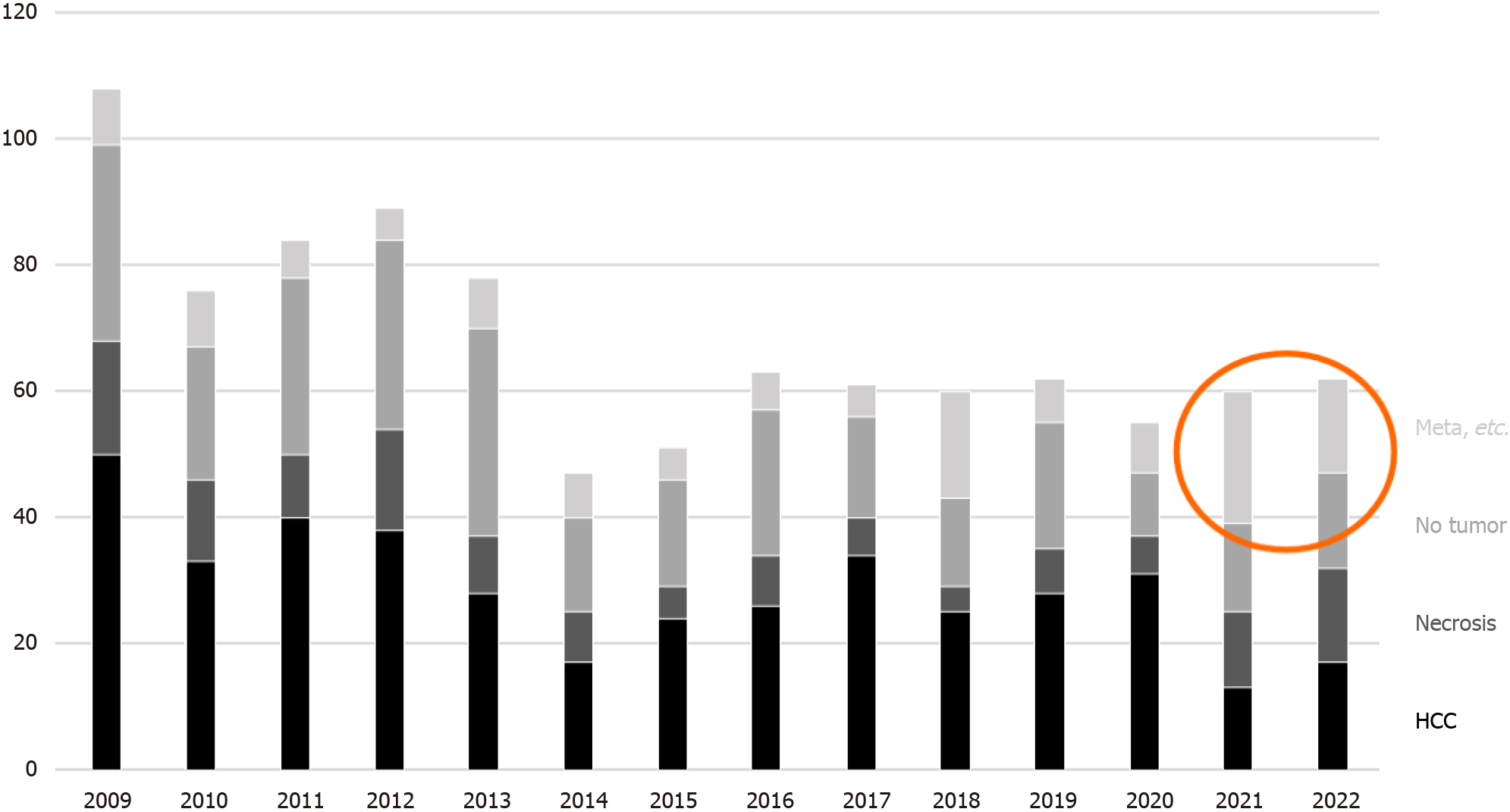

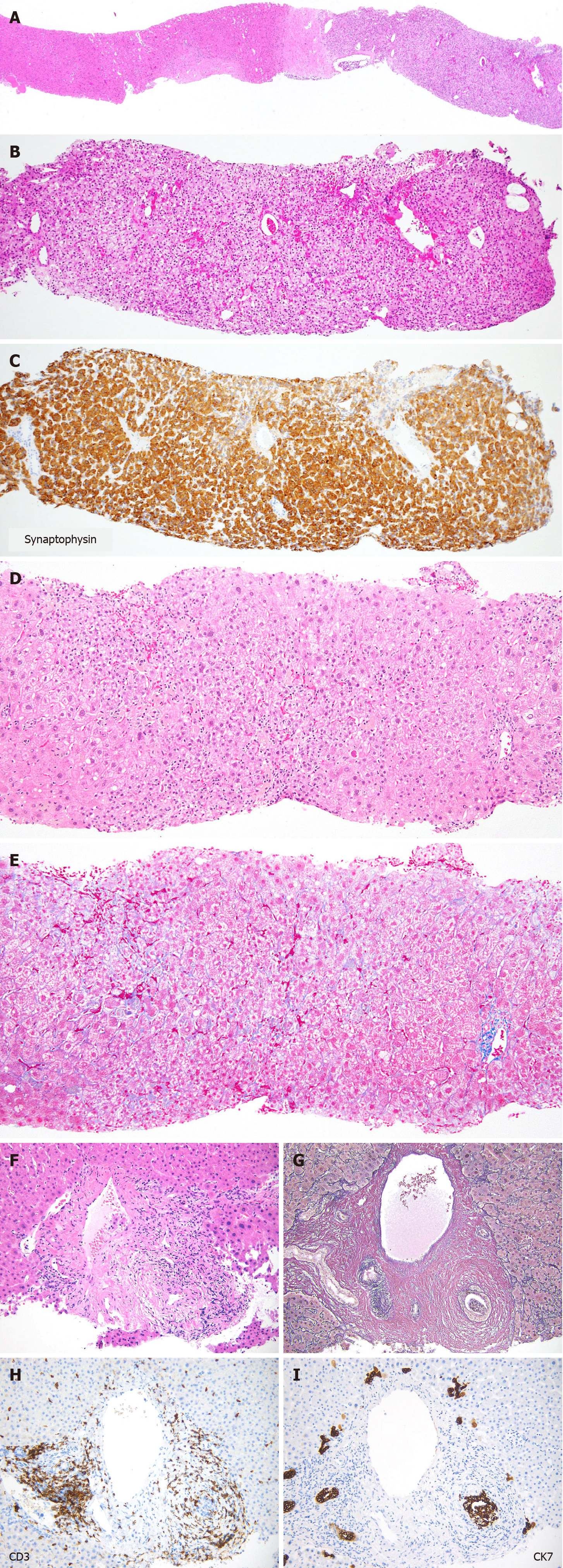

Among the biopsies for nodular lesions, the number of biopsies to diagnose HCC is decreasing. In addition to a certain percentage of tumor-free specimens, it is noteworthy that metastases and benign lesions have increased in recent years (Figure 7). Figure 8A-C shows a liver biopsy sent to our pathology laboratory as a consultation case, which originally had been diagnosed as HCC by biopsy a few years previously, then the tumor recurred repeatedly. The physician performed re-biopsy because of its unusual biological behavior inconsistent with HCC. No background cirrhosis was observed. The lesion consisted of cells with mild atypia and pale cytoplasm showing a cord-like arrangement. I couldn’t accept the diagnosis of recurrent HCC, so I ordered immunostaining, which was positive for synaptophysin, and replied that it was probably a metastasis of a neuroendocrine tumor.

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI), including immune checkpoint inhibitors-related adverse effects (irAE), will become an increasingly important problem, and may require more detailed histologic assessment[11,12].

Figure 8D and E shows a liver biopsy from a patient clinically suspected of AIH, due to positive antinuclear antibody and abnormally elevated serum IgG. The liver tissue shows mild fibrosis, and the main site of injury being centrolobular, indicating acute injury. There are no findings such as hepatocyte rosettes or cobblestone-like arrangement that strongly suggest AIH. I recommended that the possibility of drug-induced injury should be considered first in terms of frequency. The patient was later diagnosed with DILI, caused by one of the regular medications.

Figure 8F-I illustrates a case of bile duct injury that occurred three months after the initiation of nivolumab treatment for melanoma. Inflammatory cell infiltration and concentric fibrosis surround the interlobular bile ducts. The infiltrating cells were mostly CD3-positive T lymphocytes, with CD8-positive cells predominating over CD4-positive cells. CK7 staining clearly showed bile duct injury, which was ambiguous in the Hematoxylin & eosin slide. These pathologic changes were consistent with irAEs. After withdrawal of nivolumab, laboratory values returned to normal without the use of steroids.

The histologic diagnosis of a liver biopsy requires careful evaluation, taking into account a detailed history of drug use.

In the post-HCV era, the number of liver biopsies is decreasing, but their variation is increasing. Pathologic diagnosis of liver biopsies needs appreciation of the changing landscape of liver disease.

We thank Dr. Noriyo Yamashiki from Kansai Medical University for providing valuable comments on current clinical issues related to various liver diseases.

| 1. | Hoofnagle JH, Mullen KD, Jones DB, Rustgi V, Di Bisceglie A, Peters M, Waggoner JG, Park Y, Jones EA. Treatment of chronic non-A,non-B hepatitis with recombinant human alpha interferon. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1575-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 704] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kakumu S, Arao M, Yoshioka K, Ichimiya H, Murase K, Aoi T, Kusakabe A. Pilot study of recombinant human alpha-interferon for chronic non-A, non-B hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:40-45. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Poordad F. Big changes are coming in hepatitis C. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Omata M, Nishiguchi S, Ueno Y, Mochizuki H, Izumi N, Ikeda F, Toyoda H, Yokosuka O, Nirei K, Genda T, Umemura T, Takehara T, Sakamoto N, Nishigaki Y, Nakane K, Toda N, Ide T, Yanase M, Hino K, Gao B, Garrison KL, Dvory-Sobol H, Ishizaki A, Omote M, Brainard D, Knox S, Symonds WT, McHutchison JG, Yatsuhashi H, Mizokami M. Sofosbuvir plus ribavirin in Japanese patients with chronic genotype 2 HCV infection: an open-label, phase 3 trial. J Viral Hepat. 2014;21:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Trivedi HD, Patwardhan VR, Malik R. Chronic hepatitis C infection - Noninvasive assessment of liver fibrosis in the era of direct acting antivirals. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, Zhu AX, Finn RS, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Heimbach JK. Diagnosis, Staging, and Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: 2018 Practice Guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2121] [Cited by in RCA: 3434] [Article Influence: 429.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 7. | Fujii H, Suzuki Y, Sawada K, Tatsuta M, Maeshiro T, Tobita H, Tsutsumi T, Akahane T, Hasebe C, Kawanaka M, Kessoku T, Eguchi Y, Syokita H, Nakajima A, Kamada T, Yoshiji H, Kawaguchi T, Sakugawa H, Morishita A, Masaki T, Ohmura T, Watanabe T, Kawada N, Yoda Y, Enomoto N, Ono M, Fuyama K, Okada K, Nishimoto N, Ito YM, Kamada Y, Takahashi H, Sumida Y; Japan Study Group of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (JSG-NAFLD). Prevalence and associated metabolic factors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the general population from 2014 to 2018 in Japan: A large-scale multicenter retrospective study. Hepatol Res. 2023;53:1059-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Enomoto M, Ikura Y, Tamori A, Kozuka R, Motoyama H, Kawamura E, Hagihara A, Fujii H, Uchida-Kobayashi S, Morikawa H, Murakami Y, Kawada N. Short-term histological evaluations after achieving a sustained virologic response to direct-acting antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:1391-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tobari M, Hashimoto E, Taniai M, Kodama K, Kogiso T, Tokushige K, Yamamoto M, Takayoshi N, Satoshi K, Tatsuo A. The characteristics and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease without cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:862-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 10. | Kawada N, Imanaka K, Kawaguchi T, Tamai C, Ishihara R, Matsunaga T, Gotoh K, Yamada T, Tomita Y. Hepatocellular carcinoma arising from non-cirrhotic nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1190-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peeraphatdit TB, Wang J, Odenwald MA, Hu S, Hart J, Charlton MR. Hepatotoxicity From Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review and Management Recommendation. Hepatology. 2020;72:315-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Remash D, Prince DS, McKenzie C, Strasser SI, Kao S, Liu K. Immune checkpoint inhibitor-related hepatotoxicity: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5376-5391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: Https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jiang X, China; Jiang W, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY